Dawson’s activism was managerial, bureaucratic, and deeply local. It was the activism of building a durable organization and using it, year after year, to extract resources from a political system that rarely gave them away.

Dawson’s activism was managerial, bureaucratic, and deeply local. It was the activism of building a durable organization and using it, year after year, to extract resources from a political system that rarely gave them away.

By KOLUMN Magazine

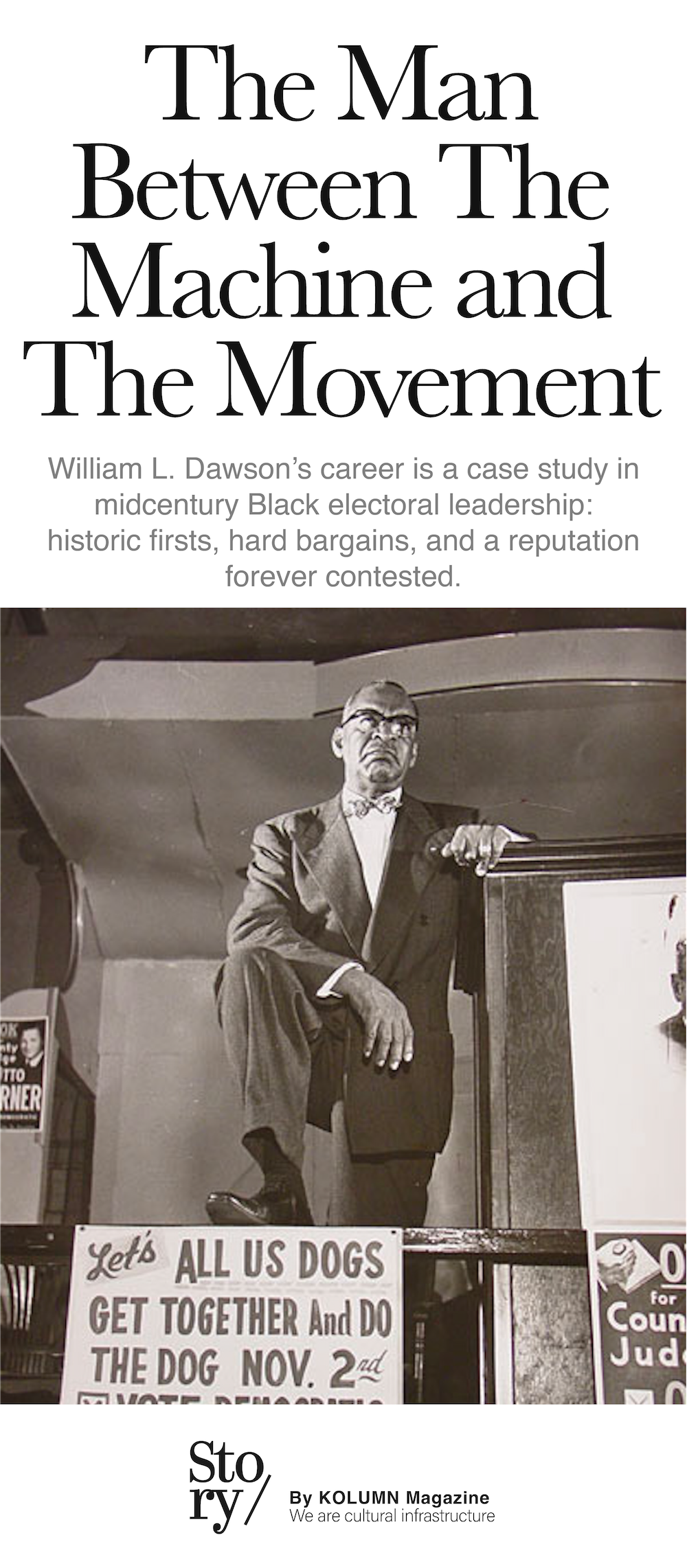

In the political folklore of Chicago, there are mayors who loom like skyline architecture, precinct captains who move like invisible currents, and ward organizations that feel less like committees than weather systems—permanent, moody, capable of deciding who eats and who waits. William L. Dawson learned early that in such a city, morality could be a compass and still be inadequate for navigation. He believed, with the conviction of a man shaped by the Jim Crow South and tempered by the transactional North, that power was not an abstraction. It was a payroll. It was a permit. It was a phone call returned. It was a seat at a table where decisions were made before the meeting began.

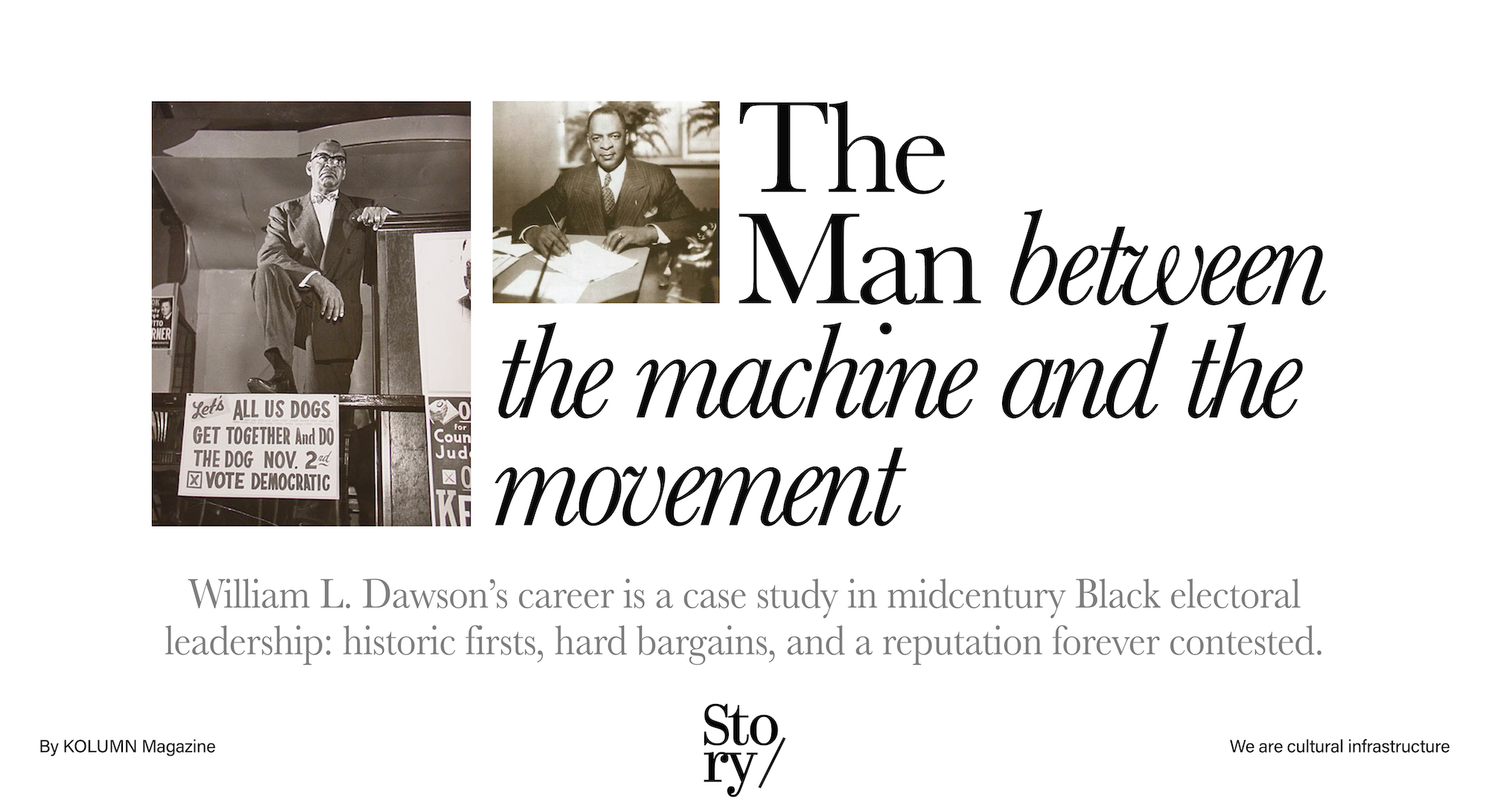

Dawson’s life sits at the most charged intersection of twentieth-century Black politics: between the machine and the movement, between representation and liberation, between “politics” as the distribution of municipal goods and “politics” as the dismantling of an American caste system. He made history repeatedly—most notably in 1949, when he became the first African American to chair a standing committee in the U.S. House of Representatives. Yet his reputation has never been settled into uncomplicated reverence. Admirers point to the services he delivered, the doors he opened, the votes he protected, and the institutional firsts that changed what seemed possible for Black lawmakers. Critics point to what he did not do—what he declined to risk, what he postponed, what he softened—especially as a bolder, mass-based civil-rights insurgency reshaped the meaning of leadership.

To write about William L. Dawson as an “activist” is to expand the category beyond street marches and courtroom drama. Dawson’s activism was managerial, bureaucratic, and deeply local. It was the activism of building a durable organization and using it, year after year, to extract resources from a political system that rarely gave them away. In his prime, he ran what many historians and Chicago chroniclers describe as the city’s first major Black political machine: a disciplined network that delivered votes and demanded patronage in return. His method was an argument: that Black communities, facing exclusion from labor markets, housing, and public services, could not afford to treat politics as symbolic performance. Politics had to be productive.

That argument shaped his ascent—and later, the dispute over his legacy.

From Albany to Chicago: An education in constraint

Dawson was born William Levi Dawson on April 26, 1886, in Albany, Georgia, in a world where the promises of Reconstruction had been replaced by a rigid, violent architecture of segregation. The formal record, preserved in congressional biography, reads like a compressed itinerary of ambition: public schools, higher education, law school, military service, and then a career that threads through city council chambers and the marble corridors of the Capitol. But behind those lines is a broader story familiar to many Black Americans of his generation: the pursuit of credentials as both shield and key.

He studied at Fisk University in Nashville—one of the most significant historically Black institutions in the country—at a time when higher education for Black students was still treated by many white institutions as either a threat or a charity. Fisk’s culture of intellectual seriousness, racial uplift, and disciplined aspiration was a crucible for a generation of Black professionals who would go on to argue—sometimes in harmony, sometimes in conflict—about how a marginalized people should negotiate American democracy.

He eventually made his way to the Chicago area to study law at Northwestern University.) For Dawson, Chicago was not just a destination; it was a laboratory. The Great Migration was reshaping the city’s South Side, expanding Black neighborhoods and political potential, while simultaneously hardening lines of segregation in housing and employment. The ward system, so often caricatured as corrupt, offered something that Jim Crow Georgia did not: the possibility that Black votes could be aggregated, disciplined, and made indispensable.

World War I briefly pulled Dawson into a different hierarchy. He served overseas as a first lieutenant in a segregated U.S. Army unit. The experience of serving a nation that enforced racial separation in uniform was, for many Black soldiers, both radicalizing and clarifying. It underscored that American citizenship could demand sacrifice without guaranteeing dignity. Dawson returned to Chicago, gained admission to the bar, and built a legal practice.

In the early part of his career, he moved through the Republican Party—a route that still made sense for many Black voters and politicians in the first half of the twentieth century, given the GOP’s historical connection to emancipation and Reconstruction. But Chicago was changing, and so were the incentives. By the 1930s, the city’s Democratic machine was consolidating control, and Dawson proved adept at understanding what many moralists resist admitting: political parties are often less ideological homes than vehicles. In Chicago, the vehicle that moved was increasingly Democratic.

The alderman and the organizer: Building a base

Dawson’s rise in Chicago politics began in earnest with local office. He served as an alderman for the city’s Second Ward during the 1930s, a period when Chicago’s political machinery was both expanding and professionalizing its methods of control. The ward committeeman system—neighborhood-level gatekeepers for jobs, favors, and access—was the machine’s nervous system. Dawson became a master of this terrain.

What distinguished Dawson was not simply his ambition but his organizational imagination. Chicago’s Black population was growing, but growth alone did not guarantee leverage. Leverage had to be constructed—through registration, turnout, disciplined precinct operations, and the credible threat that votes could be delivered or denied. Over time, Dawson assembled a political operation that worked within the larger Cook County Democratic Organization while also functioning as its own, Black-centered submachine.

This “submachine” arrangement has often been described in blunt terms: Dawson helped deliver Black votes to the broader Democratic apparatus, and the apparatus returned patronage and services that Dawson could distribute, reinforcing loyalty and organization. It was the logic of survival under constrained options: if the city’s spoils system was the way public resources flowed, then Black communities needed brokers who could tap that stream, not merely denounce it from the bank.

But brokerage is inherently controversial. It creates dependency and resents competition. It can elevate a leader while narrowing the pathways for rivals. Dawson’s machine—like all machines—could reward friends and punish defectors. That capacity was part of his power and part of the suspicion surrounding it.

Congress and solitude: The only Black member

In 1942, Dawson was elected to Congress from Illinois’s First District, beginning a tenure that would last until his death in 1970. At the time he entered the House, he was, once again, the only African American member of Congress—an isolation that carried both symbolic weight and practical constraints. To be the lone representative of an entire race’s political aspirations is to be positioned as a spokesperson even when you have not claimed the role, and to be judged for every choice as if it were a national referendum on strategy.

Dawson’s congressional biography highlights the conventional milestones: long service, committee roles, chairmanships, and the steady accumulation of institutional seniority. Yet the deeper question is what he did with that seniority at a moment when the civil-rights agenda was intensifying and the Democratic Party’s internal contradictions were approaching crisis. Dawson was working inside a Congress where segregationists held enormous power through seniority and committee control, and where “progress” often depended on bargains so incremental they could feel like evasions.

Even so, Dawson engaged in civil-rights-related fights that were less theatrical but consequential. Accounts of his career note his opposition to the poll tax and his involvement in political participation efforts. He was also credited with helping defeat an effort that would have undermined the Truman administration’s move toward integrating the armed forces—the Winstead Amendment, proposed as a way to allow service members to opt out of integrated units. That kind of legislative maneuvering—the quiet counting of votes, the cultivation of allies, the prevention of rollback—rarely makes for heroic iconography. But it shapes lives.

Dawson’s significance is partly anchored in institutional history: he became, in 1949, the first African American to chair a standing committee in the House, leading the Committee on Expenditures in the Executive Departments (and later its successor structures). In the midcentury Congress, committee chairmanship was not ceremonial. Chairs controlled agendas, investigations, staffing, and influence. To place a Black man in that role was to signal a shift in what the institution could accommodate—though not necessarily in what it would prioritize.

A federal account compiling the history of Black Americans in Congress notes contemporary press recognition of Dawson’s rise, including a New York Times item in January 1949 acknowledging his committee leadership. The point isn’t the applause itself; it’s the fact of visibility. His chairmanship represented a breach in an implicit color line within legislative power.

The critique: Moderation, compromise, and the NAACP’s impatience

The problem with being a historic “first” is that you become a symbol for people with competing demands. Dawson’s critics—particularly civil-rights advocates who wanted sharper confrontation—argued that he did not fully deploy his authority in service of transformative change. The U.S. House’s own historical materials do not avoid this tension. They note that Dawson was criticized for not fully using his leadership roles to push meaningful change for African Americans, and that the NAACP condemned what it described as his “silence, compromise and meaningless moderation” on key issues, including his refusal to back measures aimed at defunding segregated schools.

Those words—silence, compromise, meaningless moderation—strike at the core of the debate over Dawson. To his supporters, compromise was not meaningless; it was the currency of governance, and it bought tangible benefits. To his critics, compromise was the mechanism by which segregationists survived: they traded small concessions for time, and time for the maintenance of power.

Dawson’s defenders could point to an environment where overt civil-rights advocacy could collapse coalitions needed for any legislative progress. The Southern bloc within the Democratic Party was a veto power. To maintain committee authority, Dawson needed working relationships with men who might privately despise him or publicly oppose everything he represented. That is the cruel paradox of midcentury congressional advancement for Black lawmakers: to climb, you often had to reassure people who were invested in your limited reach.

Dawson’s critics could point to another fact: there are moments when moderation is not prudence but permission. When civil rights activists were putting their bodies on the line in the South, and when Black Chicagoans were confronting segregation in housing and policing at home, “inside” strategies could look like excuses—especially if they seemed aligned with machine stability more than movement urgency.

Both readings contain truth, which is why Dawson remains such a useful figure for understanding the era. His career forces an uncomfortable question: how do you measure Black political success in a system designed to restrict it? By laws passed? By services delivered? By barriers broken? Or by the distance between what was possible and what was attempted?

Chicago’s Black machine: Patronage as policy

To understand Dawson’s activism, you have to understand the political economy of segregation-era cities. Jobs in municipal departments, federal agencies, and public works projects were not just employment; they were ladders into the middle class, sources of stability, and, for families excluded from private-sector opportunity, a kind of reparative access. Patronage—the distribution of those jobs—was therefore not merely corruption in Black communities. It was, in a limited and compromised way, policy.

Chicago’s PBS affiliate WTTW describes Dawson as the builder of Chicago’s first Black political machine and emphasizes that he used his influence to improve life for African Americans in his district. The National Park Service, in a biographical profile associated with Mary McLeod Bethune Council House, similarly frames his career as one of service and civil-rights advocacy across decades. These accounts underscore the reality that Dawson’s local power mattered. In an era when discriminatory hiring and exclusionary unions could lock Black workers out of opportunity, the ability to secure positions in postal work, transit, public administration, and other government roles could reshape a neighborhood’s prospects.

But Dawson’s model required discipline. Machines are allergic to freelancing. They thrive on predictable turnout and punish insurgency. The machine’s logic also shaped Dawson’s posture toward reform movements that threatened to disrupt the city’s political equilibrium. His critics argued that he prioritized the maintenance of his organization and alliance with the larger Democratic apparatus over confrontations that might weaken his leverage.

Here the Washington Post’s archival reporting on Chicago politics captures part of the historical movement: the way Black political allegiance shifted and consolidated within Democratic power structures, with Dawson as a central figure in that alignment. The story of Black Chicago’s partisan transformation is not reducible to Dawson alone, but he was undeniably one of its most consequential engineers.

In that sense, Dawson’s significance is inseparable from the Great Migration’s political aftermath. Migration created demographic weight. Dawson helped translate that weight into an organizational instrument—an instrument capable of negotiating with City Hall and the national party.

The national party and the choreography of civil rights

Dawson’s influence extended beyond Chicago through his relationship with the Democratic Party’s national structures. In the midcentury period, Black voters were increasingly becoming a cornerstone of Democratic electoral coalitions in Northern cities. Dawson understood that this shift could be expanded—but he also believed it had to be managed carefully to avoid triggering backlash from Southern Democrats who still formed the party’s segregationist spine.

That balancing act helps explain why Dawson often appears, in the historical record, as both a civil-rights participant and a civil-rights disappointment. He supported certain measures and resisted retrenchment, but he also navigated the party’s internal constraints with a cautiousness that could look, from the outside, like timidity.

The U.S. House historical essay on civil rights in Congress uses Dawson as one example of the era’s limits, noting the NAACP’s harsh critique and placing his choices within a broader landscape of institutional barriers and political calculations. It’s a useful frame because it resists caricature. Dawson was not simply a villain of moderation, nor a saint of pragmatism. He was a leader whose approach assumed that survival within an institution could itself be a form of progress—and that survival required compromises that would anger people who wanted rupture, not adaptation.

The tension is also personal. Dawson’s generation carried memories of earlier failures: of Reconstruction’s collapse, of lynching’s impunity, of federal retreat. Many of them concluded that protest without power was a form of vulnerability. The movement generation, especially after World War II, increasingly argued the inverse: that power without moral confrontation was complicity, and that the country’s conscience had to be forced, not courted.

Dawson stood in the crosswinds of that generational shift.

The movement comes north: Chicago, King, and a contested legacy

Dawson’s most controversial decisions, for many modern readers, are tied to the 1960s, when civil-rights activism turned toward Northern segregation—housing discrimination, school inequality, and police practices that were not codified as Jim Crow but were no less real.

In Chicago, the arrival of Martin Luther King Jr.’s campaign for fair housing and desegregation confronted the city’s political class with a moral reckoning that could not be resolved by patronage alone. Dawson, deeply embedded in the machine ecosystem, did not become a visible champion of King’s efforts. Accounts of his career note that he did not support King’s Chicago campaign, and that he sometimes undercut integration efforts that threatened the machine’s electoral calculations.

If you are inclined to condemn Dawson, this is the evidence you cite: a Black leader, powerful within the system, declining to align with a movement that sought to change that system’s architecture. If you are inclined to defend him, you might argue that Chicago’s racial politics were combustible and that machine leaders believed, however cynically, that they were preventing backlash and preserving the incremental flow of resources.

Either way, the record makes one thing clear: Dawson’s strategy was built for a world where Black advancement came through negotiation inside institutions. The 1960s increasingly demanded something else—mass disruption, moral theater, the deliberate destabilizing of unjust arrangements. Dawson’s instincts were not built for that, and he became, for many, an emblem of what the movement believed it had to supersede.

How to measure Dawson

The temptation in retrospective storytelling is to sort figures into heroes and obstacles. Dawson resists that sorting, and the resistance is the point. His life reveals the complicated truth that Black political progress in America has often required both types of leadership: the insurgent who forces the question and the broker who translates urgency into policy and access.

Dawson’s achievements are measurable. He served in Congress from 1943 until 1970. He chaired powerful committees, becoming the first Black chair of a standing House committee. He operated as a gatekeeper and mentor within Chicago politics, helping shape a generation of Black officeholders and making Black votes central to the city’s Democratic arithmetic.

His limitations are also measurable, though more interpretive. He was criticized—by major civil-rights organizations—for insufficient boldness. His machine politics could narrow democratic participation inside the Black community by enforcing loyalty and punishing dissent.) He maintained alliances that, at times, required downplaying civil-rights language in national politics.

The most honest way to hold these truths together is to see Dawson as a product of his environment and an architect of a new one. The Jim Crow South taught him that rights on paper could be ignored without enforcement. Chicago taught him that enforcement often required leverage. Congress taught him that leverage could be limited by coalition math. The movement taught the country that coalition math could be morally insufficient.

In that sequence, Dawson is not a footnote. He is a chapter: a case study in how Black political leadership evolved in the decades between the first Great Migration wave and the legislative victories of the 1960s. He represents a generation that believed their task was to get inside the room and stay there. His successors, inspired by the movement’s momentum, increasingly believed the task was to rebuild the room itself.

Dawson died in office in Chicago on November 9, 1970, closing a career that spanned the era from post-Reconstruction backlash to the dawn of modern Black electoral expansion. His legacy remains unsettled because the questions he embodied remain unsettled, too: Is the purpose of politics to deliver relief within the existing system, or to transform the system that makes relief necessary? When does pragmatism become surrender—and when does idealism become neglect?

William L. Dawson’s life does not answer those questions neatly. What it offers instead is a lens: the hard arithmetic of power, written in precinct lists and committee gavels, and in the enduring argument over what Black leadership owes to its people when the nation’s promises arrive slowly—or not at all.

More great stories

The Kissing Case: How a Child’s Game Became a Jim Crow Trial of Power