It offers hope as a discipline—something learned from the “dark past” and insisted upon in the “present."

It offers hope as a discipline—something learned from the “dark past” and insisted upon in the “present."

By KOLUMN Magazine

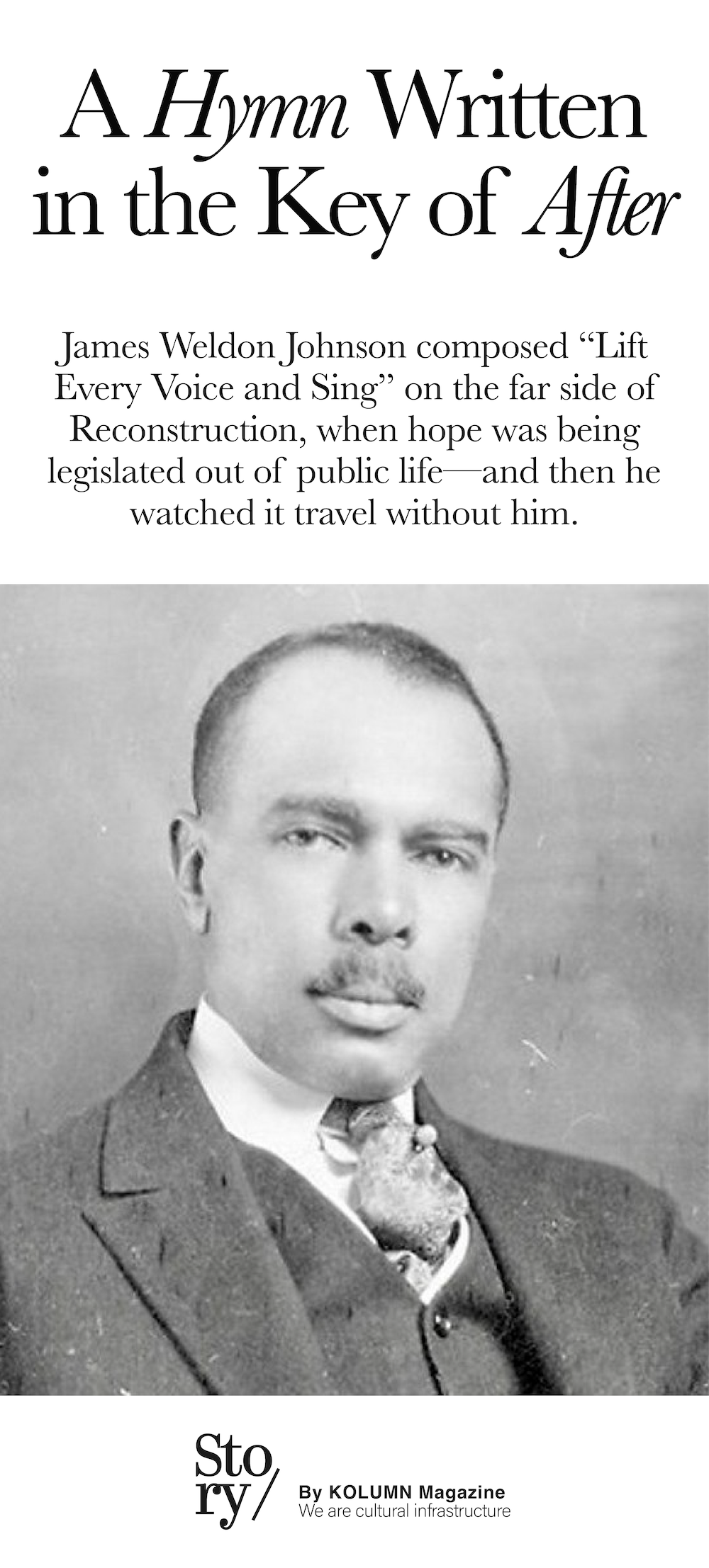

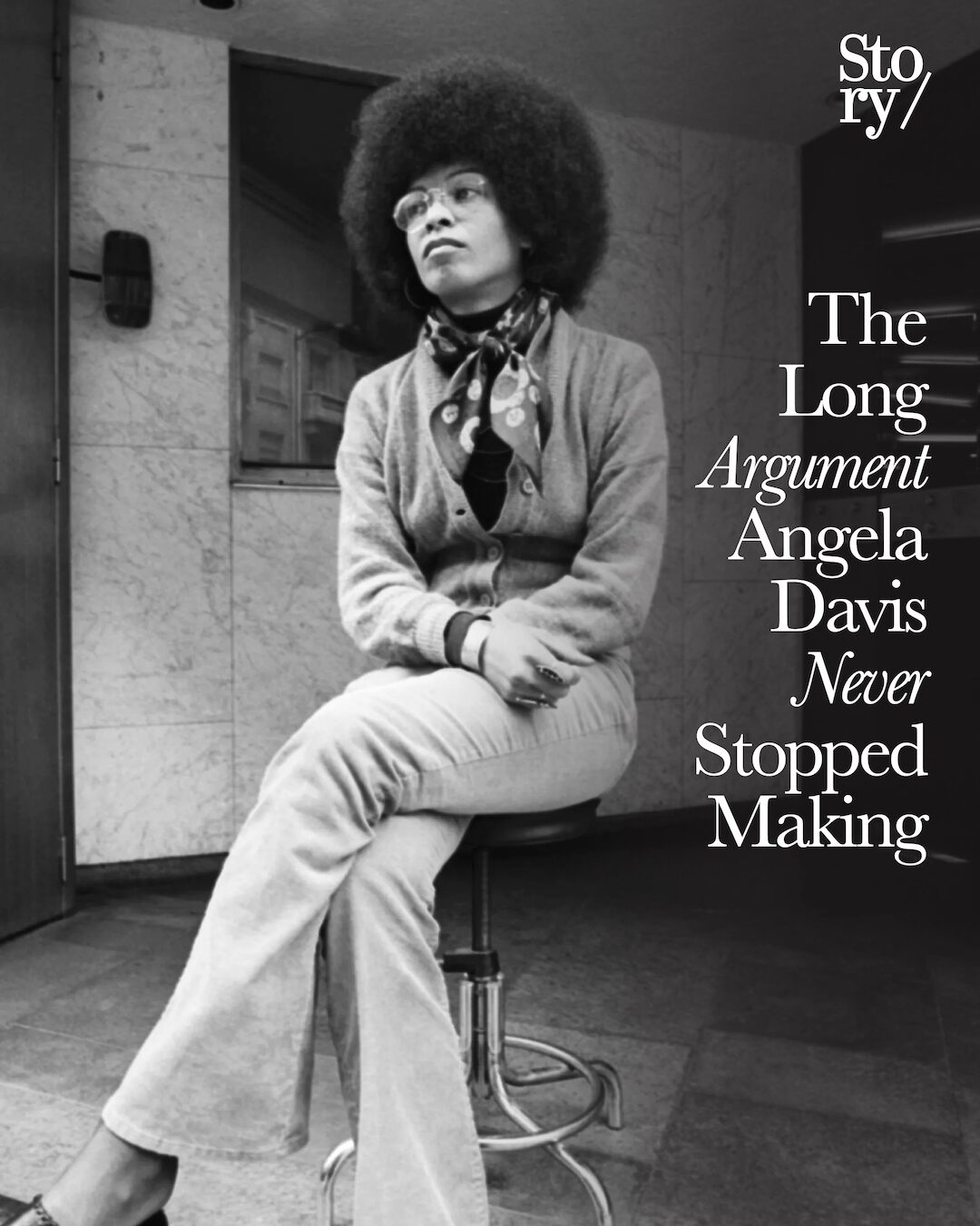

People often call it a song, an anthem, a hymn, a tradition. But it began as something smaller and more precise: a poem written by a Black school principal in segregated Jacksonville, Florida, for a single occasion—an Abraham Lincoln birthday celebration—at the turn of the 20th century. That origin story is both ordinary and astonishing. Ordinary because it starts with the kind of assignment teachers and administrators have always given themselves: create something that will make young people feel part of the world they’re inheriting. Astonishing because the poem that James Weldon Johnson drafted for that day—correctly titled “Lift Every Voice and Sing” (often mistyped as “Life Every Voice and Sing”)—did not remain tethered to its first audience. It moved, uninvited and uncontained, through Black schools and churches, through civic halls and protest marches, into the repertoire of famous voices and into the ritual life of millions of people who never learned Johnson’s name in school.

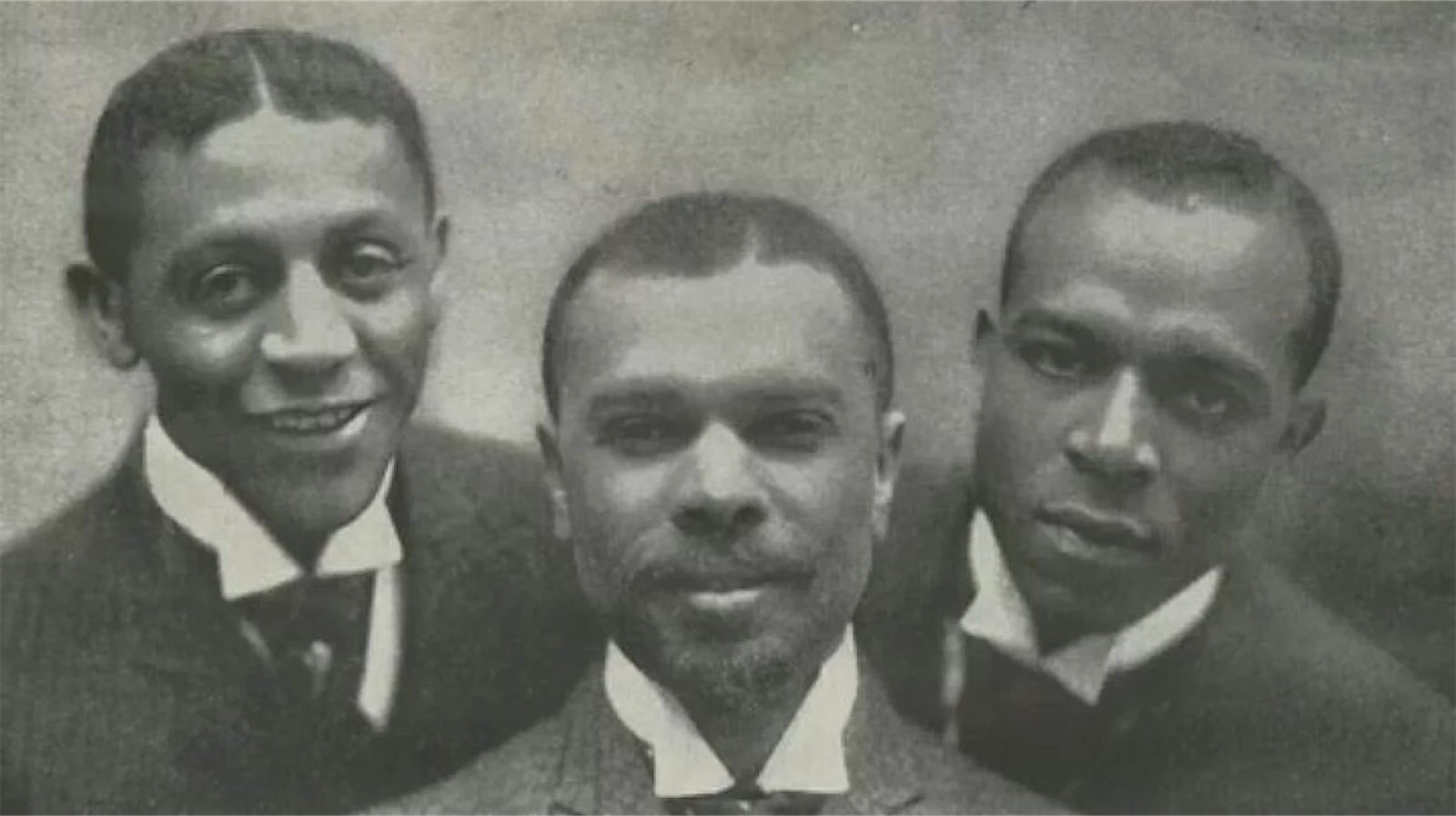

The popular shorthand for what happened next is familiar: Johnson wrote the lyrics; his brother, J. Rosamond Johnson, set them to music; a choir of 500 students first performed it publicly at Stanton School; the NAACP later embraced it as a “Negro national anthem”; generations of Black Americans carried it forward as what many now call the “Black national anthem.” Each clause in that summary is true in outline, and each clause hides a deeper story about art’s relationship to power: how culture travels when institutions don’t protect you, how memory forms when history is withheld, how a work can become a shared civic language precisely because it is not officially sanctioned.

To write about “Lift Every Voice and Sing” as a journalist—and not as a celebrant—is to hold two truths together. The first is that the poem’s endurance is a triumph of craft, faith, and communal adoption. The second is that its endurance is also an index of America’s unfinished work: the reason the song keeps returning to the public square is that the conditions it describes—weariness, chastening, blood, hope under pressure—keep returning, too. As one NPR framing puts it, the song persists in part because the struggle it names “never went away.”

A principal in a segregated city

In early 1900, James Weldon Johnson was not yet the figure many biographies would later call a “Renaissance man”—the diplomat, the NAACP leader, the Harlem Renaissance architect, the anthologist, the author. He was, more immediately, a Black educator in the Jim Crow South, charged with the practical work of building a school culture where the public world’s messages to Black children were stark: be smaller; expect less; stay in your place. The NAACP’s own account, and multiple historical summaries, locate the poem’s first public performance at the segregated Stanton School in Jacksonville, where Johnson served as principal, with 500 schoolchildren singing it for a Lincoln birthday celebration.

The choice of Lincoln’s birthday as the occasion matters. In the decades after the Civil War, Lincoln commemorations in Black communities were often both patriotic and pointed: celebrations of emancipation’s promise, but also reminders that the promise was being sabotaged—by disfranchisement, by racial terror, by the architecture of segregation. Johnson was asked to prepare remarks for the event; instead, he wrote a poem. That decision already signals something about his sensibility. Speeches are time-bound; poems can be portable. Speeches address a crowd; poems can address history.

Washington Post reporting has described the moment in similarly grounded terms: a young principal in Jacksonville, asked to mark Lincoln’s birthday, chose to write a poem rather than an ordinary address, beginning with a line that was simultaneously simple and directive: “Lift ev’ry voice and sing.”

The world around that line was not hospitable to Black aspiration. The end of Reconstruction had been followed by a wave of legal segregation and violence, and by a national willingness to treat Black citizenship as negotiable. To understand the poem’s emotional weather—its mix of marching cadence and prayerful petition—you have to hear it as an artifact from a moment when progress was not merely slow but being actively reversed. Johnson’s poem does not pretend otherwise. It begins with rejoicing, but it does not begin with ease.

“Not a startling line”: The act of composing

One of the most valuable sources on the poem’s composition is Johnson himself. In his autobiography Along This Way (published in 1933), Johnson describes writing the lyrics with a candor that undercuts the myth of effortless genius. The Library of Congress’s music blog, In The Muse, quotes his recollection: he got the first line—“Lift ev’ry voice and sing”—and judged it “not a startling line,” then “worked along grinding out the next five.” And then, as he approached the end of the first stanza, two lines arrived that changed his relationship to the piece: “Sing a song full of the faith that the dark past has taught us; / Sing a song full of the hope that the present has brought us.” Johnson writes that, in that moment, “the spirit of the poem had taken hold” of him.

This is an intimate account of composition: labor, then sudden ignition. It also tells us something about what the poem is doing rhetorically. The most quoted lines in “Lift Every Voice and Sing” are often its opening call to sing “with the harmonies of Liberty” and its closing prayer to remain “true to our God” and “true to our native land.” But Johnson’s own memory spotlights the hinge of the first stanza: faith and hope as learned practices, as things the “dark past” teaches and the precarious “present” offers. That is not generic uplift. It is an ethics of endurance, a method for surviving history without surrendering to it.

Johnson’s admission that the first line was not dazzling is also a reminder: what makes the poem powerful is not verbal pyrotechnics. It is the discipline of clarity—language sturdy enough to be sung by children and sophisticated enough to carry biblical allusion, historical grief, and political resolve without collapsing into slogan.

From poem to song: The Johnson brothers’ collaboration

If the poem’s first life was on the page, its second life was in breath. Johnson’s brother, J. Rosamond Johnson—trained in music and active in performance and composition—set the poem to music. The NAACP’s historical explainer emphasizes that partnership directly: James wrote the poem; Rosamond composed the music; Stanton School’s children gave the first public performance.

The Library of Congress preserves notated sheet music credited to both brothers, including an early 20th-century publication through E.B. Marks Music Co. That archival fact matters because it places “Lift Every Voice and Sing” inside a professional musical economy, not only inside church or school tradition. It also hints at the poem’s dual identity: art made for community use, but also art that entered the marketplace of American song.

There is a temptation to treat the move from poem to hymn as inevitable—great words naturally find music. But, historically, the transformation depended on something more contingent: the Johnson brothers’ shared artistic language and their proximity to institutions of Black education. The song did not need Broadway to be born; it needed a school. It needed children with a reason to sing together.

February 12, 1900: 500 children and a public debut

The oft-cited detail—“500 schoolchildren”—can feel like a flourish, a number polished by retelling. Yet it appears repeatedly across institutional accounts: the NAACP, PBS, and other historical summaries all describe the first public performance as being sung by a choir of 500 students at Stanton School during a Lincoln birthday celebration.

The image is worth pausing over: a segregated Black school at the dawn of a century, children assembled to honor a president whose name had become shorthand for emancipation, and a new song that refuses to speak only in gratitude. It sings of a road “stony,” of a “bitter” rod, of “blood of the slaughtered,” and then it pivots—not to vengeance but to resolve and prayer. The poem does not deny the violence of American history; it refuses to let violence have the last word.

In the 21st century, when the song surfaces in stadium ceremonies or televised events, the scale is massive and the staging deliberate. But its first performance was mass in a different sense, a congregation of ordinary voices. The song’s power has never depended on virtuosity. It depends on collective sound.

What the lyrics are doing: A civic prayer with a historical spine

Read on the page—at the Poetry Foundation or the Academy of American Poets—“Lift Every Voice and Sing” reveals a careful architecture. (The Poetry Foundation) It opens with an imperative (“Lift every voice…”) and immediately makes the act of singing do civic work: to ring earth and heaven with “the harmonies of Liberty.” In the first stanza, Johnson uses sound itself—ringing, resounding, rolling—as a model of freedom. Liberty is not only a legal status; it is a vibration that should reach everywhere.

Then he gives history a body. The second stanza moves through chastening, weary feet, tears, blood, and the movement from “gloomy past” to the “white gleam” of a “bright star.” That star language can be heard as aspiration, but it also carries the era’s racialized metaphors of light and darkness, repurposed here: “white gleam” as a distant possibility rather than a racial hierarchy. Johnson’s imagery is not naive. It is aspirational under duress.

The third stanza shifts fully into prayer, naming God as “God of our weary years” and “God of our silent tears.” The language suggests a long intimacy with endurance, with suffering that has not been publicly acknowledged. And the final ask is not abstract. It is specific: keep us on the path, lest we forget, lest we become drunk on the world, lest we lose our way. This is why the song has lived so naturally inside Black churches: it is structured as a liturgy, a communal confession and petition.

At the same time, it is also unmistakably political. It does not demand assimilation; it demands fidelity—to God and to “our native land.” That last phrase is one reason the poem has been so effective as a civic claim. It insists that Black Americans are not guests asking for inclusion; they are natives asserting ownership of the nation’s moral future.

How a local piece became a regional tradition

Johnson’s autobiography describes something historians recognize as a common mechanism of Black cultural transmission: the schoolchildren kept singing it; they carried it into other schools; they became teachers and taught it to other children; and, over time, it spread widely. That kind of propagation—informal, relational, anchored in institutions Black communities built for themselves—is how many “standard” texts become standard when mainstream institutions ignore them.

This is also why “Lift Every Voice and Sing” can feel older than it is. When a song enters the core rituals of schooling, worship, and community gatherings, it compresses time. It becomes not merely something you know, but something you inherit. You learn it before you can fully interpret it. And then, as adulthood clarifies what childhood could not, the lyrics open like a locked room.

The NAACP and the making of an anthem

By the early 20th century, the song was no longer only a Jacksonville artifact. The Library of Congress’s National Recording Preservation Board notes that the NAACP’s colleagues honored Johnson by proclaiming the song “the Negro national anthem,” an “informal designation” that reflected its popularity in Black schools, organizations, and churches and helped it take on new meanings as Black migrants spread across the nation.

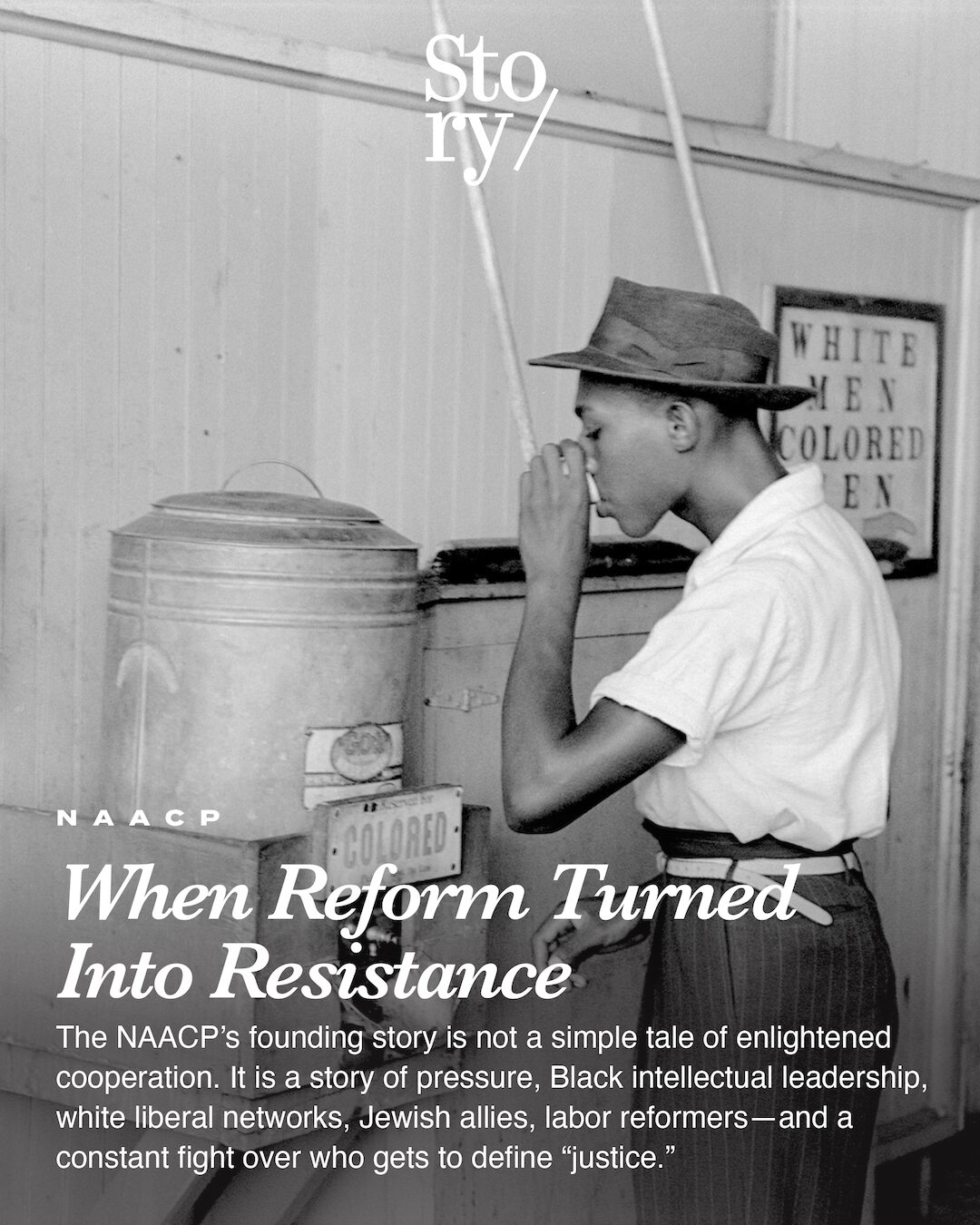

Many contemporary accounts summarize that institutional embrace as occurring in 1919, when the NAACP dubbed it the “Negro national anthem.” That framing—anthem—matters, because it shifts the song’s function. A hymn is for worship; an anthem is for collective identity in the civic sphere. In the Jim Crow era, when Black citizenship was violently contested, naming a “national anthem” was a form of counter-sovereignty: a declaration that Black people constituted a nation within the nation, bound by common struggle and common aspiration, even when the state refused full belonging.

It is also important, journalistically, to recognize what the NAACP did not do: it did not invent the song’s power. It recognized and amplified power that already existed through community use. Institutions can codify what people have already decided with their bodies.

The song’s afterlives: Recordings, registers, and reinventions

One measure of a song’s durability is how often it gets recorded and reinterpreted. The Library of Congress’s music blog notes that two recordings associated with “Lift Every Voice and Sing” were selected for the 2016 National Recording Registry: a 1923 rendition by the Manhattan Harmony Four and a 1990 recording led by Melba Moore with an ensemble of major artists.

That detail is more than trivia. It places the song in two distinct cultural moments. The early recording era captures a period when Black-owned labels and Black performance networks were carving space in a segregated industry. The 1990 project signals a modern revival effort—an explicit attempt to bring the song’s power to new generations through star wattage. The song can accommodate both: it is intimate enough for congregational singing and capacious enough for orchestration.

And then there are the reinventions that are less about musical arrangement and more about context. The song appears in memoir and literature, in film and ceremony, often as shorthand for Black communal life. It functions as a cultural cue: this is a Black space, a Black gathering, a Black claim on the American story.

2020 and after: The resurgence that wasn’t really a resurgence

In the summer of 2020, amid nationwide protests following the murder of George Floyd, “Lift Every Voice and Sing” reentered mainstream headlines. TIME described this as a “newly resurgent” moment, noting the song’s deep history and its renewed presence in public life.

But for many Black Americans, calling it a resurgence misses the point. The song had never stopped being sung. What changed was not Black practice; it was wider visibility—especially through major institutions like the NFL. Reuters reporting, for example, describes the league’s inclusion of the song in prominent events beginning in the wake of 2020, and also notes the controversies and backlash that sometimes accompany its performance.

This is where the song’s meaning becomes contested in new ways. When a hymn born in segregated Black schooling is staged as a pregame ritual in a multibillion-dollar entertainment enterprise, questions follow: Is this recognition, co-optation, or something messier—both at once? Is the performance a meaningful civic gesture, or a symbolic substitute for material change? A Reuters fact-check from 2024 underscores how politicized the conversation has become, debunking false claims that the NFL “banned” the song and clarifying that it has continued to be performed at major games.

In other words, “Lift Every Voice and Sing” now functions not only as a song but as a proxy debate about American identity. That debate often reveals less about the song itself than about the listener’s relationship to Black history. To object to the song’s presence is frequently to object to what it implies: that the nation’s official narrative is incomplete without Black testimony, and that “liberty” cannot be harmonized if some voices are expected to sing quietly.

What Black media has emphasized in the present tense

Black publications have approached the song’s modern visibility with a different texture than mainstream political coverage. Ebony, for instance, has recently framed the song’s Super Bowl appearances by returning to its origin—poem, brother’s music, first public performance—and by asking why the ritual matters now. Word In Black has covered contemporary commemorations—including events marking the song’s 125th anniversary—emphasizing how people grow into the song’s meaning over time, and how it continues to function as spiritual and cultural infrastructure.

This attention to lived experience is crucial. “Lift Every Voice and Sing” is not only an artifact to be analyzed; it is a practice. Many people encounter it as children, often without full comprehension, and then revisit it as adults with a different vocabulary for the same feelings: grief that has not been publicly mourned, pride that does not require permission, faith that functions as strategy.

In this sense, the song’s endurance is not primarily a triumph of publicity. It is a triumph of pedagogy—Black communities teaching themselves, across generations, how to name their past without being trapped by it.

KOLUMN Magazine, memory, and monument

Cultural works accrue monuments. Sometimes those monuments are literal. KOLUMN Magazine has noted, in its reporting on artist Augusta Savage, that her monumental 1939 World’s Fair sculpture—known as Lift Every Voice and Sing and also called The Harp—depicted a choir of Black singers arranged as the strings of a harp, a visual translation of collective voice into form.

That detail shows how quickly “Lift Every Voice and Sing” expanded beyond music into a broader Black symbolic vocabulary. A poem became a song; a song became an anthem; an anthem became an image—choir as architecture, voice as structure. Savage’s sculpture is, among other things, a thesis: Black collective expression is not decorative. It is load-bearing.

The central paradox: A national hymn that isn’t the national hymn

One of the most revealing facts about “Lift Every Voice and Sing” is that it has never needed federal designation to function as a kind of national hymn. It has operated as such through practice, not law. The Library of Congress’s registry page notes its longstanding role as the “Black National Anthem” and the difficulty of capturing its meaning in any single recording—an admission that the song’s essence is not an arrangement but a relationship between words, history, and people.

And yet the desire to label it—Black national anthem, Negro national anthem, unofficial anthem—keeps recurring. Labels can honor, but they can also flatten. The song’s original achievement was to be specific and expansive at once: rooted in the Black experience of post-Reconstruction America, yet written with a moral universality that makes it legible beyond that context without surrendering its core.

This is why “Lift Every Voice and Sing” unsettles some listeners. It is not a request for inclusion that can be granted and then forgotten. It is a demand that memory be part of patriotism, that faith be part of politics, that liberty be measured not by slogans but by conditions on the ground.

Craft, theology, and the politics of hope

There is an easy way to talk about the song: as inspiration. Johnson’s own account makes clear that inspiration was only part of the process. The rest was work—grinding out lines until the poem’s spirit “took hold.”

What “Lift Every Voice and Sing” ultimately offers is not optimism, at least not the cheap kind. It offers hope as a discipline—something learned from the “dark past” and insisted upon in the “present.” In the poem’s world, hope is not a feeling that arrives when conditions improve; it is an instrument for moving conditions. That is why the song can be sung in joy and in grief. It is built for both.

Theologically, the poem’s final stanza can be read as a warning against two temptations: despair and forgetting. The prayer asks to be kept on the path, to remember God, to remember the struggle, to remain faithful. It does not ask to be made comfortable. It asks to be made steady.

Politically, that steadiness is a form of resistance. In a country that has repeatedly tried to legislate Black people out of full belonging, steadiness becomes radical. Collective singing becomes evidence: we are here; we remember; we persist.

Why the origin story still matters

At stadium events, “Lift Every Voice and Sing” is sometimes treated as a contemporary gesture, a response to the politics of the moment. The sources tell a different story: it was written in 1900 as a poem for a Black school community, first performed by 500 children in Jacksonville, later embraced by the NAACP, preserved in archives, and carried forward through everyday ritual long before it ever became a headline.

That history matters because it counters the idea that the song is an “add-on” to American civic life. The song is older than many of the institutions now debating it. It predates the adoption of “The Star-Spangled Banner” as the official U.S. national anthem, a fact the Washington Post has pointed out in contextual reporting.

More importantly, the origin story matters because it reminds us what the song was built to do: to give Black children a language big enough to hold their history and their future. It was built to be sung by the people most often told they should not be heard.

The poem’s most enduring instruction

In the end, the most striking thing about “Lift Every Voice and Sing” is that it does not only narrate suffering. It issues an instruction about what to do with suffering: sing—together—until your sound is large enough to reach earth and heaven. That is not escapism. It is a blueprint for survival and solidarity, drafted by a principal who understood that children needed more than facts. They needed a way to belong to a future.

Johnson could not have known that a poem written for one day would become a century-spanning ritual. But he did know, in the act of writing, that something had taken hold of him—something more than an assignment, something closer to calling.

And perhaps that is the simplest, truest explanation for why the song remains: because it was never only a song. It was a method—of remembering, of marching, of praying, of insisting—set to melody so it could travel.

More great stories

NAACP: When Reform Turned Into Resistance