The New York Renaissance didn’t ask to be remembered as symbolic. They built a business, perfected a game, and took championships when championships were finally put in front of them. If their story still feels like a secret, that is less a reflection of their footprint than of the nation’s habits of attention.

The New York Renaissance didn’t ask to be remembered as symbolic. They built a business, perfected a game, and took championships when championships were finally put in front of them. If their story still feels like a secret, that is less a reflection of their footprint than of the nation’s habits of attention.

By KOLUMN Magazine

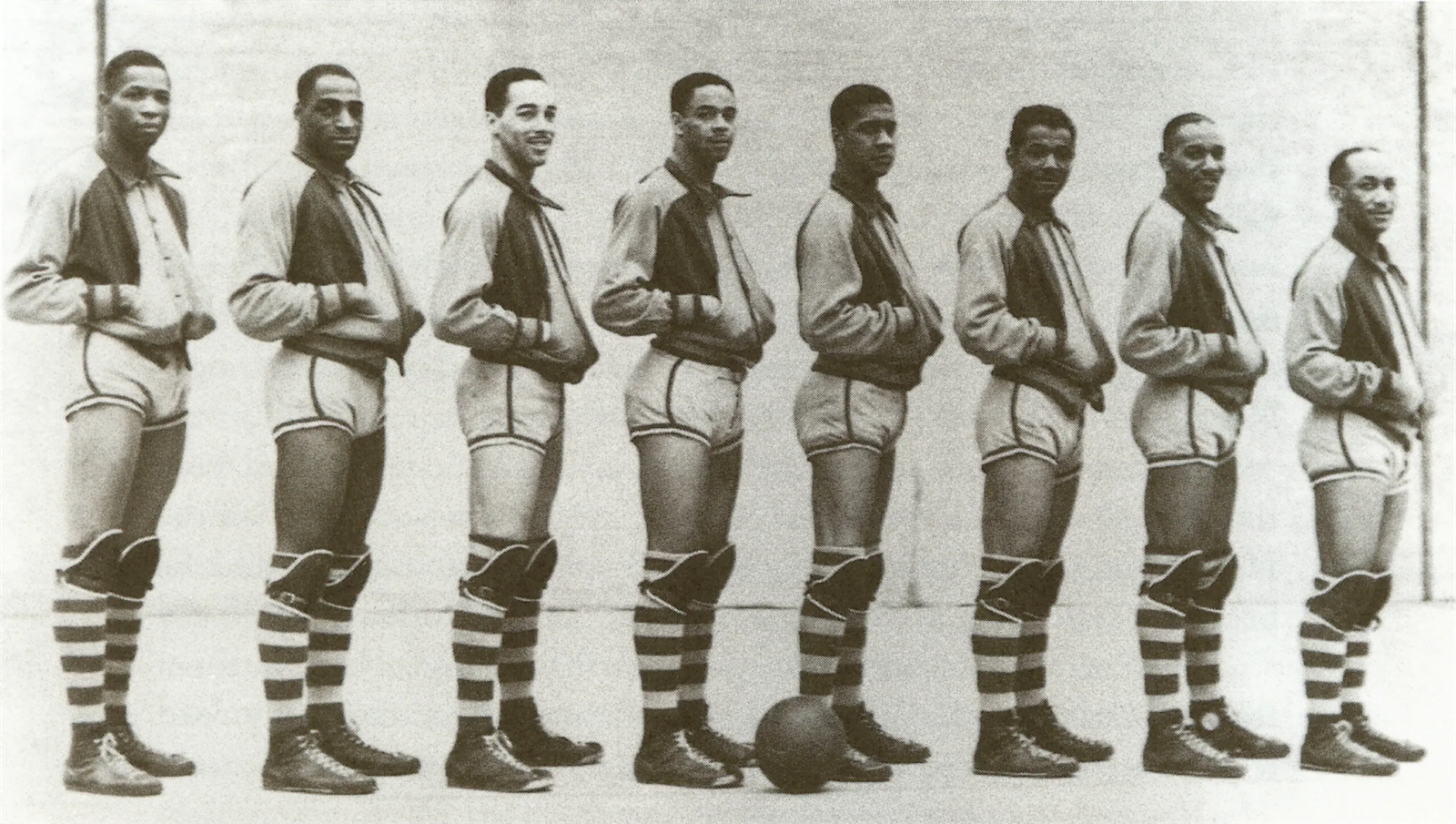

The most revealing way to understand the New York Renaissance is to picture a place, not a box score.

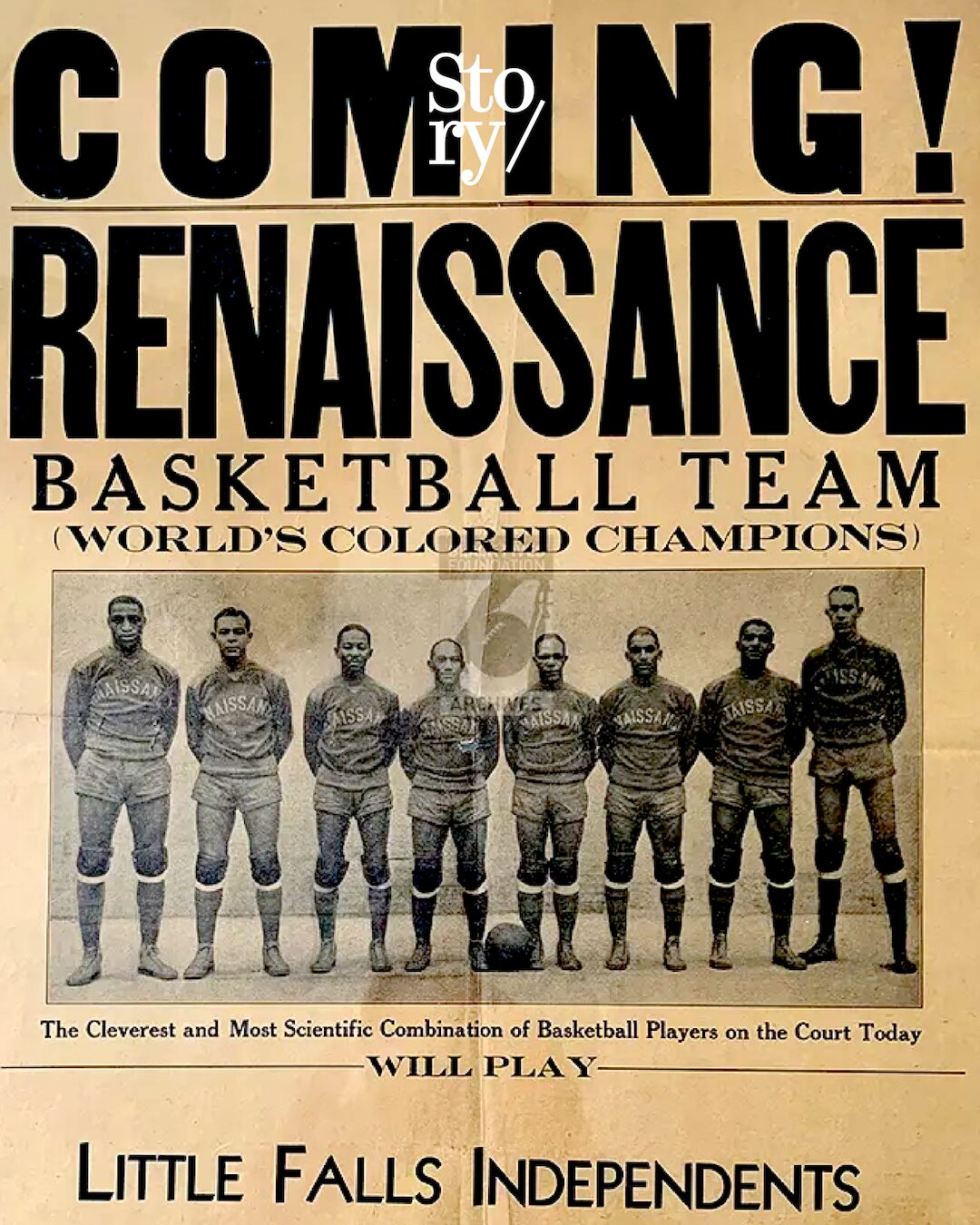

Harlem in the 1920s was performing itself into a new kind of visibility. Art and argument spilled from rent parties and editorial pages; jazz and politics moved through the same rooms. On Seventh Avenue, near 138th Street, a glittering entertainment complex—the Renaissance Casino and Ballroom—offered music, social life, and an aspirational sheen. And there, on a floor designed for dancing, a man named Robert “Bob” Douglas engineered a sports institution.

The arrangement that launched the Rens was both practical and visionary. Douglas, a savvy basketball organizer in a segregated market, made a deal with the Renaissance’s owner that tied team identity to venue promotion: the club would adopt the “New York Renaissance” name, and in return it would gain a stable home court. The branding was not incidental. Harlem already understood what the rest of the country was learning: a name could be a stage.

Rens games were, from the start, more than games. The team played in the same complex where nightlife pulsed; contests were often followed by dances, and the environment made basketball feel less like an amateur gym pastime and more like a ticketed cultural event. That blend—sport as entertainment, sport as social gathering, sport as business—reads now like a blueprint. But in 1923, it was also a workaround for exclusion: if the mainstream infrastructure would not host a Black professional team on equal terms, Douglas would build an ecosystem where he could.

This is where the Negro Leagues analogy sharpens. As with Black baseball owners who created parallel circuits when Major League doors stayed locked, Douglas didn’t just field talent; he built a platform. He introduced contracts to keep his roster intact, professionalizing labor and stabilizing quality. In doing so, the Rens helped shift Black basketball’s center of gravity away from purely amateur clubs toward professional competition—an economic and cultural transition with long consequences.

Bob Douglas and the business of refusing diminishment

Douglas is often described as the “Father of Black Professional Basketball,” and the phrase is not just ceremonial. Born in St. Kitts and based in New York, he became a promoter, manager, coach, and—crucially—owner, at a time when ownership was the surest defense against exploitation.

In the version of American sports history that gets repeated most easily, professional basketball begins in small regional leagues and eventually becomes the NBA. The Rens sit awkwardly in that narrative because they were both central and sidelined: central in quality, innovation, and popularity; sidelined by the country’s refusal to treat Black excellence as fully legitimate. Douglas’s accomplishment was to build a team so good—and so relentlessly scheduled—that ignoring it became an act of will.

He coached and operated the Rens for decades, through eras when pro basketball itself was still unstable and disorganized. The club’s longevity—stretching into the late 1940s—was not guaranteed by institutional backing; it was earned through constant motion, constant negotiation, and an unglamorous fluency in the economics of the road.

A key detail, often missed, is that the Rens did not begin as a national touring machine. Early on, they played mostly in Harlem, benefiting from local audiences and the novelty of top-tier basketball staged amid a nightlife economy. But Harlem alone could not finance a full professional calendar forever. As attendance patterns changed, Douglas recognized what Negro Leagues owners and barnstorming baseball teams already knew: profitability often lived outside home. The Rens increasingly chased larger crowds and better guarantees by traveling—sometimes endlessly—across the country.

That barnstorming model was both a business strategy and a racial ordeal. The team could be invited onto white courts, but not into white hotels. They could fill arenas, but still be forced to hunt for meals and lodging under Jim Crow rules—especially on Midwest and national tours. The contradiction—your labor is desired, your humanity negotiable—was the atmosphere the Rens breathed.

Basketball, Harlem, and the aesthetics of speed

The Rens weren’t celebrated only for being first. They were celebrated because they were beautiful.

Contemporary descriptions and later scholarship emphasize the team’s passing, pace, and improvisational intelligence. The Naismith Hall of Fame’s own framing of the Rens highlights their “wizardry,” deception, and fast break as defining traits. If you’re looking for an argument that the Rens helped invent the modern spectator game, start there: quick ball movement, coordinated transition, and a style that felt like jazz in athletic form.

That jazz comparison is not a marketing flourish applied afterward; it’s embedded in how the Rens’ story has been told and curated, notably in the 2011 documentary On the Shoulders of Giants, written by Kareem Abdul-Jabbar and Anna Waterhouse and directed by Deborah Morales. The film positions the Rens’ style alongside the era’s cultural energy—Harlem’s assertion of Black modernity through art, sound, and public presence.

There is also a tactical reality underneath the poetry. Teams that travel constantly learn to win in hostile environments. They learn to quiet crowds, manage officiating that may not be neutral, and conserve energy in brutal schedules. The Rens played a staggering number of games across their existence—thousands, by many accounts and contemporary retrospectives—an output that reframes what “season” even means. The grind is part of the greatness.

And because professional basketball’s early structure was fragmented—loose leagues, independent clubs, invitations, tournaments—the argument over who was “champion” was often rhetorical. It depended on who would schedule whom, which promoters controlled which buildings, and which audiences could be reached. In that world, the Rens adopted a simple logic: play everybody.

Interracial basketball as both spectacle and stress test

One of the most historically significant aspects of the Rens’ rise is that interracial games were not a late development; they were a feature from early in the team’s life. The Rens’ first game is widely cited as a win against an all-white team, and early schedules leaned into the draw of interracial competition because it attracted crowds—including white spectators—who treated the contest as a referendum.

This created a strange dynamic: racism could be both the reason the game was staged and the reason the Rens’ excellence was doubted. Interracial matchups were marketed as novelty and conflict, but for the Rens they were also professional necessity and professional aspiration. Douglas wanted the most respected opponents because legitimacy was hard currency. To beat elite white teams was to claim a title the country refused to print.

No opponent symbolized that legitimacy chase more than the Original Celtics, a dominant white powerhouse of the era. The Rens pursued them repeatedly, and when the Rens finally beat them in 1925, it registered as a seismic Harlem moment—a local triumph with national implication.

The important point isn’t only that the Rens could win. It’s that they kept seeking the matchups that made denial harder. A segregated system can survive isolated exceptions; it struggles when excellence becomes routine.

The streak: 88 straight wins and a record that still taunts history

Every sports story has a number that becomes a mythic shorthand. For the Rens, it’s 88.

During the 1932–33 season, the Rens produced an 88-game winning streak—an achievement so extreme it still sounds like exaggeration in a modern professional context. The Basketball Hall of Fame recounts the streak as a defining accomplishment, and it is a major reason the 1932–33 Rens were enshrined collectively.

To understand the streak’s meaning, you have to hold two truths at once.

First, the Rens were genuinely dominant. Their roster was stocked with elite Black talent, stabilized through Douglas’s contract approach, and sharpened by constant high-level competition. Second, the environment they played in makes dominance harder, not easier. They did not enjoy the standard advantages of a settled league powerhouse: consistent travel conditions, predictable scheduling, neutral lodging, or a governing body invested in their mythmaking.

That tension is what turns 88 into more than trivia. The streak is an athletic fact, but it also functions as evidence against a cultural lie. In a segregated sports economy, Black teams were often framed as entertaining, talented, even dazzling—yet somehow not “official.” The Rens’ sustained winning made that distinction increasingly absurd.

The Hall of Fame’s decision to enshrine the team underscores an institutional recognition that came late but mattered: the Rens weren’t a side story; they were part of the main story of basketball’s development.

1939: When the Rens won a “world” title the country had to acknowledge

If the streak proved the Rens’ supremacy across a long stretch, the year 1939 provided something else: an integrated championship stage.

The World Professional Basketball Tournament—invitation-only, held in Chicago—created a rare bracket where Black and white teams competed for a national professional title. For a Black powerhouse like the Rens, it was the kind of opportunity Douglas had been chasing for years: not merely an exhibition, not merely a lucrative date, but a formal contest that could end in a trophy that carried public authority.

The Rens won.

Their path, as preserved in tournament accounts and historical summaries, required beating formidable opposition, including the Harlem Globetrotters en route to the championship game. In the final, the Rens defeated the Oshkosh All-Stars, an all-white team, 34–25—an outcome that landed as both sports result and social punctuation.

Individual honors also mattered. Clarence “Puggy” Bell was named the tournament’s Most Valuable Player, and Rens players appeared on all-tournament selections. In a segregated era, those recognitions were not just personal—they were part of the argument that Black teams were not merely capable of competing, but capable of defining excellence.

The Root, in a retrospective that reads like a corrective to mainstream forgetting, frames the 1939 championship as a key overlooked chapter of American sports history and points to the Rens’ extraordinary long-run record as proof of their stature. That impulse—correction—shows up repeatedly in Rens coverage. It’s a sign of how systematically their story was minimized.

The Globetrotters, the Rens, and the fork in basketball’s road

Because the Harlem Globetrotters became an enduring global brand, they often stand as the default reference point for early Black professional basketball. The Rens complicate that because they were not built as a comedy exhibition; they were built as a championship operation.

That distinction is sometimes overstated—the Globetrotters could play, and did win major competitions, including the World Professional Basketball Tournament in 1940. But the Rens’ identity was different in tone and intent. They played in a Harlem ballroom with dances afterward, yes—but their core pitch was sporting supremacy. Their rivalry and overlap with the Globetrotters, especially in tournament contexts, illustrates a broader question Black teams faced: in a country that monetizes Black performance but restricts Black authority, do you survive by leaning into entertainment value or by insisting on competitive legitimacy? Many did both. The Rens tried to make legitimacy unavoidable.

The Guardian, in a broader piece about the NBA and “world championships,” briefly notes the Rens as a Black-owned, all-Black team in the integrated tournament context and emphasizes the discrimination they faced on tour. Even as a passing reference, it captures the central contradiction: the Rens were good enough to be in the room, but not always treated as full members of the sport’s imagined nation.

Life on the road: Segregation as logistics, not just ideology

Sportswriting often treats racism as a moral atmosphere—hatred in the stands, slurs on the court. For the Rens, racism was also scheduling, lodging, transportation, and food.

Barnstorming meant constant travel, frequently through regions where Black travelers could not rely on basic services. This is where the Rens’ story aligns closely with Negro Leagues history. Long before the civil rights era’s headline victories, Black teams lived the daily compromises of “where can we sleep tonight” and “who will serve us.” The cost wasn’t only dignity. It was rest, health, performance, and safety.

And yet, the road also produced a strange kind of integration-by-necessity in the sport itself. Teams that play each other constantly begin to recognize one another’s excellence even when society pretends otherwise. On the Shoulders of Giants frames this as part of the Rens’ long arc: opponents could become peers even when the country remained segregated.

The Rens were, in effect, conducting an experiment: what happens if you make interracial competition routine? You force skill to speak in a language that prejudice has to work hard to mistranslate.

A missing chapter in the NBA origin story

By the late 1940s, professional basketball was consolidating. The National Basketball League (NBL) and the Basketball Association of America (BAA) were the most prominent white-led pro structures, and their eventual merger would create the NBA.

The Rens did not glide smoothly into this new order. In 1948–49, they relocated and played as the Dayton Rens, filling a vacancy created when another team folded; after the season, they disbanded amid the merger that formed the NBA’s 1949–50 season. The symbolism is hard to miss: as the modern league structure hardened, the all-Black independent powerhouse that had proven itself for decades did not become a foundational franchise. The new league would initially remain all-white.

That exclusion is not merely a sad footnote. It shaped which stories became “league history.” Institutions memorialize their own ancestry. When the Rens were kept outside the NBA’s founding mythology, their innovations and achievements became easier to misplace.

This is why later recognition—Hall of Fame enshrinement, documentaries, Black press remembrance—matters beyond ceremony. It is a struggle over what counts as professional sports history.

Recognition, belated and necessary

The Rens have been honored in ways that confirm their stature even if those honors arrived long after their prime.

The Naismith Memorial Basketball Hall of Fame includes the New York Renaissance as an enshrined team, foregrounding both their style and their achievements, including the 88-game streak and their role as an early dynasty. The Hall of Fame narrative is itself telling: it emphasizes passing brilliance and barnstorming dominance, describing the Rens as a team that could render opposition helpless. In other words, it frames them not as a social milestone with a basketball hobby attached, but as basketball innovators with social consequences.

Bob Douglas, too, was inducted as a contributor, reinforcing the idea that his primary impact was structural: building Black professional basketball as an enterprise.

Then there is the cultural afterlife: On the Shoulders of Giants functions as both documentary and indictment—an argument that a team of this magnitude should not have been relegated to niche memory. Abdul-Jabbar’s involvement is significant. As a figure who lived inside the NBA’s modern celebrity machinery, he used that platform to insist that the league’s prehistory included Black ownership, Black strategy, Black spectacle, and Black championship credibility. The film’s interview roster—spanning activists, scholars, and basketball royalty—signals that the Rens’ story is not simply sports nostalgia; it is a missing civic chapter.

In the Black press, the tone often carries a familiar frustration: why did we have to keep reminding the country? A 2014 New York Amsterdam News piece framed the Harlem Rens as perhaps the greatest of the Black Fives, situating them in a lineage of Black athletic achievement that predates mainstream inclusion. The Root’s remembrance does similar work, treating the 1939 title as a moment that should live in the same mental space as other barrier-breaking sports milestones.

The Rens as cultural infrastructure: Harlem’s entrepreneurship in uniform

If you’re editing this story for a magazine—if you’re trying to make it feel like more than a sports feature—the richest angle may be that the Rens were a form of cultural infrastructure.

They were a Black-owned franchise attached to a Harlem entertainment venue, selling nights out that combined sport and music, building local ritual, circulating money through a community ecosystem that segregation tried to starve. The Renaissance Ballroom itself continued as a Harlem hotspot for decades, and Douglas remained connected to its management after the team’s demise, a reminder that the Rens were never just a traveling team—they were part of a neighborhood’s business and social identity.

This is where the “Renaissance” name becomes more than venue promotion. The Harlem Renaissance is often narrated through writers, painters, musicians, and political thinkers. The Rens suggest an adjacent thesis: athletic performance, too, was a form of modern Black expression, and it operated with its own aesthetics—speed, improvisation, collective intelligence—mirroring the era’s cultural innovations.

Sports historians and local Harlem history projects have documented how basketball fit into 1920s Harlem life, including the significance of marquee wins like the 1925 victory over the Original Celtics. When thousands showed up, they weren’t only witnessing points. They were witnessing proof.

Why the Rens still matter now

It’s tempting to treat the Rens as an inspirational prologue: brave men, hard times, eventual progress. But that framing can soften what the story actually demands we confront.

The Rens matter because they expose how American professional sports narratives are curated—how “firsts” are recognized selectively, how championships can be treated as unofficial when the winners are inconvenient, how ownership and institutional memory shape public history.

They also matter because they complicate the idea that integration automatically delivers justice. The Rens proved the product; they did not automatically receive the franchise rights. They demonstrated the audience; they did not automatically receive the league’s legitimacy. They built professional Black basketball; they did not automatically become part of the NBA’s founding architecture.

And they matter because their style looks like the sport we now call modern. When today’s basketball celebrates pace-and-space, passing angles, transition offense, and improvisational chemistry, it is echoing principles that teams like the Rens helped popularize under conditions far harsher than any modern road trip. The Hall of Fame’s language about their passing and fast break—about opponents rendered helpless—reads like a description of the game’s aesthetic ideal.

Finally, they matter because they remind us that Black sports history is not only a history of entry into white institutions. It is also a history of building independent institutions so strong that the country eventually had to negotiate with them.

The New York Renaissance didn’t ask to be remembered as symbolic. They built a business, perfected a game, and took championships when championships were finally put in front of them. If their story still feels like a secret, that is less a reflection of their footprint than of the nation’s habits of attention.

In the end, the Rens’ most enduring accomplishment may be this: they made it possible to imagine professional basketball as both artistry and industry—something you could sell in a ballroom and prove in a coliseum, something that could carry a community’s pride and a country’s contradictions at the same time.

More great stories

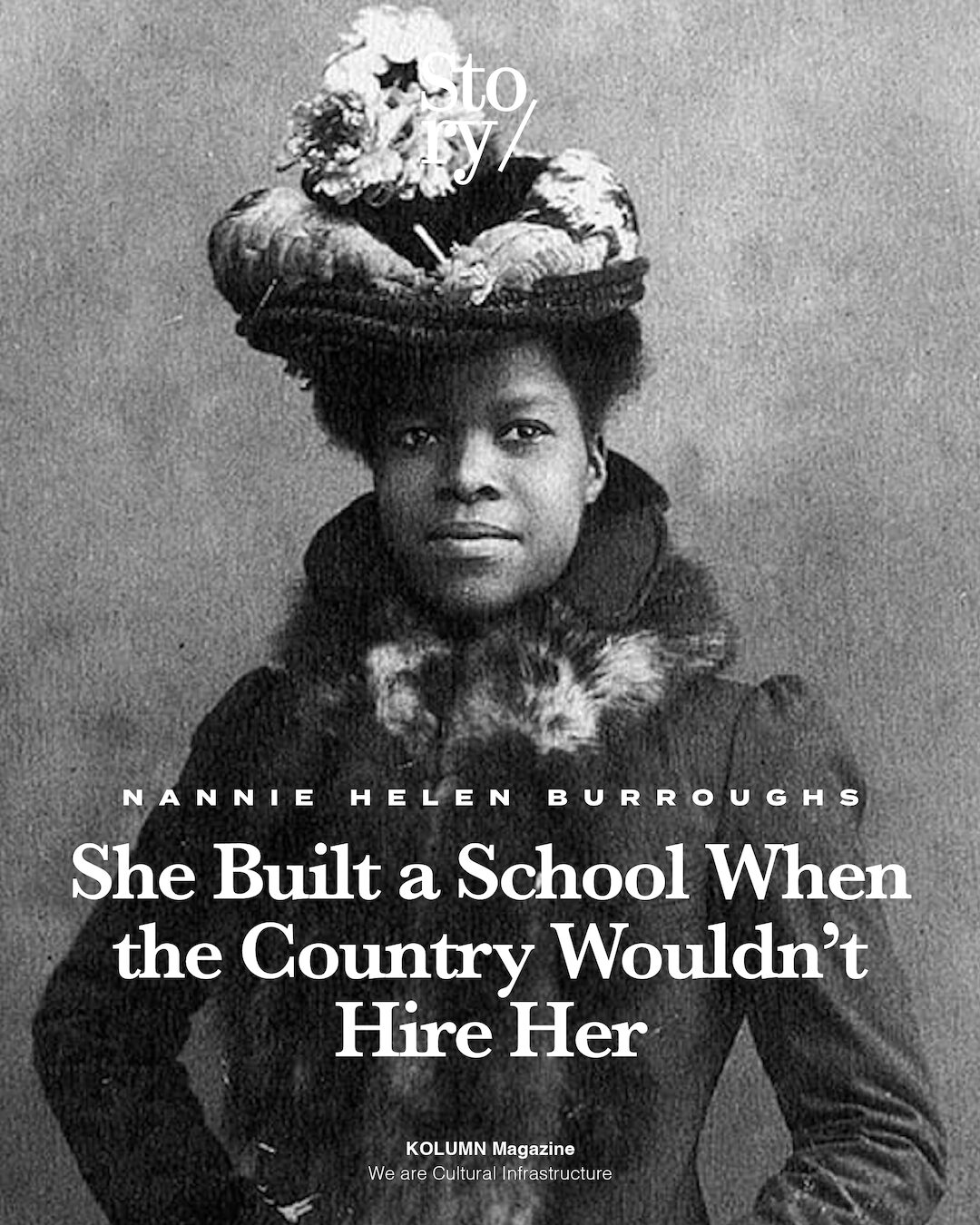

She Built a School When the Country Wouldn’t Hire Her