The late 1960s were not only a peak of civil rights organizing; they were also the moment when “law and order” became a dominant political language, often coded and deployed against Black freedom movements.

The late 1960s were not only a peak of civil rights organizing; they were also the moment when “law and order” became a dominant political language, often coded and deployed against Black freedom movements.

By KOLUMN Magazine

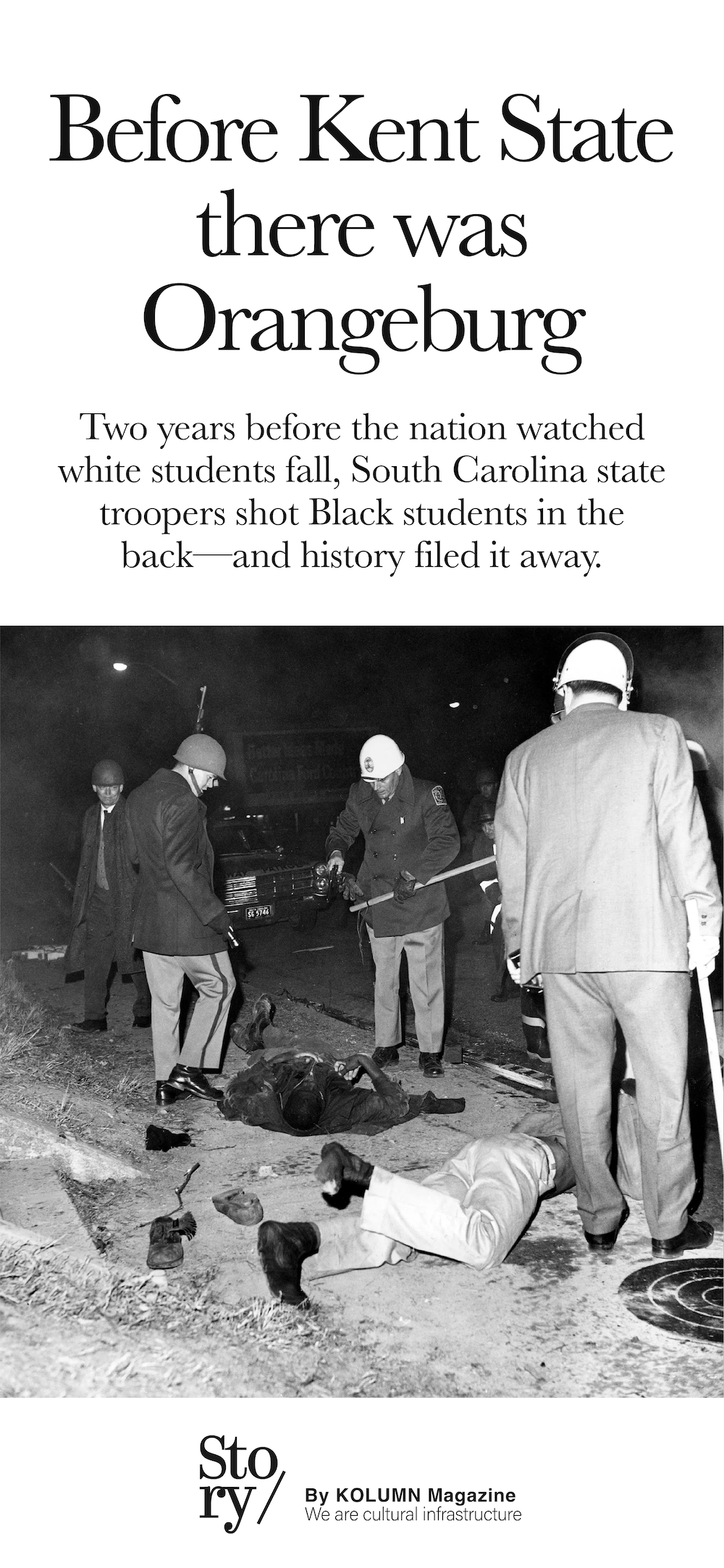

The Orangeburg Massacre sits in a strange alcove of American memory: close enough to the center of the civil rights era to be unmistakably part of its story, yet too often treated as a footnote to other, better-lit tragedies. On the night of February 8, 1968, South Carolina Highway Patrol troopers opened fire on a crowd of mostly Black students near the campus of South Carolina State College (now South Carolina State University) in Orangeburg, killing three young Black men and wounding dozens more. The dead were Samuel Hammond Jr. and Henry Smith—both students at the college—and Delano Middleton, a local high school student. Twenty-eight people were reported wounded, many struck from behind as they fled.

It is tempting, in a media culture that organizes the past into icons, to describe Orangeburg chiefly by comparison: it happened before Kent State. That is true in the calendar sense, and the contrast has been sharpened by decades of uneven public attention. But Orangeburg deserves more than the role of precursor. It clarifies how a community can live inside the overlap of segregation’s afterlife and the state’s coercive power—how a “local dispute” over a bowling alley can become, in an instant, a mass shooting; and how legal processes can resolve culpability without resolving truth.

To understand Orangeburg is to trace the connective tissue of late Jim Crow: the stubborn daily humiliations that persisted after federal law declared them illegal; the student activism that treated those humiliations as intolerable; the reflexive policing that framed Black protest as disorder; the political incentives that rewarded force; and the national news cycle that often measured racial violence by the perceived “universality” of its victims. Orangeburg reveals not only what happened on a February night in South Carolina, but also how a nation decides which dead will symbolize an era and which will be left to the care of local mourners.

A “whites only” sign in the age of civil rights law

In 1968, Orangeburg was a majority-Black city in a majority-Black county, anchored by two historically Black institutions: South Carolina State College and neighboring Claflin College. The local Black middle class, student body, and civil rights organizations existed in a tense relationship with white political control and law enforcement, as they did across much of the South. The Civil Rights Act of 1964 and Voting Rights Act of 1965 had shifted the legal terrain, but law is not the same thing as lived reality. Business owners continued to test the boundaries—sometimes by outright defiance, sometimes by paper-thin claims of private status, membership rules, or “custom.”

The immediate spark for Orangeburg’s protests was a bowling alley—often referenced as All-Star Bowling Lanes—described by multiple accounts as one of the city’s remaining whites-only recreational spaces years after the 1964 act. Students and local residents had long resented the exclusion, not merely because it was illegal, but because it broadcast a blunt message: the law could be passed in Washington, and still be ignored on Russell Street.

What matters here is the ordinariness of the grievance. A bowling alley is not a courthouse or a statehouse; it is leisure, youth, the small rituals of normal life. Segregation’s power was partly in its ability to colonize the ordinary: to decide who could unwind, who could date, who could take up space without permission. When students pressed this point in Orangeburg, they were not simply making a demand about lanes and pins. They were contesting who the city was for.

The student movement arrives: Protest as a form of citizenship

By early February, student activism in Orangeburg had a cadence familiar in civil rights history: entry into a segregated space, confrontation, arrests, and then a widening circle of protest. Accounts vary on specific numbers and sequencing, but the broad outline is consistent. Students attempted to desegregate the bowling alley; police arrested students; the arrests accelerated unrest.

One reason Orangeburg became combustible is that it brought together overlapping identities that the state often found threatening when combined: Blackness, youth, education, and collective action. HBCU students carried a particular symbolic charge in Southern politics. They were simultaneously the beneficiaries of Black institutional life and the agents pushing beyond the incrementalism of older civic leadership. In many towns, local officials treated student protest as an imported contagion, even when the grievances were intensely local. Orangeburg was no exception.

The presence of Cleveland Sellers, then associated with the Student Nonviolent Coordinating Committee (SNCC), became especially important in the official narrative that followed. Sellers was later described by authorities as an agitator; he was also wounded in the shooting and, in the longer arc of the case, became the most visible symbol of how accountability was distributed. Multiple historical accounts emphasize that, in the aftermath, Sellers was the only protester prosecuted and imprisoned in connection with events that culminated in police gunfire.

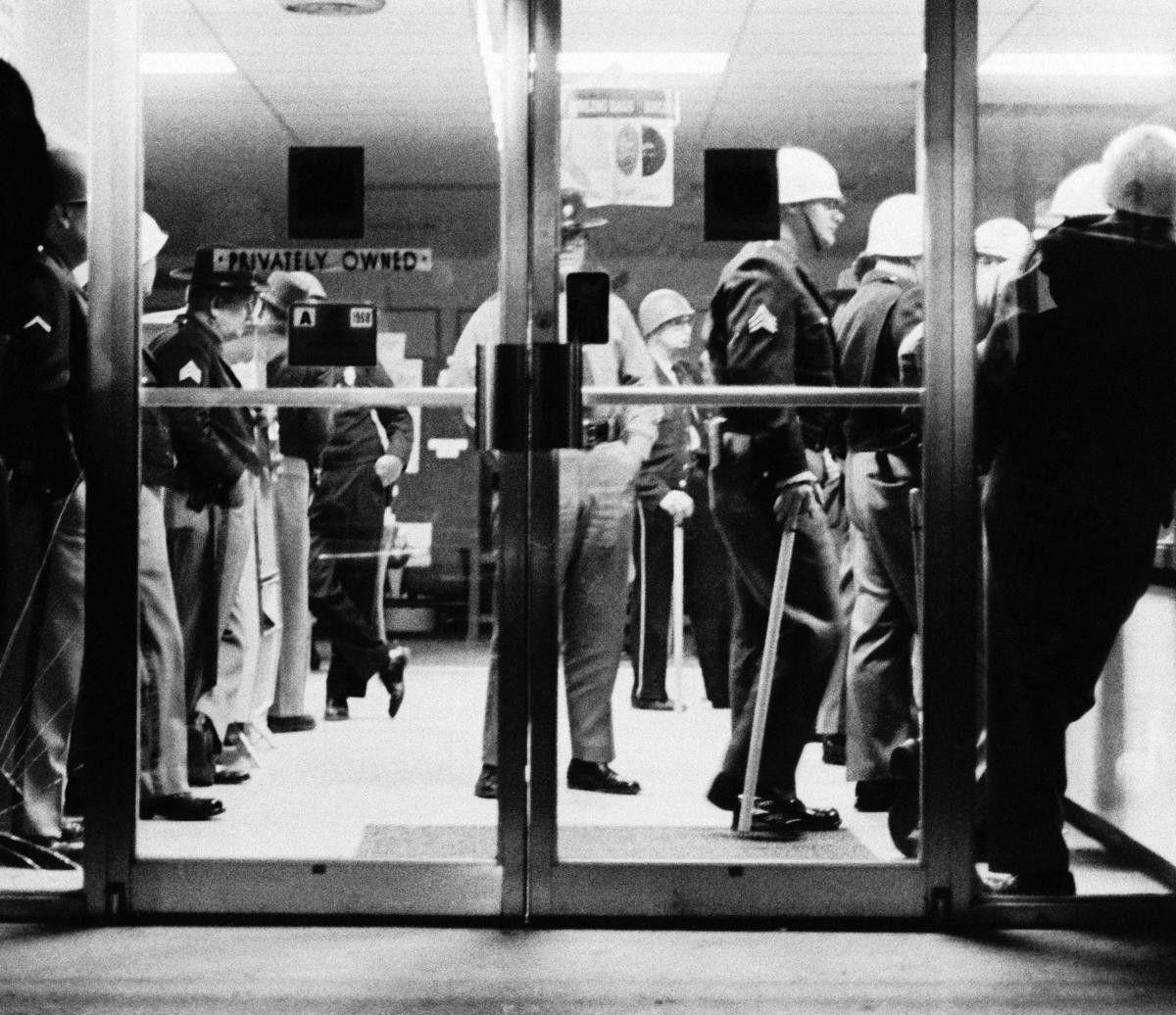

Escalation: The state mobilizes

As tensions rose, the state’s response was not mediation but mobilization. Governor Robert E. McNair ordered a significant law enforcement presence to Orangeburg; National Guard units were deployed. The spectacle of armed state force—troopers with rifles and shotguns, Guard troops in military posture—was meant to communicate control. It also communicated, to students and residents, that the state understood their protest primarily as a security problem.

The imagery matters because it helps explain what happened next. When heavily armed officers confront young protesters in a charged atmosphere, the threshold for perceived threat shrinks. A shouted insult can become “incitement.” A thrown object can become “gunfire.” A crowd can become, in police imagination, a mob. This is not to deny that some protesters may have thrown objects or acted recklessly. It is to recognize that, in such scenes, policing is as much narrative as tactic: officers interpret, and their interpretations can decide who lives.’

By February 8, the campus perimeter had effectively become a staging ground. There were command posts, concentrated police lines, and an environment in which students and troopers watched each other with mutual suspicion.

The night of February 8: Ten seconds that lasted forever

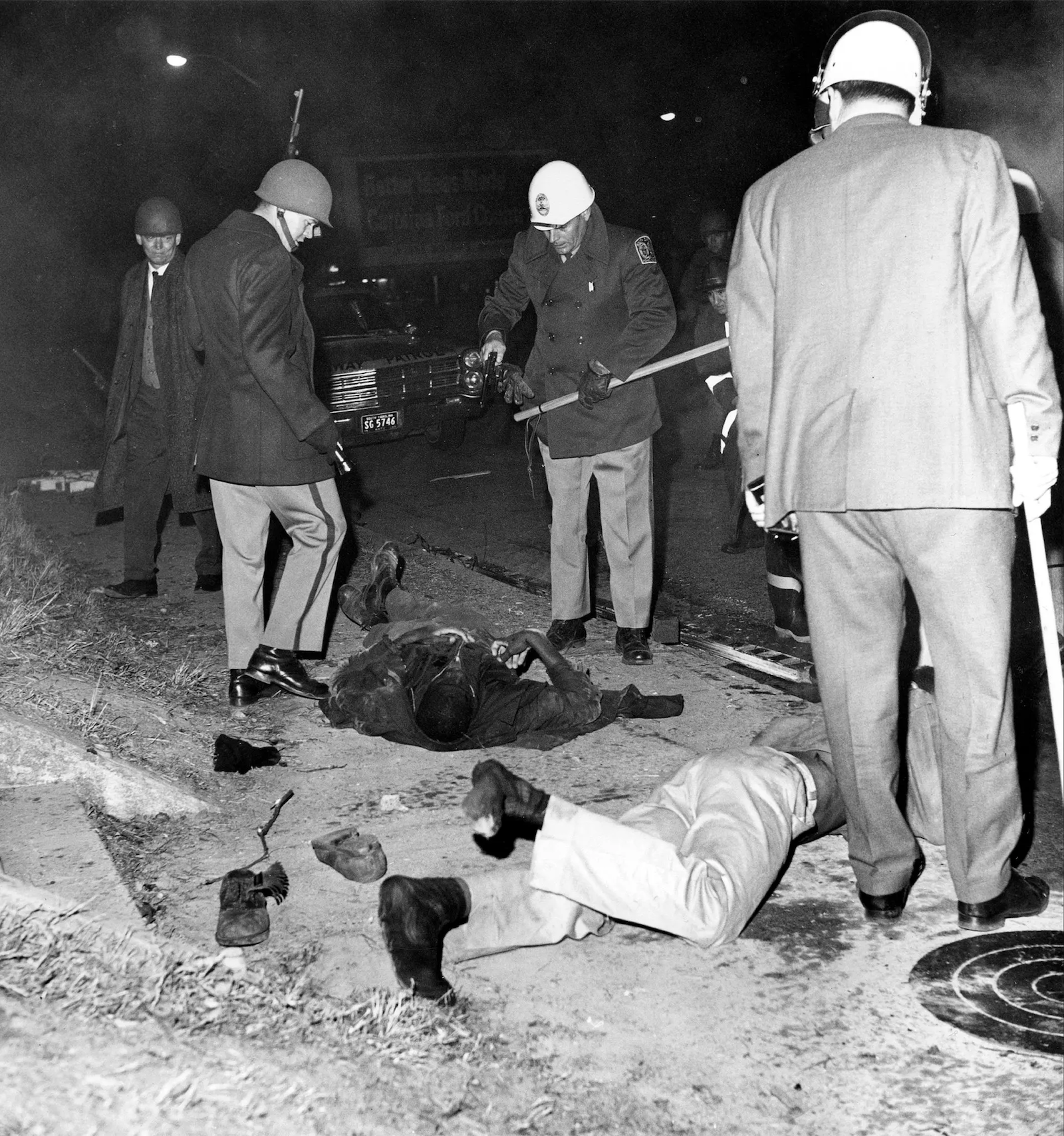

Shortly before the shooting, students had gathered near the campus. A bonfire—variously described as a protest signal, a point of gathering, an act of defiance—burned near the edge of the college grounds. Firefighters arrived; law enforcement was present. In many retellings, an officer was struck by an object thrown from the crowd. Then, without clear warning to disperse—this point is contested but repeatedly raised by survivors and journalists—troopers opened fire.

The volley was brief. That brevity is part of its terror. Survivors have described the gunfire as lasting seconds, yet feeling interminable—a rapid sequence of rifle and shotgun blasts, cutting across bodies that were turning away, running, dropping to the ground. The Washington Post’s 2018 Retropolis account, drawing on interviews including Cleveland Sellers, evokes the sensory memory of the shooting and emphasizes the lethality of the weapons involved, including buckshot.

When the firing stopped, three young Black men would die from their wounds, and dozens were injured. Widely cited summaries note that many were shot in the back while fleeing, a detail that has become central to the moral argument about Orangeburg: whether police were responding to an imminent lethal threat, or unleashing force on retreating students.

The dead had names that should be as familiar as the names from Kent State, but rarely are.

Samuel Hammond Jr. was a student at South Carolina State. Henry Smith was also a student. Delano Middleton was a high school student. The Equal Justice Initiative’s calendar entry underscores their youth and identifies them as Black students killed when white state troopers fired into the crowd.

Even the basic contours of the scene became a contested record. Officials suggested police had been fired upon. Yet a recurring theme in subsequent examinations is that evidence of student gunfire was either absent or deeply disputed; witnesses reported not hearing shots from the crowd before troopers opened fire. The persistence of this dispute is one reason Orangeburg has never settled into the tidy categories that official reports prefer.

Immediate aftermath: Injury, arrest, and the second violence

Mass shootings generate two kinds of trauma: the immediate physical harm and the social decisions that follow—how victims are treated, how information is managed, how blame is assigned. In Orangeburg, the aftermath carried its own cruelties. Students were transported for medical care in a segregated environment. Accounts preserved by historical projects describe hostility and mistreatment at the hospital and aggressive policing in the hours after the shooting.

That same night, law enforcement began arresting individuals connected to the protests, and the state’s narrative quickly moved to criminality: riot, arson, disorder. Cleveland Sellers—wounded and seeking treatment—was arrested and later faced a raft of charges, becoming, as one oral history summary puts it, the only person charged and arrested in connection with the massacre itself.

If the first violence was the gunfire, the second was the rapid construction of a story in which the dead and wounded were also culpable. This pattern is familiar in American protest policing: after lethal state force, institutions often seek justification through retroactive criminalization of the crowd. The mechanism is not subtle. It works because it shifts the moral center of the story from state action to protester behavior, and because it anticipates what will matter most in court: not the full social context, but the narrow question of whether officers can claim fear.

The legal record: Acquittals, convictions, and the question of “justice”

One of the enduring shocks of Orangeburg is not only that police killed students, but that accountability ran in reverse. In federal court, nine officers were tried and acquitted. Meanwhile Sellers was convicted in state court on riot-related charges tied to the broader unrest. In later years, he received a full pardon.

This asymmetry did lasting damage. It told the community that state violence could be legally vindicated, while protest could be criminally punished, even when protest was aimed at enforcing federal civil rights law. It also hardened a civic lesson that still shapes how communities assess policing: that “due process” and “justice” can be radically different experiences, depending on who is on trial.

The Orangeburg case also illustrates the structural obstacles to revisiting civil rights-era crimes. A later FBI review did not lead to charges, in part because the officers had already been acquitted—raising double jeopardy barriers—and because time collapses the evidence required for prosecution. In the broader context of civil rights cold cases, Orangeburg has appeared in discussions about unsolved or unresolved cases from the era. A 2007 congressional report on unsolved civil rights crimes cited the 1968 “Orangeburg Massacre” as an example of a case in which state police shot and killed student protesters.

When the Department of Justice and affiliated initiatives revisit civil rights-era killings, they often arrive at the same cliff edge: moral clarity without a prosecutable path. That reality does not absolve; it reveals how the legal system can be structured to allow violence to become history before it becomes accountability.

Why Orangeburg didn’t become “the” national campus shooting

Orangeburg is frequently described as less remembered than Kent State. The comparison is not simply about race, though race is inseparable from it. It is also about the mechanics of attention: timing, imagery, and the political legibility of victims.

The Lowcountry Digital History Initiative notes factors that plausibly shaped media impact, including that the massacre occurred at night—limiting photographs that could circulate widely—and that it was soon overshadowed by other seismic events of the era..

There is also the uncomfortable truth, voiced in many retrospectives, that the nation’s capacity for identification has often tracked whiteness. Kent State presented white, middle-class students as victims of state violence; Orangeburg presented Black students at an HBCU. One became a staple of American civic mourning; the other became a regional trauma with periodic anniversary coverage.

The Washington Post’s historical reporting frames Orangeburg explicitly as a tragedy that “barely made national news,” underscoring how the massacre’s victims and setting were treated as marginal to the national narrative of protest-era violence.

To say this is not to argue that Kent State was over-remembered; it is to argue that Orangeburg was under-remembered, and that the imbalance is instructive. A nation that remembers selectively does not merely misplace the past—it trains itself for the future.

The people who carried the story when institutions wouldn’t

Orangeburg survived in memory because survivors, families, and local institutions insisted on ritual: commemorations, memorials, teaching, and testimony.

South Carolina State University has maintained an annual commemoration and built physical memorials honoring the dead. The university’s commemoration materials emphasize the names—Smith, Hammond, Middleton—and the institutional commitment to remembrance through ceremonies and awards.

Local journalists, historians, and photographers also helped keep Orangeburg visible. Cecil Williams, a civil rights photographer based in Orangeburg, has spoken repeatedly about documenting the movement and the massacre’s legacy, including through his museum and public talks. Claflin University coverage of Williams’ recollections points to the way local custodians of memory—people who held cameras, notebooks, and archives—became a counterweight to official forgetting.

Documentary work has played a similar role. Scarred Justice: The Orangeburg Massacre, 1968 is frequently cited as a film that sought to bring the story into broader public view decades later, framing the massacre as both tragedy and deliberate denial.

And then there are the oral histories—survivors and participants returning, again and again, to the crucial details: where they stood, what they heard, how they ran, how the aftermath felt. The South Carolina Oral History Collection’s entry on Cleveland Sellers, for example, foregrounds the fact that he was the only person charged in the massacre’s wake, an encapsulation of how the state tried to assign responsibility.

These forms of memory matter because they are not merely sentimental. They are evidentiary. When institutions fail to produce accountability, remembrance becomes a civic practice: a way of insisting that a community’s lived record is not inferior to the state’s paperwork.

Orangeburg and the architecture of “white supremacist justice”

In popular memory, “injustice” can sound like an abstract moral category. Orangeburg makes it concrete.

Consider the narrative structure that unfolded: Black students protest a segregated business after federal law has nominally ended such discrimination; the state responds with armed force; the state kills students; the state prosecutes a protest leader; officers are acquitted; the community is told, implicitly, to accept the verdict as closure. Years later, the man prosecuted receives a pardon—an admission, at minimum, that the earlier conviction cannot be defended as clean justice.

This is why Orangeburg continues to appear in Black commentary about South Carolina’s political and racial history, and why it surfaces in national discussions about civil rights-era crimes and modern policing. In these framings, Orangeburg is not simply “something that happened.” It is a case study in how the state narrates itself, and how that narration can be weaponized.

The Root, in a 2024 piece that contextualizes historic Black student protests, describes the Orangeburg Massacre as one of the most violent moments of the civil rights movement, emphasizing the peaceful protest against a whites-only bowling alley and the lethal police response.

The point is not that every participant was saintly or that every moment was orderly. The point is that the state’s use of lethal force—and its later allocation of criminal liability—fit a long pattern in which Black protest was treated as presumptively criminal and white or state violence as presumptively defensive.

The massacre as a hinge: From civil rights to “law and order”

The late 1960s were not only a peak of civil rights organizing; they were also the moment when “law and order” became a dominant political language, often coded and deployed against Black freedom movements. Orangeburg sits at that hinge. Officials could frame the students as a riotous threat, presenting armed response as necessity rather than choice. The politics of that framing reverberate forward into modern debates about protest, policing, and the definition of “public safety.”

One reason Orangeburg remains so instructive is that it shows how quickly the language of safety can be mobilized to justify extraordinary violence against ordinary demands. “Let us bowl” is, on its face, a modest request. When the state meets such a request with rifles, what is being defended is not safety. It is hierarchy.

What “closure” looks like when the dead are not vindicated

Even now, accounts of Orangeburg often include a note of incompletion: details disputed, accountability unresolved, national recognition partial.

Major institutions have taken steps toward acknowledgment. South Carolina State University has continued commemorations and memorial projects; public figures have issued statements of regret over the years; national outlets periodically return to the story on anniversaries.

But closure, in the deeper sense, has been elusive for reasons that are structural, not psychological. The acquittals foreclosed criminal accountability. Time foreclosed many other legal paths. What remained was the work of history—and history moves at the speed of archives, classrooms, and public rituals.

PBS’ Un(re)solved project includes an interactive case page for Henry Smith that situates Orangeburg within the universe of civil rights-era killings that remain, in some legal or moral sense, unresolved.

That framing matters. It reminds us that unresolved does not always mean “unknown.” It can mean something harsher: known, and yet institutionally unremedied.

The significance of Orangeburg now: what it teaches a country still arguing about protest

Orangeburg is not only a story about 1968. It is a story about the recurring American question: how does the state respond when marginalized people attempt to make the law real?

In the decades since, Americans have watched other confrontations between protest and police power—on bridges, outside courthouses, in city squares, on campuses. Each time, the same arguments reappear: Were the protesters peaceful? Did someone throw something? Did police fear for their lives? Was the response proportional? Orangeburg offers a grim template for how those questions can be answered in ways that privilege state authority over civilian life.

It also offers a warning about visibility. The LDHI observation that night limited photographs is not a trivial media critique; it points to a structural truth. In a society where images drive empathy, the absence of images can become an absence of accountability.

And it offers a warning about canon-making. When a nation chooses one massacre to symbolize state overreach and leaves another in semi-obscurity, it is not simply misremembering. It is defining whose vulnerability counts as “unthinkable.”

Returning to the names

The simplest ethical act, in a story like this, is to repeat what can be too easily lost: the victims were not abstractions.

Samuel Hammond Jr. Henry Smith. Delano Middleton.

They were young. They were Black. They were in the orbit of an HBCU campus where students were asserting a straightforward claim to equal citizenship. They were killed when state troopers fired into a crowd.

Orangeburg’s significance is inseparable from that fact. It is a massacre of students; it is a case about policing; it is a lesson about memory; it is a map of how power protects itself.

And it is, still, a measure of the country’s honesty. Not because Orangeburg can be made to stand in for every injustice, but because it forces a question that is both historical and contemporary: if this happened—if the state killed students in seconds and escaped accountability—what else have we normalized by allowing it to fade?

More great stories

Gloria Blackwell: Miss Movement