KOLUMN Magazine

A Woman

the World Couldn’t Look Away From

The Story of Ella Abomah Williams

By KOLUMN Magazine

In October 1865, just months after the 13th Amendment formally abolished slavery in the United States, a baby girl named Ella Grigsby was born in Laurens County, South Carolina. Her parents were formerly enslaved Black Southerners navigating the fragile, violent in-between of Reconstruction, when freedom was a promise more than a practice. Decades later, that same girl would stride through European boulevards and Antipodean port towns as “Mme Abomah, the African Giantess,” advertised as the tallest woman in the world, a living spectacle of Black womanhood, empire, and modern entertainment.

This is the story of Ella Abomah Williams: a woman whose extraordinary height turned her into a global celebrity, and whose life reveals how Black performers negotiated dignity, money, and myth in a world determined to turn their bodies into commodities.

Growing up in the shadow of slavery

Ella’s exact birthdate is debated, but most sources agree she was born in October 1865 near Cross Hill in Laurens County, South Carolina, to parents who had been enslaved. The surname she carried, Grigsby, came from the family that once owned her parents—a reminder that even in freedom, the architecture of slavery lingered in names, land, and local power.

As a teenager, Ella left her family home to work for Elihu and Harriet Williams, a white couple in Columbia, South Carolina. She eventually took their surname, a move historians believe was a deliberate refusal to carry the name of enslavers into her adult life. It was an early act of self-definition: she could not choose how tall she would grow, but she could choose, at least in part, who she would be called.

Sometime around age 14, Ella contracted malaria. One recurring detail in later press coverage and reminiscences is that the illness somehow triggered a rapid growth spurt. Whether malaria was truly causal is medically uncertain, but by her late teens Ella was already towering above those around her. Contemporary publicity materials claimed she stood 7 feet 6 inches; a closer look at comparative photographs suggests a still-astonishing height closer to 6 feet 10 or 6 feet 11.

In Columbia, she worked primarily as a cook and domestic worker. Showmen—circus recruiters and vaudeville managers—began to appear at her door, offering contracts to “tour the world” as a giantess. For years, Ella refused. “For years every time a show man saw me he would want me to sign a contract, but I never could make up my mind to leave Columbia,” she later recalled in a 1915 interview.

That reluctance matters. At a time when Black women’s bodies were routinely exploited without consent—from medical theaters to carnival “freak shows”—Ella understood that signing her name meant surrendering control over both her labor and her image.

Becoming “Mme Abomah”: a global act built on myth

The turning point came in the fall of 1896. Frank C. Bostock, an ambitious British showman whose enterprises mixed wild animal shows, circuses, and novelty acts, arrived in Columbia. Bostock was skilled at spinning racialized, imperial fantasies for white audiences on both sides of the Atlantic. He recognized that Ella’s height, combined with her composure and striking presence, could anchor a profitable act. This time, the offer was convincing. She signed.

Bostock and his publicity team promptly reinvented her.

Ella Grigsby/Williams of South Carolina was reintroduced to the world as “Mademoiselle Abomah,” a supposed warrior from the legendary Dahomey Amazons—an all-female regiment from the West African kingdom of Dahomey (in present-day Benin). Her stage name was drawn from Abomey, Dahomey’s capital. Posters and cabinet cards described her as “the African Giantess,” “Amazon Giantess,” and “the tallest woman in the world,” often pairing her with diminutive white men or children to amplify the visual contrast.

The fiction was thick:

She was said to be eight feet tall, though photographic analysis suggests otherwise.

She was billed as a “Dahomey warrior,” despite being born and raised in South Carolina.

Posters often placed her in exoticized costume, with feathered headpieces and beaded gowns that evoked a generic, imagined “Africa” rather than any specific culture.

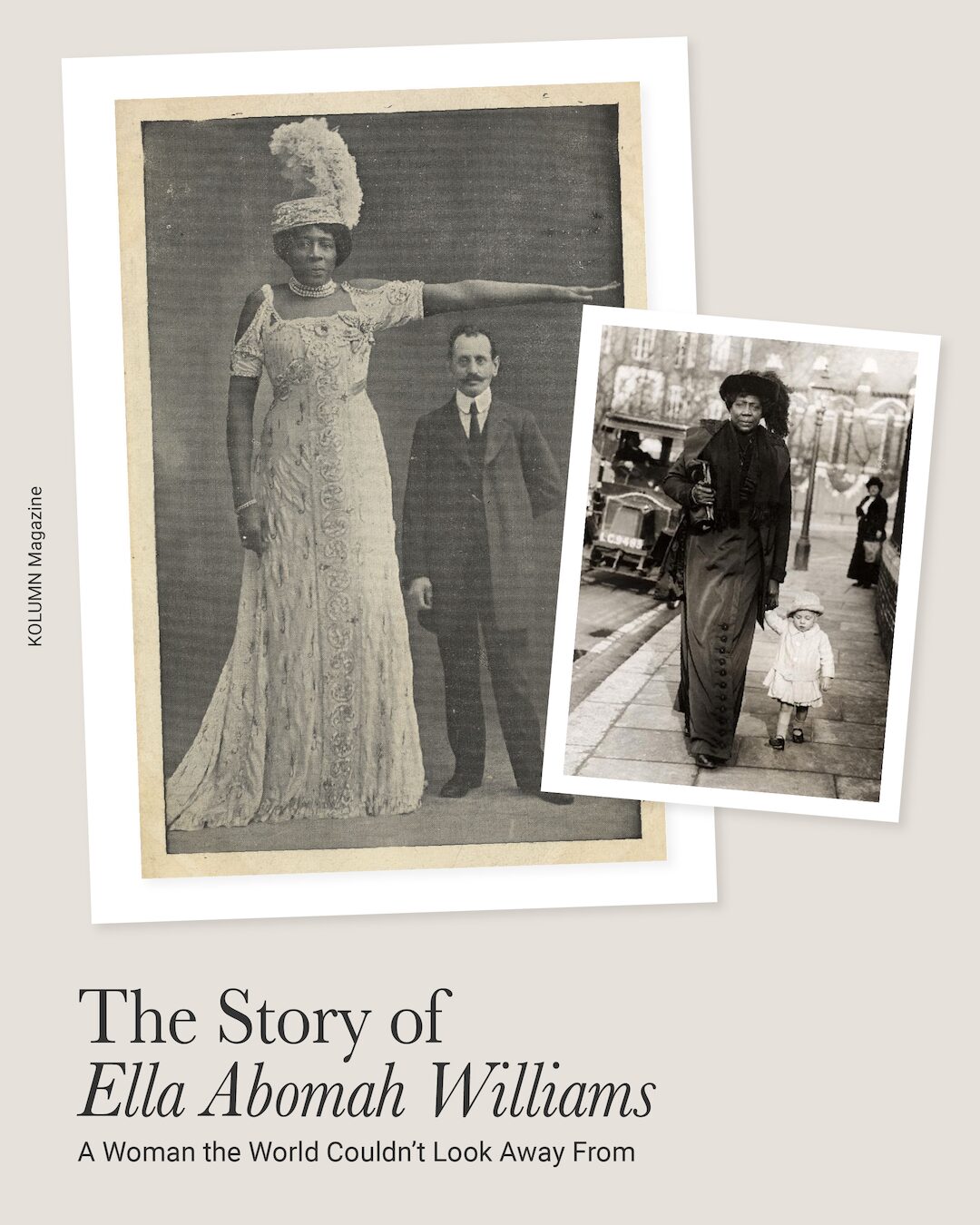

Yet Ella’s participation in this mythmaking was not purely passive. She insisted on a wardrobe that was elegant and expansive, with high-necked dresses, gloves, and elaborate hats that gave her a regal bearing rather than the monstrous look favored by many “freak show” managers. In publicity photos, she often stands composed and dignified, towering but poised, a Black woman claiming space in a world designed to minimize her.

On the road: Britain, Europe, and the global circuits of spectacle

Ella’s first major tour with Bostock took her to Britain around 1896–1900. Press accounts from the period describe audiences lining up to see the “coloured giantess” in cities like Liverpool, Blackpool, and London. In an era when the British empire was at its zenith, Abomah’s act fed directly into imperial curiosity: here was a woman framed as a warrior from a far-off African kingdom, now tamed and displayed in the heart of the empire.

Her performances typically combined posing and song. Contemporary reports note that she sang minstrel and popular songs of the era, often numbers written with racist caricatures of Black people. Like many Black entertainers trapped within the structures of minstrelsy and vaudeville, she navigated a brutal calculus: in order to work and be paid, she had to perform material shaped by white fantasies about Blackness.

But audiences also saw something else: a Black woman who, despite the constraints of the scripts handed to her, carried herself with dignity. In photographs from this period, she looks directly at the camera, shoulders squared, clothing meticulously arranged.

From Britain she moved outward along the circuits of global popular entertainment:

Australia (1903) – Posters and news reports trailed her across towns where touring shows were central to public life.

New Zealand (1904–1908) – Newspapers in Dunedin and elsewhere marveled that she “completely dwarfed” those around her yet moved with surprising grace, highlighting both her height and her stagecraft.

South America (1909) – She toured with Reynolds’s Waxworks and Exhibitions, a traveling show that blended static displays with live acts.

Cuba and Coney Island (1910s) – In 1917 she appeared at Coney Island, at that time a dense marketplace of human curiosities, thrill rides, and mass entertainment.

By the mid-1910s, Ella Abomah Williams had become one of the most traveled Black women in the world. Her routes shadowed colonial shipping lines and global circuits of entertainment, showing how Black performers both exploited and were constrained by imperial infrastructures.

A body as business

While there is no surviving ledger of her earnings, contemporary accounts suggest that Ella did well for herself during her peak touring years. Later reports, including a 1928 obituary in the Tampa Morning Tribune, noted that she was “well-off” at the time of her death.

In the absence of traditional bank records or personal correspondence, we can read her financial story through the choices she made and the spaces she occupied:

Wardrobe as investment – Her gowns were described as “expensive and extensive,” tailored to emphasize length and elegance rather than freakishness. That level of costuming required sustained income and suggested she understood her clothing as both armor and marketing.

Managerial relationships – She worked with major firms including Reynold’s Waxworks, Ringling Brothers, and Barnum & Bailey. Those contracts, however unequal, placed her within the top tier of novelty and circus performers.

Global bookings – Touring across continents was expensive; promoters did not move acts that didn’t draw consistent crowds. Her sustained presence on billings across Europe and the Americas suggests she was a reliable draw and likely negotiated pay increases as her fame grew.

We don’t know which banks, if any, she used to manage her earnings—a sharp reminder of how Black financial histories are often harder to reconstruct than the spectacle of Black bodies in public. What is clear is that Ella, like many Black performers of her era, turned the thing that made her vulnerable—her unusually tall body—into a source of income and mobility.

At the same time, she was locked inside a system that made her financial security contingent on continually offering herself up for display. The same advertisements that gave her global visibility also erased her origins, rebranding her as an exotic African warrior rather than a Black American woman born in the crucible of Reconstruction.

Race, gender, and the spectacle of height

Ella’s story sits at the intersection of several powerful forces: race, gender, disability, and the economics of “difference.”

Race and empire

European and American audiences interpreted her height through racialized lenses. In London, advertisers emphasized her supposed African origin, linking her to the Dahomey Amazons, who had already been sensationalized in ethnographic shows and human zoos.

This framing turned her from an individual with a specific life story into a generalized symbol of African otherness. That erasure was not just rhetorical; it shaped the kinds of roles she could play and the scripts she could perform.

Gender and respectability

As a Black woman whose body defied conventional femininity, Ella walked a narrow line between curiosity and threat. Her managers often emphasized her stylishness and refinement as a way to soften the shock of her size. Posters and photos show her in high-fashion gowns, dripping with beads and lace, often holding flowers or a fan—symbolic props of ladylike decorum.

At the same time, the very premise of her act relied on the destabilizing effect of her presence: she was a woman larger than most men, a visual challenge to gender hierarchies. Reviews commented not only on her stature but on her grace, as if surprised that someone so large could move with elegance.

Disability and the “freak show” economy

Though historical sources don’t frame her height as a disability, Ella worked squarely within an industry that categorized non-normative bodies as “freaks.” The same circuits that booked her also featured people with dwarfism, conjoined twins, bearded women, and others whose bodies had been medicalized or stigmatized.

Ella’s ability to command respect in this environment—through demeanor, dress, and the control she exerted over her self-presentation—marks her as an agent within, rather than simply a victim of, the freak show economy. But that agency operated within harsh limits defined by racism, colonialism, and ableism.

War, homecoming, and the long fade from the spotlight

The outbreak of World War I in 1914 abruptly reconfigured the entertainment circuits that had carried Ella across continents. With Britain at war, she canceled her tours and returned to the United States in early 1915.

Back home, she continued to work, but the landscape was changing. She joined Ringling Brothers and Barnum & Bailey in 1918, appearing in their “Congress of Freaks,” and later took engagements at Coney Island sideshows and attractions like Dreamland and the World’s Museum.

These bookings suggest a shift from the relatively glamorous international tours of her earlier career to more stationary, and likely less lucrative, work in American amusement venues. Age, competition from younger acts, and perhaps health issues tied to her size may all have played a role.

By the 1920s, the public record thins out. She appears sporadically in circus rosters and local press notices, but the details of her day-to-day life—where she lived, who she loved, how she spent her money—are largely absent from the archive.

What we do know is this: according to cemetery records and reprinted newspaper reports, Ella Abomah Williams died in 1928 in Hawaii, where she was likely working with a traveling show or circus. She was in her early 60s. A Find A Grave entry lists her birth as October 1865 in South Carolina and her death in Hawaii, confirming the broad arc of her journey from Reconstruction-era South to the far Pacific.

Reading between the posters

For much of the 20th century, Ella’s story survived primarily in carnival lore, mislabeled photos, and sensationalist blog posts—many of which repeated dubious claims about her exact height or origins. Recent work by independent researchers, local historians, and Black history projects has begun to correct the record, grounding her life in the realities of Reconstruction and Jim Crow rather than the fantasies of the circus poster.

By cross-referencing:

Census records and family-tree databases,

Newspaper archives from New Zealand, Britain, and the United States,

Circus and exhibition programs, and

Photographic evidence,

researchers now place Ella firmly as a South Carolina–born Black woman who leveraged her extraordinary height into a 30-year career that took her around the world.

The corrections matter. They reclaim her from the caricatures of show business, restoring her as a historical actor shaped by, but not reducible to, the fantasies woven around her.

Legacy: towering beyond the frame

Today, images of Ella Abomah Williams circulate widely on social media and in Black history forums: the woman in the feathered hat striding down a European street; the giantess gently extending her arm above a smaller white companion; the stately figure in a lace gown framed by studio props.

They often appear with captions marveling at her height, but less frequently do they ask: What did it mean for a Black woman born to formerly enslaved parents to command that much attention in London, Dunedin, Havana, or Coney Island at the turn of the 20th century?

Ella’s life invites us to consider:

Black mobility – She traveled further than most Americans of her generation, especially most Black Southerners. Her journeys complicate narratives that portray Black life in this period as geographically static.

Self-fashioning – She curated her image through clothing and demeanor, pushing back against demeaning representations even as she worked within a system built on them.

Economic survival – In a world that offered Black women few respectable avenues to wealth or independence, she turned a stigmatized trait into a livelihood that appears to have left her financially secure at her death.

We will likely never have the intimate details: whether she sent money home to family in South Carolina, how she felt about the endless gawking, whether she ever wished to be ordinary-sized. The archive preserves her most clearly at the moments when she was most objectified—captured in studio portraits, ticket lines, and promotional copy.

Even so, across time and myth, certain facts hold steady. Ella Abomah Williams was born into a world that saw Black women as property. She lived long enough to see her own image printed and reprinted across continents, a face and form people paid to witness. She refused, at least early on, to be taken on someone else’s terms, and when she finally did step onto the world’s stages, she did so dressed in the visual language of royalty.

In the end, the tallest lady in the world was also something else: a Reconstruction-born Black woman who learned to navigate the treacherous economies of spectacle, standing—quite literally—head and shoulders above the systems that tried to define her.