The Negro National League cannot be reduced to an athletic milestone. It was a form of collective economic self-defense

The Negro National League cannot be reduced to an athletic milestone. It was a form of collective economic self-defense

By KOLUMN Magazine

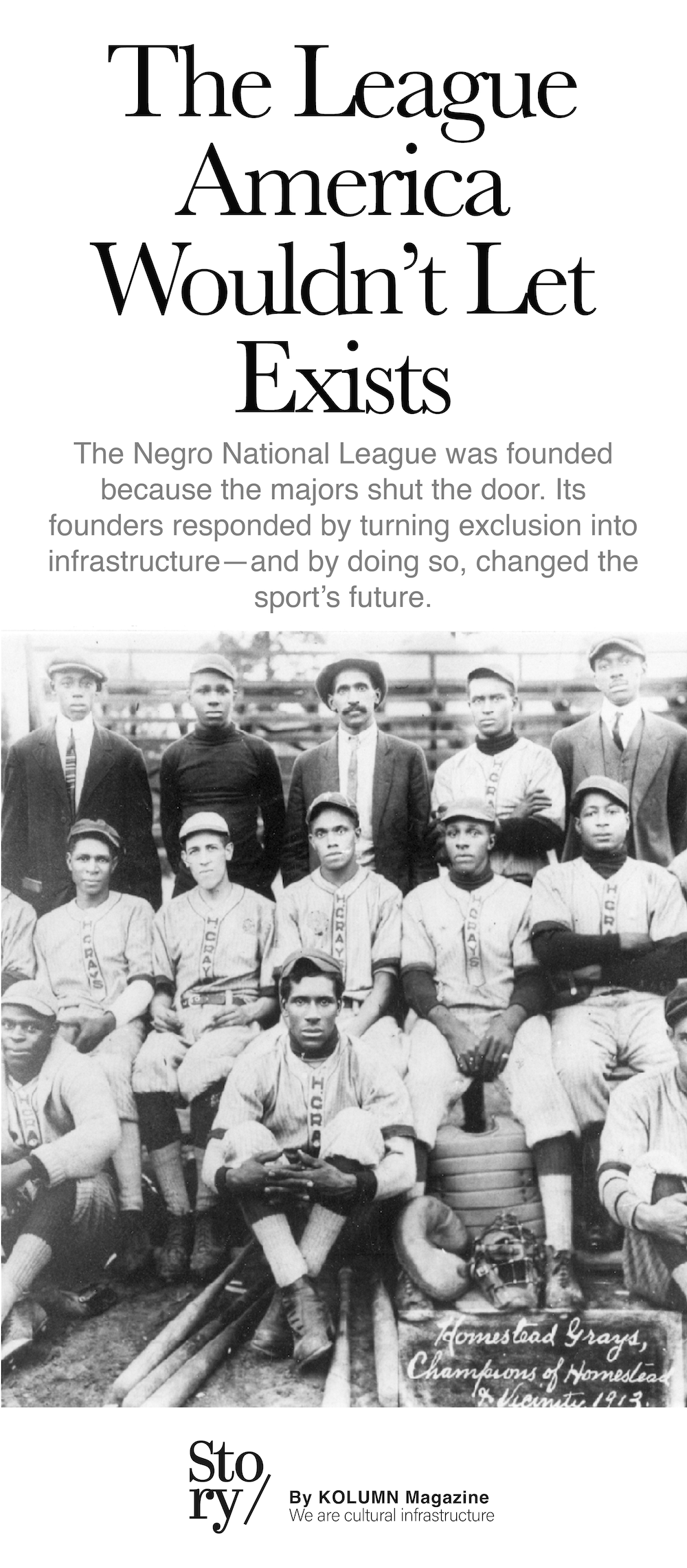

If you wanted to find the birth certificate of the Negro National League, you would not start with a stadium or a trophy case. You would start with a building more associated with community programs than with pennant races: the Paseo YMCA in Kansas City, Missouri. There, on February 13, 1920, a coalition of Black team owners and baseball executives gathered to do something that read, at the time, like both common sense and audacity—agree to bind themselves to a shared schedule, shared rules, and a shared business framework in a country whose most powerful baseball institutions were binding themselves to the opposite project: the maintenance of a color line.

The decision they made—forming what was then called the Negro National League (and sometimes referenced in period and later writing as the National Negro League)—has often been retold as a sports story: visionary organizer, struggling franchises, barnstorming legends, packed grandstands. It is all of that. But the deeper significance of the league is that it functioned as something like municipal governance for a mobile nation within a nation. In the absence of equal access to white-owned professional baseball, the league’s founders built an alternative system that combined commerce, entertainment, labor organization, travel logistics, media production, and—crucially—public memory.

The central figure in this origin story is Andrew “Rube” Foster, owner and manager of the Chicago American Giants and, by wide consensus among historians, one of the most important architects in Black baseball history. Foster spent years arguing that organization was not merely a preference but a necessity, pressing fellow owners toward a structure sturdy enough to withstand the sport’s constant threats: predatory contracts, schedule chaos, unreliable payments, and the ever-present vulnerability that came from operating in segregated markets where access to venues, rail lines, and capital could change overnight.

Foster’s push was practical—stability meant money—and ideological—stability meant independence. The league adopted a motto that worked as both poetry and policy, borrowed from Frederick Douglass: “We are the ship, all else the sea.” In that phrasing is the league’s core assertion. The sea was not only competition; it was a social order. To be “the ship” was to be self-propelled, navigational, and governed by Black decision-making rather than white permission.

The meeting at the YMCA did not instantly dissolve the problems of Black baseball. It could not. Even the league’s internal politics became contentious at times—Foster’s power as league president and as owner-manager of a flagship club led to criticisms that the structure favored his team in scheduling and talent acquisition, accusations that echo a familiar pattern in American sports: centralization creates stability, and stability creates arguments about fairness.

But the fact that such arguments could happen within a Black-run league is part of the story. You cannot accuse an institution of favoritism unless it exists long enough—and seriously enough—to accumulate power worth disputing. In that sense, the Negro National League’s achievement was not only the games it staged, but the durable administrative reality it created. The Baseball Hall of Fame frames the league’s creation as a turning point that proved Black players could perform at the highest levels and draw serious crowds, undermining one of segregation’s most persistent lies: that exclusion was merely a matter of “quality” or “fit,” rather than policy.

The context: Segregated baseball, a “gentlemen’s agreement,” and the building of parallel worlds

Any account of the Negro National League’s founding that treats it as a stand-alone innovation risks misunderstanding its cause. The league was, in the most direct sense, a response to enclosure. By the early 20th century, Black players had been pushed out of white professional baseball through a “gentlemen’s agreement” among white owners—an informal mechanism that functioned like law because it was enforced by shared interest and shared prejudice. The Atlantic’s essay on the documentary The League notes that Black Americans had played on major-league teams as early as the 1880s, but that by World War I, the door had been effectively shut, forcing Black players and executives to develop their own professional ecosystem.

The timing matters. The Negro National League formed in the shadow of World War I’s aftermath and the racist violence and backlash that surged during and after the war years. In that environment, building Black institutions was not a retreat from American life; it was an attempt to survive it with dignity intact. Gerald Early, quoted in The Atlantic, describes the impulse with blunt clarity: the brutality of the era convinced many Black Americans that they needed to “close ranks” by building their own institutions.

This is why the Negro National League cannot be reduced to an athletic milestone. It was a form of collective economic self-defense. It professionalized a labor market for Black ballplayers. It created predictable revenue streams for Black-owned franchises. It provided a stage on which Black communities could experience joy and virtuosity in public—an experience that was not trivial in a society that policed Black happiness as aggressively as it policed Black movement.

When people say the league “mattered,” they often mean it symbolized excellence under constraint. That is true, but incomplete. The league mattered because it did what segregation tried to prevent: it turned Black excellence into repeatable systems—schedules, contracts, travel arrangements, media coverage—rather than isolated miracles.

The business: Gate receipts, logistics, and the invention of Black sporting modernity

To understand how the Negro National League worked, you have to think like a promoter and a logistician, not just like a fan. In white baseball, stability was reinforced by a network of established stadiums, municipal relationships, and mainstream press coverage. In Black baseball, stability had to be manufactured—often city by city, weekend by weekend.

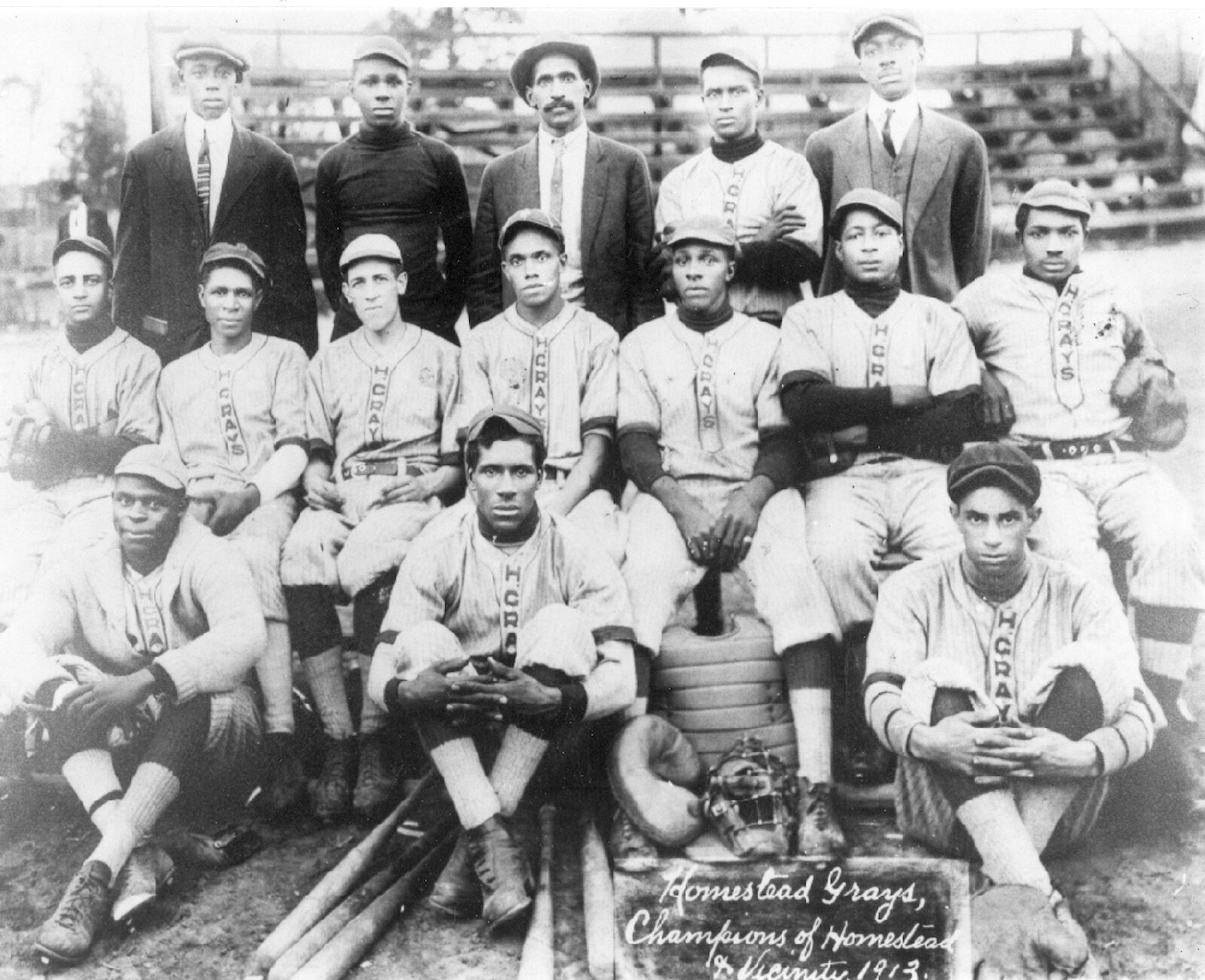

Major League Baseball’s own historical overview notes that Foster’s Chicago American Giants drew enormous crowds in the early years, citing nearly 200,000 spectators for the club during the 1921 season as an example of what organized Black baseball could generate when properly marketed and scheduled.

Crowds were the visible metric. The less visible work was the constant negotiation required to secure fields, schedule opponents, and ensure teams could travel safely through regions where Black travelers faced harassment, denial of service, and violence. A league structure helped because it formalized relationships among owners and made the product more legible to fans. It’s easier to commit to a team when the season feels like a season—when standings mean something, when rivalries recur, when a pennant chase can be followed through the Black press.

That press mattered. Foster himself wrote in the Chicago Defender, urging Black baseball executives not to surrender control to white interests and arguing for a unified league. The Atlantic recounts this as part of the lead-up to the 1920 meeting, framing Foster’s writings as both warning and blueprint.

In other words: the Negro National League was not simply founded in a meeting. It was incubated in public argument—editorials, debates among owners, and a growing realization that talent without infrastructure could be exploited.

The cultural center: Why the league was also a civic institution

One of the most quietly revealing details in The Atlantic’s account is not about a player at all, but about time. The essay describes a fan culture so intense that churches moved service times up so congregants could make it to games. That is not merely a charming anecdote. It is a measure of centrality. It suggests that league games functioned as a kind of weekly civic ritual: a gathering where Black communities could see themselves as a public, not only as individuals navigating private survival.

In many towns, especially those shaped by industrial migration and the Great Migration’s reshaping of Northern and Midwestern cities, Negro National League games offered something rare: a mass event controlled by Black people, for Black people, featuring Black excellence as the main attraction. The league, therefore, doubled as a cultural commons. It brought together laborers and professionals, churchgoers and night-shift workers, children and elders. It sold concessions and sold meaning. It helped sustain the kind of urban Black public life that historians often describe through music scenes and newspapers—jazz districts, editorial offices, fraternal organizations—except here the language was fastballs and double plays.

Kansas City’s Negro Leagues Baseball Museum emphasizes this geographic and cultural continuity, noting that it operates only blocks from the Paseo YMCA where the league was established, situating the founding within a broader Black cultural corridor.

That proximity is more than tourism trivia. It’s a reminder that Black baseball’s story is inseparable from Black urban geography: neighborhoods built under constraint becoming engines of creativity and commerce anyway.

The on-field product: Innovation, performance, and the refusal of inferiority

The Negro National League’s significance also rests on baseball itself—on the style of play, the strategies, and the personalities that shaped the sport’s evolution. Even when mainstream institutions refused to recognize Black baseball as “major,” the innovation was already happening, influencing how the game looked and felt.

The Atlantic essay, in discussing The League, emphasizes how Negro Leagues players pioneered a dynamic style that helped define contemporary baseball, and it underscores the contradiction at the center of the sport’s mythology: the modern game absorbed Black creativity while denying Black players equal access to its most visible stage.

The Baseball Hall of Fame likewise frames the creation of the Negro Leagues as proof of equivalency—Black players could compete “on even terms” with white counterparts and draw comparable interest from fans.

These statements matter because for decades, segregation’s defenders used “quality” as a fig leaf. The Negro National League stripped that argument of plausibility by staging a product too entertaining, too competitive, and too popular to dismiss.

The league and the record: Why “official” recognition arrived late—and why it still matters

For much of the 20th century, Black baseball’s greatest insult was not only exclusion from the majors but exclusion from the official archive. A league can exist in reality and still be treated as rumor if the record books refuse to count it.

In December 2020, Major League Baseball announced it would confer “major league” status on seven Negro Leagues that operated between 1920 and 1948—framing the move as a correction of a “longtime oversight.” The announcement was symbolic, but it was also procedural: it set in motion the work of integrating Negro Leagues statistics into MLB’s historical record.

That integration became tangible in May 2024, when MLB announced that Negro Leagues statistics had officially entered the major league record, following an expert review process. MLB noted that available records for the 1920–1948 period are estimated to be roughly three-quarters complete, and that ongoing research—particularly by projects such as the Seamheads Negro Leagues Database—could lead to future revisions.

When the numbers moved, the story moved with them. The Associated Press reported that Josh Gibson, long understood by Black baseball devotees as a mythic hitter, now appears atop MLB’s official career batting average list at .372, surpassing Ty Cobb’s .367, along with other leaderboard shifts in slugging and OPS.

To some fans and historians, this is a long-overdue public acknowledgment: the ledger catching up to the truth. To others, it is complicated—an institutional embrace arriving after decades of institutional neglect, raising questions about whether recognition without restitution can ever be enough. The Guardian captured that debate directly in 2024, describing the move as an essential correction while also documenting skepticism that it may be “too little, too late,” especially in a moment when Black representation in MLB remains low relative to the league’s demographics and history.

Ebony’s reporting also reflects the ambivalence, interrogating whether folding Negro Leagues statistics into MLB’s historical record is the best way to honor players who were excluded by design, and emphasizing that statistical inclusion cannot substitute for a full accounting of what segregation cost in money, health, and opportunity.

The point is not to litigate feelings. It is to recognize that archives are power. The Negro National League was founded, in part, because white baseball’s power could not be persuaded into fairness. When MLB now updates its archive, it is engaging in a form of retroactive governance: deciding what counts as “major,” what counts as history, what counts as America.

What the league made possible: Wages, travel, fame, and a Black public sphere

One temptation, especially in celebratory narratives, is to treat the Negro National League as a beautiful workaround—an alternate route around the color line. But workarounds can become worlds. The league did not merely route around exclusion; it created an ecosystem that made Black fame and Black professionalism legible on their own terms.

Players were not just athletes; they were public figures whose excellence traveled ahead of them through newspapers, word of mouth, and the ritual repetition of rivalries. The league helped standardize that fame. It gave it seasonal rhythm.

Owners and executives were not only sportsmen; they were business operators who built enterprises under hostile conditions, managing risk in a segregated economy. The story of the Negro National League is therefore also a story about Black entrepreneurship: about using the tools available—real estate, contracts, touring schedules, promotion—to build a stable product.

And fans were not only consumers; they were co-authors of meaning. They made the games matter by showing up, by reorganizing their weeks around first pitch, by turning ballparks into civic theaters.

The hard truth inside the triumph: Integration as both breakthrough and extraction

A foundational tension runs through Black baseball history: the victory of integration was also, for Negro Leagues owners and many communities, a kind of extraction.

The Atlantic describes how The League documentary complicates the familiar triumph story of Jackie Robinson by foregrounding what was lost when the majors began signing Black stars without compensating the Black teams that developed them. White MLB owners, the essay notes, often did not pay Negro Leagues owners for the talent they “poached,” crushing the economic prospects of Black teams in the process.

In this framing, integration is not dismissed; it is contextualized. Breaking the color barrier was a milestone that mattered profoundly for civil rights and for the legitimacy of Black citizenship. But it also accelerated the decline of a Black-controlled sports economy—a league system that had provided jobs, visibility, and ownership opportunities.

This is one of the Negro National League’s enduring lessons: Black institutions are not only responses to exclusion; they are reservoirs of autonomy. When autonomy is surrendered—whether by force or by the seductive promise of inclusion—something more than the immediate barrier changes. Whole ecosystems can collapse.

The league as a template: Institution-building under pressure

If you zoom out from baseball, the Negro National League begins to resemble a pattern repeated across Black American history: when mainstream institutions deny access, Black communities build alternatives that become cultural engines. Historically Black colleges and universities, mutual aid societies, Black newspapers, Black churches, and Black fraternal organizations all share this basic structure—self-governance as survival, and survival as creativity.

In that sense, the league is part of the same lineage as any Black institution built to counter a hostile public order. The league was not founded because its creators preferred separation. It was founded because exclusion left them no alternative if they wanted dignity, employment, and an arena to demonstrate excellence.

That institutional lesson echoes far beyond sport. It also connects—philosophically, not directly—to the question of how America documents, forgets, and later tries to “correct” its own story. In your attached Tulsa Race Massacre commission-related material, the central moral argument is that truth-telling and remedy cannot be separated: that a nation must identify what happened, who benefited, and what repair requires.

The Negro National League’s history poses a parallel question. If MLB’s record books are updated, what else should change? If the archive admits what it denied, what obligations follow?

The modern afterlife: Museums, documentaries, and the ongoing fight over narrative control

It is not accidental that the Negro Leagues Baseball Museum has become a central node in the league’s modern afterlife. Museums do not only preserve artifacts; they adjudicate meaning. The NLBM situates itself geographically close to the league’s founding site and frames Negro Leagues baseball as the highest level of professional baseball played among African Americans during a defined era, emphasizing both the sport’s richness and the need to tell this history with precision.

The past few years have also produced a wave of renewed popular attention: Sam Pollard’s documentary The League, discussed in The Atlantic and in The Guardian, offers a narrative that treats Negro Leagues history not as a sentimental prelude to integration but as a major chapter of American institutional life, with its own heroes, villains, internal debates, and unfinished reckonings.

The renewed attention has had practical effects. Media coverage has followed museum expansion efforts and campaigns to preserve sites and artifacts. Associated Press reporting has highlighted the museum’s push to expand and the growing interest driven, in part, by mainstream baseball’s incorporation of Negro Leagues history into products and official records.

This attention is not purely benevolent. Every surge of interest in Black history carries the risk of simplification—turning complex stories into inspirational wallpaper. The more useful approach is the one modeled by the best of the recent writing: insist on the league’s greatness without sanitizing the conditions that made it necessary.

The founding’s significance, stated plainly

The Negro National League was significant because it transformed a scattered field of teams into a system that could survive. It proved that Black baseball was not a novelty circuit but a professional enterprise with standards and ambition. It created a Black-run economy in a segregated sports landscape. It anchored civic rituals that organized community life. It produced innovations that shaped the modern game. It generated public memory and, eventually, forced the broader baseball establishment to confront its own historical distortions.

It was, in short, a declarative that Black players could play. But that Black executives could govern. That Black communities could sustain major entertainment industries. That Black audiences constituted a national market with tastes and loyalties sophisticated enough to support a league.

And it was a declaration made in a specific place—Kansas City’s Paseo YMCA—by men who understood that waiting for recognition was another form of losing.

What remains unresolved

A longform account of the Negro National League’s founding cannot end with a ribbon-cutting, because the league’s story was never only about beginnings. It is also about what came after: the extraction of talent, the collapse of Black-owned franchises, and a national memory that treated Black baseball as a side chapter until activism, scholarship, museums, and community insistence made that erasure harder to maintain.

The recent integration of Negro Leagues statistics into MLB’s official record is meaningful precisely because it demonstrates that “official” history is not neutral—it is curated. MLB’s own statement about record completeness and ongoing revisions is an admission that the archive is still under construction.

But archives, even corrected ones, cannot replace what was taken: the ownership opportunities foreclosed, the intergenerational wealth denied, the civic institutions weakened, the careers shortened by stress and discrimination, the legends who died without seeing their names treated as equal in the very sport they helped invent.

That is the enduring significance of the Negro National League: it forces a double vision. You can admire the beauty of what was built, and still tell the truth about why it had to be built at all.

More great stories

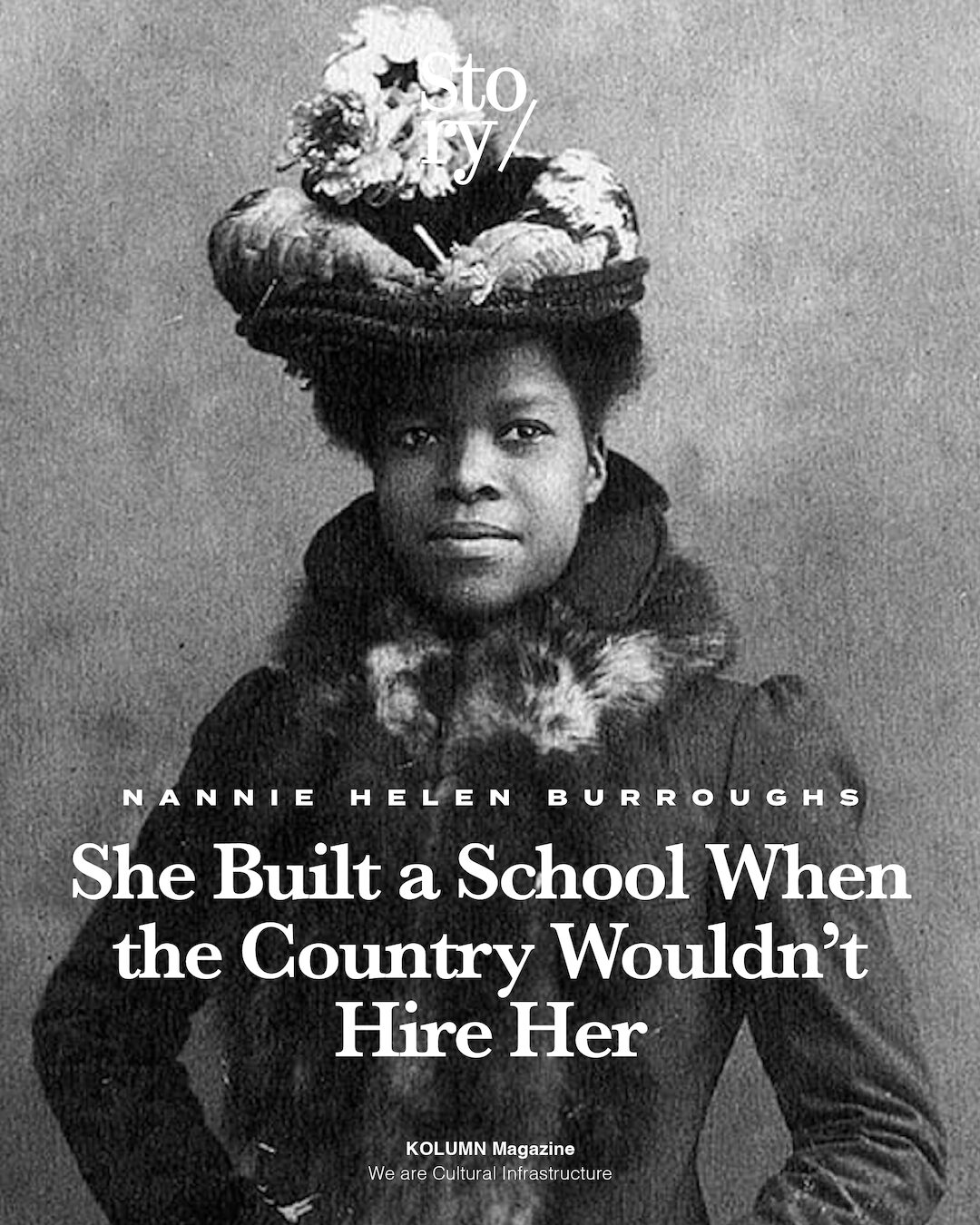

She Built a School When the Country Wouldn’t Hire Her