Lewis’s sculptures live in an argument that never ended. Who is allowed to represent freedom? Who gets to shape the “classical” tradition? What counts as American art—only what was produced inside the nation’s borders, or also what Americans made abroad because the nation wouldn’t make room?

Lewis’s sculptures live in an argument that never ended. Who is allowed to represent freedom? Who gets to shape the “classical” tradition? What counts as American art—only what was produced inside the nation’s borders, or also what Americans made abroad because the nation wouldn’t make room?

By KOLUMN Magazine

The first thing you learn about Edmonia Lewis is that much of what we want to know about her is contested—blurred by scarce records, by the selective gaze of 19th-century journalism, and by a long afterlife in which her story was retold in fragments, sometimes carelessly. Even her origins arrive with a haze: she was born in upstate New York, usually dated to 1844, and she described herself as of African and Native descent—often specified as Mississauga Ojibwe/Chippewa in museum biographies, with some sources emphasizing an Afro-Haitian connection through her father.

That ambiguity is not incidental. It is part of the point. Lewis’s life sits at the intersection of two American habits that shaped the 19th century and still shadow the present: the hunger to categorize people cleanly, and the refusal to accept what doesn’t fit the categories. In the years when the United States fought a civil war over slavery, then tried—haltingly, violently—to define citizenship in freedom’s wake, Lewis made a career in a medium that demanded money, training, patronage, and space. She chose marble, the material of empire and permanence, and used it to narrate subjects that American power routinely distorted: emancipation, Indigenous presence, Black humanity, and women’s interior life.

Her significance, then, isn’t only that she “made it” as a Black and Indigenous woman sculptor—though she did, and that alone would be historic. Her deeper significance is that she forced American art to reckon with a contradiction: a nation that claimed universal ideals while policing who could represent them. The fact that Lewis achieved international recognition in her lifetime and then became, for decades, a footnote—before a contemporary revival remade her into a symbol—tells us something unsettling about how cultural memory works, and whose genius is allowed to stay legible.

Childhood, kinship, and the making of “Wildfire”

Lewis’s early years are often described with the narrative shorthand reserved for exceptional figures: orphaned young, raised in her mother’s community, nicknamed “Wildfire.” The Smithsonian American Art Museum’s artist biography, echoed by other institutional sources, frames her upbringing as connected to her mother’s tribal life—fishing, swimming, crafts—before formal schooling pulled her into the world that would later reject her.

It’s worth pausing here because the “raised by the tribe” phrasing, repeated in many biographies, can flatten Indigenous life into a romantic prologue. What matters more is what that origin story does in Lewis’s career. Over and over, she would be read by patrons and critics as an emblem—“the Indian girl,” “the colored sculptress,” the exotic exception who proved a point for someone else. The problem Lewis spent her life solving was how to move from emblem to author: how to keep control of the meaning of her work in a culture that wanted her identity as a spectacle.

Her brother, Samuel, appears in many accounts as crucial to that early stability, financing her education and enabling her entry into institutions that did not open themselves easily to women or Black students. The Cantor Arts Center’s 2025–26 publication accompanying Edmonia Lewis: Indelible Impressions emphasizes the extent to which her migrations and professional life were documented in the press—and how networks of support, including family, helped make those movements possible.

Oberlin: A promise, then an accusation

In 1859, Lewis enrolled at Oberlin College, one of the rare American institutions then willing to admit women and Black students. The fact is cited so often that it risks becoming a feel-good line—proof that progress existed. But the real story of Oberlin, in Lewis’s life, is not progress. It is what happened when the promise of inclusion collided with the practice of prejudice.

In 1862, Lewis was accused by two white classmates of attempting to poison them. The case unfolded in a climate where rumor could operate as evidence and where a Black woman’s presence could be treated as a provocation. Accounts of the incident commonly note that charges were dismissed for lack of proof. Yet the legal outcome did not protect her from extralegal violence: she was assaulted—beaten severely—by white vigilantes, and her time at Oberlin became marked by isolation and further allegations.

The important detail is not simply that she was accused. It’s that the accusation functioned like a lever, prying her out of a space she had fought to enter. Later claims—about theft of supplies and involvement in a burglary—accumulated in ways that look, from a distance, like a social mechanism: a campus and town deciding what kind of person Lewis must be in order to justify pushing her out. The specifics remain contested across tellings, but the arc is clear: Oberlin did not allow her to finish on normal terms.

More than a century later, that institutional failure became part of her public afterlife. In 2022, Oberlin awarded Lewis a posthumous diploma, an unusual corrective that made news precisely because the original wrong had been allowed to stand for so long.

Boston: Abolitionist patronage and the business of likeness

Lewis arrived in Boston in the early 1860s and did what many artists without inherited wealth have done: she turned the market’s demands into a ladder. Portrait busts were a form of currency—objects that could be sold, replicated, and circulated among admirers. Lewis trained in the orbit of established sculptors and built relationships with abolitionist circles that were willing to support a Black artist whose work aligned with their politics.

The Washington Post’s account of her life emphasizes her resourcefulness in Rome—working without assistants, in part because she lacked the funds available to wealthier expatriate sculptors. That insistence on doing the carving herself mattered in a market that often suspected women artists, and especially artists of color, of being figureheads for someone else’s labor.

Lewis understood that suspicion and built her professional identity against it. One way she did so was by making the studio itself part of the story: visitors, journalists, and patrons came to see not only her finished marbles but the fact of her working—her hands on the stone. The Cantor publication describes how press coverage of her travels and studio attracted eminent visitors and helped her market neoclassical sculpture far from the traditional East Coast centers.

Rome: Exile as strategy, neoclassicism as leverage

By the mid-1860s, Lewis had moved to Rome, joining a community of expatriate women sculptors who found in Italy something America restricted: access to marble, to models, to a professional environment that—while hardly free of sexism—offered more room to work. The Peabody Essex Museum, which is mounting a major retrospective titled Edmonia Lewis: Said in Stone, places her Rome move in 1866 as a decisive step into the center of her generation’s sculptural world.

The choice of neoclassicism could look, at first glance, like assimilation: why adopt the aesthetic language of a tradition that was used to glorify whiteness and empire? Lewis’s answer seems to have been tactical. Neoclassicism was the credential. If she could master the style, she could force critics to discuss her on technical grounds, even if they wanted to reduce her to biography. The marble body—idealized, polished, “timeless”—was the Trojan horse that let her smuggle in contemporary meanings: emancipation, racial terror, Indigenous identity, women’s agency, religious suffering.

Rome also allowed her to insist on authorship. In an era when many sculptors relied on teams of assistants, Lewis’s practice—often described as unusually hands-on—became both a point of pride and a defense against doubt.

“Forever Free”: Emancipation, intimacy, and the politics of posture

If you want to understand Lewis’s ability to work inside conventions while quietly revising them, look at Forever Free (1867). In the sculpture, a Black man stands upright, one arm raised, a broken shackle visible; beside him, a Black woman kneels in prayer. It is a composition that has generated debate because it both rejects and reproduces the era’s visual hierarchies. The man stands—an important departure from the period’s frequent depiction of Black figures as perpetually kneeling or dependent—while the woman’s posture can read as a concession to Victorian ideals of piety and feminine submission.

Art historians have noted that the piece also performs a subtler intervention: it frames emancipation not only as legal status but as domestic possibility. Smarthistory’s analysis emphasizes the sculpture’s attention to intimacy and the newly legitimate recognition of enslaved people’s relationships and families—an argument embedded in the title itself, which insists on duration, not a temporary reprieve.

It is tempting to read Forever Free as “safe” abolitionist art—palatable to Northern patrons. But its restraint may be part of its strategy. Lewis was carving for a market that wanted moral uplift, yes, but also reassurance: emancipation as orderly progress. Within that demand, she preserved a radical claim. The man’s raised arm is not a gesture of gratitude to a white liberator; it is an assertion of self-possession. The chain is not held by another figure; it is broken. The center of the work is Black agency—carefully staged in a visual culture allergic to it.

Indigenous subjects: Refusing disappearance

Lewis’s work also engaged Indigenous themes, often through literary sources popular among white audiences, such as Longfellow’s The Song of Hiawatha. These pieces can be difficult to read today because they operate in a double register: they used mainstream texts that romanticized Native life, yet they also insisted, through craft and dignity, on Indigenous presence as something more than myth.

The PEM retrospective description notes that her stone sculptures “engage with Indigenous identity” alongside abolitionist and religious subjects, positioning her as an artist who moved among worlds rather than choosing a single, marketable label.

The complexity is the point. Lewis lived at a time when both Black freedom and Indigenous sovereignty were being negotiated through violence and law. Her sculptures did not solve those politics, but they refused a foundational American fantasy: that Indigenous people belonged only to the past.

Hagar: A biblical exile that looks like the modern world

Lewis’s Hagar (1875) is one of the clearest examples of her using a canonical story to speak about contemporary dispossession. Hagar, in the biblical narrative, is cast out into the wilderness. Lewis carves her standing, hands clasped, face lifted—an image of endurance at the edge of abandonment. The work is often described as neoclassical, but its emotional temperature is not cool. It is a figure in crisis, rendered with the calm surface marble demands.

PEM highlights Hagar as an anchor image for the forthcoming retrospective, signaling the museum’s view of the work as central rather than peripheral to American sculpture.

In a century saturated with debates about who belonged—who counted as citizen, woman, human—Lewis’s biblical women are not merely devotional. They are political allegories with plausible deniability. A patron could display Hagar as piety and still, if they allowed themselves to see it, confront a story about banishment and survival that mirrored the social realities of Black and Indigenous life in the United States.

The Death of Cleopatra: Realism, spectacle, and a century of misplacement

Lewis’s most famous work, and perhaps her most revealing, is The Death of Cleopatra (carved 1876), a monumental marble sculpture created for the Philadelphia Centennial Exposition. The Smithsonian American Art Museum describes the figure as Cleopatra “in the moment after her death,” still in royal attire, slumped on her throne; sphinxes flank the seat, and decorative hieroglyphics—more theatrical than accurate—signal “Egypt” to Western eyes.

What made the sculpture startling in its time was not simply the subject but the treatment. Rather than idealizing death into serene beauty, Lewis offered a body that looks heavy, unguarded, undeniably dead. Viewers had to confront mortality without the usual Victorian filters. The work created a stir, and it placed Lewis—briefly, forcefully—into the national conversation about American art.

Then the sculpture’s own life became a parable about neglect. The Washington Post reported in the 1990s on the sculpture’s rescue after “a century of neglect and abuse,” framing its recovery as both an art story and a story about the woman who made it.

Other accounts trace the sculpture’s bizarre journey through popular culture: removed from the art world, used as a marker for a racehorse’s grave, stored, damaged, and only later restored and brought to the Smithsonian. Smithsonian Magazine’s 1996 piece describes this long detour as a kind of American fable: masterpiece to curiosity to near-ruin to museum object again.

The sculpture’s fate is often told as misadventure. But it is also an indictment. Art does not “go missing” in a neutral way. Works are preserved when institutions and patrons decide they matter. Lewis’s Cleopatra survived because it was made of stone, because it was too large to disappear completely, and because later advocates—historians, local preservationists, curators—chose to look for it.

Fame without fortune, and the long eclipse

During her productive decades, Lewis achieved something rare: international recognition. Yet recognition did not guarantee stability. The Washington Post’s 2017 profile, written in the context of Google honoring her with a Doodle, emphasizes the precarity of her studio life and her decision to work without assistants. The subtext is clear: she was celebrated, but not buffered by the structures that protected many of her peers.

After 1907, she slipped into an archival fog. Basic facts—where she died, where she was buried—became uncertain for years, an extraordinary outcome for an artist whose work had once been national news. Later scholarship established that she died in London and was buried at St. Mary’s Catholic Cemetery.

In 2017, her story gained a literal marker: a campaign led by a local historian helped restore her grave, an act of civic memory that doubled as cultural critique. A grave should not be the only reliable proof that a person existed, but for Lewis, it became part of the evidence trail that modern admirers used to argue that she must be treated as a major American artist, not an anecdote.

Rediscovery as a mirror of the present

The revival of interest in Lewis is not accidental; it is historically timed. A culture newly willing to ask how race and gender shaped the archive has gone looking for the figures the archive minimized. In 2022, the U.S. Postal Service honored Lewis with a stamp in its Black Heritage series, holding the first-day ceremony at the Smithsonian American Art Museum—an institutional endorsement with symbolic weight.

That same year, Oberlin’s posthumous diploma became another public recognition, widely covered because it combined apology with belated celebration.

And now museums are building exhibitions that position Lewis not as a marginal “first,” but as a sculptor with formal ambition, commercial savvy, and intellectual range. The Peabody Essex Museum’s Edmonia Lewis: Said in Stone—described as the first major retrospective of its kind—explicitly frames her as a master of marble whose “true mastery” has been underrecognized.

The Cantor Arts Center’s 2025–26 exhibition, accompanied by essays from scholars including Tiya Miles, Gloria Bell, Kirsten Pai Buick, and Gwendolyn DuBois Shaw, similarly treats Lewis as an artist who prompts “new questions” about sculpture, portraiture, and “colored women artists” in the 19th century—language that signals a shift from inspirational biography to serious art-historical inquiry.

What these contemporary frames reveal is how the meaning of Lewis’s work changes depending on who is doing the viewing. In the 1870s, she could be praised as a curiosity: the “colored sculptress” who somehow mastered marble. In the 20th century, she could be neglected as an outlier who didn’t fit modernist narratives. In the 21st, she becomes something else: a diagnostic figure who shows the cost of exclusion in cultural institutions, and the power of craft as self-definition.

The question Lewis still poses to American art

Lewis’s sculptures live in an argument that never ended. Who is allowed to represent freedom? Who gets to shape the “classical” tradition? What counts as American art—only what was produced inside the nation’s borders, or also what Americans made abroad because the nation wouldn’t make room?

Lewis answered those questions without writing a manifesto. She answered with objects: stone bodies that insisted on dignity; a freedman standing; a queen dead in a posture too real to romanticize; a biblical exile carved with the patience of someone who understood banishment as more than metaphor.

Her life is often told as triumph over adversity. That is true, but it is also incomplete. The fuller truth is harsher and more useful. Lewis triumphed, and the culture still found ways to misplace her. The lesson is not only about her resilience; it is about the systems that required it—and about what changes when institutions finally decide that the work belongs at the center.

In KOLUMN’s language—culture as infrastructure—Edmonia Lewis is a blueprint for why the infrastructure matters. When the archive fails, genius becomes rumor. When the museum expands its frame, rumor becomes history again. The stone was always there. The looking had to catch up.

More great stories

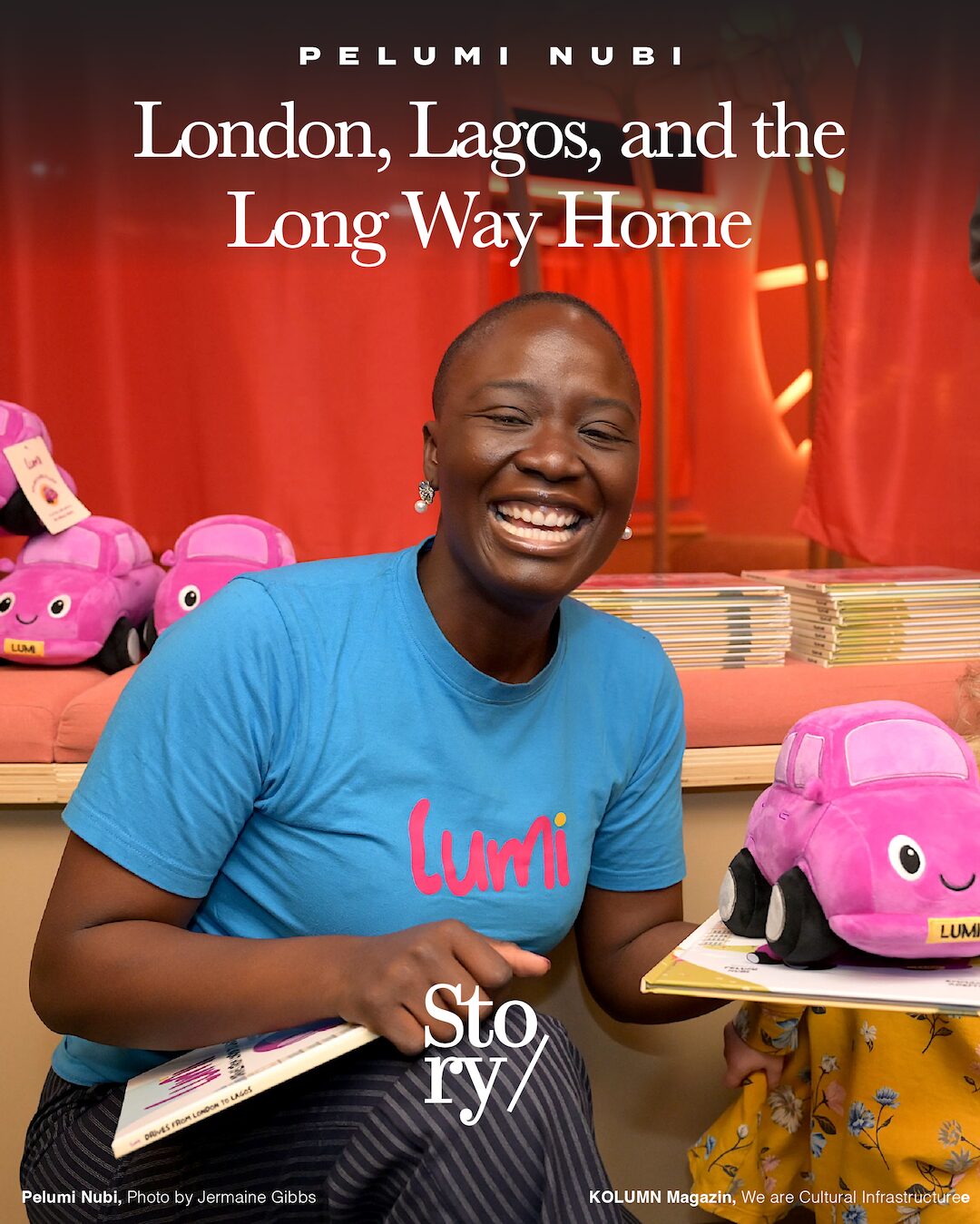

Pelumi Nubi: London, Lagos, and the Long Way Home