Geoffrey Holder and the Art of Living Without Boundaries

By KOLUMN Magazine

Geoffrey Holder liked to say you couldn’t label him “like a can of soup.” He was right. Over eight decades, the Trinidad-born artist moved through the worlds of dance, theater, painting, fashion, film, music, and advertising with a kind of joyful insistence that Black life—Caribbean, urban, diasporic—was worthy of spectacle and seriousness all at once. He was a Tony-winning director and costume designer, a balletic giant on Broadway, a villain in a James Bond film, the resonant voice behind a soft drink campaign, and a painter whose canvases now hang in major collections.

This is the story of how Geoffrey Lamont Holder, born in colonial Port of Spain, built a life that refused to fit in anyone else’s frame.

Port of Spain: An “enchanted” childhood

Geoffrey Holder was born on August 1, 1930, in Port of Spain, Trinidad, one of several children in a middle-class family of Barbadian and Trinidadian descent. His father, Arthur, was “a salesman of everything,” forever arriving home with fabrics and curiosities; his mother, Louise, turned those fabrics into clothes. The house brimmed with color, texture, and rhythm.

The gravitational center of Geoffrey’s early world, though, was his older brother Boscoe. A prodigy as painter, pianist, and dancer, Boscoe founded the Holder Dancing Company and drafted seven-year-old Geoffrey into its ranks.

Growing up under Boscoe’s wing, Geoffrey absorbed a total conception of art. In a later recollection, he described his adolescence as “like living under the wing of the Wizard of Oz,” remembering mornings listening to Boscoe play Chopin, afternoons heady with the scent of turpentine from his brother’s canvases, evenings spent watching rehearsals.

But the boy who would one day mesmerize Broadway also struggled to speak. As an adult, Holder recalled a debilitating stammer that made classroom reading an ordeal. “I used to stammer to the point where I couldn’t speak at all,” he remembered; the laughter of classmates pushed him away from language toward movement, line, and color.

Dance and painting became, quite literally, his first fluent languages.

By his mid-teens, Holder was exhibiting his paintings in Trinidad. Local critics called him a “boy wonder,” and the national press held him up as an example to aspiring artists. When Boscoe left for Europe, Geoffrey—still barely out of adolescence—took over the Holder Dancing Company, leading a troupe that grafted Caribbean folk forms onto modern dance.

Those early years fixed two constants that would define his life: the dense, sensory world of Trinidad—its Carnival, its street music, its vernacular Catholic-African spirituality—and the model of artistic polymathy embodied by his brother.

Crossing water: New York calls

The bridge from Port of Spain to New York City came through yet another legendary choreographer: Agnes de Mille. In the early 1950s, de Mille saw Holder’s company perform in the Caribbean—accounts vary whether in Puerto Rico or St. Thomas—and urged him to bring his work to the United States.

To finance the move, Holder sold a cache of his paintings, then boarded a ship north. He arrived in New York in 1953, already an established artist back home, but very much an immigrant starting over.

New York, in his telling, was a revelation: a city of music leaking from windows and “stylish ladies tripping down Fifth Avenue” whose glamour thrilled the young Trinidadian artist.

He began teaching at the Katherine Dunham School of Dance and Theatre, immersing himself in a community of Black and Caribbean modernists who were reimagining what American dance could be. In 1954, he made his Broadway debut in House of Flowers, the Truman Capote–Harold Arlen musical set in the Caribbean. There he shared a stage with Alvin Ailey, Diahann Carroll, and Pearl Bailey—and met a young California-born dancer named Carmen de Lavallade.

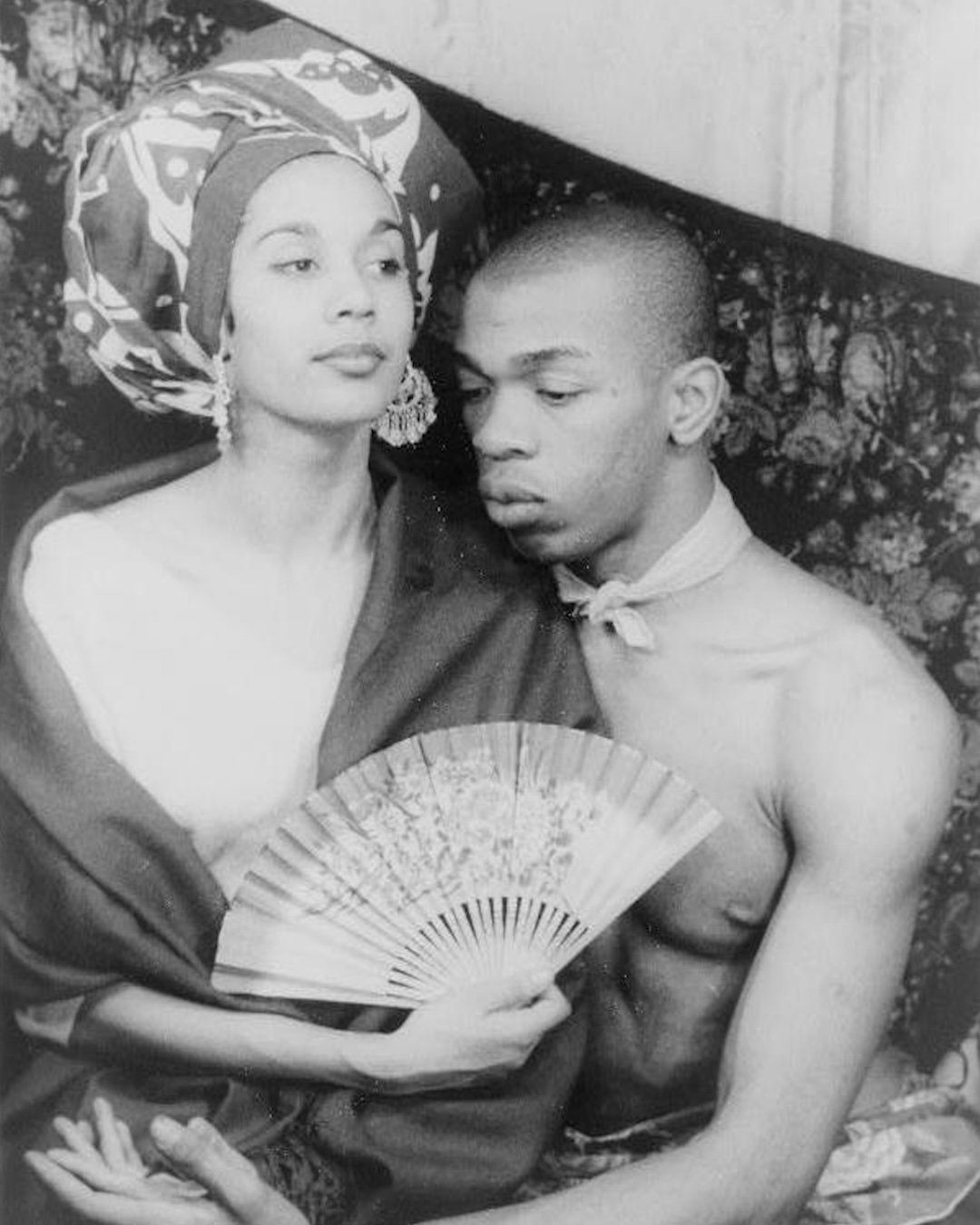

Onstage, House of Flowers gave Holder a showcase for his balletic strength and flamboyant stage presence. Offstage, it changed his life. Holder proposed to de Lavallade four days after they met; she said yes a month later. They married in 1955, beginning one of the longest and most storied partnerships in American dance.

“She is the most beautiful woman in my world,” he would later say. “God gave me a muse, and her name is Carmen.”

They were partners in every sense: she, a technically dazzling modern dancer steeped in Lester Horton and Alvin Ailey; he, a towering, theatrical stylist with an eye for design and ritual. Together they toured, created work, raised their son Léo, and navigated the racial obstacles of mid-century American stages.

Ballet, Godot, and an expanding canvas

Even as he built a life in theater, Holder pursued a classical ballet career. From 1955 to 1956 he danced as a principal with the Metropolitan Opera Ballet, one of the few Black artists in such a prominent position within a major U.S. institution at the time.

He also moved into straight drama. In 1957, he appeared in an all-Black production of Waiting for Godot, bringing his distinctive physicality to Samuel Beckett’s existential stage.

The painter in him never went away. In 1956 he received a Guggenheim Fellowship in fine arts, and his work was exhibited at institutions including Washington’s Corcoran Gallery and later the Guggenheim Museum. His paintings—elongated figures, intense color fields, and sensual portraits—often returned to the Caribbean bodies and atmospheres of his youth, echoing the work of his brother Boscoe, with whom he maintained a rich correspondence.

Critics and curators now speak of the Holder brothers as ahead of their time: artists who insisted on the Black body as a site of beauty, desire, and complexity decades before mainstream institutions began to catch up.

The cinema of charisma: Baron Samedi & the “uncola”

Holder’s film career began modestly with roles in the jazz-inflected drama All Night Long (1962) and the big-budget musical Doctor Dolittle (1967). But it was his 1973 turn as Baron Samedi in the James Bond film Live and Let Die that sealed his fame with global audiences.

Costumed in top hat and skull makeup, Holder played the Vodou-linked spirit of death with a mix of menace, humor, and supernatural cool that walked a fraught line between stereotype and subversion. His Baron Samedi is shot, fed to snakes, and yet reappears grinning at the film’s end, a figure beyond the control of colonial logic.

Off camera, Holder helped choreograph the film’s ritual scenes. When told he’d be expected to fall into a coffin full of live snakes despite his phobia, he nearly refused—until he was informed a British royal, Princess Alexandra, would be visiting the set that day. Ever the showman, he took the plunge.

If Baron Samedi made him a cult figure, a series of commercials made him mainstream. In the 1970s and ’80s, Holder became the pitchman for 7Up, the “uncola.” In a white suit, with his towering height and Caribbean lilt, he held a glass of soda up to the camera and purred that it was “crisp and clean, and no caffeine… never had it, never will.”

For many TV viewers, especially Black and Caribbean American families, those ads were more than marketing; they were encounters with a kind of unapologetic Black elegance rarely seen in mainstream advertising. In a pop culture landscape that often relegated Black men to either servility or threat, Holder’s persona—eccentric, aristocratic, amused—quietly rewrote the script.

He continued to take varied roles: Punjab, the loyal bodyguard in Annie (1982); a sly supporting turn in Eddie Murphy’s Boomerang (1992); the voice of Ray the Sun on children’s show Bear in the Big Blue House; narrator in Tim Burton’s Charlie and the Chocolate Factory (2005).

“The Wiz” and the politics of spectacle

If film made Holder visible, Broadway cemented his legacy.

In 1975, he directed and designed costumes for The Wiz, a soulful, urban reimagining of The Wizard of Oz with an all-Black cast. The show’s yellow brick road was a neon fantasy of Afrofuturist possibility; its Munchkins and Emerald City citizens moved with the swagger of Harlem and the Caribbean; its Wicked Witch and Wiz were as much products of Black political history as fairy tale.

Holder’s work on The Wiz won him two Tony Awards—for Best Direction of a Musical and Best Costume Design—making him the first Black man nominated, and the first to win, in either category. The show ran for 1,672 performances, toured widely, and helped usher in a generation of Black musical theater talent.

Colleagues recall his rehearsal room as equal parts atelier and carnival. He might sketch a costume between notes on choreography or sing a line himself to coax more flavor from a performer. Dancers from Alvin Ailey American Dance Theater and Dance Theatre of Harlem, for whom he created such works as The Prodigal Prince and Dougla, remember a director who insisted on theatricality but never at the expense of human depth.

In Dougla, Holder drew on Afro-Trinidadian wedding rituals within the island’s Afro-Indian (“dougla”) communities, costuming dancers in elaborate white and feathered headdresses and staging processions that merged Carnival spectacle with liturgical gravitas. For Ailey, he fused Haitian folklore with modern technique, creating a mythic world whose visual density critics compared to painting.

These works were not simply colorful entertainment. They were interventions in what Black bodies could mean on the concert stage: not just instruments of social realism or protest, but vessels of fantasy, spirituality, and erotic charge.

Love, collaboration, and daily life

Behind the flamboyance was a quieter story of partnership and discipline. Holder and de Lavallade built a home in New York filled with art—his own canvases, Caribbean sculpture, African masks collected on tour. Photographs from the 1960s show him seated in a modernist chair, glass in hand, surrounded by objects that testify to a global, Black visual culture long before such aesthetics became fashionable.

Their love story is inseparable from his art. De Lavallade appears repeatedly in his paintings—elongated neck, luminous skin, gowns that seem to float off the canvas. She appears, too, in the archive they left behind, acquired in 2018 by Emory University’s Rose Library: letters between Geoffrey and Boscoe, rehearsal videos, costume sketches for The Wiz, and decades of correspondence with fellow artists.

“We are not in competition with each other,” de Lavallade once said. “He let me do what I wanted to do.”

Friends recall their home as a salon of sorts, where younger Black dancers, actors, and painters could see a working model of an artistic life shared, not sacrificed, to partnership and family.

Holder also mentored a younger generation of Caribbean and Black American artists who saw in him permission to be multiple—to refuse the narrowing that often comes with institutional acceptance.

Breaking frames: Fashion, masculinity, and Black beauty

Part of Holder’s power lay in the way he used his own body as a kind of moving artwork. Standing 6-foot-6 with a shaved head, he favored long coats, sweeping scarves, and large rings. Contemporary stylists now cite him as a reference for “dandyism,” but his look was more idiosyncratic: a merging of Carnival flamboyance, European tailoring, and modernist minimalism.

His fashion sense, along with his paintings and choreography, helped expand the range of Black masculinities visible in public life. In a world that often forced Black men into narrow roles—athlete, criminal, comic relief—Holder presented an alternative: sensual, cerebral, playful, sometimes camp, and unafraid of ornament.

The Guardian, writing about a recent London exhibition of the Holder brothers’ work, noted how their paintings of Black men and women, many nude, “represented blackness as beautiful” decades before such imagery was widely accepted in mainstream Western art spaces.

In this sense, Holder’s career can be read as a sustained project of re-seeing: training audiences to regard Black bodies, Caribbean rituals, and diasporic aesthetics not as exotic curiosities, but as sources of modernity and sophistication.

Later years: Archives, honors, and reflection

In his later years, Holder continued to paint and occasionally perform. In 1990, he sang “Under the Sea” and “Kiss the Girl” from The Little Mermaid at the Academy Awards, his booming voice filling the telecast with Caribbean lilt.

He narrated documentaries, voiced characters in children’s programs, and remained a sought-after presence in dance and theater circles. His works entered private collections and galleries; exhibitions like “Renaissance Man: The Art and Life of Geoffrey Holder” at the Museum of the City of New York and later shows in London positioned him alongside other 20th-century modernists.

Meanwhile, scholars of performance and Black studies began to treat his choreography and design as crucial to understanding the aesthetics of the Black Arts movement, even if he often occupied more commercial spaces than explicitly radical ones.

His marriage to de Lavallade endured, a rarity in the brutal economies of show business. They were the subject of the 2005 documentary Carmen & Geoffrey, which captured their shared history with affection and candor: rehearsals, archival footage, quiet scenes at home.

On October 5, 2014, Holder died in New York City from complications of pneumonia, at the age of 84. Tributes poured in from across the arts: Alvin Ailey alumni, Dance Theatre of Harlem veterans, Broadway peers, Caribbean cultural figures, and ordinary fans who remembered him from 7Up commercials.

In Trinidad, newspapers honored him as a national son whose work carried the island’s rhythms onto global stages.

Legacy: What Geoffrey Holder left us

To tally Geoffrey Holder’s achievements is straightforward enough:

Principal dancer with the Metropolitan Opera Ballet.

Tony Awards for direction and costume design for The Wiz, the first Black artist to win in those categories.

Iconic film roles, especially Baron Samedi in Live and Let Die, and a pop-cultural afterlife in advertising as the 7Up “uncola” man.

Seminal choreographic works like Dougla and The Prodigal Prince for major Black dance companies.

A substantial body of visual art, now collected and exhibited internationally.

But the deeper measure of his life lies in how he stretched the available imagination.

For Black artists struggling to break into institutions that alternately exoticized or excluded them, Holder’s career offered proof that one could be both rooted and experimental, Caribbean and cosmopolitan, commercial and uncompromisingly individual. His very presence—in rehearsal studios, in galleries, on primetime TV—challenged the rigid taxonomies of high and low art, of “serious” and “popular” culture.

He insisted that art could be lush, excessive, and pleasurable without surrendering its seriousness. He showed that a Black immigrant from a small Caribbean island could remake the visual language of Broadway and Madison Avenue alike.

And for audiences—those who watched The Wiz from the balcony, who saw Dougla at Dance Theatre of Harlem, who caught his 7Up commercials between sitcoms—he offered something subtler but perhaps more lasting: a glimpse of Black life rendered as marvelous, in his own favored pronunciation, “maaah-velous.”

In an era when many artists brand themselves as multi-hyphenates, Geoffrey Holder’s life reads less like a résumé and more like a manifesto. Not just that one person can do many things, but that Black creativity, given room, will overflow any container built to hold it.