Insisting—again and again—that imagination is not the opposite of reality. It’s one of the ways we build it.

Insisting—again and again—that imagination is not the opposite of reality. It’s one of the ways we build it.

By KOLUMN Magazine

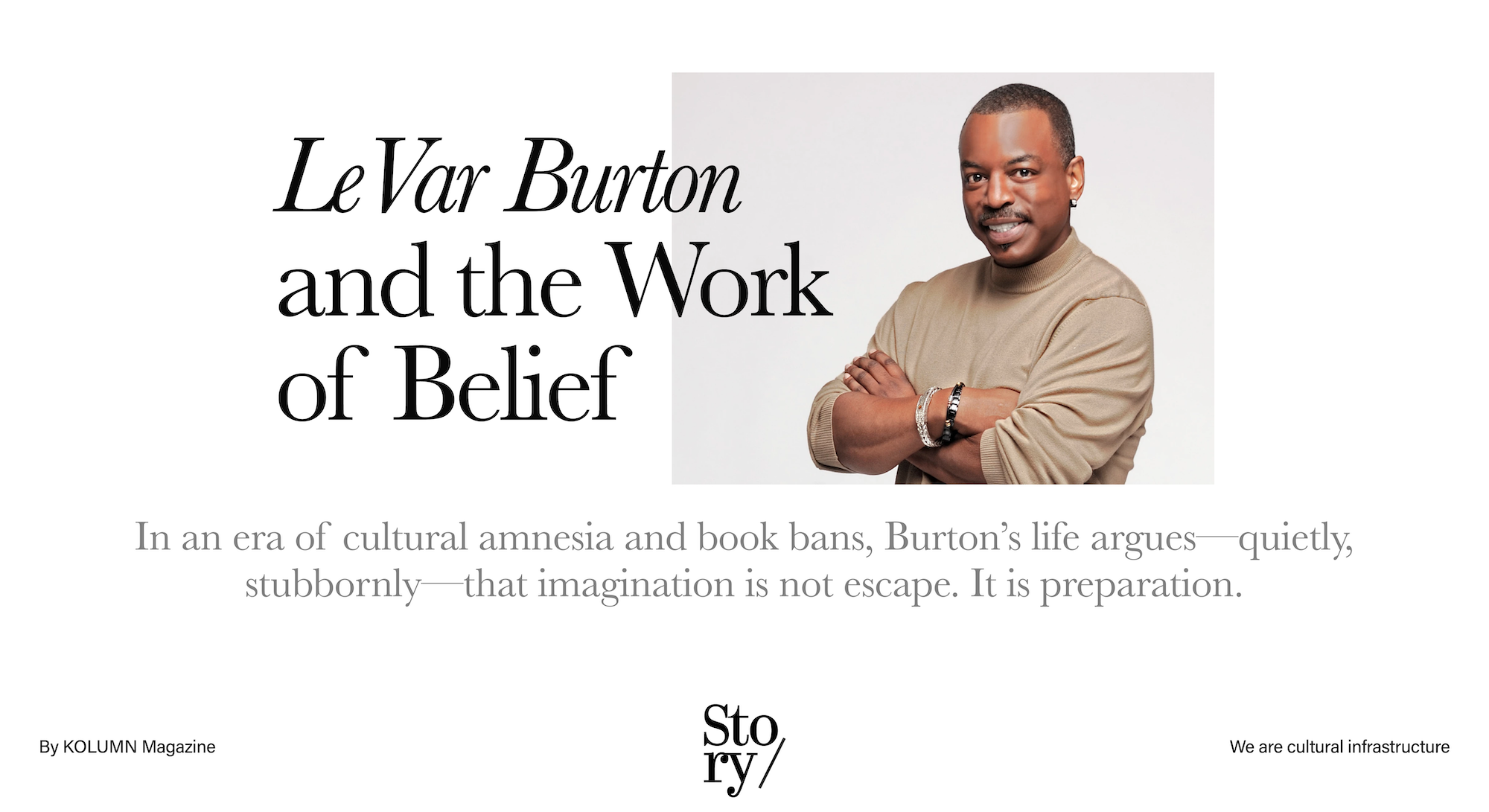

There are celebrities whose fame is primarily a matter of recognition—faces you know, voices you can place, roles you can summarize in a sentence. And then there are the rarer figures whose celebrity operates as something closer to civic infrastructure. You don’t only know them; you’ve been shaped by them. They are part of how you learned to be a person in public, how you learned to think, how you learned to read your way out of whatever room you were born into.

LeVar Burton is one of those figures.

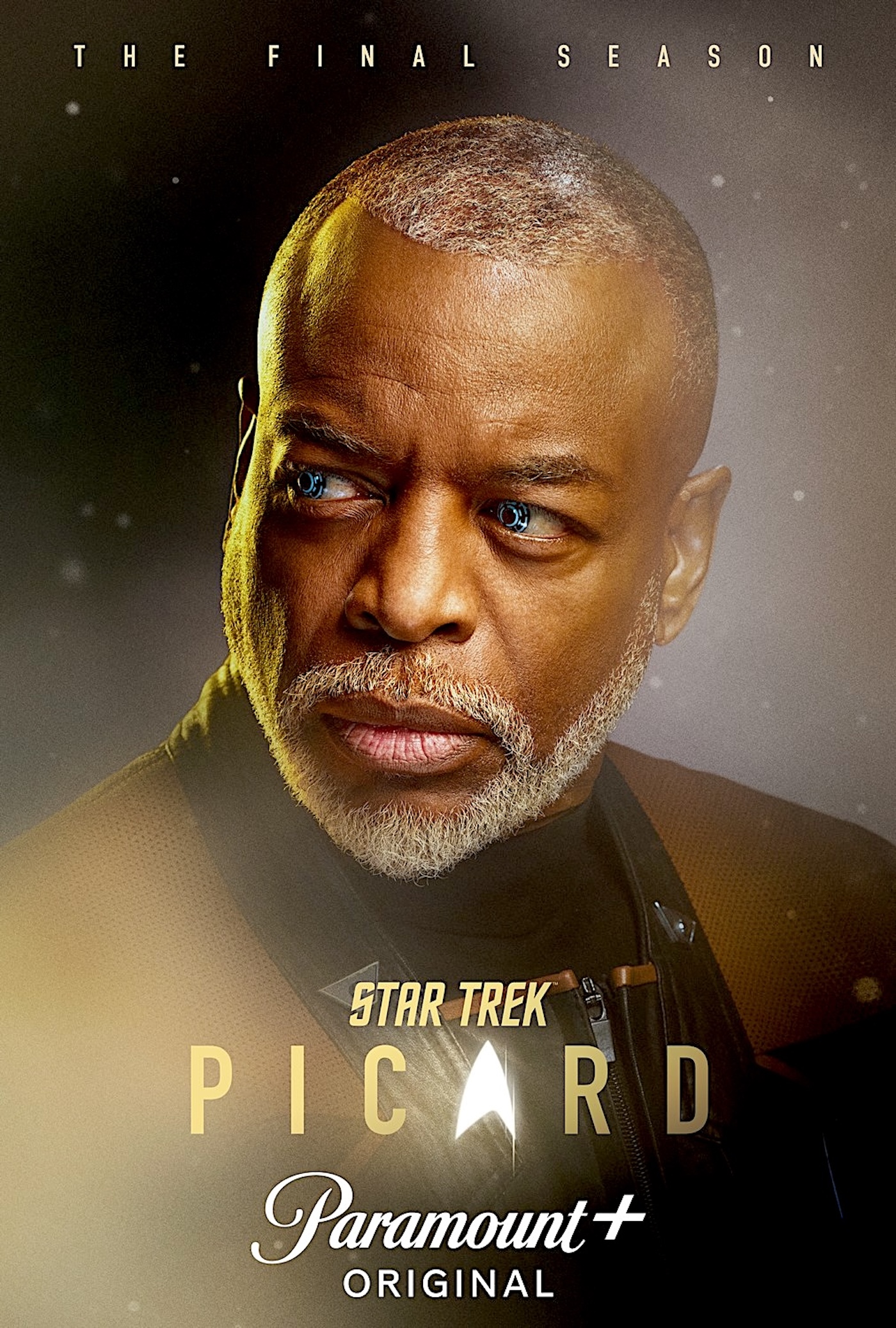

If you grew up in the United States at almost any point in the last half-century, it’s possible Burton entered your life in one of three primary forms: as Kunta Kinte—young, terrified, defiant—inside the national event television of Roots; as Geordi La Forge, the starship engineer whose competence was a kind of moral steadiness on Star Trek: The Next Generation; or as the warmly insistent host of Reading Rainbow, who looked straight into the camera and treated children not as future adults but as present-tense citizens. Each role has its own mythology, its own fan culture, its own afterlife. Together, they create something else: a biography that doubles as an argument about what American popular culture can do when it is purposeful.

Burton’s significance is not simply that he has enjoyed a long career across television, film, and new media. It’s that he has repeatedly occupied roles that ask the country to reckon with itself—its history, its fantasies, and its responsibilities—and then, in a second move, he has tried to turn that reckoning into a practice: read more, learn more, widen your empathy, test your assumptions, imagine better.

The fact that this argument is delivered through entertainment is not incidental. Burton’s genius has always been a kind of translation: taking large, frightening, abstract national questions—What did slavery do to us? What does a multiracial future require? What is literacy for?—and rendering them intimate enough for families, classrooms, and living rooms. He has made the work of becoming informed feel less like a chore than a privilege. He has made curiosity feel like belonging.

To understand how Burton became this sort of figure, you have to track the interplay between performance and pedagogy that runs through his life. You also have to take seriously the way audiences have used him. Burton is an actor, yes—but he is also a repository of collective memory. For millions, he is the face attached to first lessons: how to pronounce unfamiliar words, how to treat knowledge as pleasure, how to imagine Blackness outside the constraints of stereotype, how to situate yourself in a longer story than your neighborhood, your school, your own immediate circumstance.

That is not an easy burden. Burton has carried it with a steadiness that looks, from the outside, like ease. In truth, the steadiness is part of the work.

A childhood split between worlds

Levardis Robert Martyn Burton Jr. was born on February 16, 1957, in Landstuhl, in what was then West Germany, and raised primarily in the United States. His mother, as Burton has recounted across multiple interviews over the years, played a central role in cultivating the values that would later define his public persona: faith, discipline, and the idea that education is not a luxury but a lifeline. The details of Burton’s early life matter not because they offer some simplistic “origin story,” but because they help explain a particular kind of ambition—the ambition to do work that is both visible and useful.

In a culture that often tries to separate artistry from service, Burton has consistently refused the distinction. Even his career’s most glamorous chapter—science fiction stardom—has been tethered to a kind of ethics: competence, compassion, collective problem-solving. His most explicitly educational chapter—Reading Rainbow—has always been, at heart, a performance about desire: desire to know, to explore, to meet the world with open eyes.

This blend did not emerge by accident. Burton’s public comments about his youth have suggested a boyhood shaped by institutional structures—school, church—and by a sense that the world had to be engaged deliberately, with attention. In one widely circulated recollection, Burton has spoken about seriously considering the priesthood before acting, a fork in the road that speaks to the moral intensity he brings to his work even now. In that telling, the vocation wasn’t fame; it was purpose.

When Burton moved toward acting, it wasn’t a rejection of purpose so much as a shift in method. Performance offered a different kind of pulpit.

Roots and the shock of history on prime-time television

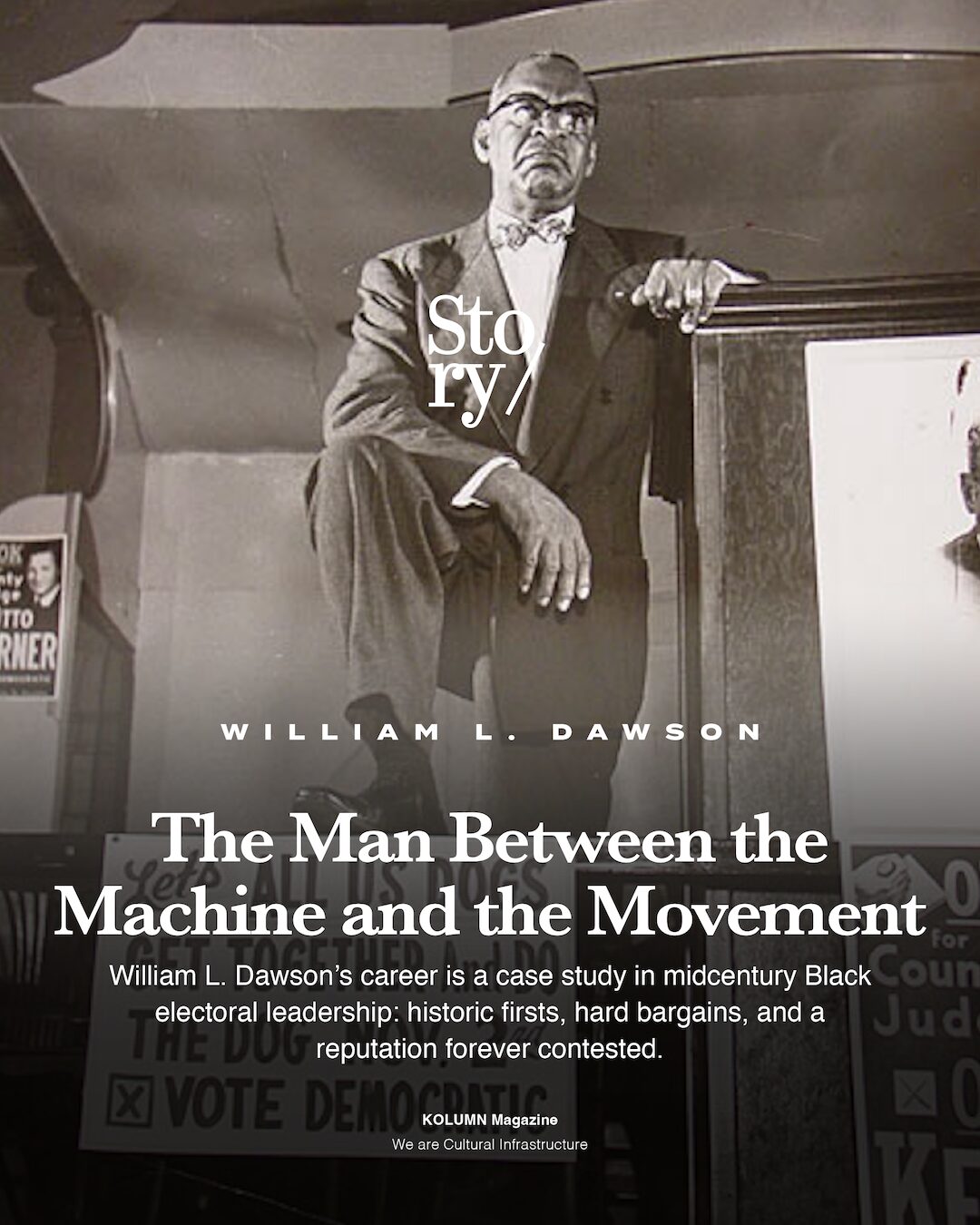

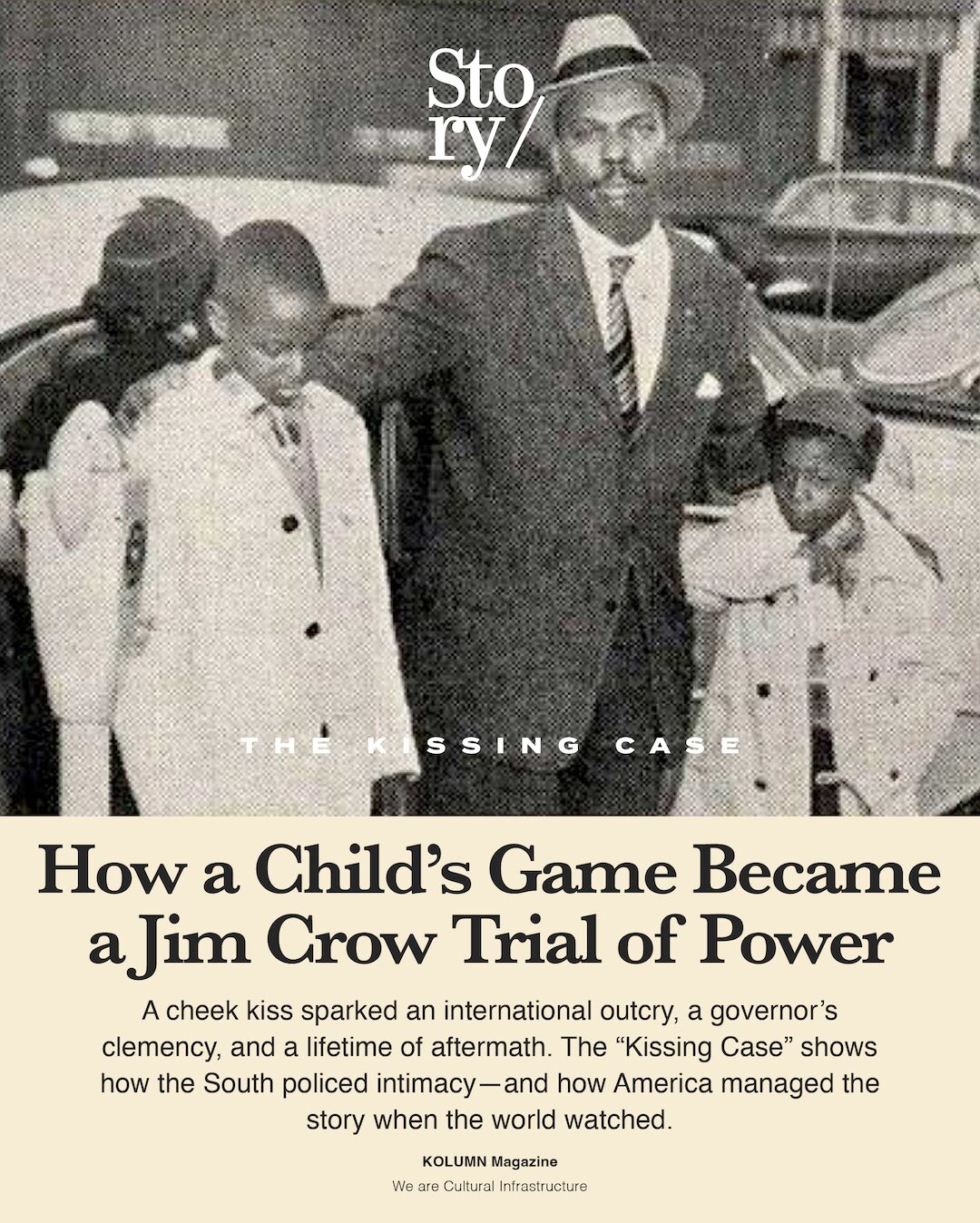

In 1977, Roots arrived as a national event, and Burton—still very young—became its face. The miniseries, adapted from Alex Haley’s book, dramatized the capture and enslavement of an African teenager and traced generations of a Black family in America. Burton played Kunta Kinte with a rawness that made the story difficult to compartmentalize. The narrative demanded attention; his performance demanded witness.

The Television Academy’s retrospective on Burton emphasizes the scale of the phenomenon: the miniseries drew an estimated 130 million viewers and helped make Burton instantly famous, earning him an Emmy nomination. The Washington Post, reflecting on Roots in later years, has also noted that the production became a rare high-profile dramatic outlet for Black actors and that it placed itself among the most-watched programs in U.S. television history.

For a young actor, the success of Roots could have become a trap: a single defining role, a lifetime of being introduced as “the guy from Roots.” For Burton, it became something else—an early lesson in how mass media can function as national curriculum. Roots didn’t just entertain; it educated, provoked, and, for many Americans, forced a confrontation with slavery’s lived reality. Burton’s face, in that context, was not merely a character’s face; it was an emblem of a history many viewers had been trained to minimize.

That mattered for Black audiences, certainly. It also mattered for the country at large, because Roots suggested that a mainstream audience could be asked to sit with Black pain without being offered easy release. Burton’s performance, especially, carried a kind of moral insistence: you will look at this, you will not look away.

It’s hard to overstate the importance of this moment in the late-1970s television landscape. Prime-time network television was a dominant national hearth, and Roots turned that hearth into a site of historical reckoning. Burton was, in effect, drafted into the work of memory.

And then, crucially, he kept going.

A future-facing Blackness: Geordi La Forge and the politics of competence

A decade later, Burton joined Star Trek: The Next Generation as Lieutenant Commander Geordi La Forge, the Enterprise’s chief engineer—a character defined not by exceptional violence, nor by comedic sidekick energy, but by intelligence, technical mastery, and emotional loyalty. The show ran from 1987 to 1994, and Burton’s presence helped normalize a vision of the future in which Blackness is neither erased nor reduced.

In the cultural grammar of American entertainment, this matters. Representation debates often focus on visibility—who appears on screen, how often, in what kinds of roles. But Burton’s significance is not only that he appeared. It’s what he embodied: a Black man trusted with the ship’s infrastructure, trusted with the systems that keep everyone alive. The character’s authority is not symbolic; it is operational.

Geordi’s visor—used because the character is blind—became its own iconography, but what the visor really signaled was a larger theme: disability not as deficiency but as a site of adaptation and skill. Geordi was allowed to be vulnerable, awkward, tender, frustrated—an entire human being—without losing his authority. In a genre that can drift toward archetype, Burton helped keep the character grounded.

If Roots tethered Burton to America’s past, Star Trek tethered him to a future that asked the country to imagine itself better than it had been. And if Roots demanded witness, Star Trek offered practice: practice at seeing a Black man as indispensable, as normal, as part of “we.”

This is one of Burton’s quietest achievements: he has been part of teaching multiple generations what “we” can look like.

Reading Rainbow and the gentle revolution of literacy

Then came the role that Burton himself has repeatedly identified as his proudest: Reading Rainbow.

The show premiered nationally in July 1983 with Burton as host and an executive producer, and it would run for decades, shaping the reading habits—and the emotional relationship to reading—of millions of children. The Library of Congress, in a biographical note connected to Burton’s participation in its programming, summarizes the scale of recognition: Burton’s work on Reading Rainbow brought him multiple Daytime Emmy Awards, NAACP Image Awards, and a Peabody Award.

But awards don’t capture what the show did.

What Reading Rainbow offered was a model of literacy that was not punitive. It did not treat reading as a test you pass to prove you are smart. It treated reading as a door. The show’s structure—book-centered episodes paired with “field trips” into the world—suggested that text and life are not separate realms. Books are not just assignments; they are maps. Burton’s hosting style made that philosophy feel personal. He didn’t talk down to children. He invited them in.

The signature line—“But you don’t have to take my word for it”—was more than a catchphrase. It was epistemology, delivered with a smile. Don’t believe because an authority told you. Verify. Explore. Read for yourself. The line quietly trains skepticism in the best sense: not cynicism, but the habit of seeking evidence, of treating knowledge as something you can pursue directly.

In a country that often confuses education with credentialing, Burton modeled education as intimacy with the world.

The National Endowment for the Humanities, in a profile connected to Burton’s receipt of the National Humanities Medal, includes a striking exchange: asked what he is proudest of, Burton answers that while many would assume Roots because of its magnitude, for him it is Reading Rainbow—the impact on the reading habits of generations. The choice is revealing. Burton recognizes that the deepest form of cultural power is not fame. It’s habit formation. It’s shaping what people do when no one is watching.

If Roots forced America to look at history, Reading Rainbow tried to give children tools to change what came next.

Authenticity as a negotiation, not a vibe

One reason Burton’s hosting has remained so resonant is that it reads as authentic. But “authenticity,” in Black public life, is rarely a simple personal quality. It is often a negotiation—a set of decisions made under scrutiny.

Recent reporting around the documentary Butterfly in the Sky—which revisits the cultural impact of Reading Rainbow—underscored that Burton’s on-screen presence was not always welcomed in its fullness by the adults around him. The Root reported in 2024 that Burton has described moments when producers attempted to restrain aspects of his “Black style,” and that he fought to maintain his authenticity. PEOPLE’s coverage of the documentary similarly emphasizes that Burton insisted on “being himself” on camera, and that this insistence was part of the show’s power for viewers who rarely saw a Black adult centered as trustworthy and joyful in children’s media.

That fight matters. It means that the warmth audiences remember was not merely a personality trait—it was a creative stance, protected and asserted in real time. Burton’s gentleness was not submission. It was chosen. His visibility was not accidental. It was defended.

There is a tendency to treat beloved children’s television as politically neutral, as if it floats above power. In reality, the question of who gets to guide children—who gets to be the face of learning, curiosity, and moral authority—is profoundly political. Burton’s presence on public television, episode after episode, was a slow, steady disruption of the idea that whiteness is the default face of education.

That disruption didn’t arrive with a manifesto. It arrived with a book.

Reinventing a legacy for the digital age

When the original series ended in 2006, Burton did not treat it as a nostalgia artifact. He treated it as a platform that had to evolve with the media ecosystem children actually inhabit. After the show left the air, Burton and his business partner acquired rights associated with the brand and worked to reimagine it through new formats.

The Atlantic’s early coverage of the Reading Rainbow iPad app in 2012 captured the logic of the transition: the app offered a digital library model and small elements of gamification, presenting reading as interactive without letting it become purely transactional. The cultural conversation around this reinvention quickly expanded into debates about public goods: if Reading Rainbow was a public television staple, what did it mean for its next iteration to require private funding or subscription models?

In 2014, Burton launched a widely publicized Kickstarter campaign to revive Reading Rainbow in a web-based form. The Guardian’s reporting on the campaign and its aftermath documents both the scale of public enthusiasm and the philanthropic ambitions attached to it, including the idea of making classroom access broadly available. The Washington Post, covering the Kickstarter at launch, framed it as a major effort by Burton to bring the brand back online. Ebony also covered the early surge of support, emphasizing the speed with which the campaign hit its initial fundraising goal.

This period matters because it shows Burton’s willingness to put his reputation on the line for a cause that, in purely entertainment terms, might have seemed quaint. Crowdfunding a literacy project is not the standard arc for an actor with sci-fi credentials and a beloved back catalog. Burton did it anyway, and in doing so he revealed something essential about his approach to fame: he spends it.

In the economics of celebrity, attention is currency. Burton has repeatedly used that currency to subsidize reading.

Reading aloud to adults, and the expansion of the brand “LeVar Burton”

In 2017, Burton launched LeVar Burton Reads, a podcast built around the simple pleasure of being read to—short fiction delivered with the same voice that guided childhood afternoons, now aimed at adult listeners. The concept is almost disarmingly direct: stories, performed with care, offered as an antidote to the distracted pace of modern life.

The show earned major recognition. It won NAACP Image Award honors in podcast categories, with coverage from outlets including BET and Variety. It also won Webby Awards in podcast categories, with official Webby listings documenting the honors.

What’s notable here isn’t only the awards; it’s the continuity. Burton found a way to translate the emotional experience of Reading Rainbow—the sense that a story can change the room you’re in—into a form that meets adults where they are now: headphones, commutes, evenings when attention feels fractured. He turned the voice into a medium.

Even the popular shorthand—“Reading Rainbow for adults”—reflects the cultural position Burton occupies: he is not merely a performer but a container for a certain feeling about learning. He has become, for many, an emblem of the moment when reading first felt like joy rather than obligation.

Honors that clarify the real work

In October 2024, Burton received the National Humanities Medal as a 2023 medalist, with the National Endowment for the Humanities listing him explicitly among the honorees. This is the kind of award that can easily read as ceremonial—another line in a biography. But in Burton’s case, it clarifies what the culture has long understood about him: his primary contribution is not only artistic. It’s civic.

The medal is given for work that deepens public engagement with the humanities—history, literature, philosophy, the fields that help a society interpret itself. Burton’s career is an argument that television and digital media can, at their best, serve those fields rather than diminish them. The Associated Press coverage of the 2024 White House medals ceremony situates the event within broader cultural anxieties about whose stories are valued and protected. Burton’s presence in that cohort is meaningful: it places literacy advocacy alongside more traditionally recognized “high culture” achievements.

This recognition also arrives in a moment when reading itself has become politicized in new ways—through book banning campaigns, attacks on curricula, and attempts to narrow what young people are allowed to know. Burton has been publicly aligned with pro-reading, anti-censorship efforts in ways that make his long-standing message newly urgent. Entertainment Weekly’s reporting on Burton hosting the National Book Awards in a politically charged moment for literature underscores that his public identity is now tied not only to reading as pleasure, but reading as freedom.

He has, in effect, become an ambassador not only for books, but for access to books.

A recurring theme: Burton as the trusted guide

Across Burton’s career, a pattern emerges. He is repeatedly cast—by producers and by audiences—as a guide. In Roots, he guides viewers into the terror and resilience of enslaved life. In Star Trek, he guides viewers through a future that asks for cooperation and competence. In Reading Rainbow, he guides children through the emotional geography of books. In the podcast era, he guides adults back toward attention.

This is not simply a product of Burton’s demeanor. It’s a cultural role he has cultivated: trustworthy narrator, steady witness, warm teacher, curious companion. Trust is not a neutral commodity in American public life; it is distributed unevenly, withheld from some groups and granted reflexively to others. Burton’s career represents a sustained challenge to that distribution. He has been trusted by millions of families with the mental and moral formation of their children.

That trust has consequences. It means that Burton’s image becomes shorthand for a set of values: kindness, curiosity, rigor, the belief that education is not about domination but expansion. It also means Burton is often pulled into public conversations at moments when those values feel threatened.

When Reading Rainbow returned in a new digital form with a new host, coverage emphasized how Burton’s legacy inspired the next generation of literacy advocates. The Associated Press, reporting on the reboot, highlighted how the new host was influenced by Burton’s example. Word In Black, covering cultural “good things” impacting Black kids, also framed Burton as the original face of the show’s “magazine-style” format and a foundational model of on-screen encouragement.

The throughline is clear: Burton is not just remembered. He is inherited.

The quieter chapters: Directing, producing, and building work behind the camera

A full accounting of Burton’s accomplishments also includes his work behind the scenes—directing television episodes and producing projects that align with his broader commitments. This dimension is less visible to the public, but it helps explain Burton’s durability. He has never relied exclusively on being cast. He has built capacities: directing, producing, shaping media rather than only starring in it.

This matters especially for Black artists in Hollywood, whose careers have often been constrained by gatekeeping. Burton’s pivot toward production and direction reflects an understanding of how power works in entertainment: it isn’t only in performance; it’s in decision-making.

The details of Burton’s directing work appear across archival coverage and entertainment databases, but the larger point is strategic: he has sought leverage. He has wanted to be in the rooms where projects are shaped, where values are translated into scripts, budgets, and creative choices.

Why Burton still matters now

It’s tempting to treat Burton’s cultural significance as nostalgic—something that belongs to the childhoods of Gen X, millennials, and anyone else who remembers the texture of public television. But nostalgia, in Burton’s case, is not the point. The point is that the values he has represented are newly contested.

The United States is living through an era when the meaning of education is under direct pressure: attacks on libraries, restrictions on what teachers can say, ideological policing of history, and a broader economic context that makes sustained attention feel like a luxury. In that environment, Burton’s message—read, verify, imagine, expand—sounds less like a slogan and more like a survival strategy.

Burton’s career also offers a model for what “positive representation” can look like when it is not shallow. He has not been significant because he played perfect characters or because his on-screen presence was universally comfortable. He has been significant because he kept insisting on a vision of Black life that includes intellect, tenderness, curiosity, and authority. He made those qualities visible, ordinary, desirable.

And he did so without abandoning complexity. Roots is not comfortable. The legacy of slavery is not a feel-good brand. Burton’s early fame is tethered to a story that continues to haunt the country, and his later fame is tethered to the work of trying to give children tools to face that haunting with more knowledge than their predecessors had.

In other words: Burton has built a career on the idea that stories matter because they change what people can imagine. And what people can imagine changes what people will tolerate.

The measure of a life: Impact that outlasts the screen

A common way to describe Burton is “beloved.” The word is accurate, but it can also diminish the rigor of what he has done. Belovedness suggests softness, sentiment, an easy warmth. Burton’s belovedness is, in fact, a kind of hard-won cultural authority.

To be beloved across decades, across genres, across generations, is not simply to be charming. It is to be reliable. It is to deliver something people need in changing forms: in the 1970s, a mirror held up to history; in the late-1980s and early-1990s, a Black futurity grounded in competence; in the 1980s through 2000s, an education ethic packaged as adventure; in the podcast era, a return to attention as a human practice; in the 2020s, a public stance that reading is not merely personal enrichment but social necessity.

Recognition like the National Humanities Medal functions, here, as a kind of official confirmation of what audiences already knew: Burton’s work has been part of the country’s humanities education, whether the country named it that way or not.

Burton’s story also helps clarify a broader truth about American culture: sometimes the most transformative figures are not those who dominate headlines, but those who quietly shape daily habits. Burton has shaped the habit of reading. That is an impact measured not only in awards but in bedtime routines, library cards, classroom corners, and the private moment when a child realizes that a book can take them somewhere else—and that “somewhere else” can change the meaning of “here.”

He has made that realization feel possible for millions.

And he has done it while carrying the weight of history, refusing cynicism, and insisting—again and again—that imagination is not the opposite of reality. It’s one of the ways we build it.

More great stories

Camera as a Passport