The debate over reparations has re-entered American politics. At congressional hearings, primary debates and across social media many people are talking about what reparations could look like and who might get them. [mc4wp_form id=”6042″]

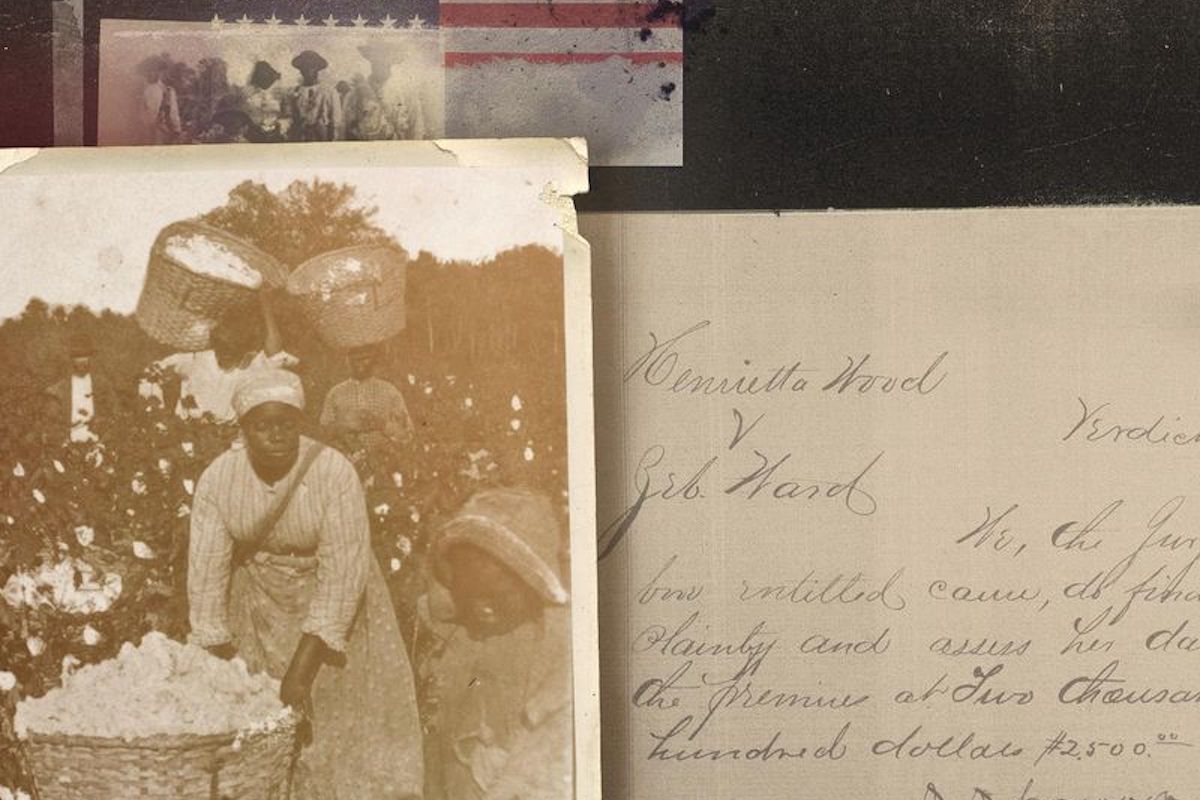

But the story of Henrietta Wood, a formerly enslaved woman who sued for restitution and won is missing from the discussion. Her little-known victory offers lessons for today, both about the impact restitution can make and about the limited power of payment alone.

In 1853, Wood was a free black woman living and laboring as a domestic worker in Cincinnati when she was lured across the Ohio River and into the slave state of Kentucky by a white man named Zebulon Ward. Ward sold her to slave traders, who took her to Mississippi. A cotton planter bought her there and later took her to Texas, where she remained enslaved through the Civil War.

Wood eventually returned to Cincinnati, and in 1870 sued Ward for $20,000 in damages and lost wages. In 1878, an all-white jury decided in Wood’s favor, with Ward ordered to pay $2,500, perhaps the largest sum ever awarded by a court in the United States in restitution for slavery.

Jim Crow Laws

Jim Crow laws were state and local laws that enforced racial segregation in the Southern United States. All were enacted in the late 19th and early 20th centuries by white Democratic-dominated state legislatures after the Reconstruction period. The laws were enforced until 1965. In practice, Jim Crow laws mandated racial segregation in all public facilities in the states of the former Confederate States of America and other states, starting in the 1870s and 1880s. Jim Crow laws were upheld in 1896 in the case of Plessy vs. Ferguson, in which the U.S. Supreme Court laid out its “separate but equal” legal doctrine for facilities for African Americans. Moreover, public education had essentially been segregated since its establishment in most of the South after the Civil War (1861–65).

The legal principle of “separate but equal” racial segregation was extended to public facilities and transportation, including the coaches of interstate trains and buses. Facilities for African Americans and Native Americans were consistently inferior and underfunded compared to the facilities for white Americans; sometimes, there were no facilities for people of color. As a body of law, Jim Crow institutionalized economic, educational, and social disadvantages for African Americans and other people of color living in the South.

Jim Crow laws and Jim Crow state constitutional provisions mandated the segregation of public schools, public places, and public transportation, and the segregation of restrooms, restaurants, and drinking fountains for whites and blacks. The U.S. military was already segregated. President Woodrow Wilson, a Southern Democrat, initiated the segregation of federal workplaces in 1913.

In 1954, segregation of public schools (state-sponsored) was declared unconstitutional by the U.S. Supreme Court under Chief Justice Earl Warren in landmark case Brown v. Board of Education. In some states, it took many years to implement this decision, while the Warren Court continued to rule against the Jim Crow laws in other cases such as Heart of Atlanta Motel, Inc. v. United States (1964). Generally, the remaining Jim Crow laws were overruled by the Civil Rights Act of 1964 and the Voting Rights Act of 1965.

Wikipedia

You must be logged in to post a comment.