Davis is arguing that the very categories through which politics is organized determine who will be protected, who will be blamed, and who will be asked—yet again—to wait.

Davis is arguing that the very categories through which politics is organized determine who will be protected, who will be blamed, and who will be asked—yet again—to wait.

By KOLUMN Magazine

Women, Race, & Class is one of those works whose first and most radical move is not a thesis, but a correction. The correction is simple enough to sound like common sense—and complicated enough to keep landing like an accusation: you cannot talk honestly about women in the United States without talking about race, and you cannot talk honestly about either without talking about class. Angela Y. Davis published the book in 1981, as a set of essays that reads like a guided tour through America’s political mythology: the “pure” moral clarity of abolition, the triumphant inevitability of women’s suffrage, the supposedly universal “woman’s” experience invoked by second-wave feminism, and the familiar promise that rights—once granted—will trickle down. Davis doesn’t merely critique these narratives. She rewrites their cast list and changes the lighting, showing who is centered, who is made peripheral, and who is erased altogether.

From the beginning, Davis’s intervention is historical, but it is never antiquarian. She is not collecting names for a hall of fame. She is tracing structures: how slavery and industrial capitalism shaped gendered labor; how “respectable” womanhood was manufactured as a racial project; how the vote, framed as a universal feminist milestone, was often argued for in explicitly racist terms; how the sexual terror of lynching-era America relied on myths that made Black men into monsters and Black women into silence. The book is thick with detail—court records, speeches, organizational debates, policy fights—but its ambition is ultimately moral and strategic. It asks what coalition is possible when the reality of women’s lives is not flattened to fit the most socially protected among them.

It is hard now to remember how much American public language once depended on cleaner boundaries. “Race” in one box. “Women” in another. “Workers” somewhere else. In 1981, Davis’s insistence that these are not separate struggles—and that any politics built on treating them as separable would reproduce inequality—pushed against not only mainstream feminism but also parts of the left that spoke class fluently while treating gender and sexuality as secondary matters. A later academic vocabulary would name what Davis was doing “integrative” analysis or, more popularly, “intersectional” thinking, though Davis’s work is not reducible to a term that arrived afterward. Her point is not that identities overlap like a diagram. Her point is that power arranges society through overlapping logics—and that movements fail when they misdiagnose the architecture.

The fact that the book still circulates so widely—assigned in universities, passed hand-to-hand in organizing spaces, referenced in debates about reproductive justice, labor, and carceral politics—says something about how slowly American institutions change, and how quickly movements forget their own internal exclusions. Penguin Random House’s description of the book, aimed at general readers, emphasizes exactly the issues that make the essays feel contemporary: rape, reproductive freedom, housework, and child care, all refracted through the inequalities between Black and white women. But Davis is doing something more fundamental than topical relevance. She is arguing that the very categories through which politics is organized determine who will be protected, who will be blamed, and who will be asked—yet again—to wait.

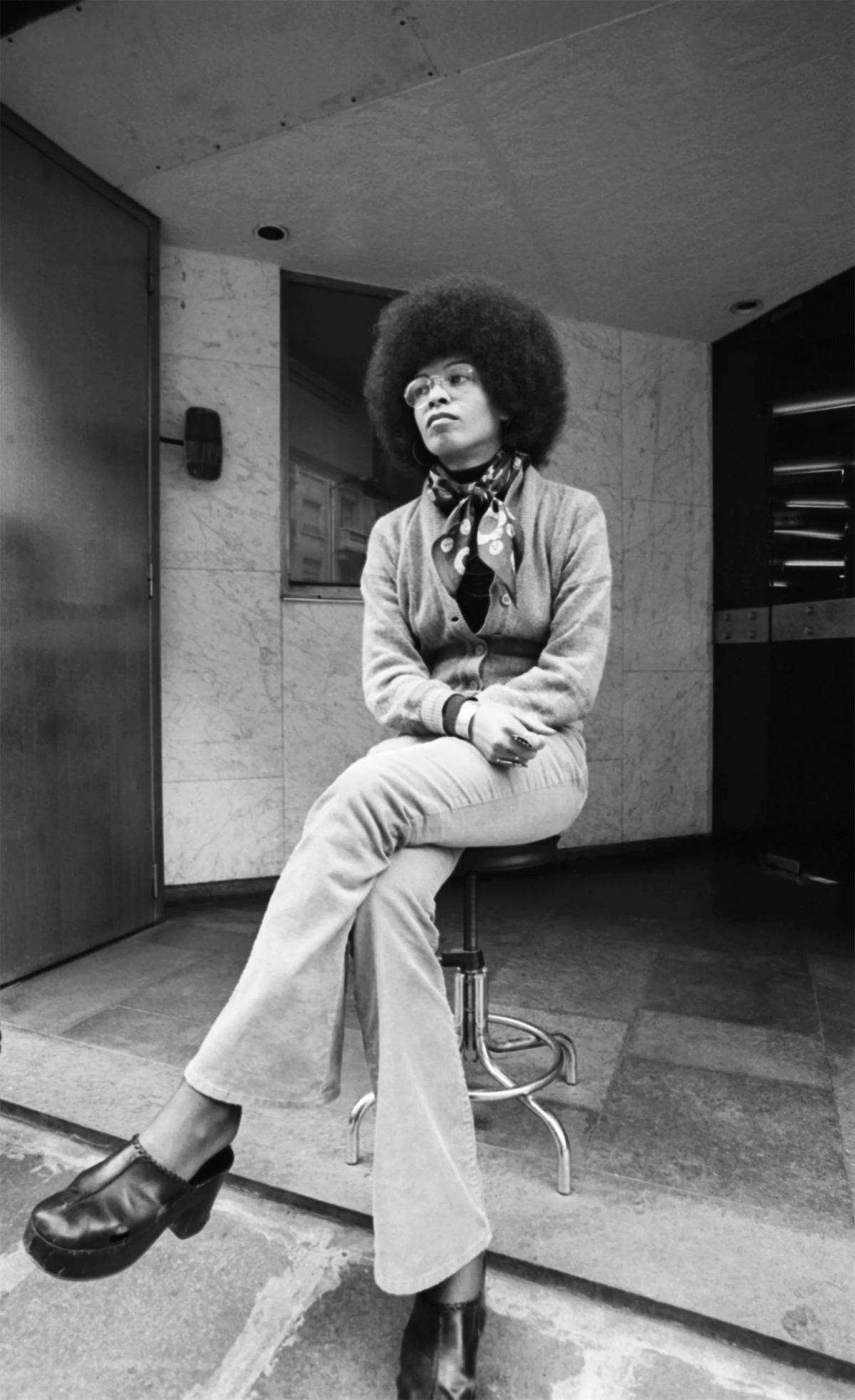

To understand why Women, Race, & Class lands the way it does, you have to understand the person writing it: not as iconography—the afro, the clenched fist, the FBI poster—but as a political intellectual formed by specific places, organizations, and historical shocks. The book is not a detached academic exercise. It is the work of someone who had already been made into a symbol by the state and by a global movement, someone who had watched “law and order” manufacture enemies, and someone who had learned—through harsh publicity—that coalition is not only an ethical aspiration but a survival strategy.

“Dynamite Hill” and the education of a radical

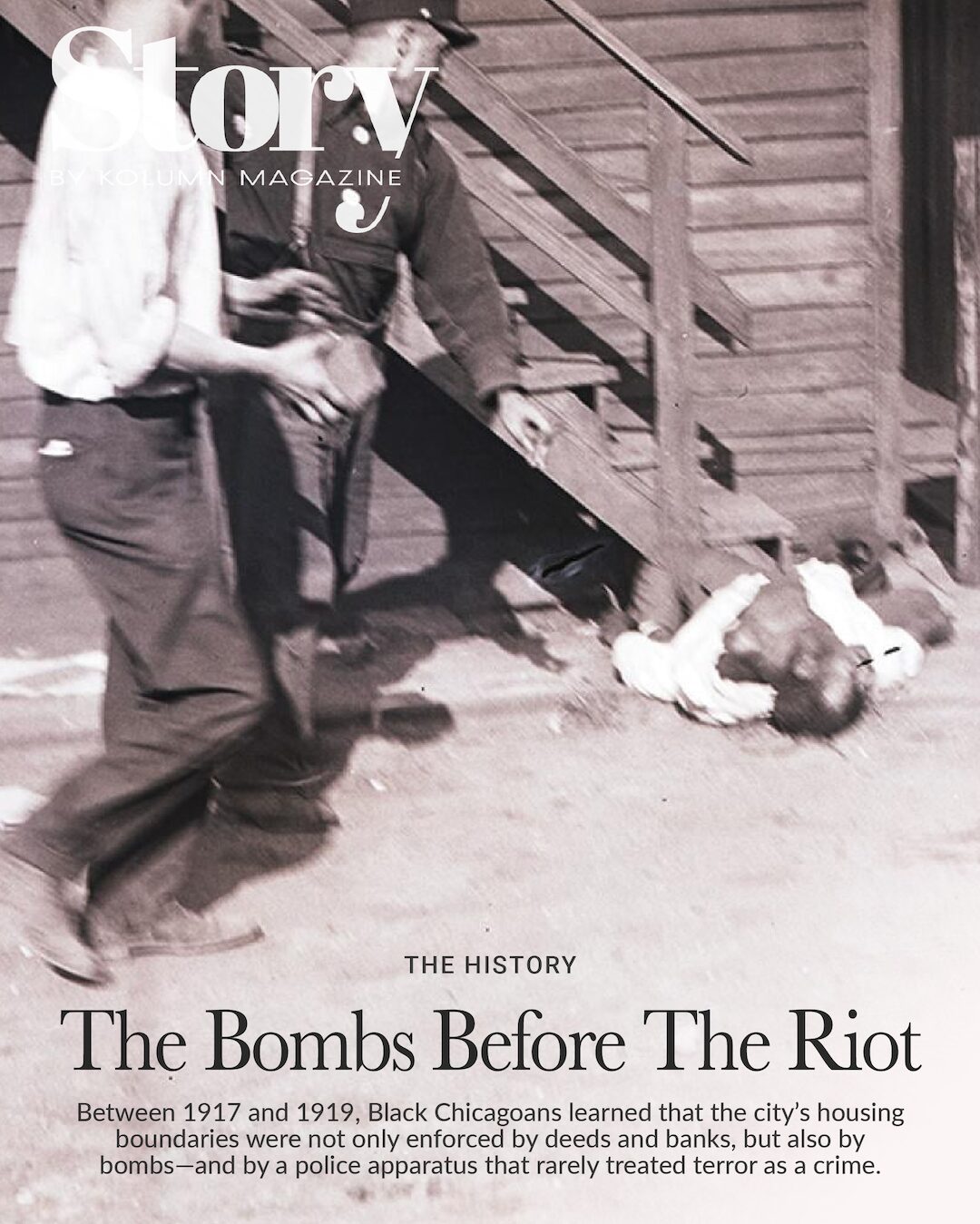

Angela Davis was born in 1944 in Birmingham, Alabama, and grew up in a neighborhood that would be known for racist violence and intimidation, a landscape where bombings were not metaphor but method. The neighborhood’s nickname—“Dynamite Hill”—was not a flourish. It reflected how white supremacist terror worked to police Black mobility and Black aspiration, targeting families who moved into areas marked as forbidden.

Biography can easily become a straight line in retrospect: the child in segregated Birmingham grows up to critique American racism. But Davis’s formation matters in its specificity. She grew up around political organizers and debates about strategy and ideology; her mother had ties to left organizing traditions in the South, and Davis would later describe being shaped by a milieu in which capitalism and racism were not treated as separate problems. When she left Birmingham—first through educational opportunities that placed Southern Black students in integrated schools in the North—she gained not only access but contrast: a living demonstration that segregation was not the natural order but an enforced one, and that the United States could present itself as democratic while running daily apartheid at home.

Davis’s formal education often gets summarized as a list of elite institutions—Brandeis, Frankfurt, UC San Diego, UCLA—but it is more revealing to track the ideas and tensions that came with those settings. At Brandeis, she encountered Herbert Marcuse, the Frankfurt School philosopher who modeled a kind of intellectual life in which scholarship and political commitment were not enemies. Davis later credited Marcuse with demonstrating that one could be an academic and a revolutionary at once—a template that would become central to her public identity.

Her time in Europe deepened her engagement with Marxist thought, not as a slogan but as an analytic framework for reading capitalism’s social arrangements. She would return to the United States in the late 1960s not as a graduate student trying to find a topic, but as someone convinced that theory belonged in the street and the courtroom as much as in the seminar room. She joined organizations that would define her in the public imagination—the Communist Party USA and, for a period, the Black Panther Party—while also becoming involved in feminist politics and antiwar activism.

This is one of the underlying dramas of Davis’s life: she was formed in a moment when American political possibilities seemed both urgently expansive and brutally constrained. The late 1960s and early 1970s were years of mass mobilization and state crackdown; of revolutionary rhetoric and COINTELPRO surveillance; of utopian organizing experiments and prison cells. Davis would become, in the most literal way, a figure through whom the state tried to make an example.

The making of a “dangerous” woman

In 1969, Davis was hired as an assistant professor of philosophy at UCLA, a prestigious post that should have been the beginning of a conventional academic career. Instead, it became a public spectacle. The university’s governing board moved to fire her because of her Communist Party membership. The dispute turned into a flashpoint about academic freedom, Cold War loyalty tests, and the boundaries of permissible dissent. A court ruling initially forced her reinstatement, but the university later dismissed her again, citing “inflammatory” speech.

If this sounds like institutional bureaucracy, it was also a form of political theater: a warning that certain ideas were not simply wrong but disqualifying. Davis’s politics made her legible to a nervous American establishment as a kind of threat: not only Black, not only radical, but intellectually rigorous and publicly articulate—a combination that historically triggers repression.

The event that pushed her from controversial professor to international cause célèbre came in 1970. Guns registered to Davis were used in an armed takeover of a courtroom in Marin County, California, an attempt connected to the case of the “Soledad Brothers,” imprisoned men whose treatment had drawn activist attention. The incident resulted in multiple deaths, including a judge. Davis was charged with serious felonies and spent more than a year in jail before being acquitted in 1972.

The legal facts—ownership of weapons, the prosecution’s theory of conspiracy, the jury’s verdict—matter, but so does the political meaning. Davis’s case became a global referendum on the U.S. justice system’s willingness to criminalize radicalism. A campaign for her release mobilized across countries and movements, turning “Free Angela” into a slogan that linked civil rights, anti-imperialism, and feminist organizing. The Guardian’s later profile notes how Davis herself frames the global campaign as proof of collective power, and how her imprisonment shaped her lifelong commitment to abolitionist politics.

By the time Davis wrote Women, Race, & Class, she was not merely reflecting on history from an academic distance. She had lived the state’s readiness to treat political association as criminal intent. She had watched how media narratives flatten a person into an emblem. And she had experienced solidarity as something built—painstakingly—across difference.

That lived knowledge shows up in her book’s orientation. Davis is suspicious of purity. She does not write as if any movement is automatically righteous. She shows how abolitionists could be heroic and racist, how suffragists could be visionary and white supremacist, how feminists could speak the language of liberation while organizing around the interests of women who already had social protection. The history she offers is not comforting. It is usable.

What Women, Race, & Class actually does on the page

It is easy to describe the book as “about intersectionality” and leave it there, as if Davis simply anticipated a later scholarly framework. But the book is more specific, and more abrasive, than that gloss suggests. Structurally, it is a set of essays that move through U.S. history from slavery and abolition to suffrage, labor struggles, and the women’s liberation movement, repeatedly showing how movements that claimed universality often depended on exclusions.

Davis begins from slavery not because she is writing an origin story, but because slavery is the foundational American institution in which race, gender, and labor were engineered together. Under slavery, Black women were forced into labor regimes that did not match the dominant white ideal of femininity. The enslaved woman was made to work like a man in the fields while also being expected to perform domestic labor; her reproductive capacity was exploited as economic production; her sexual vulnerability was not an aberration but a feature of the system. Davis’s insistence on these realities is also an argument against later romanticizations of womanhood. If “woman” is defined through fragility and domestic purity, then enslaved women appear as exceptions—or as not fully women at all. Davis refuses that framework.

From that starting point, Davis traces how abolitionist politics and early feminist politics intertwined and diverged. She shows white women abolitionists entering public life through antislavery work and developing political skills—speaking, organizing, writing—that would later shape demands for women’s rights. But she also documents how racial hierarchies persisted within reform movements, and how the post–Civil War period produced bitter fights over whether Black men’s suffrage should come before women’s suffrage, fights in which some prominent suffragists deployed explicitly racist arguments. Davis’s point is not to cancel historical actors but to expose how racism was not incidental; it shaped strategy, rhetoric, and organizational priorities.

Then there is labor. Here Davis’s Marxist feminism becomes especially clear. She treats the household not as a private refuge but as a political economy, a site where women’s unpaid labor subsidizes capitalism. In the chapter often excerpted and circulated separately, “The Approaching Obsolescence of Housework,” Davis argues from a working-class perspective about how domestic labor has been organized, who is paid to do it, and what it would mean to “socialize” housework rather than treat it as women’s natural destiny.

This is where Women, Race, & Class cuts against mainstream feminist narratives that center the suburban housewife’s confinement as the paradigmatic women’s problem. Davis does not deny that confinement. She contextualizes it—and reminds readers that Black women, because of the labor market’s racial ordering, have often worked outside the home in large numbers, frequently doing paid domestic labor in white households. That reality scrambles simplistic stories about liberation being identical with wage work, because wage work itself is stratified and exploitative. Davis is relentlessly attentive to who gets hired, who gets underpaid, and who is asked to raise someone else’s children to feed their own.

The book’s chapters on sexual violence and reproductive politics are equally unsparing. Davis frames rape not as a miscommunication or a private moral failure but as an exercise of power, historically racialized in the United States. She examines how white men’s sexual access to enslaved women was normalized, while the myth of the Black male rapist was weaponized to justify lynching and social control. She also critiques how anti-Black racism shaped the politics of birth control and sterilization, insisting that reproductive freedom cannot be reduced to an abstract “choice” when structural coercion and medical abuse have targeted women of color.

A contemporary essay in the Boston Review makes a related point in modern terms, arguing—through Davis’s lens—that abortion cannot be treated as “choice” without racial justice, precisely because access and coercion have never been evenly distributed. The endurance of this argument is part of the book’s significance: Davis provides a history that explains why later “reproductive justice” frameworks emerged, and why single-issue politics around reproduction so often fail the people most affected.

Throughout, Davis’s tone is not that of a neutral chronicler. She writes as someone who believes history has consequences. She is not simply describing how feminism excluded women of color; she is warning that movements that repeat this pattern will reproduce domination under a new brand.

The author as method: How Davis’s life informs her historiography

One reason Women, Race, & Class feels unusually “alive” is that Davis writes history the way an organizer studies a terrain: not for trivia, but for strategy. This is the mark of someone whose own life has been a contest over narrative and legitimacy.

Consider her relationship to feminism itself. In the Guardian interview, Davis recalls being asked, in the early days, a question that now sounds absurd but was politically revealing: “Are you Black or are you a woman?” She describes the “backwardness” of strands of feminism that treated gender as separable from race and class, and she notes that this is why she resisted the label “feminist” for a period—because “women” implicitly meant white women.

That recollection is not a footnote to her book; it is one of the engines behind it. Women, Race, & Class answers that false choice by demolishing its premise. Davis argues that the very demand to choose between identities is a political technology that maintains hierarchies. It forces fragmentation where solidarity is necessary. It turns the complexity of lived experience into a loyalty test.

Her earlier criminalization also matters here. If your political life includes being fired for party membership and prosecuted for conspiracy, you develop an instinct for how institutions define legitimacy. You watch how the state narrates violence and innocence, how it frames certain people as inherently suspect. That attentiveness to narrative shows up in Davis’s treatment of rape myths, lynching ideology, and the cultural production of “respectable” white womanhood as something requiring protection—often at the expense of Black life. Women, Race, & Class reads, in part, like an autopsy of the stories America tells itself to make inequality feel natural.

Reception and legacy: A book that became a blueprint

At the time of its publication, Women, Race, & Class entered intellectual worlds that were already in motion. Black feminist organizing and writing had been developing for years, including traditions that emphasized how racism and sexism co-constitute each other. Davis’s contribution was to write a broadly accessible, historically grounded account that braided these insights into a single narrative and aimed it at both movement debates and academic discourse.

Scholarly commentary has since recognized Davis as a pioneer of “integrative” analysis of race, gender, and class—work that helped establish a field of study that would later become institutionalized. But the book’s influence extends beyond formal scholarship. It has functioned as a movement text because it provides an argument for coalition that is not sentimental. Davis’s coalitional politics is rooted in material analysis: who does what labor, who is paid, who is exposed to violence, who is represented, who is protected by law.

This helps explain why the book remains so resonant in contemporary debates about the carceral state, even though Women, Race, & Class is not primarily a “prison book.” Davis’s later abolitionist work would address incarceration directly, but the analytic through-line is visible: if you understand how power stratifies bodies and labor, you can see how prisons become a solution for managing the inequalities capitalism produces. Davis’s own abolitionist philosophy—covered in profiles and in later works—treats incarceration as a central modern technology of racial control, and her insistence on structural analysis rather than individual moralizing appears early in Women, Race, & Class.

KOLUMN Magazine, in an article examining Davis’s abolitionist legacy, frames her as interpreting criminal justice through capitalism, race, and oppression—language that echoes the same triangulated analysis readers encounter in Women, Race, & Class. When a magazine founded on cultural infrastructure claims Davis as foundational, it is pointing to something broader than biography: Davis offers a method for reading American life that is both historical and diagnostic.

Even the book’s publication and re-publication history matters. The New York Public Library-hosted PDF excerpt cites the original 1981 Random House publication and a 1983 Vintage Books edition, underscoring how the text has been kept in circulation across decades and imprints. That persistence is not automatic. Many radical texts vanish into specialized archives. Women, Race, & Class has remained a commonly available title because it continues to meet a need: it tells readers why their movements keep reproducing the same conflicts, and it offers a way to interpret those conflicts without collapsing into cynicism.

The book’s hardest truth: The myth of universal womanhood

Perhaps the most consequential thing Women, Race, & Class does is dismantle the most flattering self-image of American feminism: that it is, by default, a universal movement for women as such. Davis shows that “women” has often functioned as a political shorthand for a specific group of women—white, middle-class, socially protected women—whose problems were treated as the movement’s core problems, while other women’s experiences were treated as add-ons, exceptions, or distractions.

This is not a mere representational critique. It is a critique of political economy. If feminism is defined through the desire to escape housework, for instance, then the solution can easily become hiring someone else—often a poorer woman, often a woman of color—to do that labor. Liberation for one group can become intensified exploitation for another. Davis forces readers to ask whether a movement is challenging the structure or merely rearranging who benefits within it.

Similarly, if reproductive freedom is framed solely as access to abortion, without attention to sterilization abuse, healthcare disparities, and the history of eugenic policies, then a rights framework can mask coercion. Davis’s analysis pushes feminism away from a narrow legalism and toward a broader understanding of bodily autonomy as materially conditioned.

These arguments remain uncomfortable because they are not easily resolved by better rhetoric. They require redistribution: of resources, of attention, of leadership, of the right to define the agenda. That is why the book remains both beloved and contested. It does not allow readers to keep their innocence.

Angela Davis now: The through-line of optimism and discipline

Davis’s public life after Women, Race, & Class has been long enough to include multiple political eras: the Reagan years, the “tough on crime” 1990s, the post-9/11 security state, the rise of mass movements against police violence, and contemporary debates about abolition and Palestine solidarity. Her influence has not depended on being perfectly aligned with any one institution. It has depended on coherence: the insistence that oppression is systemic, that solidarity must be built across differences, and that optimism is not naïveté but a political resource.

In the Guardian profile, Davis describes optimism as necessary, not optional, for movements that aim at transformation: “We can’t do anything without optimism.” In the same conversation, she reflects on earlier feminist limitations and her own evolution, acknowledging the ways language and ideology shift over time. That willingness to revise without abandoning fundamentals is part of why her work remains teachable. Davis does not present herself as a finished product. She presents politics as a practice.

This practice-oriented approach helps explain why Women, Race, & Class still functions as an entry point for readers who later encounter Davis’s abolitionist writings. If you begin with her history of slavery, labor, and sexual violence, you are already being trained to see prisons not as isolated institutions but as part of the same social architecture. The book is not only about women; it is about how a society organizes humanity into hierarchies and then calls those hierarchies natural.

Why the book still matters in 2026

The simplest measure of a book’s significance is whether it predicted the future. That is not a very good measure. A better one is whether the book changed how people interpret the present. Women, Race, & Class did that, and it continues to do it.

When contemporary movements argue about whose stories are centered, about whether class politics can ignore race, about whether feminist agendas can be separated from labor agendas, about whether carceral solutions can coexist with liberation rhetoric, they are often replaying debates Davis mapped with historical specificity. When activists insist on “reproductive justice” rather than “choice,” they are echoing Davis’s critique that rights without material access and without historical memory are insufficient. When scholars teach students that suffrage history includes racist strategy, they are moving within the terrain Davis helped popularize.

The book also matters because it models a style of argument that feels increasingly rare: a willingness to criticize allies without abandoning the possibility of solidarity. Davis is not writing to score points. She is writing to make movements more capable of liberation. That makes her critique sharper, not softer. She refuses the comfort of thinking the problem is simply ignorance or bad attitudes. The problem is structure. And structure does not yield to goodwill alone.

That is why Women, Race, & Class remains indispensable for readers building institutions—magazines, nonprofits, coalitions, political campaigns—who want to avoid reproducing the exclusions they claim to oppose. It offers a history that functions like a warning label: if you do not account for race and class, your feminism will not become universal. It will become selective. If you do not account for gender and race, your labor politics will not become emancipatory. It will become partial. And if you do not account for all three, your democracy will remain what it has too often been: a promise that expands just enough to stabilize the system, while leaving the most vulnerable to carry the cost.

Davis once became famous because the state tried to make her a symbol of danger. Women, Race, & Class suggests the deeper danger was always the opposite: a politics content to free only some. In that sense, the book is not merely history. It is a test—one that each new generation keeps failing and re-taking, because the stakes remain the same.

More great stories

NAACP: When Reform Turned Into Resistance