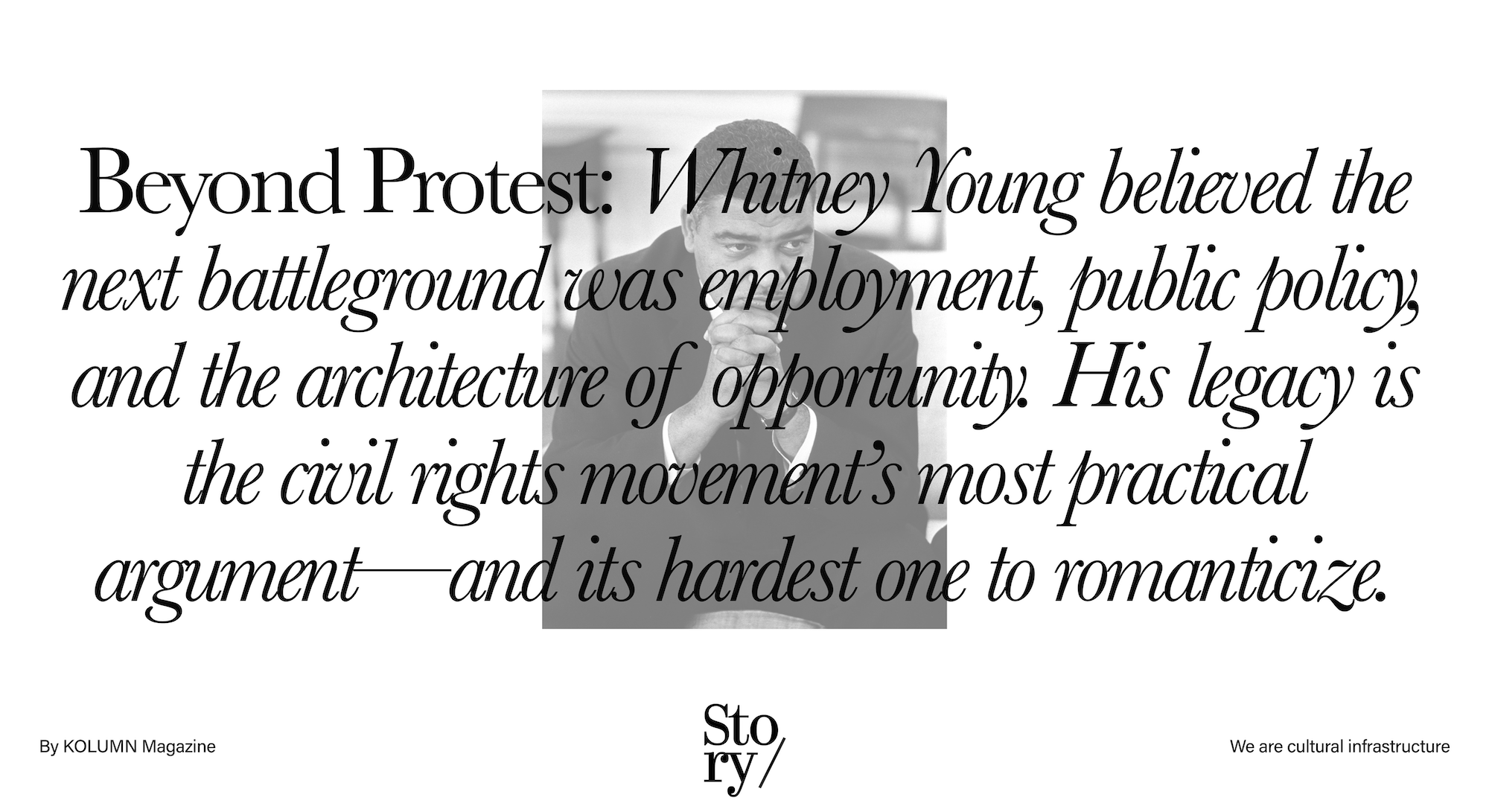

Young built the movement by entering the establishment and trying to reorganize it from the inside.

Young built the movement by entering the establishment and trying to reorganize it from the inside.

By KOLUMN Magazine

A certain kind of American story loves a straight line. A child encounters injustice. A movement erupts. A hero rises. The arc bends. The credits roll. It is a story built for posters and anniversaries—clean enough to teach, tidy enough to commemorate.

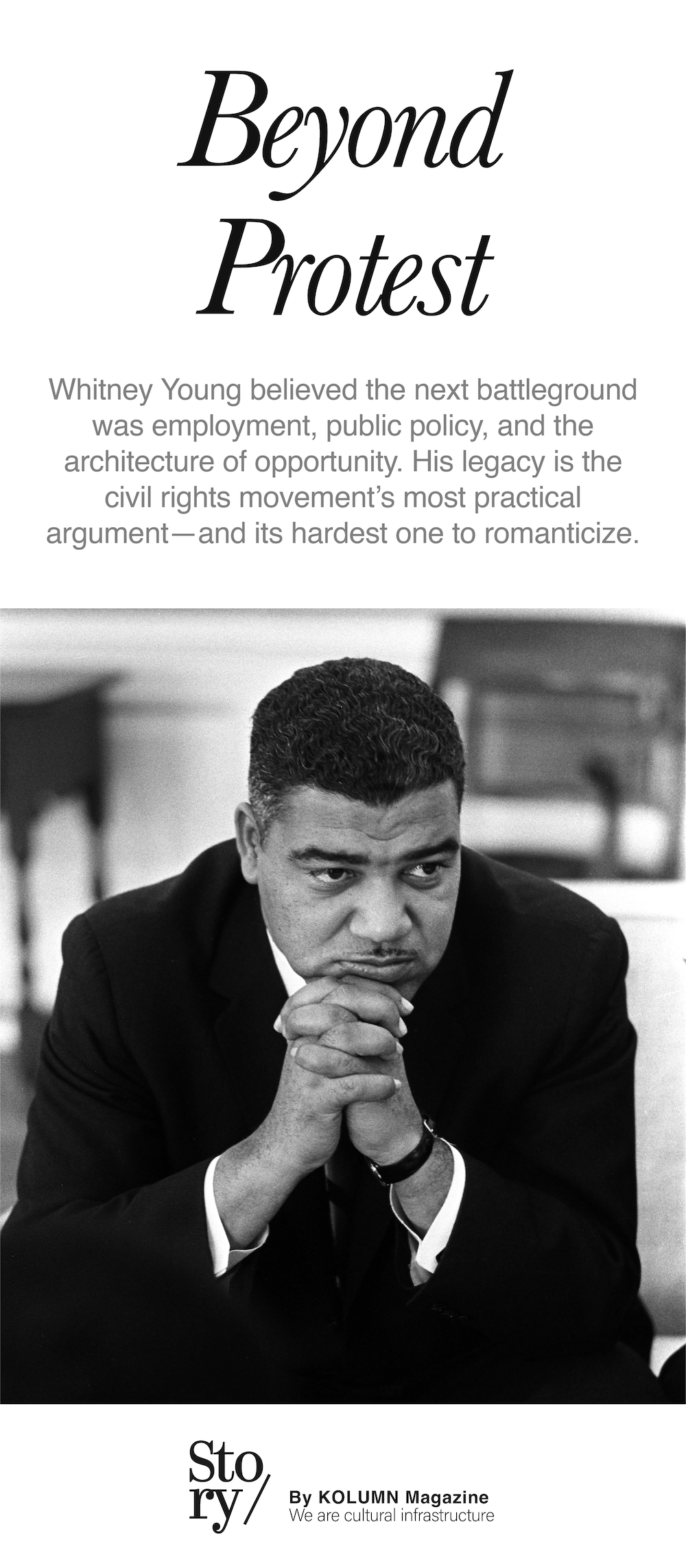

Whitney Moore Young Jr. never fit the poster.

He was not the movement’s purest symbol, nor its most lyrical orator. He did not build his power by rejecting the establishment; he built it by entering the establishment and trying to reorganize it from the inside. Where others aimed to redeem the nation by forcing it to see its sins, Young aimed to redeem it by forcing it to change its systems—employment pipelines, housing markets, government budgets, corporate cultures, the bureaucratic machinery that decides who gets to live in the sunlight and who remains trapped in the shade.

Young’s wager was that civil rights could not survive on conscience alone. It needed implementation. It needed administrators and planners. It needed, in his phrase, “social engineers”—people who could translate moral demand into policy and opportunity. That conviction made him essential in the 1960s, when the country’s legal architecture was being rebuilt at speed and scale. It also made him controversial, sometimes mistrusted, and occasionally caricatured: too friendly with white corporate power, too close to presidents, too willing to compromise, too cautious for a generation whose patience had been burned away by police dogs and voter intimidation and the exhaustion of waiting.

And yet, when you trace the American civil rights story beyond the landmark legislation—into the struggle over jobs, housing, training, urban investment, and the everyday mechanics of dignity—Young is everywhere. He reshaped the National Urban League into a muscular institution with national reach, pushing it from cautious respectability into bolder advocacy while keeping it funded and politically connected. He pressed corporate America to hire Black workers for positions it had long reserved for whites, and he did it by learning the language of corporate risk and reputation, by sitting across from CEOs and insisting that integration was not charity but national self-preservation. He advised presidents and pressured them, praising them when praise could purchase progress and confronting them when rhetoric turned thin.

He also died suddenly, far from home, in Lagos, Nigeria, in 1971—only 49 years old—at the very moment when the movement he had helped advance was splintering into arguments about what “freedom” would actually require. The man who had built a career on turning public ideals into institutional practice left behind a legacy that can feel less cinematic than others, but arguably more instructive: civil rights as an operational problem, a question of whether America is willing to pay for the society it claims to be.

To understand Whitney Young is to understand the movement’s inside game—its negotiations, its budgets, its uneasy alliances, and its constant wrestling match with the limits of “progress” when progress threatens power.

Lincoln Ridge, the making of a social worker, and the discipline of expectation

Whitney Young was born on July 31, 1921, in Kentucky, in a world where segregation was not simply a set of laws but a total environment—one that trained Black families to read danger in small gestures and to find excellence under constraint. His father, Whitney M. Young Sr., was an educator who led the Lincoln Institute, a Black preparatory school that functioned as both refuge and proving ground. His mother, as multiple biographical accounts note, taught as well; the home was steeped in the idea that survival required discipline and that discipline, if sharpened, could become leadership.

Young’s early life is often described through accomplishment—college at a young age, a quick ascent through educational and professional spaces that were not designed to welcome him. But what matters as much as the resume is the sensibility it produced. Young developed a belief that credentials were not assimilation; they were leverage. In a segregated society, excellence could be a shield. In a changing society, it could be a tool for prying open doors.

He attended Kentucky State College (now Kentucky State University), graduating young, and began working as a teacher and coach—work that placed him in the intimate space where aspiration meets limitation, where young people absorb the story society tells them about what they are allowed to become. During World War II, he served in the U.S. Army, and his wartime experience became one of the formative contradictions of his life: the United States asking Black citizens to fight for democracy abroad while denying them full citizenship at home.

One account from the National Association of Social Workers Foundation notes that during his time in the Army he studied engineering at MIT, adding another layer to the portrait: Young as a man trained not only in moral argument but in technical thinking, systems, and structure. He would later bring that “systems” instinct into civil rights work in a way that distinguished him from leaders whose strength was primarily prophetic. Young could be prophetic, too—but he was also managerial. He wanted to know how things worked, who controlled them, and where the levers were.

After the war he earned a master’s degree in social work at the University of Minnesota. Social work, at its best, is the profession of consequences. It places you among the people harmed by policy and economics, and it forces you to measure ideals against lived reality: the rent due, the job denied, the school underfunded, the hospital too far away. It is not abstract. It is embodied.

Young never stopped being a social worker, even when he became a national figure. That background shaped his politics. He was less interested in symbolism than in outcomes. If a policy sounded righteous but did not produce jobs, training, housing, or access, he treated it as insufficient.

The Urban League before Whitney Young—and what he decided it had to become

The National Urban League, founded in the early twentieth century, had long played a particular role in Black life: assisting Black migrants, connecting them to employment opportunities, advocating against discrimination while maintaining an image palatable to white institutions that controlled money and policy. It was an organization built for survival in a hostile society, and that often meant carefulness—incrementalism, negotiation, diplomacy.

By the time Young rose to lead it, the movement’s public face was shifting fast. Sit-ins and boycotts were rewriting the rules of visibility. The moral drama of segregation was playing on television screens, and direct action was forcing the country to confront what it had tolerated. Young did not dismiss that energy; he understood it as a catalyst. But he also believed something else: that direct action alone could not build the society that would need to exist after the laws changed.

In 1961, Young became executive director of the National Urban League, stepping into a position that would place him at the center of the decade’s argument about strategy. Accounts of his tenure emphasize the transformation in scale—how he expanded staff, budget, and institutional reach, turning the League into a national operation capable of pressing employers and policymakers across the country. The Smithsonian’s National Museum of African American History and Culture describes his election as a turning point that built on years of earlier work and positioned him to steer the organization into a more visible, more forceful era.

Young’s skill was that he could speak to multiple Americas at once. To Black communities, he spoke about dignity and access, about the insult of a segregated labor market and the theft of opportunity. To white corporate leaders, he spoke about wasted talent, social instability, and the reputational cost of staying on the wrong side of history. To presidents, he spoke in the language of national crisis and national investment: if the country refused to deal with unemployment, housing segregation, and urban poverty, it would face disorder that could not be policed away.

He was, in other words, a translator—of moral urgency into institutional language.

That translation came with risk. Translators are sometimes accused of softening what they translate. But Young believed the translation itself was power: if you could force the establishment to hear the demand in terms it could not ignore, you could force it to respond.

“Social engineers”: The philosophy behind Young’s inside game

A revealing window into Young’s thinking sits in a 1964 interview conducted as part of Robert Penn Warren’s oral history project, “Who Speaks for the Negro?” preserved through Vanderbilt. There, Young describes the Urban League’s role in terms that are both blunt and strategic—casting the organization as planners and implementers working at the level of policy and the “highest echelons” of corporate and governmental life.

That framing tells you nearly everything about Young’s approach. He did not romanticize marginality. He wanted access to power because he wanted to alter what power produced. He saw policy as the movement’s second front, and he believed that if civil rights leaders abandoned that front, it would be captured by people who had no interest in justice.

This was not a purely technocratic worldview. Young was not blind to the spiritual and psychological dimensions of racism. But he was convinced that racism endured not only because of hatred but because of structure—because discrimination was profitable, because segregation protected property values, because networks reproduced themselves, because institutions were designed to keep certain people out.

To confront that, you needed more than protest. You needed what Young kept pushing toward: training programs, hiring commitments, federal investment, housing enforcement, and a credible threat that America’s moral standing and domestic stability were on the line.

This is one reason he placed employment at the center of civil rights. A job is not simply income. It is status, security, and leverage. It is the difference between participating in democracy and merely living under it.

The March on Washington and the movement’s coalition politics

Young’s role in the historic 1963 March on Washington is often mentioned as evidence of how he helped align institutional civil rights work with the movement’s mass energy. Biographical accounts note that the Urban League, under his leadership, became a co-sponsor of the march—a decision that mattered because it signaled that the inside game and the street game were not enemies, at least not yet.

That sponsorship also reflects Young’s belief in coalition. He understood that civil rights victories required multiple kinds of pressure operating simultaneously. The march created moral spectacle; the Urban League could help translate that spectacle into demands that employers and government agencies could not evade.

But coalition politics comes with friction. Young’s willingness to work closely with white allies—particularly powerful business leaders—became one of his defining controversies. To some activists, corporate partnerships looked like capture. To Young, they looked like leverage. The people who controlled jobs, he argued, needed to be forced—through persuasion, pressure, and public expectation—to open those jobs.

If you were trying to move the labor market, you had to deal with the people who ran it.

That pragmatic stance is easier to criticize than to replace. The civil rights movement, like any movement, had to decide whether its goal was moral purity or material change. Young leaned toward change, even when it required sitting in rooms that made others furious.

Advising presidents—and refusing to be decorative

In the 1960s, the federal government was both target and instrument. It upheld segregation through local complicity and national indifference, and it also possessed the power to disrupt segregation through legislation, enforcement, and investment. Young understood that paradox and chose to engage it directly.

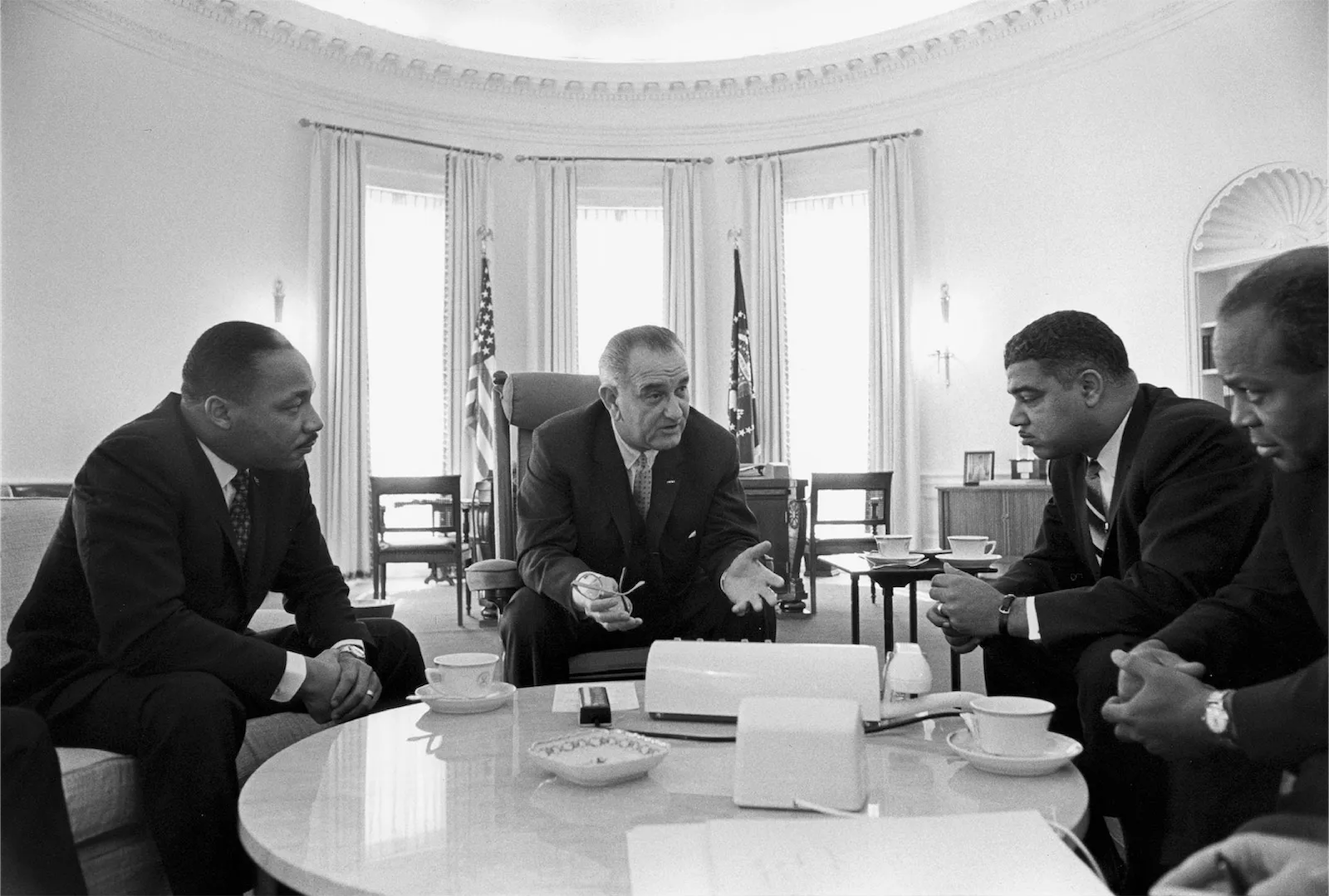

He became known for close access to presidents, particularly Lyndon B. Johnson. The relationship was not merely social. Johnson’s Great Society and War on Poverty agenda sought to address structural inequality in ways that could align with Young’s emphasis on jobs and opportunity. The American Presidency Project preserves remarks from Johnson at a National Urban League gathering in 1964—language that frames racial injustice as an “unfinished work,” and that publicly honors Young as a longtime friend.

Presidential friendship can be a trap; it can turn civil rights leaders into moral decorations, summoned for photo ops and ignored in policymaking. Young fought not to be decorative. He pressed for what he called a domestic “Marshall Plan”—a large-scale reinvestment in cities, housing, education, and training, premised on the idea that America had spent lavishly to rebuild Europe after World War II and could spend similarly to rebuild the lives it had marginalized at home.

Accounts differ in the details and the exact numbers attached to the plan, but multiple historical references describe it as a massive, long-term investment proposal aimed at dismantling the “ghetto” conditions produced by policy and neglect. The point was not simply funding; it was scale. Young argued that piecemeal programs would not be enough to undo decades of structural damage. A serious nation would spend serious money.

That insistence helps explain why Young’s legacy feels newly relevant in an era when people debate whether inequality is a matter of personal responsibility or public design. Young was clear: America had designed inequality into its cities and labor markets. Undoing it would require redesign, not lectures.

In 1968, Young received the Presidential Medal of Freedom, a recognition that underscored his national stature even as the decade’s optimism was collapsing into assassinations, uprisings, and political backlash.

“To Be Equal”: Argument as strategy, and equality as a systems problem

Young was not only an administrator and leader; he was a writer and public intellectual who tried to give the movement a vocabulary for economic justice. The National Urban League’s long-running “To Be Equal” column explicitly traces its inspiration to Young’s 1964 book of the same name, placing him at the foundation of a tradition of policy-focused argument within the organization.

The title itself—To Be Equal—captures Young’s temperament. It is not romantic. It is not metaphorical. It is direct, almost contractual. It implies that equality is a condition to be achieved and verified, not a sentiment to be performed.

Young’s later book, Beyond Racism: Building an Open Society (published in 1969), further signals his insistence that the country had to confront not only prejudice but the structures that prejudice shaped and protected. Even the framing—“building”—reveals his orientation. Civil rights, for Young, was a construction project. It required public policy and private sector change, and it required individuals to understand themselves as participants in a society that could be redesigned.

That focus on “building” also places him in a category of civil rights leadership that sometimes gets less cultural attention than the movement’s moral drama: the builders, the administrators, the people who treated civil rights as an ongoing governance problem.

The criticism: “Sellout” politics, corporate closeness, and the movement’s shifting mood

Any honest account of Whitney Young must confront the critique that followed him: that he was too close to white power, too invested in corporate partnerships, too willing to accommodate. Those critiques did not come only from extremists or from outside the movement; they emerged from within Black political life as the 1960s progressed.

The rise of Black Power rhetoric, the frustrations of slow economic change, and the rage born from police violence made “integration” sound to some like surrender. Young’s insistence on working with CEOs, negotiating with presidents, and operating within institutional channels could be interpreted as a refusal to confront the system’s brutality.

But Young did confront it—just differently. He confronted it by insisting that discriminatory hiring practices were not just immoral but incompatible with the country’s professed values and stability. He confronted it by demanding federal investment at a scale that frightened moderates. He confronted it by pushing professional fields—like architecture—to acknowledge their complicity in urban renewal projects that damaged Black communities, a critique preserved in accounts of his 1968 address to the American Institute of Architects and the profession’s subsequent responses.

If anything, Young’s controversy exposes a deeper question that still haunts American politics: Is power best challenged from outside or reshaped from within? Young’s life suggests the true answer is that both pressures are necessary—and that the inside strategy, though less glamorous, is often where durable change is operationalized.

Urban renewal, housing, and the argument that the built environment is civil rights

Young’s significance expands when you stop treating civil rights as only voting rights and public accommodations and begin seeing it as the right to live in safe housing, to access opportunity, to avoid neighborhoods engineered for neglect.

In that sense, Young’s attention to housing and urban policy reads like foresight. Discussions of his influence often connect him to fair housing advocacy and broader fights over segregation in the built environment. He pushed professionals and policymakers to recognize that the physical design of American cities—where highways were placed, which neighborhoods were razed for “renewal,” where investment flowed—was not neutral. It was politics in concrete.

That is why his 1968 address to architects remains notable. The American Institute of Architects’ own retrospective on the speech describes Young challenging the profession’s lack of diversity and its relationship to urban “renewal” projects that were tearing apart American cities. Whatever one thinks of professional associations, the point is larger: Young insisted that civil rights was not a narrow legal category. It was the design of opportunity itself.

The last act: Lagos, a sudden death, and the strange quiet that followed

On March 11, 1971, Whitney Young died in Lagos, Nigeria, while attending a conference. Multiple accounts describe his death as a drowning while swimming, though early reporting included conflicting explanations, including a reported brain hemorrhage. The facts of the moment remain less culturally fixed than the facts of other civil rights martyrs, perhaps because the death lacked the visible cruelty of assassination, perhaps because it happened far from American streets and cameras.

But the aftermath signaled how prominent Young was in national life. President Richard Nixon delivered a eulogy at Young’s funeral, a marker of Young’s status as one of the rare civil rights leaders who could command respect across political divides—even as those divides were hardening into the backlash politics that would define the coming decades.

His death also created an institutional gap. The Urban League would continue, led by successors who carried forward parts of his vision, but the particular combination Young embodied—social worker and policy strategist, insider and critic, coalition builder and structural agitator—was difficult to replace.

And the country he left behind was changing mood. The optimistic idea that the federal government could be a reliable engine of justice was fading amid Vietnam, inflation, and political realignment. Corporate America was learning how to adopt the language of inclusion without necessarily altering power. Urban crisis was becoming a code word used to justify austerity and policing rather than investment.

In that sense, Young died at the hinge of eras: after landmark civil rights laws but before the country decided how much it actually believed in the society those laws implied.

What Whitney Young’s life argues—right now

Whitney Young’s lasting significance is not simply that he was a major civil rights leader; it is that he defined civil rights as an economic and institutional mandate. He treated employment discrimination as a moral emergency. He treated housing and urban policy as civil rights terrain. He treated budgets as ethical documents. He treated the private sector as accountable to public values.

In the modern era, when diversity initiatives can be packaged as branding and when public policy can be reduced to slogans, Young’s approach feels both bracing and demanding. He did not confuse representation with justice. He pushed for access to the actual machinery of opportunity: hiring, training, promotion, professional pipelines, federal spending, enforcement.

He also offers a caution to contemporary activists and institutions alike. If you build a movement only around moral performance, you may win attention without winning systems. If you build a movement only around access to power, you may win meetings without winning change. Young tried—often imperfectly, sometimes controversially—to do both: to use access to shift systems, and to use moral urgency to make access productive.

That tension is not a flaw in his story. It is the story.

For a publication like KOLUMN—committed to long-form reporting that treats history as living infrastructure—Young’s life is a reminder that liberation is not only declared; it is administered. It requires both the people who force the country to see and the people who force the country to implement what it claims to believe.

Young spent his life insisting that the nation’s ideals were measurable. The question he leaves behind is simple, and still unanswered: Is America willing to do the expensive, unglamorous work of being what it says it is?

More great stories

The Kissing Case: How a Child’s Game Became a Jim Crow Trial of Power