The most important way to honor Gravely is not merely to recite his firsts. It is to understand what those firsts meant operationally.

The most important way to honor Gravely is not merely to recite his firsts. It is to understand what those firsts meant operationally.

By KOLUMN Magazine

There are a few kinds of American “firsts.” Some are loud—momentary ruptures that the culture immediately knows how to narrate. Others are quiet, procedural, stitched into the daily machinery of institutions that don’t like to confess they are changing until the change is irreversible. Samuel L. Gravely Jr. belongs to that second tradition: a man whose breakthroughs were not staged for cameras, but executed on watch bills, on underway schedules, and in a chain of command that had to be persuaded—again and again—that authority could wear his face.

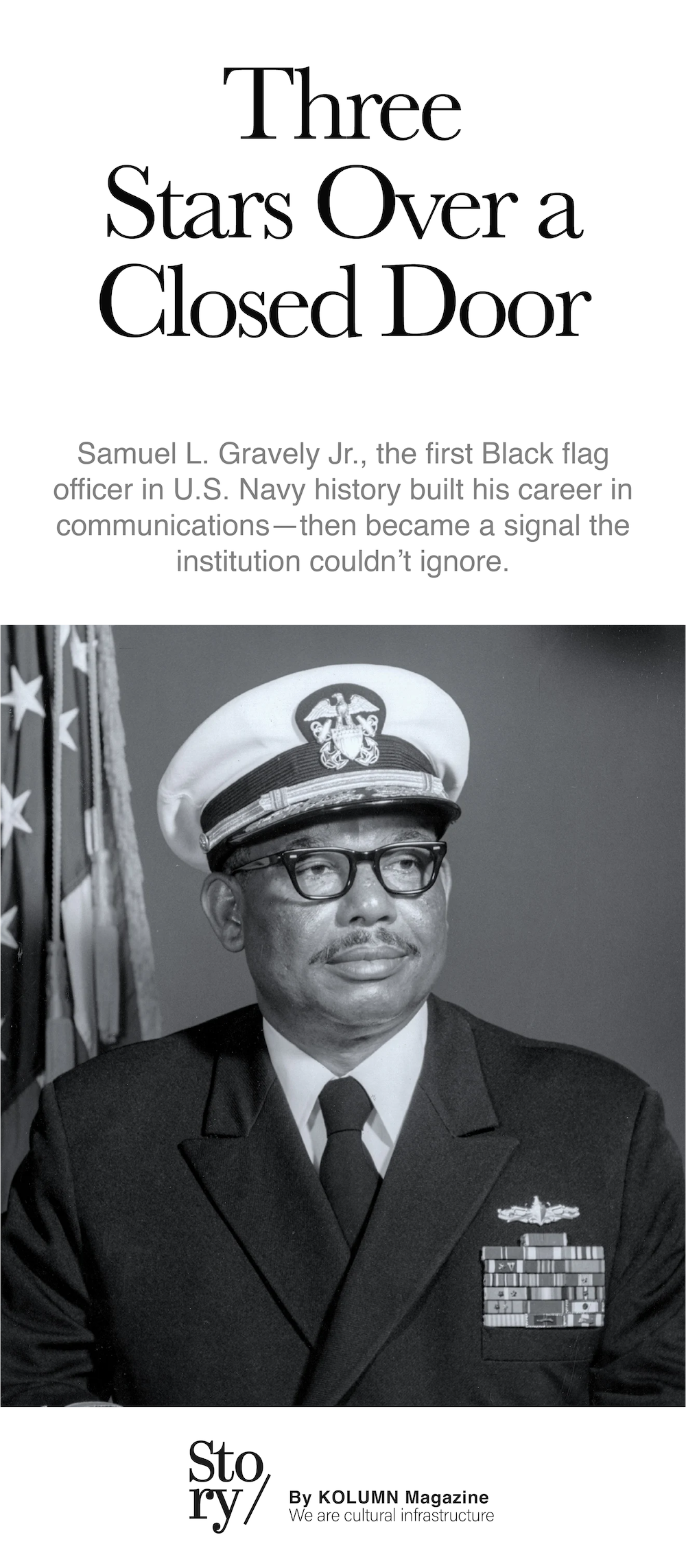

By the time he retired as a vice admiral, Gravely had accumulated a resume that reads like a set of locked doors forced open with patience: the first African American in the U.S. Navy to serve aboard a fighting ship as an officer; the first to command a Navy ship; the first to become a flag officer; the first to command a fleet. Those milestones are often repeated as a list, as if their meaning is self-evident. But the story of Gravely’s life—what it cost, what it required, what it changed—lives in the space behind each “first,” where the institution’s resistance sits.

He came of age in a country that could imagine Black service more easily than Black command. In the early 1940s, the Navy still largely confined African Americans to steward and messman roles. The officer corps was overwhelmingly white; the idea of a Black man issuing orders on the deck of a warship was, to many in the service, a provocation. The pressure that would define Gravely’s career was not merely personal ambition or professional excellence—though both were abundant—but the knowledge that in such a system, a single misstep could be generalized into an argument against everyone who might follow.

Years later, in reflections about his career, he would articulate a sentiment that historians, veterans, and family members have repeated in various forms: he understood that failure would not be allowed to remain individual. It would be made representative. That awareness is not melodrama; it is an occupational hazard of being first.

To tell Gravely’s story with journalistic integrity is to resist flattening his achievements into inspirational slogans. It is also to recognize what his career reveals about American institutions: how they evolve, how they protect themselves, and how, under pressure—political, military, moral—they sometimes yield. His life moves through three eras that transformed the U.S. armed forces: World War II, when the contradictions of fighting fascism abroad while maintaining segregation at home grew too glaring to contain; the early Cold War, when the question of integration became a question of national credibility; and Vietnam, when leadership and legitimacy were under strain and the officer corps was forced, slowly, to change.

Gravely’s story is not only a Navy story. It is an American story about professionalism as a form of protest, about endurance as a strategy, and about how a man can become a bridge—crossed by others—without ever being thanked by the institution while he is building it.

Richmond beginnings and a nation’s limits on Black ambition

Samuel Lee Gravely Jr. was born in Richmond, Virginia, in 1922—a city heavy with Confederate memory and the social architecture of Jim Crow. If his later life would become a narrative of breaking barriers, his early life was a lesson in how those barriers were built: through law, custom, and the daily signals of who could expect to be listened to.

He attended Virginia Union University, one of the historically Black colleges that served as both refuge and engine—producing professionals and civic leaders in a segregated society that offered too few routes into power. Like many young men of his generation, Gravely’s education was interrupted by war. In 1942, with World War II reshaping the lives of Americans in every region, he entered the Naval Reserve.

The choice matters. The Navy, even as it expanded rapidly for war, was not widely seen as hospitable terrain for Black advancement. The Army, though segregated, had its own traditions of Black units; the Navy’s traditions were different, often more restrictive in the roles it assigned. Yet Gravely went anyway, stepping into an institution whose boundaries were being contested by Black Americans, civil rights leaders, and, increasingly, the demands of the war itself.

In 1944, the Navy commissioned the “Golden Thirteen,” the first African American commissioned and warrant officers in the service’s history. Their commissioning was both a breakthrough and a contained experiment—an acknowledgement of capability paired with an impulse to limit its consequences. The Golden Thirteen excelled in training, but many were still steered into marginal assignments, their success treated as inconvenient evidence rather than a catalyst for full inclusion.

Gravely’s path into officership ran through another wartime program: the Navy V-12 College Training Program, designed to produce officers quickly. He trained, advanced, and was commissioned at a moment when the Navy’s racial policies were beginning to crack—under pressure from manpower needs, public scrutiny, and the broader fight for civil rights at home.

But “cracking” is not the same as “opening.” When Gravely stepped into the officer corps, he did so as a rarity, and rarities are watched. His competence would be evaluated with intensity; his mistakes would be remembered with enthusiasm. That burden, while never officially stated, shaped how he navigated the institution. In oral histories and biographical accounts, Gravely’s story returns again and again to discipline, preparation, and the careful management of perception—skills that were not merely about success but about survival.

PC-1264 and the wartime experiment that foretold his future

To understand what Gravely became, you have to look at where he served when the Navy was still deciding what it would allow. One of Gravely’s formative assignments was aboard USS PC-1264, a submarine chaser whose crew composition made it extraordinary. PC-1264—along with USS Mason—became part of the Navy’s wartime experiment in employing predominantly Black enlisted crews outside of servant roles.

The existence of that experiment is itself an indictment of the era’s assumptions. The Navy did not integrate because it suddenly discovered equality; it integrated in controlled doses because the old policies were increasingly indefensible and impractical. The performance of those ships forced reevaluation. Official historical accounts and archival discussions have emphasized how PC-1264 and Mason demonstrated, in operation, what Black sailors could do when allowed to do Navy work—repair, fight, patrol, perform under pressure.

Gravely’s presence on PC-1264 also placed him inside a contradiction: he was an officer in a ship whose enlisted men were largely Black, in a Navy that still treated Black authority as anomalous. That environment offered both opportunity and weight. Opportunity, because competence could be demonstrated in the most concrete way: a ship that performs its missions. Weight, because ships like PC-1264 were read symbolically. Their success mattered beyond their tonnage.

In the National Archives’ discussion of PC-1264 and Mason, the point is blunt: these ships, by doing their jobs well, helped force the Navy to reconsider discriminatory policy. It is difficult to imagine Gravely not learning something essential there: that institutional change sometimes comes less from argument than from undeniable performance. Run the ship. Make the mission happen. Leave no excuse.

He carried that lesson through a career that would make him the institutional proof point the Navy could no longer ignore.

The postwar Navy, recall to duty, and the slow mechanics of integration

World War II ended, but the American military’s racial structure did not disappear overnight. Gravely was released from active duty in 1946, remained in the Naval Reserve, and returned to civilian life and education, ultimately completing his degree at Virginia Union University.

Then the Navy called him back. In 1949, he was recalled to active duty, working in recruiting and continuing his naval path as the Cold War hardened. This period matters because it shows how integration in the U.S. military was less a single event than an extended process: a policy shift, then a long operational negotiation.

In July 1948, President Harry S. Truman issued Executive Order 9981, declaring equality of treatment and opportunity in the armed forces without regard to race, color, religion, or national origin. The order is often taught as a clear line: before segregation, after integration. The reality, as historians of military integration have long noted, is more uneven. The order created direction; it did not instantly change culture. Resistance persisted, sometimes openly, often quietly—through assignments, evaluations, social pressure, and the friction of traditions that die slowly.

Gravely’s career unfolded inside that long aftermath. The Korean War, where he served aboard USS Iowa as a communications officer, became one of the conflicts in which the military’s integration policies were tested in practice. War has a way of making performance the final argument. But it also exposes hypocrisy: a nation willing to demand sacrifice from Black servicemembers while still limiting their advancement.

During these years, Gravely began specializing in naval communications—a discipline that would become central to his identity and later command roles. Communications is sometimes treated as a technical specialty, but in modern navies it is also strategic: the ability to connect ships, commands, and decision-makers; the ability to control information flow; the ability to coordinate complex operations. To become an expert there was to place oneself near the nervous system of the institution.

It also positioned Gravely in a domain where excellence could be measured, and where credibility could be built through mastery. In a Navy where some people might still question whether he “belonged” on the bridge, communications expertise offered a different route to indispensability: make yourself the person the system needs in order to function.

Command begins: The bridge, the burden, and the meaning of authority

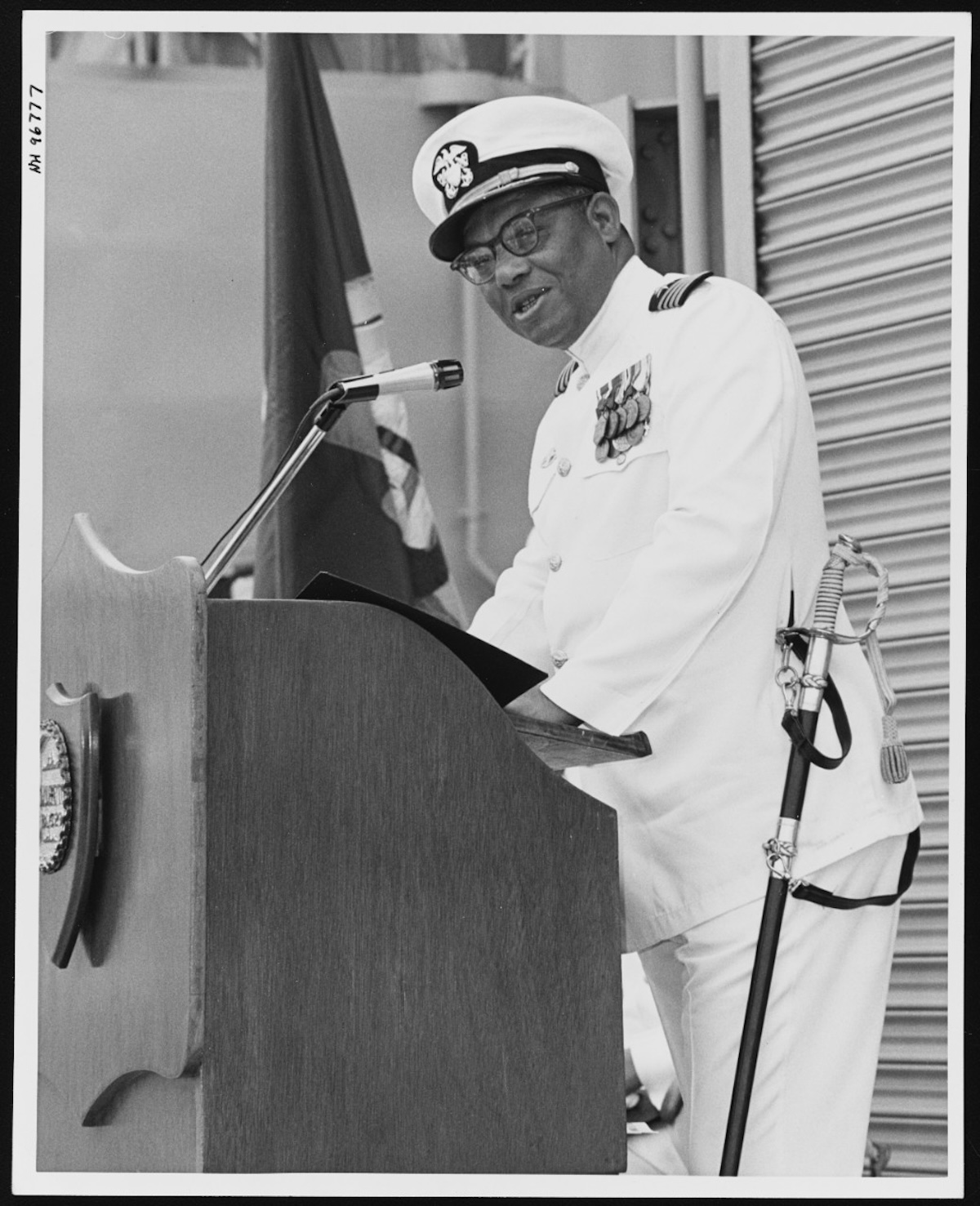

Gravely’s ascent into command was not merely a personal triumph. It was a structural event. In 1961, he became the first African American officer to command a U.S. Navy ship—serving as acting commanding officer of USS Theodore E. Chandler. The moment can be framed as symbolic, but within the Navy, command is not symbolism. Command is authority backed by law, tradition, and the trust of the institution. To give a man command is to declare, officially, that his judgment will be obeyed.

By the early 1960s, the civil rights movement was forcing the country to confront its public contradictions. Sit-ins, Freedom Rides, the growing visibility of Black political struggle—all made it harder for federal institutions to present segregation as a local custom. The Navy, like other branches, was aware of the optics of integration, but it was also aware of operational reality: the service needed talent, and it needed officers capable of navigating a changing world.

Gravely’s command of USS Falgout, a radar picket destroyer escort, followed soon after, marking him as not a one-time exception but a continuing precedent. These were not ceremonial roles. They were sea commands in an era when the U.S. Navy was deeply engaged in Cold War posture—presence, surveillance, readiness, and the kind of constant movement that makes command both exhausting and clarifying.

It is here that Gravely’s story begins to show its deeper significance. Many institutions can tolerate a first if they treat it as an anomaly—a figure to display, then shelve. Gravely did not allow that. His career continued, his competence accumulated, and the Navy had to either promote him or explicitly declare that the ceiling remained. In a bureaucracy that prefers quiet solutions, promotion became the path of least resistance—provided, of course, that the man was unimpeachably good at his job.

Gravely appears to have understood that dynamic. His ethic, as described in oral histories, biographical sketches, and commemorations, emphasized preparation and perseverance—qualities that are often praised as individual virtues but, in his context, functioned as political tools. In a system where his legitimacy could be questioned, he constructed legitimacy through relentless professionalism.

Vietnam and the difference between “command” and “combat”

If the early 1960s established Gravely as a commander, Vietnam tested what that meant under fire. During the Vietnam War, he commanded the destroyer USS Taussig, which conducted missions including plane guard duty and naval gunfire support off the coast of Vietnam. Accounts of his career emphasize that this made him the first African American to lead a ship into combat.

The difference between commanding a ship in peacetime and commanding in wartime is not only the possibility of casualties; it is the way wartime amplifies judgment. The consequences of decisions become immediate. A navigation error is no longer an embarrassment; it can become disaster. A communications failure can mean friendly-fire incidents or missed opportunities. Command becomes a crucible in which leadership is judged not by style but by outcome.

For a Black officer in that era, the stakes were multiplied. A white commander’s failure could be individualized; a Black commander’s failure could be turned into a “lesson.” Gravely’s performance in Vietnam-era command helped destroy that easy narrative. It is not that racism disappeared; it is that the institution’s ability to justify exclusion became harder.

The Navy also used Vietnam as a stage for modernization—new systems, new weapons, evolving doctrines. Gravely’s background in communications positioned him well in this environment. He served as coordinator of the Navy’s satellite communications program, reflecting how his expertise aligned with the service’s technological trajectory. In other words: he was not only breaking racial barriers; he was working in the domains the Navy considered central to its future.

That is part of his significance: Gravely’s story is not simply about inclusion in the abstract. It is about the relationship between inclusion and institutional competence. When a Navy excludes talent for racial reasons, it harms itself. Gravely’s career became evidence of what the institution gained when it stopped denying itself.

Flag rank and the moment the Navy could no longer pretend

In 1971, while commanding USS Jouett, a guided missile destroyer leader, Gravely was selected for flag rank—becoming the first African American rear admiral in the U.S. Navy. Promotions to flag rank are not merely career milestones; they are decisions about who gets to shape the service’s direction. The leap from captain to admiral is the leap from executing policy to making it.

Flag rank also changes visibility. A Black commander can be treated as unusual; a Black admiral cannot be dismissed so easily. Admirals are institutional faces. Their presence forces the institution to answer, implicitly, questions about who is considered capable of strategic leadership.

Gravely’s subsequent commands and senior roles included positions tied directly to communications and operational leadership, such as Naval Communications Command and later fleet-level responsibilities. These were domains of high trust. In the Navy, trust is the currency of advancement; you can’t command fleets if the institution does not believe you can manage complexity and risk.

In 1976, Gravely became Commander, Third Fleet—based in Hawaii—and with that assignment he was promoted to vice admiral, another “first.” Third Fleet is not a token command. It is central to Pacific operations and readiness, a place where presence and preparation shape America’s posture in an ocean that has long been strategic theater.

To say Gravely commanded Third Fleet is to say the Navy entrusted him with one of its most significant operational formations. It is also to note how far the institution moved—slowly, reluctantly, but unmistakably—from the era when Black sailors were expected to serve meals to the era when a Black officer could command the fleet.

That transition did not occur because the Navy became morally enlightened. It occurred through pressure from outside—the civil rights movement, federal policy, international scrutiny—and through people inside, like Gravely, who made the old justifications impossible to sustain.

The Defense Communications Agency and the meaning of “infrastructure” power

In his final major assignment, Gravely served as director of the Defense Communications Agency (DCA) from 1978 until his retirement in 1980. DCA—historically tied to defense-wide communications—represented a different kind of command. It was joint, strategic, and infrastructural. It required navigating not only Navy culture but inter-service politics and the broader defense bureaucracy.

This is where Gravely’s long specialization in communications resolves into a final statement. Throughout his career, he had positioned himself near the systems that connect power: the networks that allow commands to coordinate, the protocols that govern information, the architecture that makes modern military operations possible. To lead such an agency was to lead the invisible structure under the visible force.

For a Black officer who had begun his career in a segregated institution, that arc is profound. Gravely went from fighting for a place on a ship to running a key part of the military’s connective tissue.

It also reveals something about how institutions sometimes allow change: they may resist symbolic inclusion, but they often cannot resist competence in the domains that matter to their survival. Gravely’s career exploited that reality—not cynically, but strategically. He built a professional identity that intersected with the Navy’s evolving needs. And in doing so, he made himself, in effect, non-optional.

The personal life behind public breakthroughs

Obituaries and official biographies often mention the basics: Gravely married Alma Bernice Clark; they raised a family; he lived in Haymarket, Virginia in retirement; he died in 2004 after a stroke and was buried at Arlington National Cemetery. The facts are important, but they can also obscure the human costs of a life lived under constant scrutiny.

To be “first” is to live with relentless visibility while often being denied full belonging. Gravely navigated a Navy that, for much of his career, did not offer Black officers the same social ease that white officers took for granted. Even when policy changed, culture lagged. Integration on paper did not always mean integration in messes, in housing patterns, in mentorship networks.

This is why oral histories matter. In recorded recollections, Gravely’s career is not simply a set of promotions; it is a long negotiation with an institution’s assumptions, carried out through calm persistence.

There is also the question of what he chose not to do. Some pioneers become public crusaders, denouncing institutions loudly. Gravely’s method was different. He worked inside the system, reshaping it through performance and presence. That strategy has its own costs: the need to bite one’s tongue, the need to stay composed under insult, the need to remain “professional” even when the institution is not.

But it also has results. Gravely’s advancement created precedents that later officers could use as leverage. Once a man has commanded a ship, arguments that “it can’t be done” are harder to make. Once a man has held flag rank, the notion that leadership is racially bound becomes absurd.

Legacy: USS Gravely, civic memorials, and the danger of turning a life into a slogan

If you want to see how the Navy remembers Samuel L. Gravely Jr., look at what bears his name. USS Gravely (DDG-107), an Arleigh Burke–class guided missile destroyer, is named in his honor. In the Navy, naming is not mere tribute; it is canonization. It means the institution has decided this person embodies the values it wants to project forward.

There are other memorials as well: a school in Virginia named for him; commemorations and educational events that emphasize his motto of “Education, Motivation, Perseverance”; celebrations aboard the Battleship Iowa Museum that frame his life as a model of leadership and service.

But remembrance has a risk: it can sanitize. Institutions are skilled at celebrating pioneers without fully confronting what made their pioneering necessary. It is easier to honor Gravely as an inspirational figure than to reckon with the Navy that restricted Black sailors to servant roles, or the slow-walked integration that required federal intervention. It is easier to turn his life into a motivational poster than to admit that he succeeded in spite of the institution’s resistance.

A more honest legacy narrative would hold both truths at once: the Navy produced and benefited from Gravely’s leadership, and the Navy also forced Gravely to carry burdens his white peers did not. His career is a testament to individual excellence and a case study in structural constraint.

It is also, importantly, a story about how change becomes durable. Gravely did not simply break one barrier; he broke several, in sequence, in ways that created institutional memory. A “first” can be forgotten; a chain of “firsts” becomes a new baseline.

This is why his significance extends beyond the Navy. In American life, progress is often measured in symbolic moments. But institutions change through process—through who gets trained, who gets promoted, who gets trusted. Gravely’s life was a process story: a slow conversion of exclusion into precedent.

What Samuel L. Gravely Jr. reveals about America’s institutions

To write about Gravely in the present tense is to confront a question that never goes away: what does it mean to be included in an institution that was built with your exclusion in mind? Gravely’s answer appears to have been pragmatic and uncompromising: master the craft, accept the burden, widen the path.

His career also forces a more complex view of “integration.” Executive Order 9981 set a moral and legal direction, but it did not guarantee lived equality. Progress required people inside the system who could embody competence so clearly that resistance became costly.

That is a hard model to celebrate, because it places the burden on the excluded to prove their worth in a system that should never have doubted it. Yet that is the model history often reveals. Gravely’s life is a reminder that institutions rarely grant equality freely. They are forced—by law, by politics, by war, by the quiet accumulation of evidence.

The most important way to honor Gravely is not merely to recite his firsts. It is to understand what those firsts meant operationally. The bridge of a ship is not a stage. It is the place where orders become action, where lives can depend on judgment, where leadership becomes visible in the most unforgiving way. Gravely stood there, again and again, and the institution had to accept what it saw.

When he died in 2004, obituaries framed him correctly: as the Navy’s first Black admiral, a man who had commanded fleet forces and rewritten the boundaries of who could lead. But the deeper truth is that he did something even more difficult than becoming “first.” He made “first” repeatable—turning an anomaly into a lineage.

That is the kind of change that lasts.

More great stories

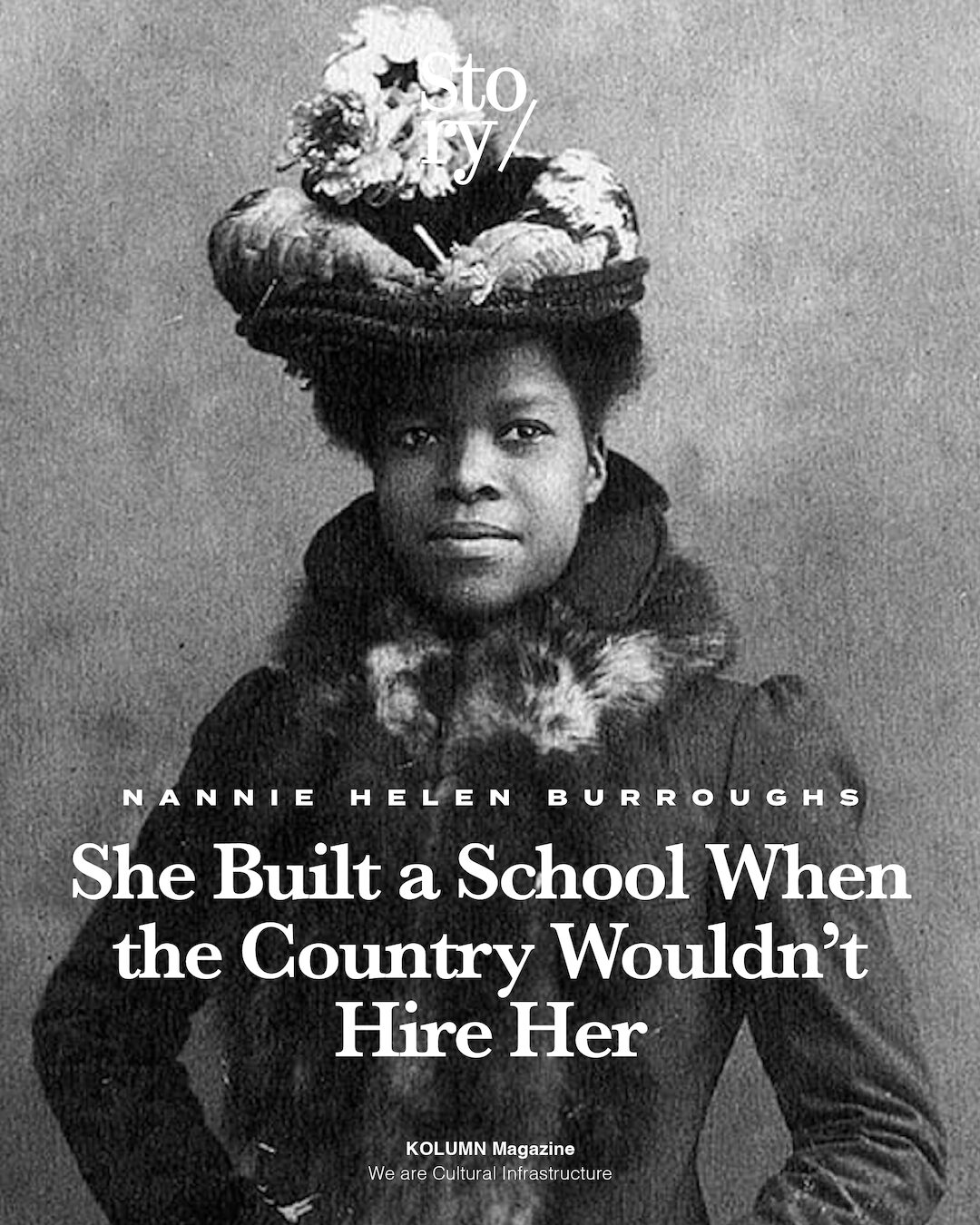

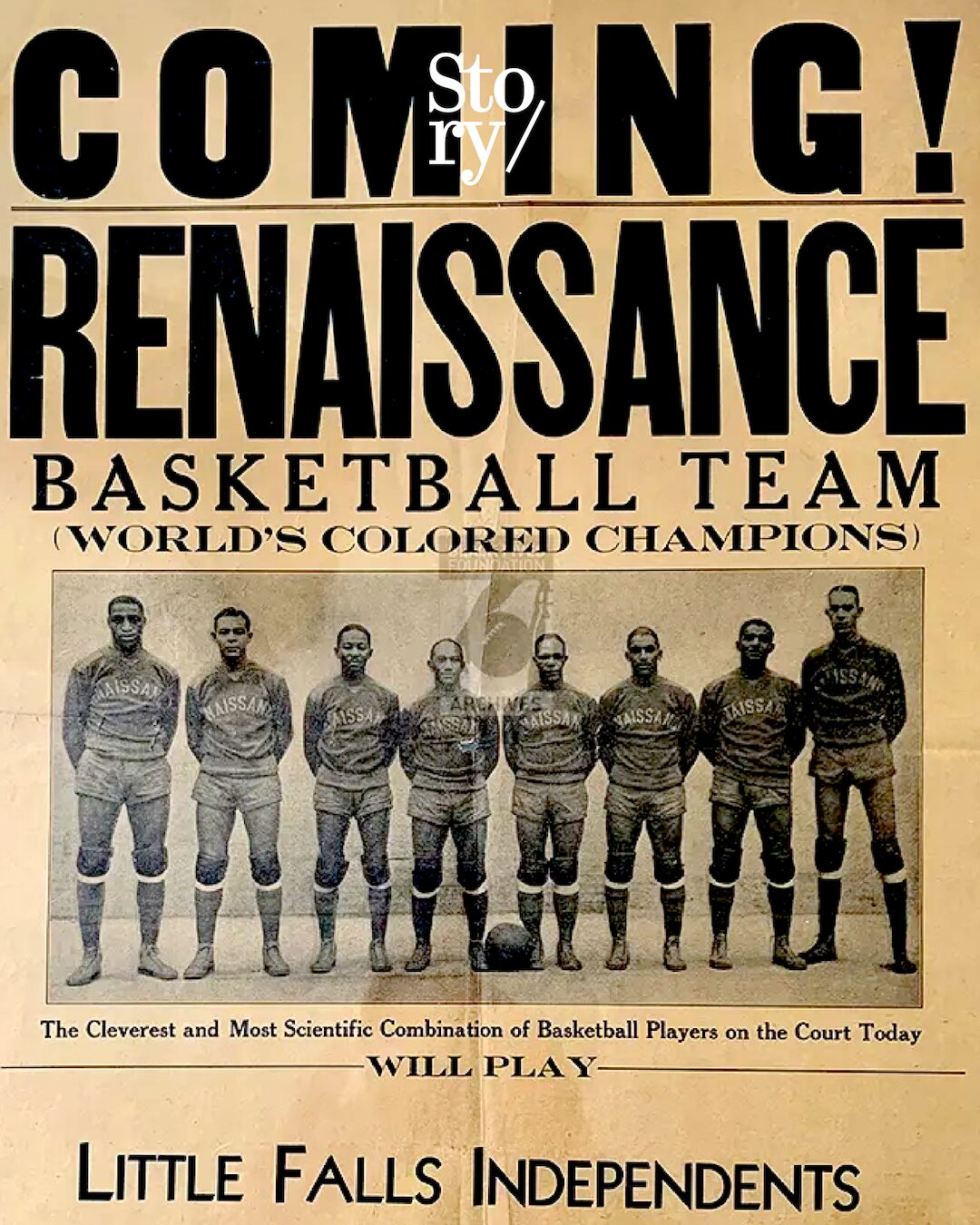

The Greatest Team You Never Saw