The ideology that made him a prisoner was not only a set of beliefs; it was a system that organized society through exclusion and fear. Systems like that rarely announce themselves with camps at the beginning. They begin with categories, with laws, with the slow narrowing of who counts.

The ideology that made him a prisoner was not only a set of beliefs; it was a system that organized society through exclusion and fear. Systems like that rarely announce themselves with camps at the beginning. They begin with categories, with laws, with the slow narrowing of who counts.

By KOLUMN Magazine

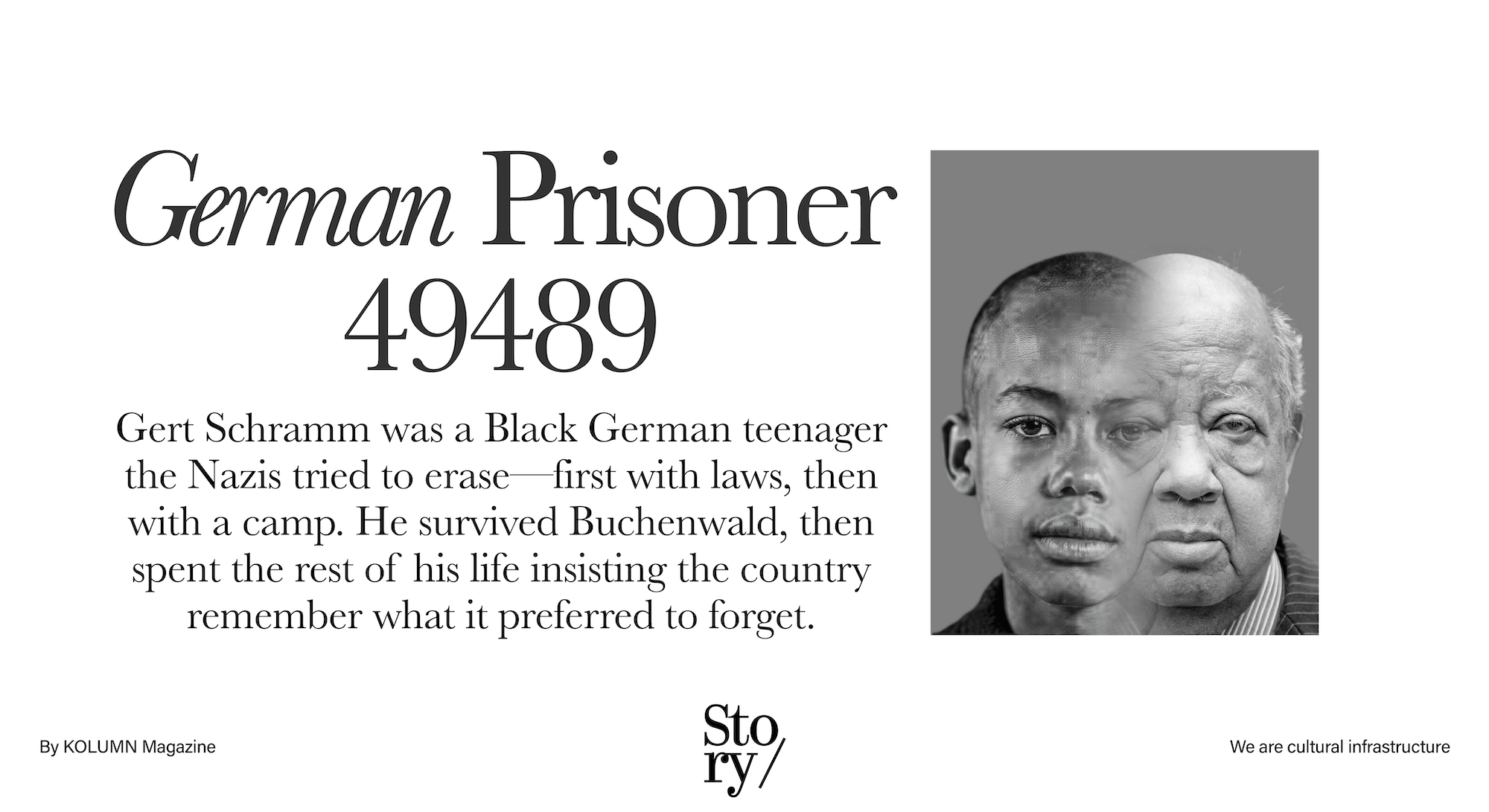

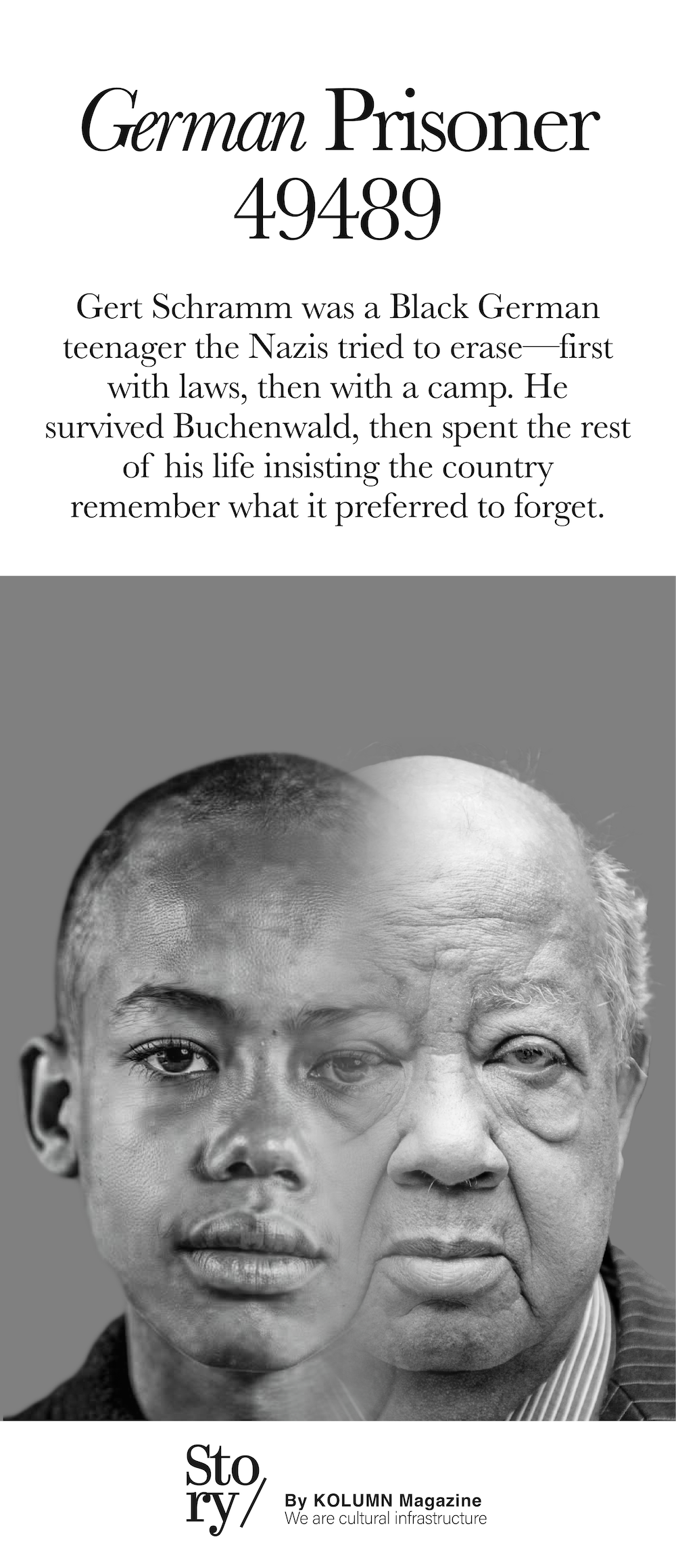

In the architecture of Holocaust memory, certain images have become almost fixed: barbed wire against winter sky, watchtowers silhouetted at dusk, the striped uniform reduced to an icon. Those images are necessary, but they can also flatten the story into something that feels—dangerously—already known. Gert Schramm’s life resists that flattening. It does so not by competing with the central facts of the Nazi genocide, but by widening the frame in which those facts are understood. Schramm—born in Erfurt in 1928, the child of a German mother and an African American father—was sent to Buchenwald as a teenager and survived. In later decades he became a public witness, speaking in schools and civic halls, arguing against the return of far-right politics, and forcing Germans to confront an uncomfortable truth: Nazi racial ideology did not only target Jews, Roma and Sinti, disabled people, political opponents, and others; it also worked to police Blackness, mixed heritage, and the boundaries of “Germanness” itself.

Schramm’s story is not widely known in the United States, and it is only intermittently present in the English-language press. That absence is itself instructive. In Germany, his name surfaces in local and national reporting, in memorial institutions’ archives, and in Afro-German civic debates about commemoration. Yet outside Germany, the narrative of “the Holocaust” is often told with a kind of schematic precision: as if the categories of Nazi persecution were self-contained, and as if Germany’s Black history were something that begins later—with postwar migration, guest workers, or American soldiers. Schramm unsettles that chronology. He forces a reckoning with the fact that Black life existed in Germany long before 1945, and that the Nazi state had a vocabulary—both legal and bureaucratic—for marking certain bodies as incompatible with the national future.

To write about Schramm responsibly is to write about two Germanys at once: the Germany that made a teenager’s skin color a matter of state interest, and the Germany that later asked him—often in the same breath—to educate the public and to accept the limits of its attention. He survived Buchenwald in part because other prisoners made the decision that he would survive. He became a witness because he decided, later, that survival without testimony was a second kind of erasure.

A boy made “illegal”

Gert Schramm entered the world in a country still haunted by the First World War and already rehearsing the racial fantasies that would harden under National Socialism. He was born in Erfurt, in Thuringia, in late 1928. Accounts of his parentage converge on the same essential facts: his mother, Marianne Schramm, was German; his father was an African American engineer connected to U.S. industry working in Germany on contract. In later retellings, his father’s name appears as Jack Brankson (and in some sources with slight spelling variants), a detail that matters not for pedantic correction but because the archival record of Black lives—particularly those cross-cut by war, deportation, and bureaucratic violence—is often fragmented and inconsistent. That fragmentation is one of the legacies Schramm’s testimony pushes against.

Schramm grew up in towns around Thuringia, including Witterda and Bad Langensalza, in a social landscape where a child like him could be simultaneously visible and unseen: visible as an object of curiosity, mockery, or threat; unseen as a citizen with claims on the nation. The Nazi seizure of power in 1933 did not invent anti-Black racism in Germany, but it weaponized it—folding everyday prejudice into a state project that elevated “Aryan” purity into a governing principle. The regime’s racial laws narrowed the economic and social possibilities for Black and mixed-race people, policing relationships, restricting education, and subjecting some to forced sterilization.

For Schramm, these structures were not abstract. In adolescence he wanted vocational training, the kind of working-class path that could turn a mechanically gifted boy into a tradesman and, eventually, an engineer. But under the racialized logic of the state, the door to formal apprenticeship was closed. He worked instead as a helper in a car repair shop—close enough to the craft to taste it, barred enough to understand the insult. The message embedded in that restriction was unmistakable: he could contribute labor, but he was not meant to accumulate credentials; he could work, but he was not meant to advance.

In Nazi Germany, racial ideology was not simply social sentiment; it was administrative practice. It lived in forms, in classifications, in police files. It also lived in the laws that criminalized intimate life across racial lines. The U.S. Holocaust Memorial Museum’s encyclopedia makes clear that Black people in Germany faced harassment and discrimination and that the regime’s racial policies constrained their opportunities and lives. These policies operated alongside, and sometimes intersected with, the broader machinery of Nazi persecution.

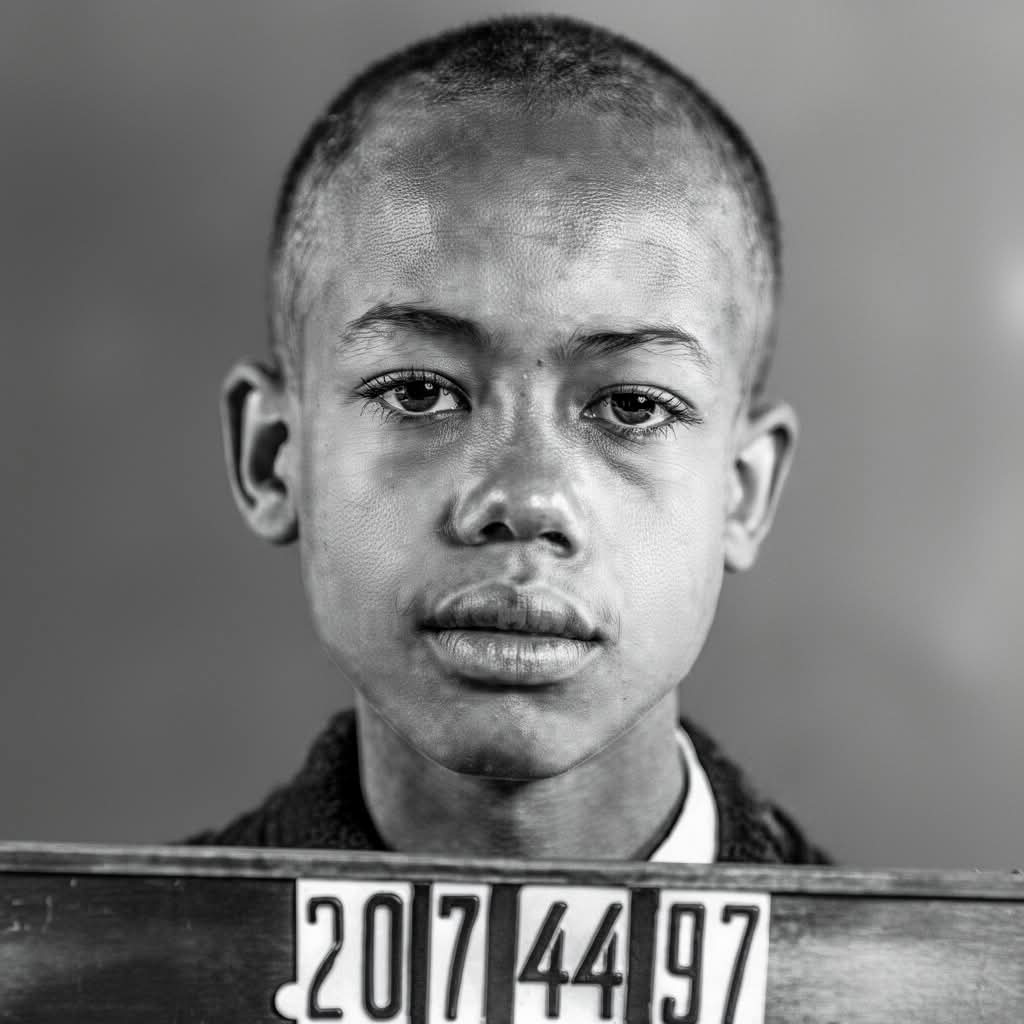

Schramm’s adolescence unfolded with this pressure as a constant background hum, until it became a direct assault. In 1944, he was arrested by the Gestapo and held in custody. Sources differ on certain precise dates in ways typical of life histories reconstructed across decades, but they align on the central arc: he was taken as a teenager, interrogated, abused, and eventually deported to Buchenwald in July 1944, where he received the prisoner number 49489.

If the number is one of the facts most often repeated, it is because it captures the logic of the camp system: the conversion of a person into an entry. But Schramm’s story adds a further detail that makes the conversion feel even more brutal. On documentation connected to his imprisonment, his skin color was recorded with a descriptor—“kaffeebraun,” coffee-brown—language that belongs to the world of commodity and measurement, not humanity. Institutions like the Wiener Holocaust Library, in describing archival traces of Black and mixed-race people in the Nazi camp system, point to Schramm’s prisoner documentation as an example of how bureaucracy recorded race in the same breath as incarceration.

Buchenwald as a world

Buchenwald was not an extermination camp in the narrow sense associated with industrialized killing centers like Auschwitz-Birkenau, but it was a site of mass death, forced labor, terror, and systematic dehumanization. Prisoners were worked to exhaustion, beaten, starved, and murdered; others died from disease, exposure, and brutality. The camp’s system depended on an internal hierarchy that could turn prisoners into functionaries and make survival contingent on labor assignments, networks, and luck.

Schramm arrived as a teenager—15 years old, according to multiple accounts—carrying the kind of vulnerability that the camp exploited. Youth could be a liability. So could visibility. Schramm’s testimony and later reporting emphasize how rare Black prisoners were in Buchenwald, and how that rarity itself became a threat: to stand out at roll call, to be noticed by an SS guard, could be the difference between another day and sudden death.

In popular retellings, Schramm is sometimes described as the only Black prisoner at Buchenwald; in other accounts, he is described as the youngest among a small number of Black prisoners. The precise count varies by source and definition—whether one means Black prisoners in the main camp, across subcamps, or documented at a given time. What is not in dispute is the extreme rarity of Blackness in that environment and the way the Nazi racial state marked him as an anomaly to be contained. The fact that even the number of Black prisoners can become slippery is part of what makes Schramm’s testimony so important: it is a corrective to historical habits that treat Black presence in Nazi Europe as marginal or anecdotal.

Accounts of his camp labor emphasize the stone quarry, one of the most lethal assignments. In the quarry, the work was punishing and the body’s decline could be rapid. In that landscape, Schramm’s survival hinged on something that is easy to romanticize but difficult to fathom: solidarity under terror. Schramm credited political prisoners—Communists within the camp’s prisoner society—with saving his life, arranging for him to be shifted out of the most murderous labor and shielding him during roll calls by literally surrounding him so that his weakened state would not draw attention. One of the reasons this detail matters is that it disrupts a simplistic moral geography of the camps in which everyone is reduced to victimhood. Buchenwald contained victims, yes, but it also contained choices—imperfect, coerced, dangerous choices—about who would be protected and who would be abandoned. Schramm’s account insists that those choices existed and that his life was one of their outcomes.

In later interviews, Schramm spoke of trying not to be seen—an irony, given that he would spend much of his later life insisting on being heard. The survival strategies he described were sometimes literal: hiding his body from an SS man’s gaze, making himself small in a system designed to notice weakness. It is impossible to read those details without understanding the psychology of constant threat. Survival in a camp was not only an endurance of hunger and labor but a daily negotiation with attention: when to speak, when to look down, when to disappear.

Buchenwald was liberated in April 1945, and the date—April 11—appears repeatedly in memorial timelines as a marker of the camp’s end as an SS-controlled space. Schramm survived to see that day. Later, he would write and speak about the “Buchenwald Oath,” the vow made by survivors to build a world free of fascism and war. In some accounts, that oath becomes a pivot in his life story: a moment when survival is reinterpreted as obligation. The oath is often quoted in German commemoration culture, but what matters in Schramm’s story is less the ceremonial language than the lived consequence: he would eventually treat his life after Buchenwald as an extension of the duty to testify.

After the camp: Work, family, and the long shadow of race

The postwar chapters of survivor lives are often narrated as “after”—as if liberation ended the story. Schramm’s biography illustrates how misleading that can be. After 1945 he returned to Thuringia and began building an adult life in a divided Germany. He worked in industrial jobs, including at the Wismut uranium enterprise in the Soviet occupation zone, and later spent years working in a coal mine in Essen in West Germany before moving back to East Germany. Over time he developed technical credentials and held positions of responsibility in transport and engineering-related work in Eberswalde, where he lived for decades.

This trajectory complicates tidy narratives about Cold War Germany. A Black German survivor moved between systems, working in industries that powered the economic life of both West and East. He was neither a simple symbol of one side nor a convenient morality tale for the other. His identity as a survivor, a worker, and a Black German did not map cleanly onto the ideological boundaries of the era.

Schramm later became associated with civic roles that suggest rootedness: involvement in local organizations, volunteer activities, and public service. At the same time, his life in later decades unfolded during the rise of neo-Nazi youth cultures, particularly in parts of the former East, where far-right violence and intimidation were a visible social threat. A television documentary from the early 2000s, referenced in biographical summaries, framed him as someone who had survived Nazis only to be threatened by skinheads—an encapsulation that risks sensationalism but also captures a grim continuity: racism does not vanish when regimes fall; it mutates and returns, often wearing the language of “tradition” or “national pride.”

Schramm’s memoir—published in German as Wer hat Angst vorm schwarzen Mann. Mein Leben in Deutschland—signals, even in its title, this attention to continuity. The phrase is associated with a traditional children’s chasing game in German-speaking contexts (“Wer hat Angst vorm schwarzen Mann?”—“Nobody!”), a ritualized taunt that historically refers not to race but to a folkloric “black man” figure tied to fear and death. But in a modern racial context, the phrase cannot help but ring with double meaning. Schramm’s choice to use it as the title of his life story reads as a deliberate provocation: an insistence that Germany’s language games and childhood rhymes sit uncomfortably beside its racial history, and that the fear the Nazis institutionalized did not disappear from the culture simply because the war ended.

The memoir’s publication date in 2011 is corroborated by bibliographic listings and educational-history projects in Germany that cite his book as a primary source for youth-oriented Holocaust education. Those projects often frame his motivation in direct terms: he wrote so that those who did not live through the era would still “know,” and so that the record would not depend solely on institutional voices.

The witness as a public figure

Holocaust testimony is frequently described in moral terms—“bearing witness,” “speaking so it never happens again.” Schramm’s public life shows how concrete and politically contested that work can be.

In Germany, survivor testimony is entwined with institutional memory: memorial sites, foundations, anniversaries, school curricula. Schramm participated in this world not as a passive invitee but as someone embedded in it. Biographical profiles place him in association with Buchenwald memorial structures and survivor organizations. Over time, he spoke to students and the public, and his account became part of how Germany taught the camp system to new generations.

The work of testimony is also work against denial and minimization. In recent decades, European far-right movements have often tried to soften the moral edge of Nazi history—through relativization, nostalgia, or the rhetorical move of claiming to be “tired” of remembrance. Survivors who speak publicly become obstacles to that project, precisely because they insist on specificity: a date, a number, a face, a prison card, a memory of a beating. Schramm’s witness role was particularly disruptive because it refused a narrow definition of who counts as a “typical” German victim of Nazism. His existence punctured a comforting national story in which racism is always imported and never native, always American and never German.

In 2014, the German state recognized Schramm’s civic contribution with the Federal Cross of Merit (Bundesverdienstkreuz). The announcement and coverage, including by the Initiative Schwarze Menschen in Deutschland (ISD), explicitly linked the honor to his educational work and his engagement against right-wing extremism. The language used in the commendation is notable: it frames memory as an active defense of democracy—something fragile, something that requires people who “remind and warn.” That framing is not incidental. It suggests that the state saw Schramm not only as a survivor but as a civic actor whose testimony had contemporary political value.

This recognition also places Schramm within a broader conversation about Afro-German history and visibility. For decades, Black Germans have argued that German public memory tends to either erase Black presence or treat it as exceptional. Schramm’s public role did not solve that structural problem, but it offered a counterexample with official weight: a Black German survivor honored for safeguarding democratic memory.

The politics of place: Naming and the fight over commemoration

In the years after Schramm’s death in April 2016, his legacy continued to appear in a new arena: the politics of place names. In Germany, debates over street names—particularly those tied to colonialism, militarism, or nationalism—have become a focal point for public history. Schramm’s name surfaced in this context in Erfurt, the city of his birth, where activists and community groups pushed for commemorations that would make Afro-German history visible in the everyday map of the city.

A reflection published by Stiftung Gedenkstätten and related materials describe efforts—alongside the Initiative Schwarze Menschen in Deutschland—to rename an area in Erfurt in his honor, noting his imprisonment in Buchenwald as a 15-year-old and explicitly quoting how the SS recorded his classification on the prisoner card. That detail is chilling not only for its racism but for how casually it sits inside a sentence: “Politisch – Negermischl. 1. Grades.” A life reduced to a slur and a bureaucratic fraction.

What does it mean for a city to rename a street after someone? In the abstract, it is symbolic. In practice, it is a redistribution of honor. It is an argument about whose stories deserve to be embedded in routine life—on mail, on street signs, on the mental maps children build as they learn where they live. The debates over Schramm’s commemoration underscore that memory is not only about museums and anniversaries; it is also about infrastructure, and about who gets to appear as part of the city’s “normal” history.

Schramm’s life makes this form of commemoration especially resonant because he spent decades pushing against the logic of marginality. He wrote his memoir not as a footnote to German history but as German history—told from a body the nation once marked as incompatible with itself. Naming a street after him is, in that sense, an inversion of Nazi intent: a public inscription where the Nazis sought disappearance.

Why his story matters now

It would be possible to treat Schramm as a singular figure: “the Black boy who survived Buchenwald,” the rare witness, the exception that proves the rule. But that framing risks making him a curiosity rather than a lens. His real significance lies in what his life reveals about systems—how racism becomes law, how law becomes incarceration, how incarceration becomes memory, and how memory becomes contested again when political conditions change.

Schramm’s biography intersects with at least four major historical conversations.

The first is the history of Black people in Germany. The U.S. Holocaust Memorial Museum notes the Nazi persecution of Afro-Germans and Black people in Germany, emphasizing harassment, discrimination, and the constriction of life chances under the racial state. Schramm’s life gives that overview a face and a chronology: a childhood in Thuringia, a denied apprenticeship, an arrest, a deportation, and later a lifetime of navigating German society across multiple political systems.

The second is the history of the concentration camp system as a racial project broader than antisemitism alone. To name that breadth is not to dilute the specificity of the Holocaust against Jews; it is to understand how Nazi racial ideology operated as a totalizing worldview. Institutions like the Wiener Holocaust Library, in documenting Black and mixed-race people in the Nazi camp system, show how bureaucratic traces exist even for people later written out of the dominant narrative. Schramm’s prisoner documentation becomes evidence not only of his suffering but of the regime’s determination to categorize and subordinate.

The third is the ethics and politics of testimony. Survivor testimony is often requested as a public good, but it can also be a burden placed disproportionately on the surviving. Schramm accepted that burden, but he did not do it quietly. His recognition with the Bundesverdienstkreuz was tied explicitly to his anti-extremist engagement and educational work, signaling that his testimony functioned as a form of democratic labor. In an era when far-right parties and movements have grown louder across Europe, that framing becomes urgent: memory is not passive inheritance; it is an active practice.

The fourth is the way nations choose their heroes and their mirrors. Schramm is both. He is heroic in the simple sense that he endured what was designed to destroy him. But he is also a mirror that reflects uncomfortable continuities: the persistence of racism after 1945, the temptation to narrow the category of “German,” and the periodic resurgence of political movements that trade on exclusion.

There is, too, a quieter significance in the particularity of his postwar life. Schramm did not become famous in the way some survivors did; he built a working life, raised a family, lived in Eberswalde. He did not, by most accounts, seek celebrity. He sought something more difficult: a kind of normal life that did not require him to lie about what he had lived through, and a public memory that did not require him to disappear in order for others to feel comfortable.

The limits of recognition—and what it demands of journalism

In practice, Schramm’s life is better documented in German sources, memorial institutions’ archives, and specialized scholarship than in major English-language newspapers. The gap between western reporting and specific German sources matters. It suggests that even as the Holocaust is a global reference point, the stories that travel internationally are often those that fit established narrative expectations.

Schramm’s life does not fit easily. It requires the reader to hold multiple truths at once: that Nazi Germany’s anti-Black racism was real and consequential; that Black German history is not an appendage to American history; that the camp system’s victims cannot be reduced to a single identity; and that postwar democracy can honor a witness while still leaving his story peripheral.

Journalism, at its best, is not only the recording of what is already famous. It is also the correction of what has been made obscure—by power, by habit, by the inertia of repetition. Gert Schramm’s life asks for that kind of correction. It asks for a telling that is not satisfied with the iconography of atrocity but follows a person through the long, uneven terrain of survival: from the paperwork that tried to define him as a problem, to the number that tried to erase his name, to the speeches in classrooms where he insisted the future belongs to those who remember accurately.

Schramm died in April 2016, after years of public work as a contemporary witness. The dates, like so many in survivor history, can feel like punctuation. But punctuation is not closure. The meaning of his life is still under negotiation—in street names, in memorial archives, in the willingness of institutions to treat Black German experiences as central to German history rather than tangential.

If there is a single lesson that Schramm’s story presses upon the present, it is this: the ideology that made him a prisoner was not only a set of beliefs; it was a system that organized society through exclusion and fear. Systems like that rarely announce themselves with camps at the beginning. They begin with categories, with laws, with the slow narrowing of who counts. Schramm lived long enough to see Germany rebuild itself on democratic foundations—and long enough to recognize how fragile those foundations can be when memory is treated as optional.

He did not let it be optional.

More great stories

Gloria Blackwell: Miss Movement