No products in the cart.

KOLUMN Magazine

The

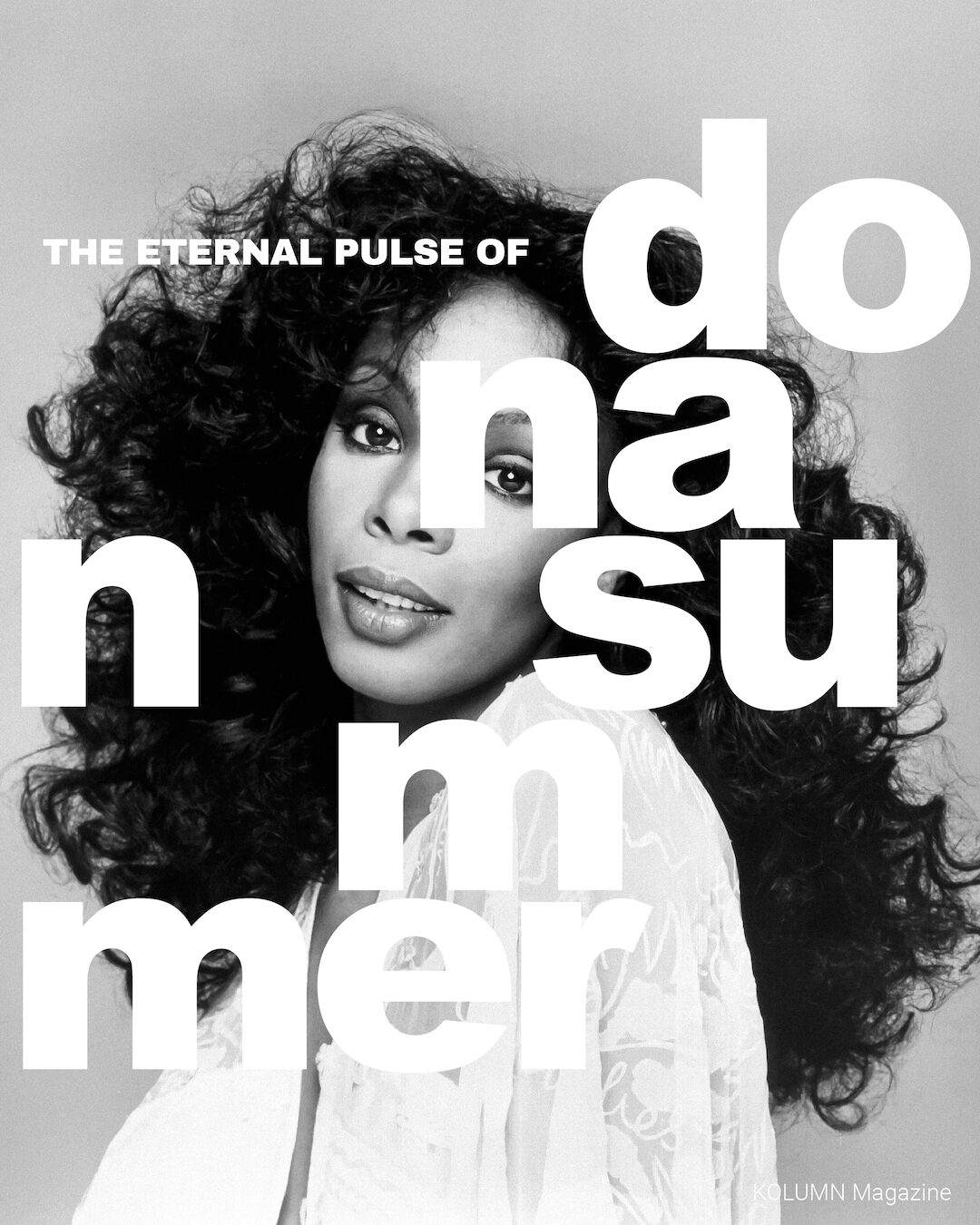

Eternal Pulse of Donna Summer

By KOLUMN Magazine

On a good sound system, “I Feel Love” still sounds like tomorrow.

The kick drum is a heartbeat, the bassline a liquid loop of synthesizer notes that never quite resolves. Above it all, Donna Summer’s voice rises and falls—pure, cool, and strangely weightless. When Giorgio Moroder first played the track in a New York club in 1977, Brian Eno reportedly told David Bowie he’d just heard the future. Decades later, critics still use almost the same language.

Summer’s catalog is so bound up with the history of disco that it’s easy to treat her as shorthand for an era: the mirror-ball queen, the sultry poster on the wall. But behind those hits was a working Black woman navigating a punishing industry, wrestling with faith and fame, and reinventing herself again and again. Her best songs trace that journey—from breathy sensuality to spiritual struggle, from club euphoria to working-class anthems.

This is the story behind those records, and how they changed pop music for good.

From Boston Choirgirl to Munich Studio Rat

LaDonna Adrian Gaines was born in Boston on December 31, 1948, one of seven children in a devout, working-class family. Her father was a butcher, her mother a schoolteacher; church was non-negotiable.

Her first taste of public acclaim came at ten, when she stepped in for a missing soloist at church. In her memoir Ordinary Girl: The Journey, Summer recalls the congregation falling silent, then erupting in applause—a moment that left her certain music would be her life.

By the late 1960s, she’d joined a psychedelic rock band, moved to New York, and landed a role in the countercultural musical Hair. When producers cast her in the German-language production, she relocated to Munich, learned German, and spent years grinding in theater and studios: Hair, Godspell, Show Boat, demo sessions, background gigs.

That hustle put her in the orbit of producers Giorgio Moroder and Pete Bellotte. Together, they built a sound that would come to define the global disco era—and lay the groundwork for electronic dance music.

The First Breakthrough: “Love to Love You Baby”

In 1975, the trio recorded a track initially meant as a demo: “Love to Love You.” Moroder and Bellotte wrapped Summer’s feather-light voice in strings, guitar, and a slow, throbbing groove. Casablanca Records founder Neil Bogart heard it at a party and demanded a much longer version, stretching it to a 17-minute suite that would fill the A-side of an album and the dance floors of the world.

On paper, the song is simple. In practice, it was explosive. Summer’s vocal—half-whispered, filled with simulated moans—sparked outrage on conservative radio and endless think-pieces about morality. At the same time, it handed her a global hit and the “First Lady of Love” marketing hook that would cling to her for years.

In Ordinary Girl, she writes candidly about the ambivalence that came with that success: the pride of authorship (she co-wrote the song), the financial lift for her family, but also the discomfort at being turned into a soft-focus sex symbol. She describes watching audiences respond to an image that didn’t quite feel like her, a tension that grew as the hits piled up.

Still, “Love to Love You Baby” changed the language of pop. It put unapologetic female pleasure—voiced by a Black woman—at the center of a major-label record. And it announced Donna Summer as more than just another club singer; she was the face of disco’s ascendancy.

“I Feel Love”: The Future Arrives

If “Love to Love You Baby” made her famous, “I Feel Love” made her immortal.

For the 1977 concept album I Remember Yesterday, Moroder and Bellotte decided each track would nod to a different era of popular music. The last song, they agreed, should sound like the future. So they turned to a Moog synthesizer, abandoning almost all traditional instrumentation. The result was “I Feel Love”: a fully electronic dance track with spiraling sequenced bass, metronomic hi-hats, and Summer’s voice floating like vapor above the machine.

The recording was technically tricky. Early Moogs drifted out of tune, so engineers had to record in short sections, constantly retuning the instrument and syncing everything to a click track—still a relatively novel technique in pop at the time.

Critics today see “I Feel Love” as a pivot point in music history. The Guardian ranked it among the greatest UK No. 1 singles of all time, calling it a turning point where “hypnotic synth, peerless vocals and visionary ambition” fused into something truly timeless. Rolling Stone placed Summer’s work prominently in its list of the greatest dance songs ever, and club culture histories routinely cite “I Feel Love” as a foundational text for techno, house, and EDM.

Beyond its technical impact, the song meant liberation for many of the people who embraced it first. Queer clubgoers in New York, Chicago, and beyond took its endless pulse and ecstatic vocal as an invitation to inhabit the dance floor as a place of safety and self-invention. Recent scholarship and documentaries, including HBO’s Love to Love You, Donna Summer, emphasize how essential Black and queer audiences were in building the Donna Summer mythos long before the industry caught up.

The Golden Run: Bad Girls, Power Ballads, and Duets

By the late 1970s, Summer was no longer just a disco star; she was a pop powerhouse capable of working across genres.

“Last Dance” (1978)

Written by Paul Jabara for the film Thank God It’s Friday, “Last Dance” begins as a ballad and then, in one of the great structural swerves in pop, explodes into full-tilt disco. The song won an Academy Award and a Grammy, and it became one of her signature live numbers.

Even now, “Last Dance” often closes out weddings, Pride parties, and retro nights. Its enduring appeal lies in the emotional arc Summer pulls off in four minutes: from loneliness to hope, from “I need you” to “this time I want to stay.” It’s not just a dance track; it’s a story.

Bad Girls (1979), “Hot Stuff” and “Bad Girls”

Summer’s 1979 double album Bad Girls is arguably her masterpiece. Rolling Stone included it in its 500 Greatest Albums of All Time, praising its range and ambition.

“Hot Stuff” bolted a distorted rock guitar riff onto a disco chassis. The gamble paid off: the song hit No. 1 in the U.S. and won Summer a Grammy for Best Female Rock Vocal Performance—proof she could thrive well beyond the confines of the genre critics were already declaring a fad.

The title track, “Bad Girls,” is equally striking. Inspired in part by sex workers she saw near her label’s offices, it layers handclaps, whistle blasts, and a chant-ready chorus over lyrics that refuse to moralize. Instead, Summer sketches vivid, sympathetic portraits of women doing what they have to do to survive. In the late 1970s, to put that story—of street-level, often Black and brown women—at the center of a major pop hit was quietly radical.

The album moves seamlessly from strutting funk (“Walk Away”) to slow-burn torch songs (“Dim All the Lights”), showcasing a vocal instrument that could be husky one moment and operatic the next.

“On the Radio” and “No More Tears (Enough Is Enough)”

Released later in 1979, “On the Radio” folds heartbreak into a deeply ’70s idea of media: the radio as both jukebox and confessional. The track became another Top 10 hit and a natural showcase for Summer’s ability to turn simple melodies into cathartic epics.

Then came “No More Tears (Enough Is Enough),” a duet with Barbra Streisand that plays like a stage musical compressed into six minutes. Over a swelling arrangement, the two singers trade lines and ad-libs, building from wounded disbelief to shared fury and, finally, liberation. The single hit No. 1 in the U.S., cementing Summer’s status as a cross-format star—equally at home on R&B radio, pop stations, and in the burgeoning world of adult-contemporary playlists.

“She Works Hard for the Money” and the Working-Class Anthem

By the early 1980s, disco faced open hostility in the U.S., often drenched in racism, sexism, and homophobia. Summer’s response was not to retreat but to pivot.

In 1983 she released “She Works Hard for the Money,” a pop-rock anthem inspired by Onetta Johnson, a bathroom attendant Summer met at a Los Angeles restaurant. In interviews and in her memoir, she describes seeing Johnson asleep on a chair, exhausted mid-shift, and feeling compelled to tell her story.

The song turned into a working-class rallying cry: “She works hard for the money / so you better treat her right.” Its music video—featuring Summer in a waitress uniform, leading a chorus of women in service jobs—became one of the first by a Black female artist to go into heavy rotation on MTV.

Critically, “She Works Hard for the Money” marked a shift in how Summer used her platform. Where earlier hits had often centered romance, sex, and escape, this track put everyday labor—particularly women’s underpaid, undervalued work—at the core of the narrative. It anticipated a wave of feminist pop in the 1980s and ’90s that would treat wage work, not just love, as a worthy subject for an anthem.

Later Reinventions: “State of Independence” and “This Time I Know It’s for Real”

Summer never entirely stopped taking risks.

Her 1982 recording of “State of Independence,” produced by Quincy Jones, turned a Jon & Vangelis art-rock song into a gospel-inflected pop track with a who’s-who backing choir (Michael Jackson, Stevie Wonder, Dionne Warwick, and others). The single didn’t dominate U.S. charts, but it has enjoyed a long afterlife, sampled and referenced by house and pop producers who hear in it an early blueprint for the “choir over a beat” formula that would later flourish in dance music.

In 1989, Summer teamed up with British hitmakers Stock Aitken Waterman—then in their imperial phase with Kylie Minogue and Rick Astley—for “This Time I Know It’s for Real.” The song is all late-’80s gloss: brisk BPMs, bright synthesizers, and a sugar-rush chorus. It sailed into the Top 10 in both the U.S. and UK, proving that, nearly 15 years after “Love to Love You Baby,” Summer could still ride the cutting edge of pop production without losing her identity.

Behind the Hits: Faith, Depression, and Control

The public narrative of Donna Summer’s life has often focused on the glamorous highs—gold records, awards, sold-out shows. Her own account looks different.

In Ordinary Girl: The Journey, she recounts crippling depression at the height of her fame, including a suicide attempt, and a sense that the sexualized persona crafted for her early hits had spun beyond her control. Her turn to born-again Christianity around 1979 became both a personal lifeline and a source of tension with segments of her audience.

The recent documentary Love to Love You, Donna Summer, co-directed by her daughter Brooklyn Sudano and filmmaker Roger Ross Williams, leans into these contradictions. Through home movies, studio footage, and sometimes painful interviews, it offers a portrait of a woman torn between competing demands: faith and sexuality, family and the road, privacy and the public’s hunger for access.

The film underlines a point that’s easy to miss when we talk only about beats and hooks: Donna Summer’s greatest work often emerged precisely from these tensions. The push-pull between transcendence and pressure, between freedom and control, is audible in the way she sings—a soaring belt one moment, an intimate whisper the next.

Legacy: The Beat That Outlived the Backlash

Donna Summer died in 2012 at age 63, from lung cancer, at her home in Florida. Obituaries from major outlets stressed the breadth of her achievement: 14 Top 10 singles in the U.S., multiple Grammys, three consecutive double albums at No. 1, and a voice that “sailed over dance floors and leapt from radios” for more than a decade.

In 2013, she was inducted into the Rock & Roll Hall of Fame. Her songs continue to resurface on soundtracks, in commercials, and in remixes; DJs from Chicago to Berlin still deploy “I Feel Love” or “Hot Stuff” when they want to shock a crowd into euphoria. Rolling Stone and The Guardian have both placed her tracks high on their lists of the greatest dance and pop songs ever recorded, further cementing her place in the canon.

The story hasn’t stopped. Summer: The Donna Summer Musical brought her life to Broadway, framing her as three women at once—young “Duckling Donna,” peak-era “Disco Donna,” and reflective “Diva Donna”—to capture the way she was constantly performing different versions of herself. And her family has publicly discussed plans for a scripted biopic or limited series to follow the 2023 HBO documentary, underscoring that we’re still, collectively, figuring out how best to tell her story.

The Sound of a Life Lived Out Loud

It’s tempting to summarize Donna Summer with a single title: Queen of Disco. The phrase is catchy and, in some ways, earned. But it’s also too small.

Her best songs mark the evolution of a Black woman artist pushing against the boundaries of genre, image, and expectation. “Love to Love You Baby” carved out space for female desire in mainstream pop. “I Feel Love” reimagined what a dance track could be, helping to invent modern electronic music. “Last Dance,” “Hot Stuff,” and “Bad Girls” proved she could marry storytelling, virtuoso singing, and irresistible grooves. “She Works Hard for the Money” turned the spotlight onto women whose labor underwrote everyone else’s joy.

Taken together, they form more than a greatest-hits playlist. They’re a kind of sonic autobiography, each track capturing a different version of Donna Summer: the church girl, the studio perfectionist, the exhausted star, the born-again believer, the working mother, the enduring icon.

Listen closely, and the through line is clear. Beneath the strings and synths and four-on-the-floor drums is a voice insisting on its right to change, to complicate the story the world tries to tell about it. That, as much as any chart statistic or critical list, may be Donna Summer’s real legacy: the sound of a woman refusing to be just one thing, even as she gave the rest of us the soundtrack to dance like we already were free.