Parks didn’t just enter rooms where Black artists were excluded. He rearranged the furniture.

Parks didn’t just enter rooms where Black artists were excluded. He rearranged the furniture.

By KOLUMN Magazine

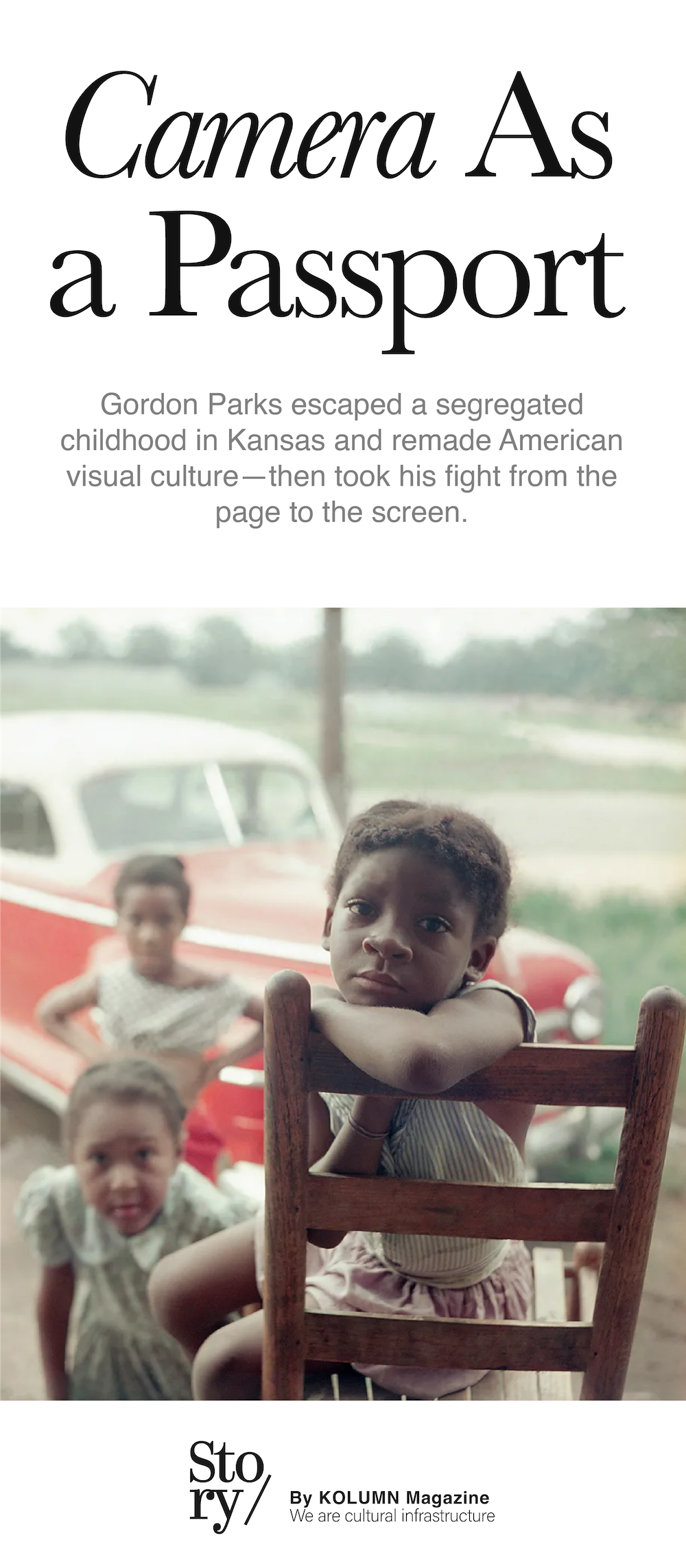

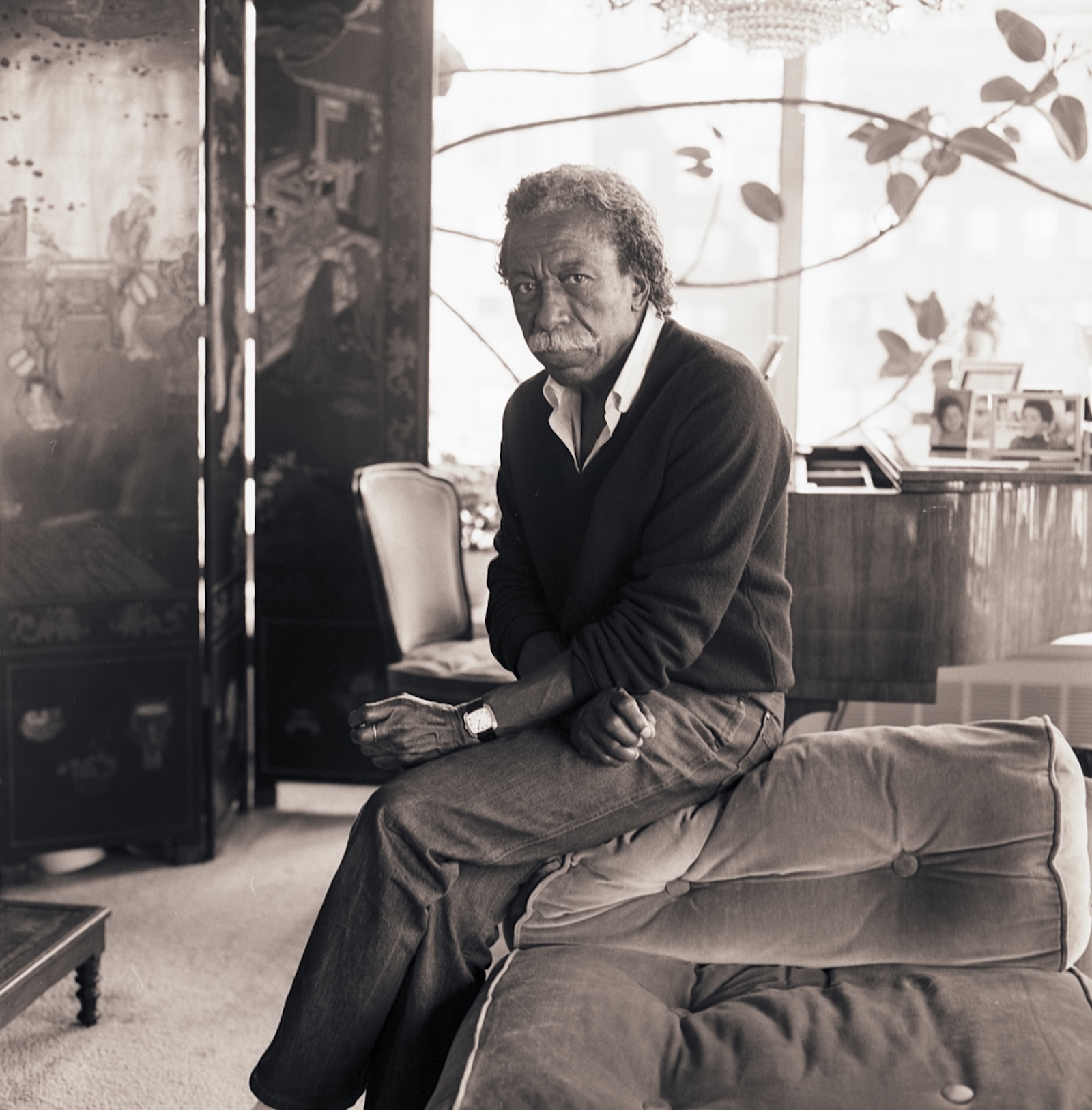

The best-known Gordon Parks images feel like they arrived already etched into public memory—so complete, so formally sure of themselves, that it can be easy to forget how much resistance they contain. The photographs are not simply records of what happened. They are arguments about what deserves to be seen, what counts as evidence, and who gets to author the story of American life.

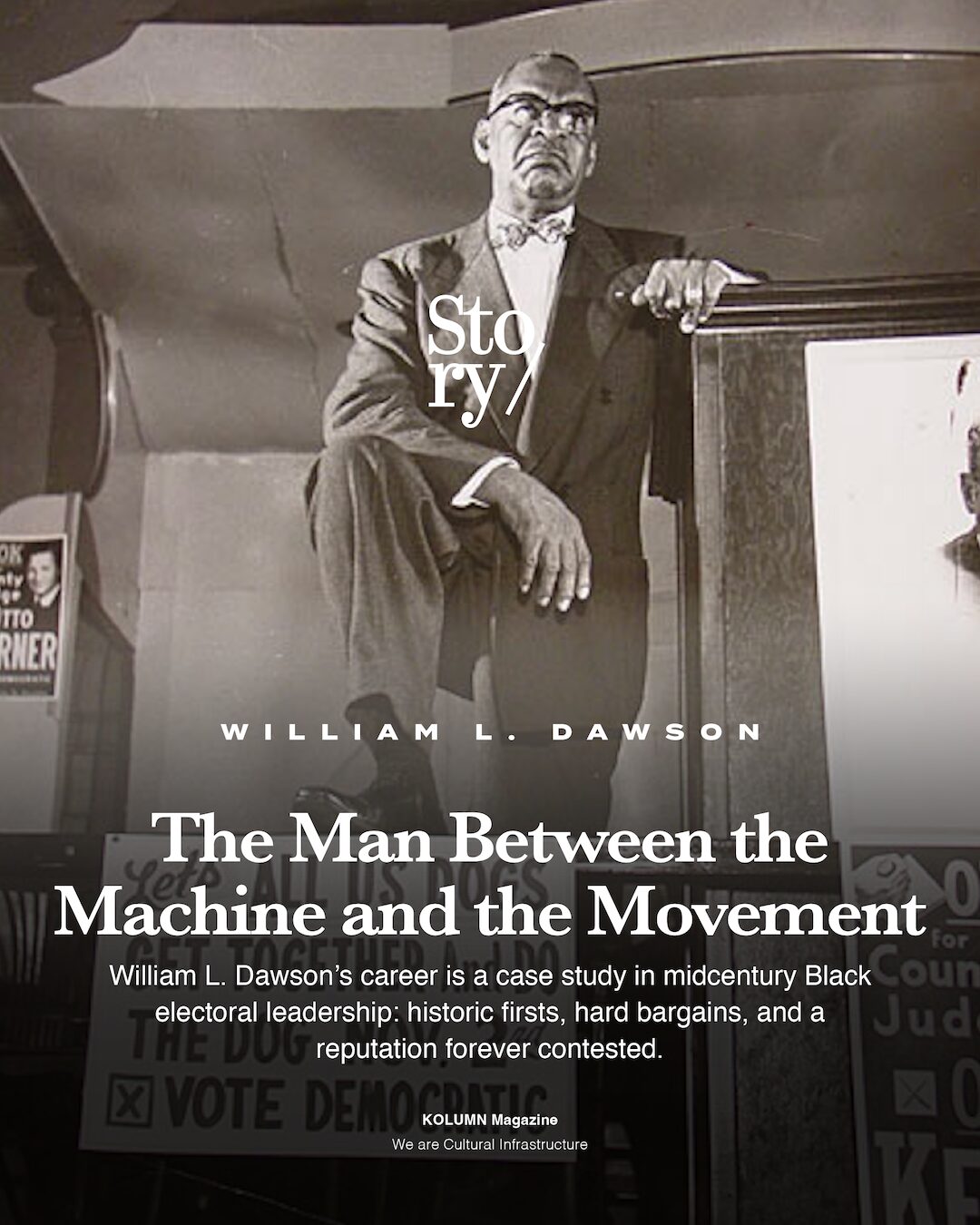

Start with the image most often used as a shorthand for his moral clarity: American Gothic, the 1942 portrait of Ella Watson, a Black government cleaning woman in Washington, D.C., posed with mop and broom before an American flag. The photograph is famous in part because it’s so legible: a nation’s promise held up against its daily humiliations. But its legibility is also its provocation. Parks was working within a federal documentary apparatus—on assignment within the Farm Security Administration’s photographic project—yet he created an image that reads as indictment, not civic PR. The picture takes a beloved icon of American art and turns it into a question about who the republic was built for, and at whose expense. The Gordon Parks Foundation describes the portrait as among the most celebrated and influential photographs of the twentieth century, and the Foundation’s continuing work around the picture has emphasized the depth of Watson’s life and the ethical stakes of how she is remembered.

That combination—formal mastery with moral pressure—became Parks’ signature across media. He carried it into fashion photography and celebrity portraiture, into long-form photo-essays for Life magazine, and eventually into Hollywood, where he directed films that reconfigured who could occupy the center of American genre cinema. The Washington Post obituary captured the range succinctly: Parks broke color barriers as a photographer, filmmaker, and poet whose chronicles of Black experience made him a cultural icon. The Guardian’s obituary was equally plain about his reach, from Life to Shaft and beyond, noting how his films were quickly pulled into the debates—often reductive debates—about “blaxploitation” even as Parks resisted being boxed by the label.

To write about Gordon Parks seriously is to treat him not as a “first” who merely arrived early, but as a strategist who understood institutions: how they curate empathy, how they sell glamour, how they flatten complexity, and how they can be forced—sometimes—into telling fuller truths. Parks didn’t just enter rooms where Black artists were excluded. He rearranged the furniture. He also left behind a career that is difficult to summarize because it belongs to multiple traditions at once: documentary photography, magazine journalism, portraiture, literature, music composition, and commercial cinema. The National Gallery of Art notes that Parks was, in addition to a photographer for publications including Life, Ebony, and Vogue, also a poet, author, musician, and filmmaker—an inventory that still reads like an argument against narrowness.

He was born in 1912, in Fort Scott, Kansas, the youngest of fifteen children, and he died in 2006 in New York. Between those endpoints sits one of the most consequential American careers of the twentieth century—not just because Parks captured history, but because he pressured history to acknowledge Black life as central, not supplemental.

Kansas: A childhood shaped by exclusion, and a temperament shaped by escape

Fort Scott, Kansas, sits in the national imagination as “middle America,” a phrase that can flatten as much as it describes. For a Black child in the early twentieth century, “middle America” often meant a close-up education in the mechanics of segregation: who is welcome where, which doors are decorative, which rules are written, which are enforced by violence and informal consensus. Parks’ early life—documented in detail by the Gordon Parks Foundation’s biography and chronology—was marked by economic precarity and the restrictions of a segregated environment.

He did not emerge from Kansas with an uncomplicated nostalgia. Parks’ later work repeatedly returned to the question of what a childhood in constraint does to a person: the way it sharpens observation, the way it can teach you to anticipate danger, the way it can also train you to recognize the codes of power—how power dresses, speaks, smiles, and deflects. In Parks’ case, those lessons did not fossilize into bitterness. They became a kind of kinetic ambition: an insistence on movement. Even the romance sometimes attached to his life—Parks as the charismatic polymath in tailored clothes, the artist who could navigate both Harlem and high society—can obscure the more bracing fact that his movement was not simply taste or temperament. It was survival strategy.

Parks has often been described as largely self-taught, an artist who acquired his camera and his eye without an elite pipeline. That self-making is central to his mythology, but it is also central to his politics: he understood what it meant to be underestimated, to be told that creative aspiration was frivolous or impossible for someone of his background. The Gordon Parks Foundation frames him as a humanitarian with a deep commitment to social justice whose work documented race relations, poverty, civil rights, and urban life across decades. That commitment didn’t drop into his life fully formed; it grew out of a world that repeatedly signaled to him that Black suffering was normal, invisible, or deserved. Parks would make a career out of refusing all three.

The camera as an instrument of agency

One of the strongest through-lines of Parks’ career is the idea that the camera is not passive. It can be protection; it can be leverage; it can be a way of entering spaces otherwise closed; it can be a way of reversing the gaze—of making the powerful aware that they are being watched and judged. This is not a metaphor in Parks’ life. It is an operational reality.

He arrived in Washington, D.C., in 1942 with a Rosenwald Fund fellowship and began working in the Farm Security Administration’s photographic unit under Roy Stryker, at a moment when documentary photography was already a battleground for narratives about the Depression, labor, and national identity. Parks’ vantage point was distinct: he experienced the capital not as a civic symbol but as a segregated city, and he understood how bureaucracies could naturalize indignity. His assignment could have produced a series of safe images—poverty as scenery, segregation as background. Instead, Parks made pictures that turned social structure into subject.

American Gothic is the emblem, but not the only example. The LIFE.com presentation of the photograph emphasizes that Parks was stung by racial schism in Washington and that Watson, the janitor he photographed, shared personal histories that complicated any reductive stereotype. The Atlantic, in a more recent piece, explicitly pushes against the ways Watson has sometimes been flattened into a symbol—insisting she had a story, and that Parks’ image is not a complete biography. That tension—between symbolism and individual life—haunts much documentary work. Parks’ strength was that he leaned into the tension rather than pretending it didn’t exist. His images could function as national allegory while still bearing the texture of a person’s particularity.

This is also where Parks’ aesthetic intelligence mattered. He was not a photographer who treated style as decoration. His sense of composition—his balance of light and shadow, his use of geometry, his control of pose—made his social critiques harder to dismiss. A sloppy image can be ignored as mere sentiment. A formally compelling image forces engagement. The National Gallery of Art notes the deliberateness of Parks’ self-portrait (1941), describing a careful composition that aligns his face with the camera lens, emphasizing vocation and contemplation. (National Gallery of Art) Even before his most famous work, he was already thinking about the photographer as subject: a Black man claiming authorship of his own gaze.

From Vogue to Life: Breaking barriers, then reshaping editorial power

Parks’ career is sometimes narrated as a sequence of historic “firsts,” but it’s more accurate to understand it as a series of negotiations with gatekeepers. He worked as a fashion photographer and broke into high-profile editorial spaces that were not built to accommodate Black authorship. By the late 1940s, his rise in magazine work culminated in something that would have been nearly unthinkable to many editors only a few years earlier: Parks became a staff photographer at Life magazine in 1948, where he produced work for more than two decades.

Life was not a neutral platform. It was one of the most influential visual storytellers in mid-century America, a magazine that helped build the country’s shared iconography. To be a staff photographer there was to shape not only what readers saw but how they were taught to interpret it. Parks’ significance is inseparable from that institutional reality: he became a Black author inside a machine that had long helped narrate America to itself.

This mattered in two directions. First, Parks’ presence in Life expanded who was allowed to speak in the visual language of mainstream America. Second, it created friction: Parks sometimes had to fight editorial framing that could twist a story toward sensationalism. TIME’s account of Parks’ Life work notes that an early essay, “Harlem Gang Leader,” initially carried an editorial slant that troubled Parks and helped drive his insistence on greater control in later projects. That is a crucial point for any honest evaluation of his career. Parks was not just a photographer for Life; he was often in contest with the magazine’s instincts—its appetite for spectacle, its tendency to simplify complex Black life for white readers.

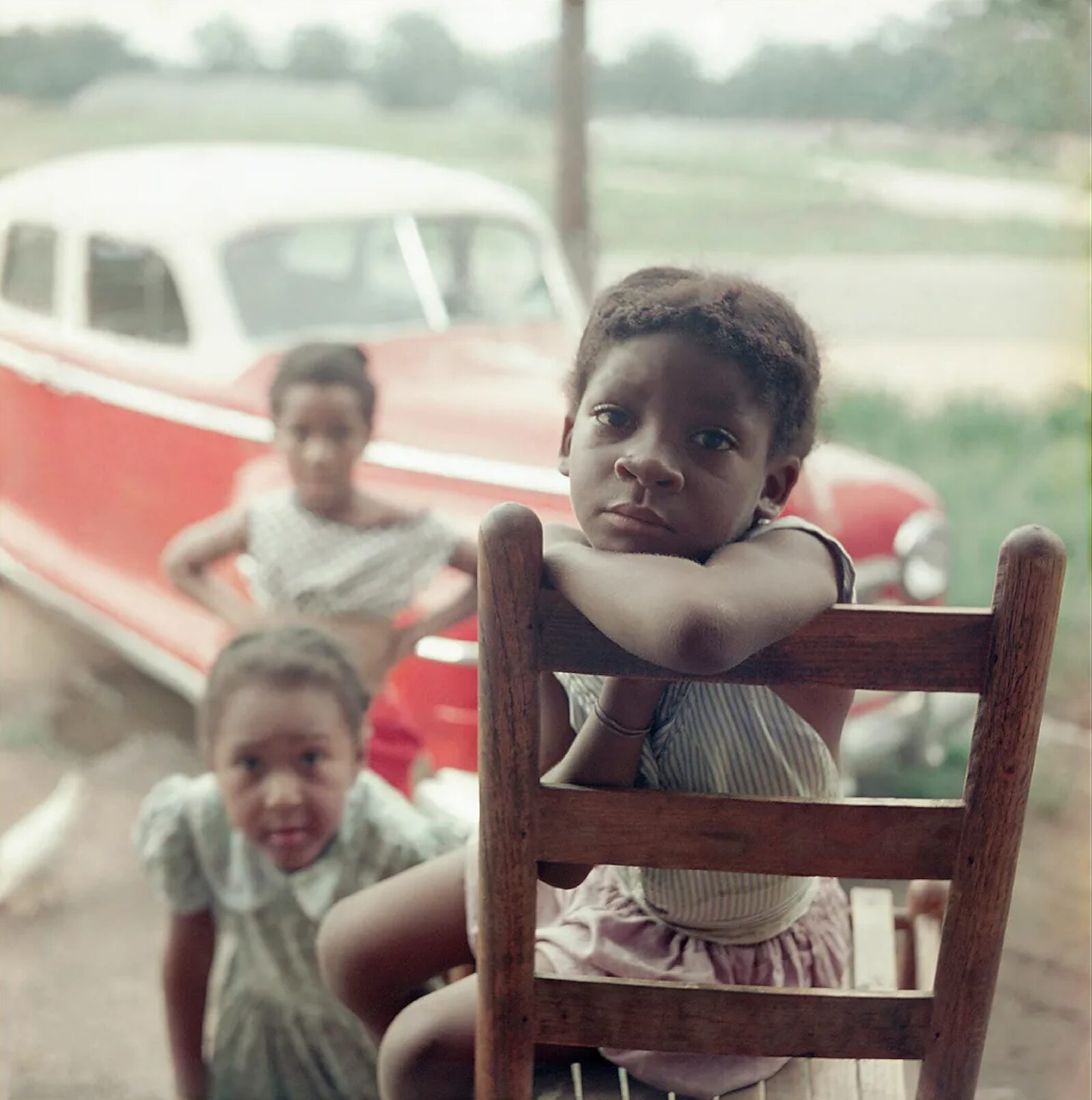

Parks’ solution was not withdrawal. It was authorship. Over time, he produced photo-essays that were more explicitly humane, less easily folded into stereotype. TIME highlights his later work portraying the Nation of Islam with nuance, countering prevailing media caricature, and his widely influential “A Harlem Family” essay about the Fontenelle family, which generated empathy and support from readers. The importance of those essays is not simply that they “raised awareness”—a phrase that can become a soft substitute for measurable impact. It’s that Parks used a mass-market magazine to force proximity: to make audiences sit with lives they might otherwise avoid, and to make inequality feel like something happening to people with names, rooms, routines, and grief.

At the same time, Parks’ fashion and portrait work demonstrated a different kind of intervention. The ability to photograph glamour—to render Black subjects as stylish, complex, and fully modern—was itself political in a culture that often restricted Black representation to labor, suffering, or caricature. Vogue’s coverage of a Gordon Parks exhibition emphasized his breadth: the show highlighted fashion photography and portraits alongside the better-known social-justice work, repositioning Parks as a master not only because of activism but because of aesthetic range.

This duality—Parks as witness to poverty and as maker of beauty—can confuse readers who want moral clarity to arrive without pleasure. Parks did not accept that trade-off. He seemed to argue, with his life, that beauty is not a distraction from justice; it is part of what justice promises.

“Born Black,” Paris, and the international relief of being un-caged

One of the more revealing aspects of Parks’ life is how often he sought—physically and artistically—to escape the American racial script, even as he remained committed to documenting it. His years in Paris are a telling example. While much popular memory anchors Parks in Harlem, Washington, or Hollywood, his work abroad suggests how profoundly geography can shift the felt experience of race.

A recent feature in Le Monde described Parks’ 1949–1951 period in Paris as a kind of mental liberation from the segregation of his home country, even as he remained attentive to the realities of colonialism and race in France. It notes he arrived as a photo correspondent for Life, photographed artists and street scenes, and formed connections with other Black American artists in France, such as James Baldwin. Even filtered through another publication’s lens, the significance is clear: Parks’ international work complicates the idea that he was only a “civil-rights photographer.” He was also a cosmopolitan artist mapping freedom and constraint across borders.

Ebony’s more recent reporting on exhibitions like “Born Black” underscores how institutions continue to reframe Parks’ work as a long arc of Black experience—history, daily life, struggle, dignity—rather than a set of isolated iconic images. That ongoing curatorial attention is itself evidence of Parks’ layered legacy: his archive is expansive enough to sustain new readings in new political moments.

Writing, music, and the insistence on being uncontainable

Parks’ photographic fame can overshadow how seriously he took his other forms. But he was not dabbling. He wrote books, including memoir and fiction; he composed music; he directed films and even scored at least some of them. The Gordon Parks Foundation biography explicitly foregrounds this: Parks was not only a photographer but also a distinguished composer, author, and filmmaker who interacted with leading political and cultural figures across decades.

That multiplicity is not trivia. It’s a clue to how he understood power. Different platforms reach different audiences. A photograph in Life can enter millions of homes and fix an image in the national imagination. A novel can explore interiority—what photographs can only suggest. A film can reshape mass desire and identification, teaching audiences who can be heroic, seductive, complex, or morally ambiguous. Parks’ decision to work across mediums reads less like restlessness and more like strategy: he refused to let his message be limited by a single gatekeeping system.

This is also where the phrase often associated with Parks—“a choice of weapons,” the title of his memoir—lands with full force. The “weapon” is not violence. It is craft. It is the deliberate selection of tools that can penetrate denial.

Hollywood: The Learning Tree and the politics of authorship

Parks’ move into filmmaking could have been treated as a career pivot; instead, it functioned as a continuation of the same project. In 1969, he wrote, produced, directed, and scored The Learning Tree, adapted from his semi-autobiographical novel, a coming-of-age story set in Kansas. The film is widely described as the first major studio film directed by a Black filmmaker, produced through Warner Bros.-Seven Arts—an industry fact repeated across reference sources and highlighted in later retrospectives.

The “first” matters, but the deeper significance lies in what that “first” required: a major American studio entrusting a Black artist not merely with a niche project but with full authorship—direction, writing, and production responsibilities. It also meant Parks had to translate his sensibility into a different industrial language. Film is collaborative; it is expensive; it is policed by executives and distributors. Parks’ success in getting such a film made suggests not only talent but persuasion, stamina, and an ability to navigate systems that were not designed for him to control them.

The Guardian’s later reflection on Parks notes the breadth of his talents even at the time: a Life photographer, writer, composer, and the first Black film director and producer, forged by tough experience. That toughness wasn’t simply personal grit. It was a learned capacity to withstand misreading—especially the misreading that comes when a Black artist works inside white institutions that want either uplift without discomfort or critique without glamour.

Shaft: Mainstream success, controversy, and a new kind of Black hero

If The Learning Tree established Parks as a filmmaker with studio backing, Shaft (1971) made him a director associated with commercial and cultural earthquake. The film introduced Richard Roundtree as John Shaft, a Black private detective whose cool, competence, and sexuality were not coded as subservient or comedic. The Isaac Hayes theme became iconic and won an Academy Award, embedding the film into the era’s sound as well as its visual style.

The success of Shaft is often folded into the shorthand of “blaxploitation,” a term that has always carried contested meanings: celebration for opening doors and centering Black leads, criticism for reinforcing stereotypes and commodifying Black urban life for profit. Parks’ relationship to that label was wary. The Guardian obituary explicitly notes that Parks avoided the “black exploitation” label even as the genre formed quickly around the film’s impact.

Here, Parks’ significance is not reducible to whether Shaft “helped” or “hurt” representation in some single, final way. The more precise argument is that Parks expanded the range of what was possible in mainstream American cinema, then had to live with what markets did to that expansion. He proved that Hollywood had underestimated Black audiences and Black-led stories—a point the Guardian later revisited in a piece discussing how The Learning Tree and Shaft broke new ground and influenced subsequent Black-centered filmmaking. Once Hollywood understood the profit potential, it moved fast, often without nuance.

This is a recurring pattern in American culture: a Black artist pushes open a door with craft and risk; an industry rushes in after with replication and dilution. Parks’ achievement was opening the door while still trying to keep authorship—still trying to insist on dignity and complexity—even when the marketplace preferred easy tropes.

Ethics in the frame: What Parks demanded of viewers

Parks’ body of work invites a question that is also an ethical test: what is the responsibility of the viewer? Documentary images can become a kind of consumption—poverty as spectacle, racial pain as content. Parks seemed aware of that danger. One reason his work remains potent is that it rarely lets the viewer off the hook. His images often contain a moral reciprocity: you are looking, but you are also being positioned as someone who must answer for what you see.

This is especially clear in the endurance of American Gothic and in the continued scholarship around it. The Gordon Parks Foundation’s publications emphasize the photograph’s influence and the depth of inquiry it continues to generate, including contributions from scholars and curators who treat the image not as a frozen symbol but as a site of ongoing interpretation. The Atlantic’s insistence that Ella Watson was not a stereotype—“no ‘mammy’”—is part of that corrective work, reminding audiences that the subject of a famous image can be erased by fame itself.

The ethics extend to Parks’ broader Life work. TIME’s analysis of his photo-essays underscores how he pushed for control over narrative framing, resisting editorial distortions and seeking fuller portrayals of communities that magazines often reduced to pathology. If you want a simple moral of Parks’ career, it might be this: representation is not only who is shown; it is who controls the terms of showing.

Legacy: Institutions, archives, and the next generation

After Parks’ death in 2006, his legacy did not simply settle into museum walls. It became active infrastructure. The Gordon Parks Foundation—created to preserve his work and support artistic and educational activities—frames its mission as advancing what Parks described as “the common search for a better life and a better world.” The existence of such a foundation matters for reasons beyond philanthropy. Archives determine what stories remain available for reinterpretation. Grants and fellowships determine who gets resources to keep making.

Parks’ influence is visible not only in exhibitions but in acquisitions and collections that treat his work as essential to American art history. The Root reported on Howard University receiving a major collection of Parks photographs—more than 250 images spanning decades—describing it as a comprehensive holding that would showcase the breadth of his career. Even if one treats the superlatives with caution, the underlying fact is significant: Parks is being institutionalized within historically Black educational spaces as well as mainstream museums, reinforcing his dual role as a national artist and a specifically Black cultural ancestor.

The Washington Post, writing in 2022 about Parks’ legacy, argued that his impact remained potent and expansive, emphasizing how his work explored inequality and poverty in ways that still haunt the present. This is perhaps the most sobering measure of his relevance: Parks’ images are not relics because the conditions they document—segregation’s afterlives, structural poverty, racialized surveillance, the fragility of Black safety—have not vanished. His work continues to feel contemporary not because it is trendy, but because America keeps re-enacting variations of the same injustices.

Why Gordon Parks still matters now

The risk in praising Gordon Parks is turning him into a saintly abstraction: the benevolent artist who “gave voice,” “shined a light,” “raised awareness.” Parks deserves more exact language. He was a maker who understood that American life is contested terrain and that images are among the tools used to control that terrain. He insisted on Black humanity with a precision that included both suffering and style, both structural critique and intimate tenderness. He used mainstream platforms without being fully tamed by them.

His career also presents a model that remains instructive for artists and journalists working now. Parks did not accept the false choice between aesthetics and ethics. He demonstrated that beauty can be a delivery system for truth, and that truth can be sharpened by formal excellence. He learned how institutions functioned and then used their scale to circulate stories they might otherwise have excluded. He fought for narrative control when editorial framing threatened to turn people into caricatures. And when the magazine page was not enough, he moved to the novel and the film screen.

In a moment when images circulate faster than reflection—when suffering can be monetized as virality, when representation is debated as branding—Parks’ work offers a tougher standard. His photographs do not ask for attention as charity. They demand attention as recognition. They do not request sympathy without accountability. They argue that to see is to become responsible.

That is the deep continuity across his mediums. Whether he is photographing Ella Watson before a flag, rendering fashion with kinetic grace, capturing the complicated lives of Harlem residents, or directing a detective who refuses to shrink himself for anyone’s comfort, Parks is making the same claim: Black life is not a sidebar to the American story. It is the American story—seen in full, without permission, and without apology.

More great stories

The Kissing Case: How a Child’s Game Became a Jim Crow Trial of Power