Bates was a reminder that civil rights is not a chapter but a practice, and that the practice requires people willing to do the unglamorous work of making bravery possible.

Bates was a reminder that civil rights is not a chapter but a practice, and that the practice requires people willing to do the unglamorous work of making bravery possible.

By KOLUMN Magazine

On certain mornings, history does not announce itself as history. It arrives as logistics.

A phone call. A change in plan. A teenager trying to keep her face still while a crowd swells outside a school that was never built for her to enter. A car that has to be in the right place at the right time. An adult who understands that “bravery” is not a personality trait but a system—made of safe houses, contingency routes, quiet instructions repeated until they sound ordinary enough to survive the day.

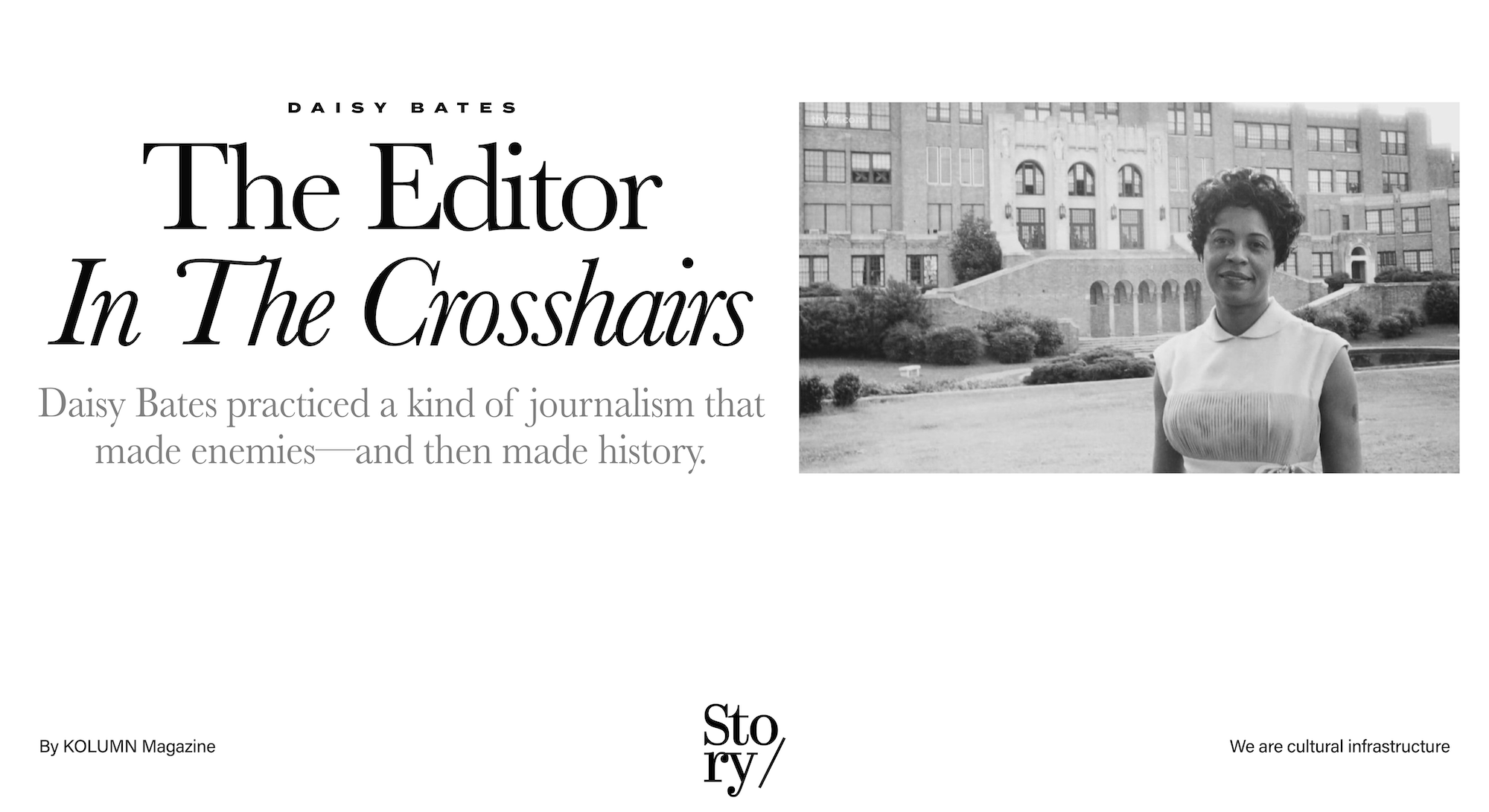

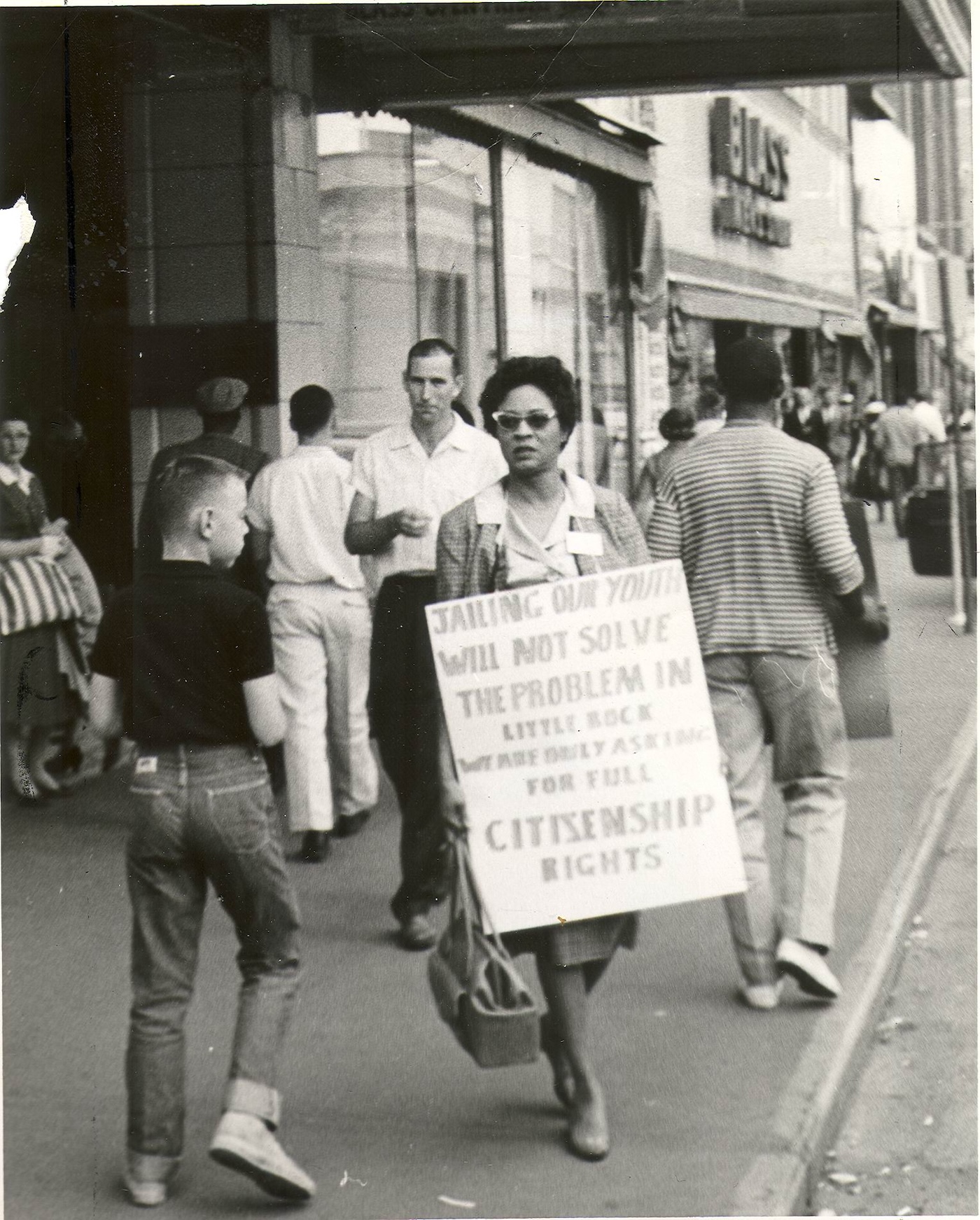

In Little Rock in September 1957, Daisy Lee Gatson Bates understood that system more intimately than almost anyone the nation would later praise. She is often introduced, correctly but insufficiently, as the Arkansas NAACP leader who advised and supported the Little Rock Nine. But Bates’ real significance sits deeper than the role titles we attach to civil-rights figures after the fact. She was a publisher who treated journalism as protection; an organizer who recognized that federal law meant little without local scaffolding; and a woman who helped transform a Supreme Court decision into lived experience—one school day at a time.

The story Americans remember is a clash of icons: Orval Faubus, Dwight Eisenhower, the 101st Airborne, and a mob at Central High. The story Americans often forget is how that clash became legible to the world: because a Black press institution in Arkansas kept documenting the state’s evasions, and because a civil-rights organizer in Little Rock made a battlefield out of procedure—meetings, calls, affidavits, rides, and a home that became, as the National Park Service now describes it, the de facto command post of the crisis.

Bates’ life forces a harder question than the one school desegregation narratives usually ask. The easy question is, “Who was against integration, and who was for it?” The harder question is, “What did it take to make the promise of citizenship survivable?” Daisy Bates, more than most, answers that harder question—not as philosophy, but as method.

A childhood formed by violence—and by the decision to look straight at it

Daisy Bates was born Daisy Lee Gatson in Huttig, Arkansas, in the early 1910s; many standard biographies cite November 11, 1914, though archival descriptions sometimes note uncertainty around the exact year. That ambiguity is not unusual for Black Southerners born in an era when recordkeeping could be casual for white families and cruelly inconsistent for everyone else. What is not ambiguous is the violence that framed her childhood. Accounts preserved in public-history summaries describe Bates’ mother as having been killed after resisting a sexual assault, and Bates being raised by adoptive parents after her father left.

The detail is almost unbearable, and that is precisely why it matters: Daisy Bates’ later insistence on telling the truth about Arkansas was not a sudden conversion in middle age. It was a lifelong refusal to treat racial violence as rumor, as private tragedy, or as the price of Southern order. Her activism did not begin with a national spotlight; it began with the lived recognition that what happened to Black women in the South could be erased twice—first by the act itself, then by silence.

When historians talk about civil-rights leadership, they often emphasize charisma or oratorical gift. Bates’ gift was different. She possessed what might be called a moral administrative intelligence: an ability to organize human risk into something that could be managed, contested, and recorded. That ability is not accidental. People who grow up amid terror often develop either the impulse to hide or the impulse to map. Bates mapped.

The Arkansas State Press: Advocacy journalism as a strategy, not a genre

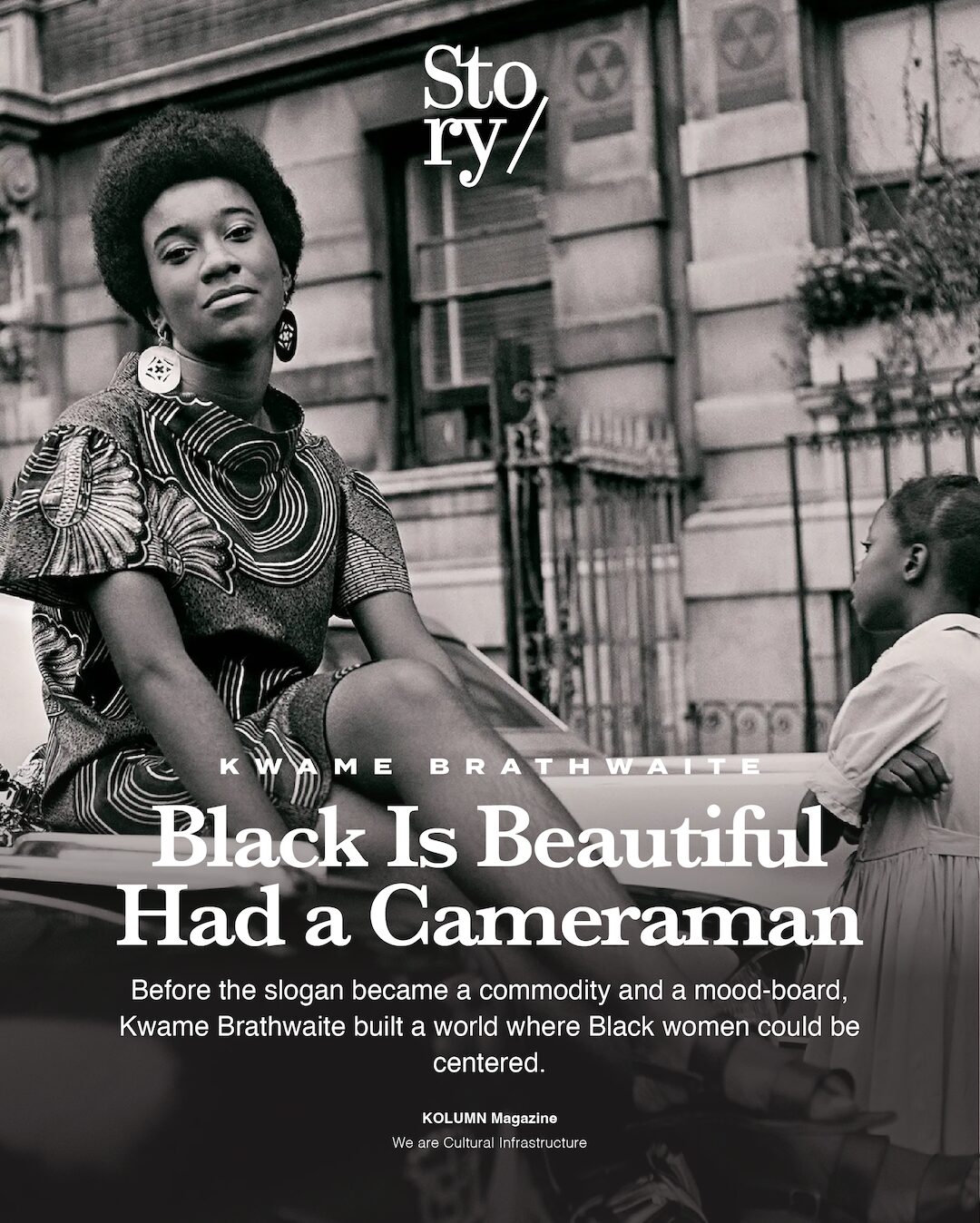

If Daisy Bates is a civil-rights figure, she is also a journalism figure—one whose career complicates the American myth that “objective” reporting sits apart from political struggle. In 1941, she and her husband, L. C. Bates, founded the Arkansas State Press, a Black weekly that became a central institution in Little Rock’s Black community and a persistent irritant to segregation’s local managers.

The Library of Congress entry on the paper describes it plainly: a local newspaper started in 1941 by a Black civil-rights activist couple, later famous for its coverage during the Central High desegregation crisis. The University of Arkansas special collections guide places the paper’s significance in the long arc of civil-rights advocacy in the state, noting its influence and its direct confrontation with legal and political inequities.

This is the first major theme of Bates’ life: she treated information as power, and she built an institution to produce and distribute it.

The Black press has often been described as the movement’s “backbone,” but that phrasing can romanticize the work into metaphor. The Arkansas State Press was not a symbol; it was a mechanism. It created public memory inside a place determined to deny that memory existed. It named discrimination that local white papers might euphemize, ignore, or justify. It circulated achievements of Black Arkansans in a state whose public culture worked to make Black accomplishment seem like exception rather than community norm.

It also exacted a cost. In Little Rock, to publish civil-rights journalism was to invite retaliation not only from extremists but from the respectable middle of white civic life—advertisers, local officials, business owners who could punish without ever joining a mob. Accounts of the period note how financial pressure, including the withdrawal of advertising, helped force the paper to shut down by the end of the 1950s. That pattern—economic punishment as political discipline—was one of segregation’s most reliable tools, and Bates learned early that the fight was not only in courtrooms and schoolhouses but also in the quiet systems that make institutions viable.

It is worth underlining, especially for modern readers, how contemporary this tactic feels. When a community punishes a journalist not with censorship law but with market pressure, it can pretend it is merely “business.” Bates’ career refuses that pretense.

The NAACP in Arkansas: When membership itself is a risk

By the time Little Rock’s school crisis exploded into national headlines, Daisy Bates was already deeply embedded in the NAACP’s local and state organizing. She served as president of the Arkansas NAACP, a position that in the Jim Crow South could make a person a target simply by existing in public.

KOLUMN Magazine’s own historical analysis of the NAACP frames the organization’s founding as a response to racial terror and to a national press culture capable of laundering that terror into “disorder” or justification. That framing is not just background; it is the world Bates inhabited. In Arkansas, the NAACP’s presence signaled litigation, federal pressure, and the disruption of local white control. In many Southern cities and towns, officials treated the NAACP less as a civic association than as an enemy agency.

Bates understood that the struggle was not only over desegregation but over the right to organize at all. That insight would later reach the Supreme Court in a form that now reads like constitutional doctrine but began as personal danger.

In Bates v. City of Little Rock (1960), the Supreme Court ruled that compelled disclosure of NAACP membership lists, on the record presented, would unjustifiably interfere with freedom of association. The case matters beyond legal trivia because it reveals segregation’s playbook: if you cannot defeat civil-rights organizing through open bans, you can defeat it by exposure—by forcing names into public view in a context where harassment and threats are predictable consequences. Congressional constitutional commentary later summarized the evidentiary point bluntly: publicly identified members had faced harassment and threats of bodily harm.

This is the second theme of Bates’ life: she fought not only for integrated schools but for the protective privacy that makes democratic participation possible. In an era when “doxxing” is a modern word for an old practice, Bates’ story reads as warning and precedent.

Choosing the nine: Why the Little Rock crisis was not spontaneous

The Little Rock Nine are remembered as brave teenagers—and they were. But their bravery did not appear out of thin air, and it was not simply an individual decision to “be strong.” It was a planned NAACP strategy to test Brown v. Board of Education in a local context where resistance was expected.

Bates’ role in that strategy was both practical and intimate. Public-history accounts emphasize her guidance and her position as a coordinator for the students. The National Park Service, describing the Bates home, notes that it served as a haven for the students and a place to plan “the best way to achieve their goals.”

The word “haven” can sound soft. In 1957 Little Rock, a haven was a tactical asset.

To understand why, it helps to recall what “Massive Resistance” looked like on the ground. KOLUMN Magazine’s reporting on Prince Edward County’s school closures after Brown—public schools shut down rather than integrate—captures the underlying logic: when forced to choose between public education and racial hierarchy, segregationist leadership often chose hierarchy. KOLUMN’s examination of segregation academies as a durable post-Brown architecture similarly shows how resistance did not always scream; it reorganized.

Little Rock’s resistance would scream. But it also reorganized—through local police posture, state National Guard deployment, and municipal harassment aimed at the NAACP.

Bates prepared for a world in which the law’s words could be true in Washington and false in Arkansas. Her job was to close that distance.

September 1957: When procedure becomes survival

The images that endure from Little Rock are cinematic: a mob at the school, federal troops, students walking into Central High beneath national attention. But Bates’ work was less cinematic and more relentless. She arranged transportation, coordinated communications, and served as a buffer between children and a city’s fury. Her home, now recognized as historically significant, became a hub for daily operations and a target for segregationist violence.

One of the most discussed moments of that first week—the image of Elizabeth Eckford walking alone into a hostile crowd—has also been tied, in later retellings, to communication failures among adults trying to manage chaos. Even sympathetic accounts note Bates’ later regret about not ensuring that Eckford received an updated plan. That detail matters because it humanizes Bates without diminishing her. It shows the impossible standard organizers were held to: perfection in a situation engineered for panic.

In mainstream civic mythology, crises are resolved by leaders in suits. Little Rock was resolved, in part, by a woman doing organizer math under threat: how to get nine children into a building, how to keep them alive, how to keep an organization functioning while the state tries to intimidate it into nonexistence.

This is also where Bates’ identity as a journalist sharpened her organizing. She knew that the story being told about Little Rock would shape what the federal government felt pressured to do. KOLUMN Magazine’s longform work on other civil-rights-era flashpoints has highlighted how international perception often mattered—the Cold War context in which American racism became, repeatedly, a foreign policy liability. In KOLUMN’s recent analysis of the “Kissing Case,” the piece explicitly invokes federal anxieties that show up “from the federal government’s anxieties about Little Rock” onward.

Bates understood that shame is a political resource. She helped produce it.

The federal state and the local state: What Little Rock exposed

The Little Rock crisis is often summarized as a dramatic test of Brown and of federal authority. That is true, but it is also incomplete. The deeper test was whether a constitutional right could be enforced when a state government mobilized its resources against it.

History.com’s overview of the episode describes the Little Rock Nine’s enrollment as a direct test of Brown and notes the intensity of opposition that required federal intervention. Washington Post archival reporting, in later years, recounted the violence of the mob and the role Daisy and L. C. Bates played in organizing the students.

When Eisenhower sent federal troops, it was not simply a moral gesture. It was an acknowledgment that the local state had aligned itself with obstruction—and that national power would be used to force compliance. The famous line about how many soldiers it took to ensure nine children their rights appears in a National Park Service brochure focused on Bates, capturing the bitter arithmetic of American democracy when it is challenged by race.

Bates’ significance here is not merely that she was present. It is that she helped create the conditions in which the federal government could not plausibly look away. She did this through organizing and through publication—through the dual pressure of the street-level movement and the narrative record.

Retaliation after the cameras: Harassment as governance

Segregationist regimes rarely end when a single crisis is “resolved.” They adapt.

In Little Rock, one form of adaptation was legal harassment aimed at the NAACP and its leadership. This is where Bates’ name enters constitutional history. Bates v. City of Little Rock did not arise because city officials suddenly became interested in bureaucratic compliance; it arose because disclosure requirements could be weaponized to weaken civil-rights infrastructure.

The Supreme Court’s holding is now taught as part of a broader freedom-of-association doctrine, alongside other NAACP cases. But what those holdings conceal, if you read them only as doctrine, is the human reality underneath: organizers and members facing harassment and threats if their names became public.

This is the third theme of Bates’ life: she illustrates how “law” can be used both as liberation and as intimidation, sometimes by the same government system. She lived in the seam between those uses and forced the seam open.

Writing the memoir: “The Long Shadow of Little Rock” as counter-archive

After the crisis years, Bates wrote what may be her most direct act of historical preservation: her memoir, The Long Shadow of Little Rock. The book first appeared in the early 1960s and would later be republished and honored decades after its initial release.

Memoir, in civil-rights history, is often dismissed as “personal.” Bates’ memoir is better understood as counter-archive—an attempt to fix into narrative what official Arkansas would prefer to forget or distort. The University of Arkansas special collections include extensive Bates materials, and exhibits built from those collections underscore the documentary richness of her papers and her continuing historical relevance.

In one sense, the memoir is a continuation of the Arkansas State Press by other means. Where the paper documented a living struggle in real time, the memoir documents the struggle’s meaning—how it felt, how it was organized, how it was resisted, and how it cost.

The stakes here are not literary. They are civic. When communities fight over “what happened,” they are often fighting over what obligations the present inherits.

The life beyond Little Rock: Politics, anti-poverty work, and rural Black community building

A common failure in civil-rights storytelling is to freeze people at their most famous moment—as if their lives existed to produce one photograph.

Bates’ later years resist that freezing. Accounts note her move to Washington, D.C., work connected to the Democratic National Committee, and involvement in anti-poverty programs during the Johnson era. After health challenges, she returned to Arkansas and later focused energy on community development in Mitchellville, a rural Black community where she supported self-help initiatives tied to basic infrastructure improvements.

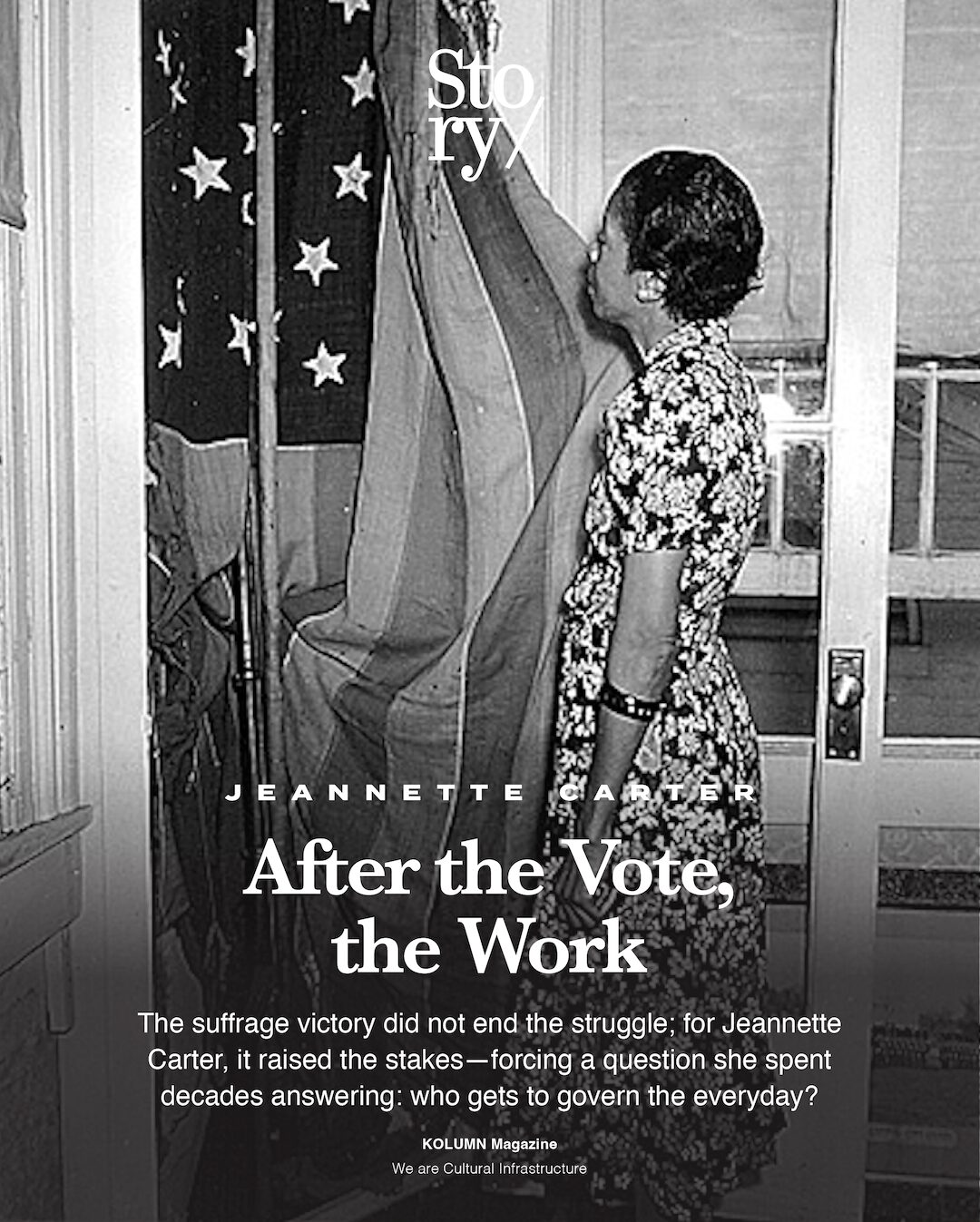

This arc matters because it complicates the idea that civil rights is only about symbolic integration. Bates’ post–Little Rock work speaks to a broader understanding: that rights without resources can become hollow, and that democracy is partly measured in whether people have functioning systems—water, streets, community centers—that let them live with dignity.

In a different register, it also suggests something psychologically true about organizers: after surviving a national crisis, some return to the quieter work that crises often eclipse. Not every victory comes with troops and headlines. Some come with paved streets.

Recognition, memorialization, and the politics of who gets remembered

The honors Bates received reflect both her immediate impact and the country’s slow-moving willingness to acknowledge that impact. She and the Little Rock Nine received the NAACP’s Spingarn Medal in the late 1950s, and her later memoir would receive renewed recognition decades later. Her home became a National Historic Landmark, formalizing what movement participants already knew: the living room matters.

The modern memorialization of Bates has also taken a particularly visible form. In 2019, Arkansas moved to replace one of its National Statuary Hall figures with Bates, and in May 2024 her statue was unveiled at the U.S. Capitol—an act framed, in contemporary reporting, as part of a broader reassessment of whom states choose to honor. (Reuters) Reuters described the statue’s symbolism—Bates depicted with a newspaper, notebook, and pen—emphasizing the fusion of her activism and journalism.

Word In Black’s coverage of the statue likewise foregrounded Bates as a Little Rock Nine activist being honored in the Capitol, tying her recognition to the politics of representation and replacement. AP reporting added detail on the sculptor’s research process, including attention to Bates’ autobiography and to her Little Rock sites, underscoring how memorialization can also operate as an invitation to study.

Even this, however, is not simple celebration. Memorials can domesticate radicalism; they can turn a person who disrupted power into a person who merely “inspired.” Bates’ story pushes against that softening, because her accomplishments were not abstract.

She forced a state to confront federal law. She helped protect children under threat. She defended associational privacy in a landmark Supreme Court case. She built a newspaper that refused to treat discrimination as a local custom.

These are not vibes. They are interventions.

Daisy Bates as a theory of change: What her life teaches about movements

If you treat Daisy Bates as a single role—mentor of the Little Rock Nine—you miss her larger contribution. Her life offers a blueprint for how movements become effective.

First, Bates shows the necessity of institutions. The Arkansas State Press functioned as a civic organ, not merely a business. Movements that rely only on mass emotion tend to burn out or be crushed. Movements that build institutions can outlast a season of repression.

Second, she shows the importance of legal literacy paired with local strategy. Brown did not integrate Central High by itself. It took NAACP planning, community recruitment, and daily coordination. Bates lived at the junction of doctrine and street-level reality.

Third, she shows how power retaliates: not only through mobs but through paperwork. The membership-list fight that culminated in Bates v. Little Rock reveals a form of repression that can look administrative and still function as terror.

Fourth—and this is where Bates intersects with journalism ethics—she demonstrates that documenting injustice is not a neutral act, but it is an essential one. The ethical standard is not detachment. The ethical standard is truthfulness, rigor, and fairness about what is happening and who is doing it. Bates’ career argues that “advocacy journalism,” when grounded in facts and accountable narrative, can be a form of democratic defense.

KOLUMN Magazine’s own civil-rights and institutional-history reporting repeatedly returns to this point: the struggle is rarely only about a single law or a single moment. Whether tracing Massive Resistance through school closures or mapping the long tail of segregation academies or situating NAACP work as a response to racial terror and media distortion, KOLUMN’s lens is structural. Daisy Bates belongs in that structural tradition. She did not merely stand in history’s spotlight; she helped build the wiring behind it.

What gets lost when Daisy Bates is treated as a supporting character

There is a reason Bates can be misremembered as “part of the Nine”—a mistake so common that The Guardian has even issued a clarification noting that she was not one of the Little Rock Nine but rather an activist who supported them. The mistake reveals a cultural habit: we compress complex movement ecosystems into a handful of easily named heroes, and we flatten organizers into background.

But Bates’ story insists that the “background” is where the work happens.

A teenager walking through a mob is a scene. A woman arranging the conditions for that walk, day after day, is a system. Americans are trained to honor scenes. Democracies survive because someone builds systems.

Bates was also a Black woman operating within a movement world that could both rely on and marginalize women’s labor. Gendered histories of civil rights have long noted how women often served as strategists, fundraisers, administrators, and protectors while public leadership roles skewed male. Bates’ prominence complicates that pattern, but it does not erase the pressures around it. To lead publicly as a woman in 1950s Arkansas was to invite particular forms of dismissal and threat.

Her response was not to request permission. It was to proceed.

A closing image: The notebook, the newspaper, the living room

When Arkansas chose Daisy Bates as one of its representatives in the U.S. Capitol’s National Statuary Hall, the sculptural symbolism leaned into what made her distinctive: a notebook, a pen, a newspaper—tools of record and persuasion rather than weapons in the literal sense. The choice is apt because Bates’ power was always rooted in tools that democratic societies claim to value: speech, press, association, petition.

And yet, her life also exposes how fragile those values become when they threaten hierarchy. Little Rock required soldiers to enforce school integration. Arkansas tried to cripple civil-rights organizing by demanding membership lists. A newspaper that told the truth could be economically strangled.

Daisy Bates’ achievement is that she did not treat those contradictions as evidence that democracy was a lie. She treated them as evidence that democracy was unfinished—and that finishing it required infrastructure: institutions that could coordinate risk, preserve truth, and outlast intimidation.

In the end, perhaps the most honest way to describe Daisy Bates is not as a single kind of figure. She was a publisher-organizer-constitutional-plaintiff-community-builder. She was a reminder that civil rights is not a chapter but a practice, and that the practice requires people willing to do the unglamorous work of making bravery possible.

The Little Rock Nine needed courage. They also needed a headquarters.

They had Daisy Bates.

More great stories

The Case of Alberta Jones