KOLUMN Magazine

A Legacy

Preserved

Shonda Rhimes’ $1.5M Gift

Protects Till Murder Site

By KOLUMN Magazine

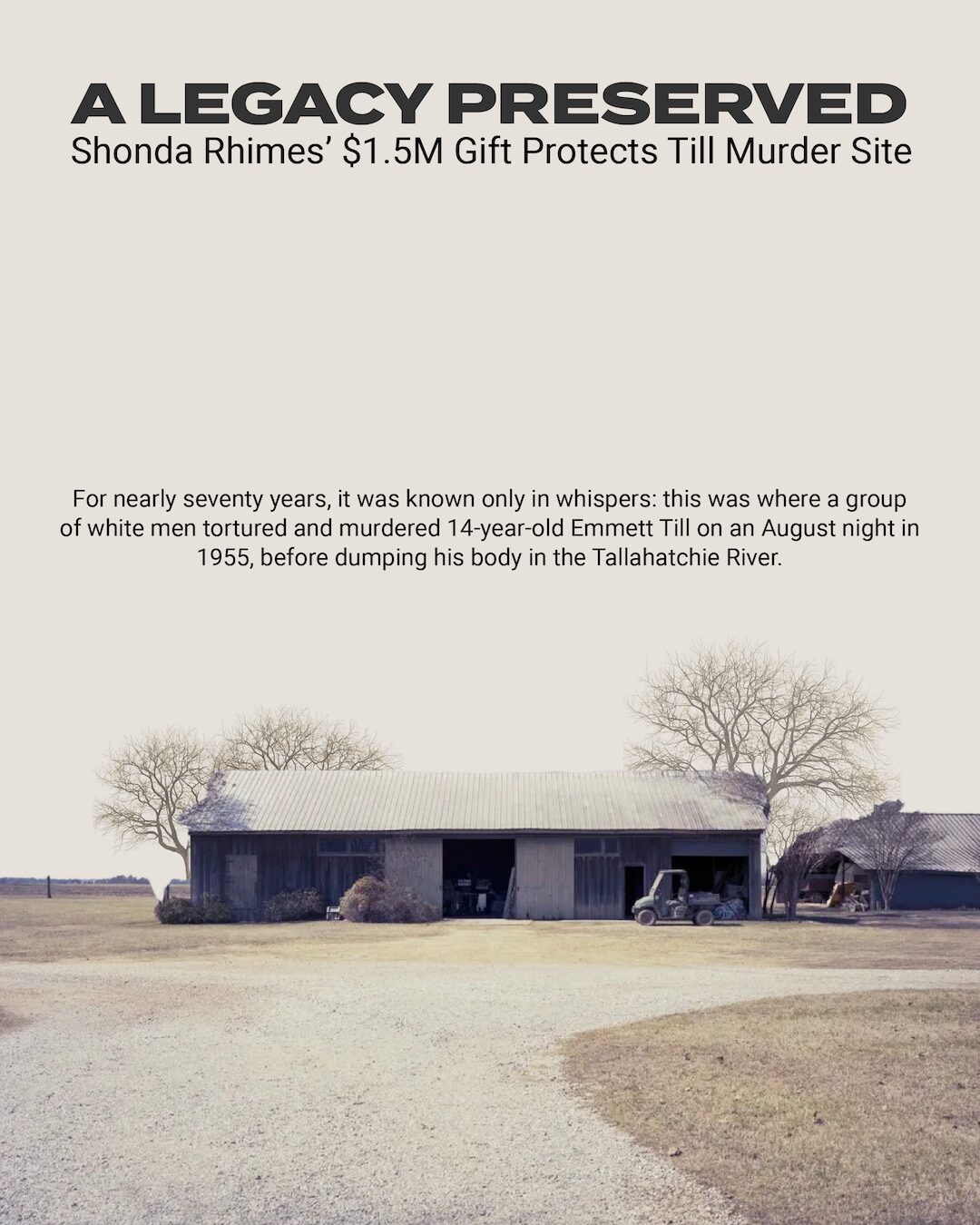

The barn stands low and weathered against the flat Mississippi Delta sky, a simple wooden structure at the end of a gravel road outside the town of Drew. For nearly seventy years, it was known only in whispers: this was where a group of white men tortured and murdered 14-year-old Emmett Till on an August night in 1955, before dumping his body in the Tallahatchie River.

Now, that barn has a new future.

Backed by a $1.5 million gift from television producer and writer Shonda Rhimes, the Emmett Till Interpretive Center (ETIC) has purchased the property and plans to open it to the public as a “sacred site” by 2030, in time for the 75th anniversary of Till’s lynching.

For Rhimes, whose series like Scandal, Grey’s Anatomy and Bridgerton have made her one of the most influential storytellers in modern television, the acquisition is more than an act of philanthropy. It is a profound bet that owning the land where racial terror took place is essential to telling the full truth about America — and to deciding who gets to tell it.

“My hope is that this story never gets lost,” Rhimes said on Good Morning America when she first announced her passion project to help preserve Till sites, including the barn.

A long-hidden crime scene

Emmett Till’s name has long been synonymous with the brutality of Jim Crow and the spark of the modern Civil Rights Movement. In August 1955, the Chicago teenager traveled to Mississippi to visit relatives. Days later, a white shopkeeper, Carolyn Bryant, accused him of whistling at and making advances toward her at Bryant’s Grocery in Money, Mississippi.

In the early hours of August 28, Roy Bryant and his half-brother J.W. Milam abducted Till from his great-uncle Moses Wright’s home. They and other men drove him through the Delta to a seed barn on the Milam family plantation outside Drew. There, according to later confessions and historical research, they beat and tortured the boy before shooting him in the head. His mutilated body was found days later in the Tallahatchie River, weighted with a cotton gin fan strapped to his neck.

An all-white jury quickly acquitted Bryant and Milam of murder. Protected from retrial by double jeopardy, the pair later admitted in a paid magazine interview that they had indeed killed Till.

But even that confession left out a crucial detail: the barn itself. As scholar Dave Tell notes, the site was deliberately written out of the story “by the very men who committed the crime,” erasing the physical setting of the torture from public memory and obscuring the number of people involved.

For decades, the barn remained in private hands, used mostly for storage. No historical marker indicated what had happened there. There were no visitors’ hours, no educational displays. It existed as a kind of ghost infrastructure of white violence — present in the landscape, absent from the official record.

A movement to remember, born of apology

The effort to reclaim that history began not in Los Angeles or Washington, but in Tallahatchie County itself. In 2007, more than fifty years after Till’s lynching, local Black and white residents gathered on the courthouse lawn in Sumner, the same courthouse where Bryant and Milam had been acquitted, and issued a public apology for the county’s role in the miscarriage of justice.

Out of that apology grew the Emmett Till Memorial Commission and, eventually, the Emmett Till Interpretive Center, housed across the street from the courthouse. The center’s mission is bluntly stated on its website: “Racial reconciliation begins by telling the truth.”

Over the last two decades, ETIC has stitched together a fragile but expanding network of remembrance:

Restoring the Tallahatchie County Courthouse where Till’s killers walked free.

Marking Graball Landing on the Tallahatchie River, widely believed to be where Till’s body was pulled from the water — and replacing that marker repeatedly after it was defaced, shot and vandalized so many times that the latest version is now bulletproof.

Partnering with the National Park Service as an official nonprofit partner of the Emmett Till and Mamie Till-Mobley National Monument, created by President Joe Biden in 2023.

The barn, however, remained unresolved. In 1994, a local white farmer, Jeff Andrews, bought the property that included the barn. When he learned its history, he quietly began allowing members of Till’s family, scholars and visitors to spend time at the site. But he continued to use it as a working structure; it was never protected as a historic place.

For ETIC and its allies, the question was urgent: what would happen if Andrews sold the property?

“Because erasure is a form of violence”

By 2020s, the barn was deteriorating. The beams sagged. The roof needed work. The land beneath it — in a region where power still often tracks who owns the “dirt,” as writer Wright Thompson puts it — was increasingly valuable.

The Emmett Till Interpretive Center spent years exploring ways to secure the site: asking for a donation of the property, considering easements, even researching eminent domain. None proved viable. In the end, ETIC’s board confronted a stark choice.

“Doing nothing would allow a sacred witness to collapse,” the center wrote in an open letter explaining the purchase. “We could not risk this site — one of the most sacred in American history — falling into the hands of speculators or even hate groups.”

The price was $1.5 million, a staggering sum for a small nonprofit in rural Mississippi.

“We did not want to have to pay for sacred ground,” the center acknowledged. “But we chose preservation over risk, and truth over silence — because you can’t put a price on our history.”

That is where Shonda Rhimes enters the story.

How a magazine story changed Shonda Rhimes’ philanthropy

Rhimes has spoken openly about the moment Emmett Till’s story — and specifically, the barn — lodged in her mind. In 2021, she read Wright Thompson’s Atlantic article “The Barn,” a deeply reported piece on the long effort to find, document and protect the site where Till was tortured. She realized she had never been taught precisely where the murder had occurred.

“I don’t think I had ever known where it happened, where a child had been tortured and killed,” Rhimes later told Good Morning America. “I couldn’t let it go. I kept thinking about it for weeks afterwards.”

By 2023, she had turned that unease into a concrete project: teaming up with ETIC to help preserve key sites connected to Till’s story, including the barn in Drew. She described the work as transformative, saying it changed how she thought about charitable giving and “even preserving history.”

Rhimes channeled her support through the Rhimes Family Foundation, a private grantmaking foundation she created in 2017. Public filings show the foundation makes multi-million-dollar grants each year, with a focus on education, the arts and equality; recipients have included the Smithsonian’s National Museum of African American History and Culture and other cultural institutions.

According to ETIC’s barn FAQ and reporting from Mississippi Today, leadership support from the Rhimes Family Foundation allowed the nonprofit to meet the full $1.5 million purchase price, ensuring the barn would not be sold to private developers or those who might exploit its notoriety.

For Rhimes, whose television shows have often centered Black characters fighting to control their own narratives, the symbolism is acute. “History is always told by the victors,” she said on GMA. “And I think that it’s important that the Till family is the victor in this story.”

A site of terror becomes a site of conscience

With the purchase complete, ETIC now holds legal title to the barn and surrounding property, but its leaders are quick to stress that they see themselves as caretakers rather than owners.

“Our role is not possession, but protection — serving as caretakers on behalf of the community and the nation,” the center explains.

The transformation ahead is substantial. Before the barn can fully open to the public, ETIC plans to:

Stabilize and preserve the structure to prevent further collapse.

Design the memorial in deep consultation with descendants, local residents and national partners, including the Till family and the National Park Service.

Develop interpretation and visitor access, integrating the barn into a larger network that includes the courthouse in Sumner, Graball Landing and other sites.

The goal is to open the barn as part of a larger public memorial by 2030. ETIC envisions a place where visitors come not to gawk at tragedy but to “confront their own role in the ongoing work of democracy” — a sacred site of conscience rather than a macabre attraction.

The barn will have 24-hour security, a lesson learned from years of vandalism against Till memorials in the Delta. Historical markers near places tied to his death have been stolen, thrown into the river, defaced with acid and repeatedly shot; one sign marking the riverbank had to be replaced with a bulletproof steel version.

Voices from Mississippi

To understand what the barn’s preservation means, it is necessary to listen to the people who live closest to it.

For decades, residents of Drew and surrounding communities have carried the weight of what happened that night in 1955 without the world fully seeing them.

“The barn’s preservation means our voices, our land and our legacy will finally be part of how the world remembers Emmett Till — and how it learns from him,” said Gloria Dickerson, a Drew-based community leader, in ETIC’s open letter.

Young people in the Delta are already grappling with that legacy. In 2023, student filmmakers worked with the Emmett Till Interpretive Center and public radio reporters to document Till’s story on film. One 16-year-old from nearby Philips, Mississippi, described the shock of standing in front of the barn she had driven past all her life. “It kind of puts you in a new light,” she said. “Like, ‘Oh, I live right across from this place.’”

For members of Till’s family, the barn is both sacred ground and a source of unresolved questions. Deborah Watts, co-founder of the Emmett Till Legacy Foundation, welcomed the preservation but said she wants to ensure the family’s concerns are central in plans for the site. “We consider that area sacred ground where Emmett was murdered,” she said.

Keith Beauchamp, the filmmaker behind The Untold Story of Emmett Louis Till and a producer of the 2022 feature film Till, called the acquisition “significant” precisely because it holds both healing and pain. Preserving the barn, he argued, means acknowledging an American history many would prefer to forget.

Philanthropy, land and the politics of memory

Rhimes’ gift arrives at a moment when the United States is fiercely debating how — or whether — to teach young people about the history of racist violence. Book bans, attacks on diversity programs and efforts to limit discussions of systemic racism in schools have all intensified in recent years.

In that context, the acquisition of a lynching site through private philanthropy raises both hopeful and uneasy questions.

On one hand, the Rhimes Family Foundation’s investment offers an example of how wealthy donors can support grassroots, community-driven institutions rather than imposing their own narratives. ETIC has been doing the slow work of truth-telling and reconciliation in Tallahatchie County for nearly twenty years. Rhimes is stepping into an existing movement, not inventing one.

On the other hand, the very fact that a civil-rights site as significant as the Till barn had to be “rescued” through a private fundraising campaign underscores the gaps in public will. The barn is not currently part of the official Emmett Till and Mamie Till-Mobley National Monument, though ETIC expects to coordinate closely with the National Park Service.

Davis Houck, director of the Emmett Till Archives at Florida State University, has described the privately funded purchase as a “most generous gift — to the community of Drew, to the state of Mississippi, and ultimately to the entire nation.” At the same time, he and others note that relying on philanthropy to secure truth-telling sites is inherently precarious.

Writer Wright Thompson, whose article first caught Rhimes’ attention and who later published the book The Barn: The Secret History of a Murder in Mississippi, frames it in terms of land. In the Delta, he argues, history is told — and erased — through who owns the fields, barns and houses: “Who owns it, who farms it, who lived and died on it, whose ghost is trapped in it.” Rhimes’ gift, he said, means “the dirt has been reclaimed, and once reclaimed, the slow process of cleaning the blood from it can begin.”

A barn, a boy, and the future of American memory

The barn outside Drew is still quiet. For now, there are no ticket booths, no glossy exhibits. But even in its present state, the building holds a different charge: it is no longer just a private structure where a crime took place, but a public site of conscience.

When it opens by 2030, visitors will be able to stand where Emmett Till stood, to feel the claustrophobic darkness described by students and historians who have been inside. They will arrive in a country where the photograph of his mutilated body, once published in Jet and the Chicago Defender, circulates on smartphones; where John Lewis’s description of Emmett Till as “my George Floyd” resonates in the wake of new videos of police killings.

What they encounter at the barn will depend on decisions being made now — by local residents, by the Till family, by educators, by the small staff of the Emmett Till Interpretive Center, and yes, by donors like Shonda Rhimes whose money can change what is possible.

Rhimes, for her part, has framed her involvement not as an act of celebrity rescue, but as a responsibility grounded in her vocation. She makes her living telling stories about power, justice and the lives of Black people onscreen. Here, in the Mississippi Delta, she is helping to ensure that one of the most important stories in American history can never again be pushed offstage.

The barn will never be just a barn again. It will be a place where the country comes to ask itself the questions ETIC poses in its own materials: How far have we come? How much work remains? And what does it mean, in this moment, to refuse erasure — to insist, as Mamie Till-Mobley once did when she ordered her son’s casket opened, that the world must see?