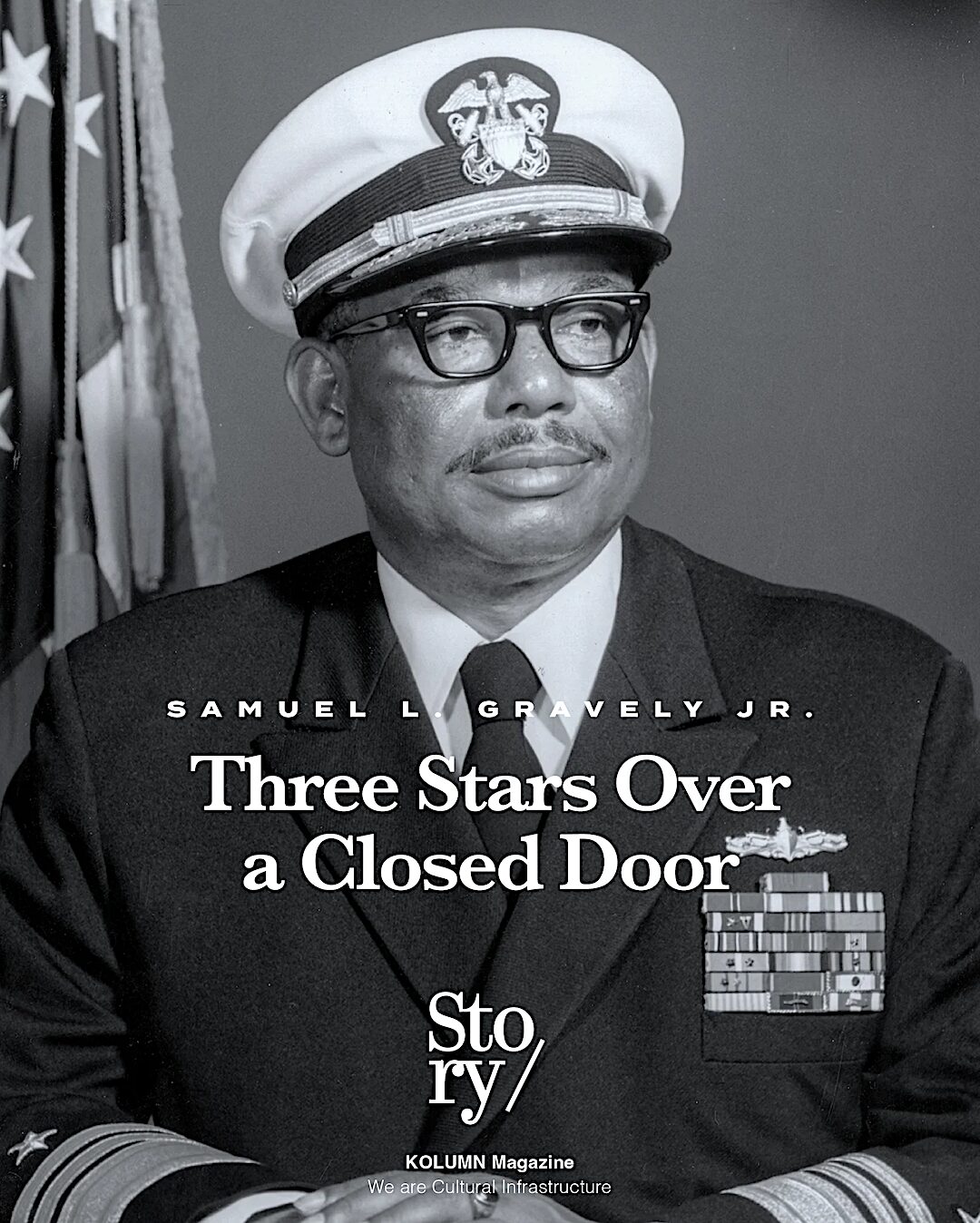

Her work sits at the crossroads of American abstraction, Black cultural life in Washington, and the politics of recognition: who gets admitted to the story of modern art, and when.

Her work sits at the crossroads of American abstraction, Black cultural life in Washington, and the politics of recognition: who gets admitted to the story of modern art, and when.

By KOLUMN Magazine

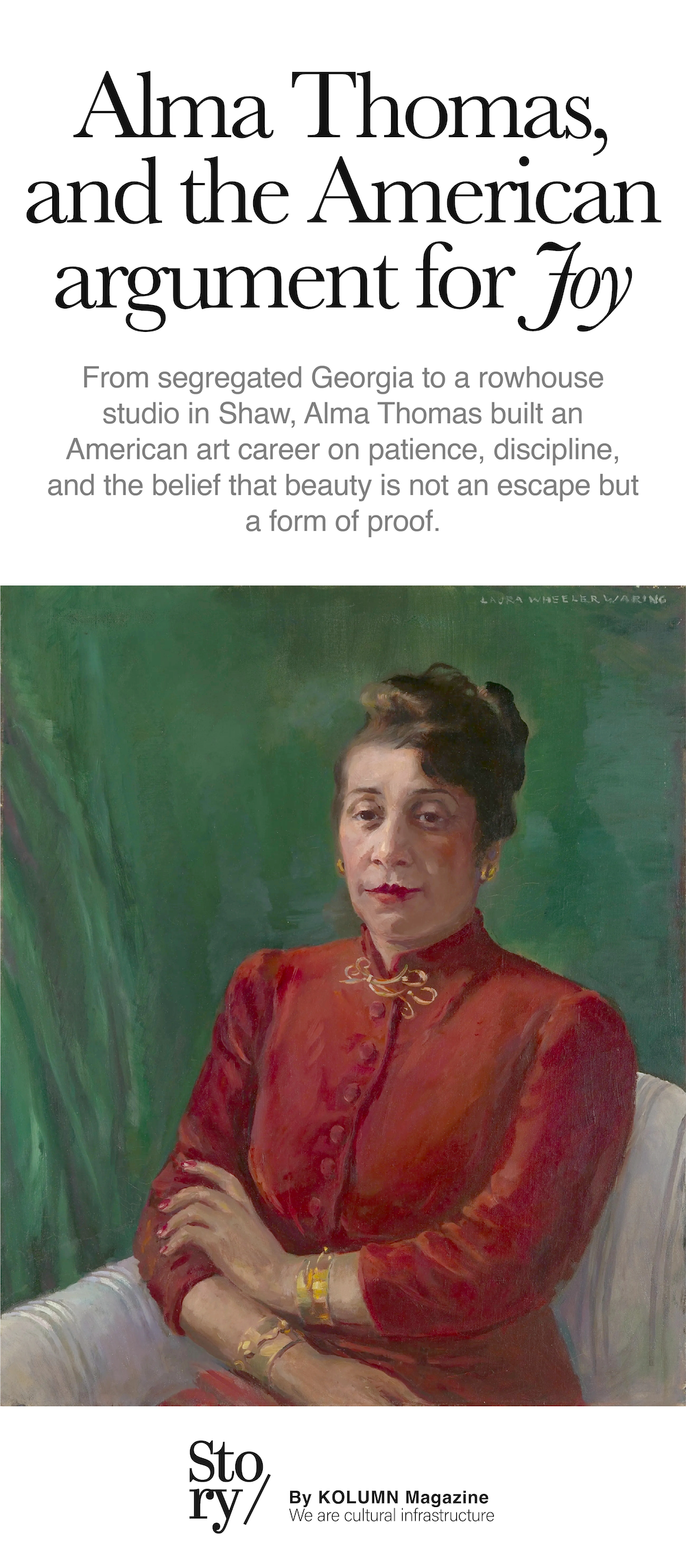

On a quiet street in Washington, D.C., not far from the city’s museums and a short walk from the institutions that trained generations of Black professionals, Alma Woodsey Thomas lived an unusually consistent life. She kept returning—home to the same neighborhood, day after day to classrooms filled with adolescents, year after year to galleries and openings, and, with increasing insistence, to a private problem that can look deceptively simple when it succeeds: how to make color carry feeling without telling a story.

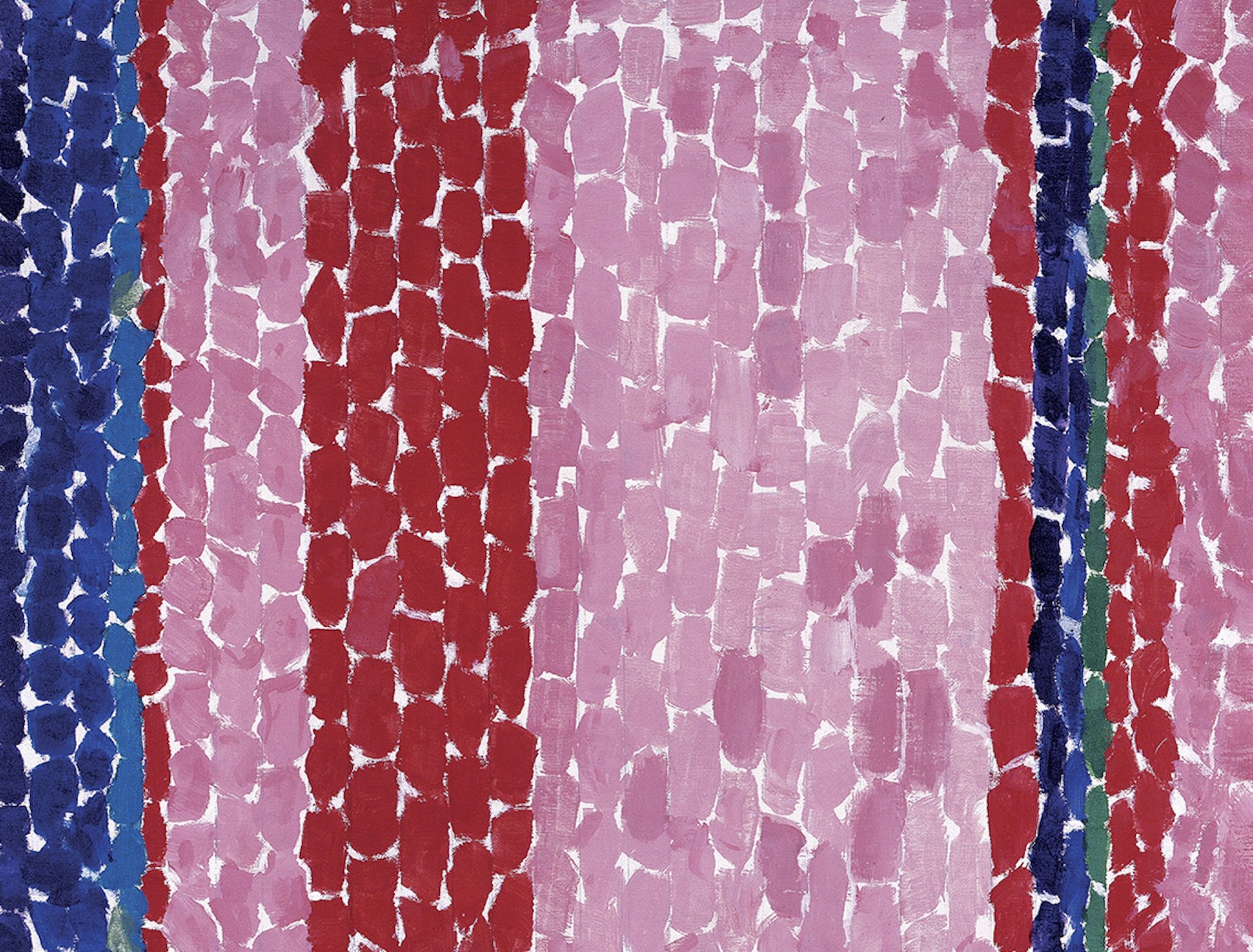

That problem, pursued for decades, eventually produced paintings that seem to speak in a language of pure radiance—bands of broken color, tessellated strokes like stained glass or mosaic, concentric rings that pulse outward, as if the canvas were emitting weather. They are works many viewers first encounter as happiness: bright, buoyant, even playful. Yet Thomas’s life reminds you that joy, in American history, is rarely a naïve condition; it is often a decision. Born in 1891 and raised in an era when the rights and safety of Black Americans were routinely contested, she matured during the Great Migration, worked through Jim Crow, and built an art career while the nation’s museums and markets remained structurally hostile to Black women artists. Still, Thomas refused to treat aesthetic pleasure as a minor key. From the mid-1960s through the end of her life, she painted as though light itself were a civic resource—something to be studied, husbanded, and shared.

The headline version of her story—“she became famous late”—is true enough to be tempting, but it can flatten what matters. Thomas did not wake up at seventy and accidentally become a modernist. She built the conditions for her late work over a lifetime: through training, relentless looking, formal experiments that predated her “breakthrough,” and a 35-year tenure as an educator in the D.C. public schools that shaped how she thought about art’s role in daily life.

To write about Alma Thomas responsibly is to resist the inspirational shortcut. Her significance isn’t simply that she succeeded late; it’s that she succeeded precisely because she never stopped practicing—never stopped learning how a painting can be structured, how an image can be felt, how abstraction can be both personal and public. Her work sits at the crossroads of American abstraction, Black cultural life in Washington, and the politics of recognition: who gets admitted to the story of modern art, and when.

From Columbus, Georgia, to Washington, D.C.: the making of a lifelong student

Thomas was born in Columbus, Georgia, in 1891, into a Black middle-class family that valued education and cultural attainment. In 1907, her family moved to Washington, D.C., a relocation that placed her in a city with stronger educational opportunities for Black students than the South could offer at the time, and in proximity to the institutions that would shape her adult life. The move was not merely geographic; it was strategic—an investment in a young woman’s intellectual future at a moment when Black mobility itself was a political act.

Washington offered Thomas a latticework of possibility: Howard University, the city’s Black professional class, and a community of teachers, librarians, and artists sustaining one another in a segregated nation. Her identity as a “Washington artist” was not incidental. It gave her access to a local art scene that, while not as dominant as New York, enabled experiments and networks that would later become essential—especially for artists who were shut out of mainstream art-world pipelines.

Thomas studied at Howard University and is widely noted as the first graduate of Howard’s fine arts program, finishing in 1924. She also earned teaching credentials through the District’s teacher-training institutions. The dual track—artist and educator—wasn’t a compromise so much as a professional reality for many Black artists of her generation, particularly women: teaching offered stability, community standing, and a platform from which art could be pursued with seriousness.

“Miss Thomas” at Shaw: Education as studio practice

If you want to understand Thomas’s mature work, start not with a museum wall but with a classroom. From 1924 to 1960, she taught art at Shaw Junior High School in Washington, D.C., becoming, for many families, a familiar civic figure—“Miss Thomas,” the educator who made art matter in a system that often treated Black children’s creative lives as expendable.

A Smithsonian Archives of American Art account emphasizes that Thomas deliberately incorporated African American history into her teaching—an important detail because it complicates the persistent myth that Thomas’s abstraction was detached from race or politics. Pedagogy can be a kind of authorship: it shapes the cultural literacy of a community. Thomas’s career in the schools placed her inside a lived Washington that included the civil-rights movement, shifting neighborhood life, and the evolving aspirations of Black middle-class families. That context did not dictate what she painted, but it formed the atmosphere in which her work developed.

Thomas also kept studying. She took courses at American University, where she encountered rigorous approaches to modern painting and design and began exploring abstraction more seriously. The Whitney Museum’s artist profile describes her as moving toward prominence as a color-field abstractionist after devoting herself full time to painting, but it also stresses the longer arc: the Howard education, the decades of teaching, the ongoing engagement with Washington’s arts community, and the incremental movement into abstraction well before her national breakthrough.

In other words: she was not absent from art until retirement. She was building, slowly, the vocabulary she would later speak fluently.

The myth of the “late start,” and what the paintings actually show

Art history loves a conversion narrative: the moment when the artist becomes the artist. Thomas’s story is often told through one such turning point—retirement from teaching, an attack of arthritis, and then a surge of painting that produced the works for which she is now best known. There is truth here, but the danger is that it makes her mature style look like an inexplicable miracle rather than the culmination of decades of training and experimentation.

A Washington Post review of a major Thomas exhibition at The Phillips Collection emphasizes precisely this corrective: the show included key paintings from the 1950s that demonstrate her work “tending toward abstraction” long before she retired, and it used archival materials to argue that Thomas’s artistic identity should be understood as continuous, with fewer dramatic breaks than the legend suggests.

Continuity matters because it reframes Thomas’s late career as strategic maturation rather than accidental emergence. Even the arthritis episode—often cast as a crisis that “forced” her into painting—fits a more nuanced reading: physical limitation can intensify artistic focus, but it rarely invents it. What it can do is clarify what must be pursued while time remains.

A Washington modernist: Color, pattern, and the discipline of exuberance

Thomas is frequently associated with the Washington Color School, a loose grouping of artists linked by their engagement with color-field abstraction in the postwar period. The label helps situate her in a local modernist lineage, but it can also obscure her singularity. Many Washington Color School painters were connected to academic institutions and a formalist discourse that prized optical effects, flatness, and chromatic intensity. Thomas absorbed parts of this language, yet her work rarely feels like a cold argument. It feels like someone trying to translate lived sensation—gardens, weather, music, the shifting “afterimage” of sunlight—into a durable visual structure.

Her signature technique—short, irregular, mosaic-like strokes arranged in bands or dense patterns—invites comparisons to textiles, to stained glass, to Byzantine mosaics, to pointillism. The National Museum of Women in the Arts notes these distinctive brushstrokes as “lozenge-shaped” marks that can read as spontaneous but are, in practice, carefully organized. Her mature paintings do not drift; they lock into rhythm.

That rhythm is central to her significance. Thomas made abstraction that behaves like music—repetition with variation, a steady pulse, a sense of movement across a surface without a literal narrative. And she did it with an emotional register that remains rare in the canon of postwar American abstraction, which can skew macho, monumental, and often adversarial. Thomas’s canvases argue differently: they persuade by delight.

Her own statements about art underscore this orientation. In a citation attributed to a 1972 New York Times feature, Thomas is quoted saying that art “could be anything… as long as it’s beautiful”—a line that can sound simplistic until you read it as an ethical position, not a decorative one. Beauty, in her framework, is not trivial; it is a criterion that sets a standard for how human beings should shape the world.

Nature as a formal engine: Gardens, atmosphere, and the sky as studio

Thomas’s mature paintings are “intimately connected to the natural world,” according to the Smithsonian American Art Museum, which holds the largest public collection of her work. That connection is not the nature of realism. It is the nature of attention: the way light breaks across leaves, the way colors shift in the sky, the way seasonal change can be described through chromatic mood rather than pictorial depiction.

Consider her recurring interest in celestial phenomena. Works such as The Eclipse (1970) translate a specific event—a solar eclipse—into bands and gradients of color that feel both optical and emotional, as if the painting were recording not the scientific fact but the human perception of it. A contemporary education-oriented essay that cites Thomas’s eclipse painting frames her practice as grounded in observation and in an educator’s habit of close looking: seeing the world carefully and then designing a way to communicate what you saw.

Nature, for Thomas, functioned as a generator of systems: pattern, variation, periodicity. This is one reason her work has become increasingly relevant in contemporary conversations about abstraction. Many younger artists—particularly those interested in Black abstraction and the politics of visibility—have returned to Thomas not only for her biography but for her method: she offers a way to be rigorously formal without being emotionally sterile.

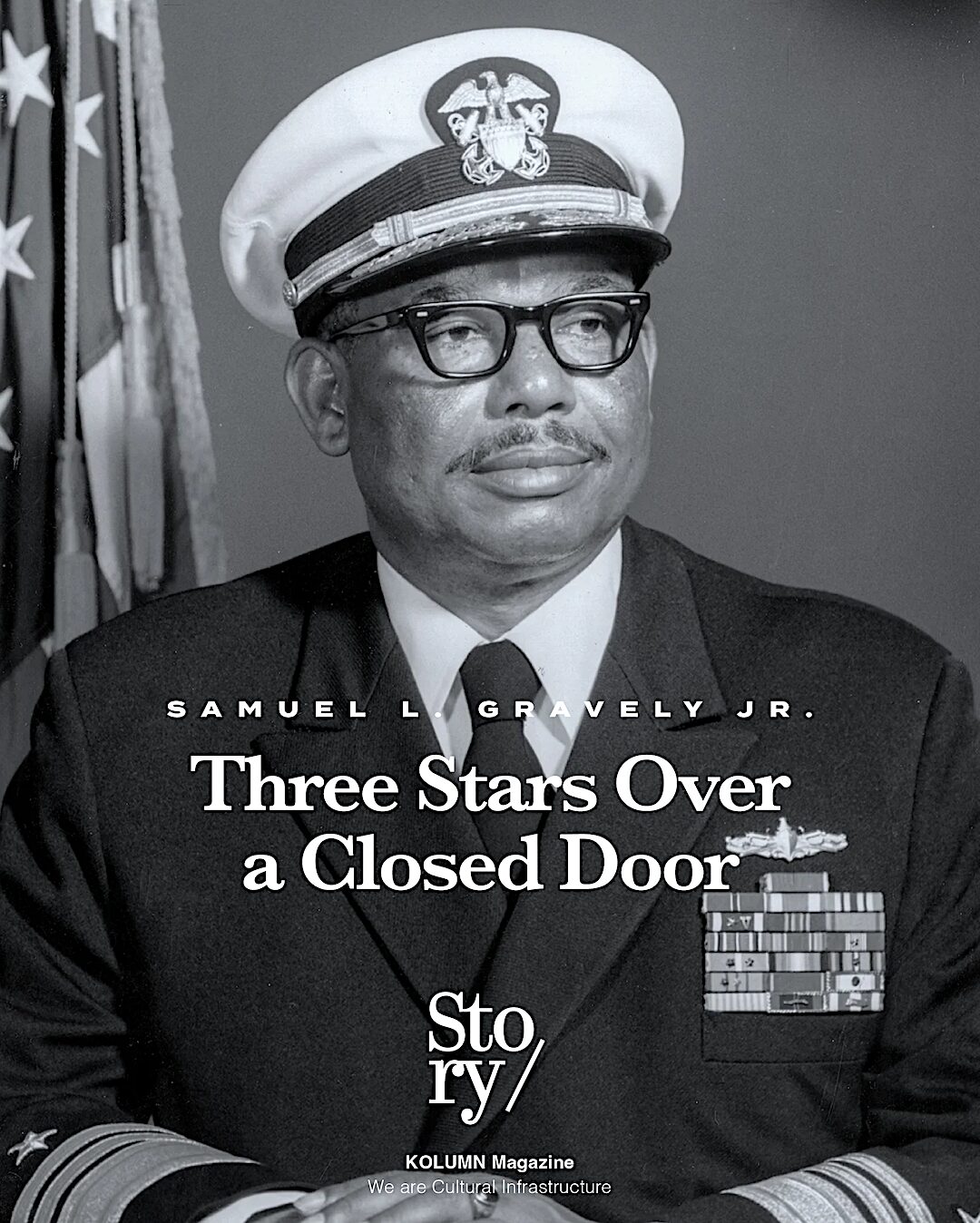

The Whitney moment—and what it meant to be seen

Thomas’s national breakthrough is often anchored to a specific institutional validation: her solo exhibition at the Whitney Museum of American Art in 1972, when she was in her late seventies. The Georgia Encyclopedia describes her as the first African American woman to have a solo exhibition at the Whitney—an institutional milestone that speaks less to sudden artistic arrival than to belated recognition by a major museum.

The Whitney show matters for two reasons. First, it formalized Thomas’s place in the narrative of American abstraction at a moment when that narrative was still being written largely without Black women. Second, it illustrates how museums operate as gatekeepers of art history: Thomas had been working for decades, but the imprimatur of a New York institution altered the scale of her reception.

Even in the way the story gets told—“At 77, she’s made it”—you can hear the art world’s surprise that a Black woman educator from Washington could produce work so confidently modern. Surprise, in such cases, is a confession: it reveals what the field assumed about who modernism belonged to.

Race, category, and the politics of interpretation

One of the most persistent tensions in writing about Alma Thomas is how to frame her relationship to Black identity and political life. There is a tendency, sometimes well-intentioned, to recruit her as an emblem of representation—proof that Black women were always present in modernism. There is also an opposing tendency to describe her work as “universal,” as if abstraction exempts an artist from the social conditions that shaped her opportunities.

Thomas complicates both camps. She did not typically make overtly political imagery in the manner of some contemporaries, and she expressed skepticism about being reduced to a racial category. Yet her life and work unfolded inside a segregated America; her teaching practice explicitly engaged Black history; and her success was constrained and delayed by the structures that marginalized Black women artists. Any account that treats her paintings as floating outside that reality misreads the ground they stand on.

The most honest approach is to accept the friction. Thomas could be an American modernist and a Black woman navigating exclusion. Her paintings could be formally ambitious and emotionally generous without serving as protest posters. In a country that often demands Black artists “explain” race for white audiences, Thomas’s insistence on beauty and color can itself be read as a refusal—a choice to claim the full range of artistic intention.

Resurrection and the White House: Symbolism, acquisition, and cultural memory

If the Whitney show represents institutional validation in the art world, Thomas’s entry into the White House collection represents a different kind of cultural inscription—one tied to national symbolism and public space.

In 2015, during Black History Month, Thomas’s painting Resurrection (1966) was unveiled as part of the White House Collection, with the White House Historical Association noting that she became the first African American woman to have her work added to that collection. The painting was placed in the Family Dining Room during the Obama administration.

This fact is frequently repeated because it carries obvious resonance: a Black woman’s abstraction—nonfigurative, unapologetically modern—hung in a building that has long functioned as a symbol of American power and exclusion. But the symbolism is not automatic; it depends on how you interpret what kind of inclusion this represents.

On one level, the acquisition is a corrective to omission: it acknowledges that the nation’s “official” spaces had failed to reflect the diversity of American cultural production. On another level, it risks becoming tokenistic if it is treated as an endpoint rather than a starting point. Thomas’s work entering the White House does not solve the structural inequities that delayed her recognition; it exposes them, by highlighting how long such a “first” took.

The White House Historical Association’s materials also clarify the acquisition process, noting collaboration with First Lady Michelle Obama. That detail matters because it places the painting within a broader Obama-era effort to diversify the White House’s visual culture—an attempt to make American iconography reflect a wider range of makers.

And yet the painting’s later movement between rooms across administrations also serves as a reminder: symbols can be repositioned, literally and figuratively, depending on who controls the space. Even when a work enters a collection, its visibility remains contingent.

The rowhouse studio: Discipline, community, and the life of a working artist

Thomas’s life was not that of an art-world celebrity. She lived for decades in the same family home in Washington, D.C., maintaining routines that sound less like myth than like work: teaching, painting, attending exhibitions, sustaining friendships. She was socially active in the city’s arts community and regularly went to openings—an important detail because it reminds us that she was not isolated. She was part of a network of Black Washington cultural life that included artists, educators, and intellectuals.

The artist’s papers, preserved through the Smithsonian’s Archives of American Art, provide a material record of this life—correspondence, documents, traces of the daily infrastructure that undergirds a career. Archives matter in Thomas’s story because Black women artists have so often been erased not only from exhibitions but from documentation. The survival and stewardship of her papers support the continued rewriting of art history with greater accuracy.

Her rowhouse becomes, in this context, more than a biographical detail. It is a symbol of persistence: art made at home, in the margins of institutional recognition, sustained by personal discipline and local community.

Why the work is still growing in stature

Thomas’s reputation has expanded significantly in recent decades. This growth is not only the result of market attention or institutional fashion, but of a broader re-examination of American modernism—a recognition that the “official” story was too narrow, too centered on a small set of mostly white, mostly male figures. Thomas benefits from this revision not because she is a convenient addition, but because her work withstands scrutiny. Once you see the paintings in person, the surfaces tell you what reproductions can’t: the physicality of the marks, the subtle shifts in hue, the sense that the image is assembled from decisions rather than poured out of spontaneity.

Her importance also lies in how her work speaks to contemporary aesthetic needs. In an era saturated with images engineered for outrage and speed, Thomas’s paintings demand a different tempo: they slow you down. They offer sensation without spectacle and complexity without aggression. That combination feels newly valuable.

Institutions have increasingly supported this reassessment. The Smithsonian American Art Museum foregrounds her as a major figure, with strong holdings that anchor scholarship and display. The National Museum of Women in the Arts situates her within a lineage of women who developed ambitious abstract languages despite structural obstacles. And major exhibitions—like the one reviewed in The Washington Post at The Phillips Collection—have used archival materials to reframe her “late bloom” as the visible crest of a lifelong practice.

Alma Thomas’s significance, distilled—without reducing her

To call Alma Thomas “inspiring” is not wrong, but it is insufficient. Inspiration can be a way of praising someone while keeping them at a safe distance. Thomas deserves closer reading than that.

She matters because she expands what American abstraction looks like and who it belongs to. She matters because she demonstrates that a life in teaching can be a life in art—not an alternate path, but a parallel one, with its own rigor and consequences. She matters because her work offers a model of formal invention that is neither hermetic nor didactic, neither trapped in autobiography nor emptied of it.

And she matters because her story exposes the lag between artistic achievement and institutional recognition—especially for Black women. When museums and publications “discover” Thomas in her seventies, the discovery says less about her than about them.

If Thomas’s paintings feel like light, it is because she treated light not as decoration but as a subject worthy of a lifetime. She studied it, structured it, broke it into tessellated marks, and reassembled it into something viewers can stand before and feel—something that looks like joy but is built from discipline.

That may be her most enduring lesson: beauty is not a temperament. It is a practice. (Smithsonian American Art Museum)

More great stories

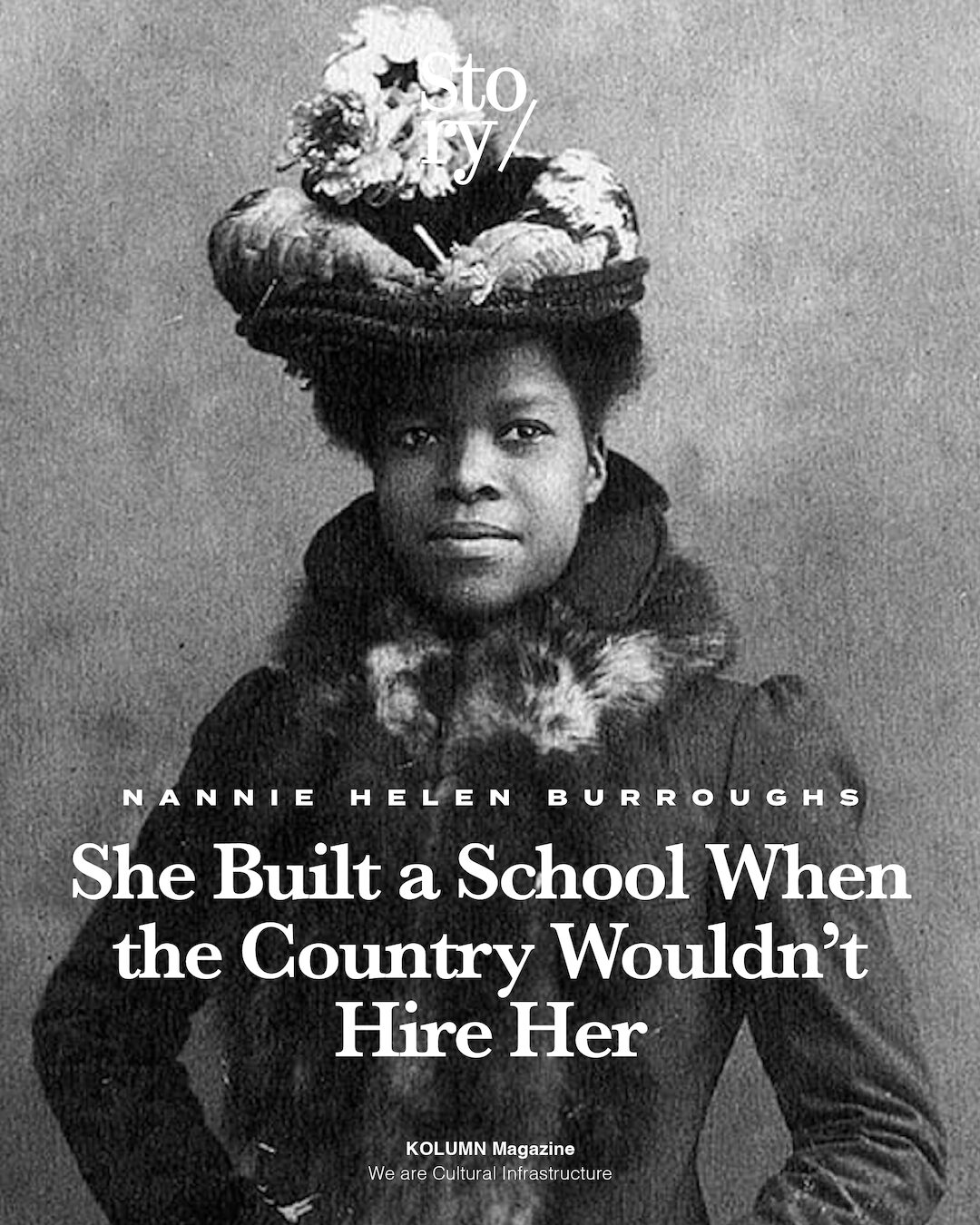

She Built a School When the Country Wouldn’t Hire Her