KOLUMN Magazine

The Protest Candidate

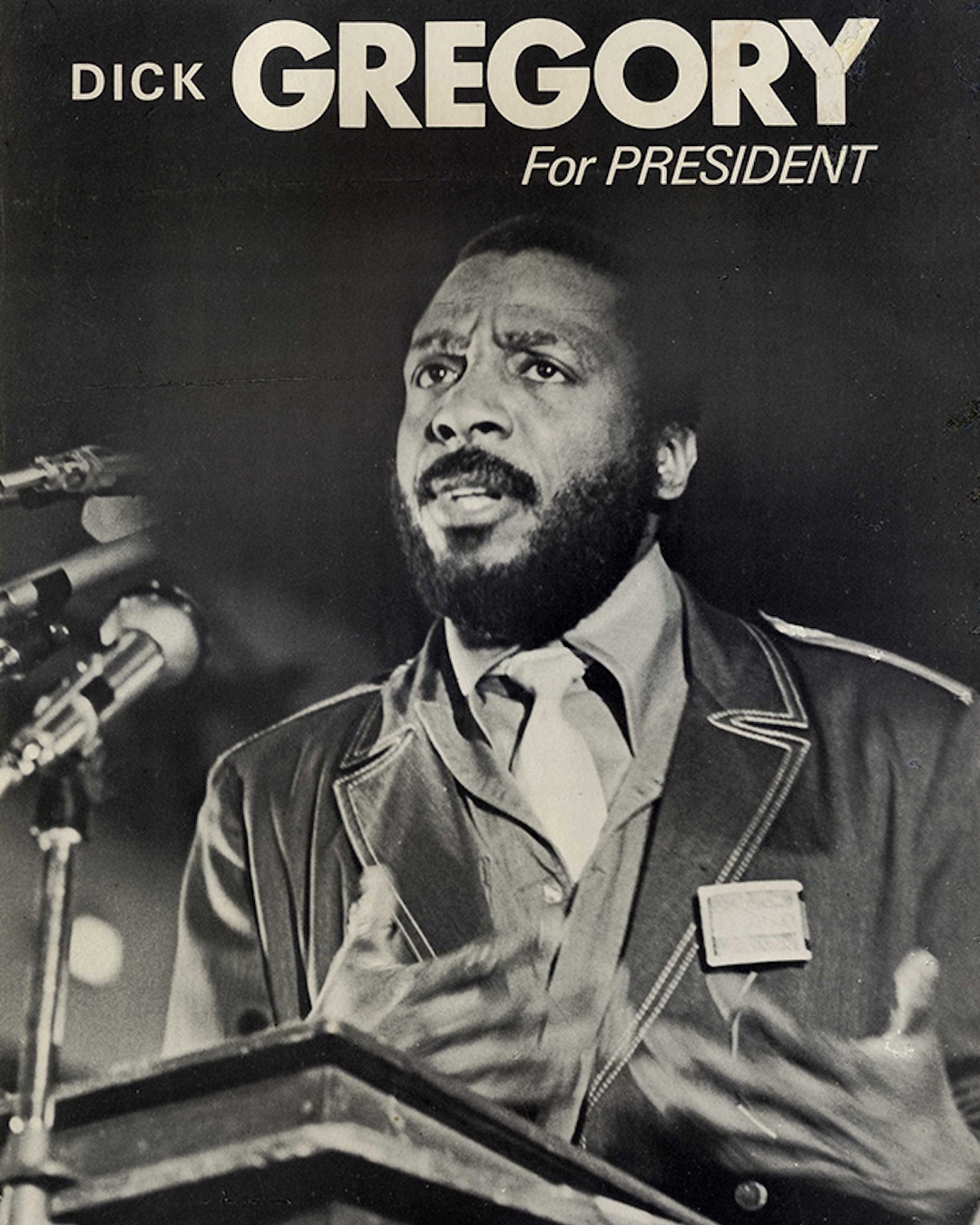

How Dick Gregory Turned a Write-In Campaign Into a Movement

By KOLUMN Magazine

In the long, tumultuous story of the 1968 presidential election, the camera usually stays locked on three men: Richard Nixon, Hubert Humphrey, and George Wallace. But if you widen the frame even a little, another figure comes into view — trim, bearded, in a field jacket or a rumpled suit, cracking jokes about racism and the war in Vietnam as he asks Americans to do something the political establishment insisted was pointless:

Write in “Dick Gregory” for president.

For tens of thousands of people — college students, draft resisters, Black sharecroppers’ children who had migrated North, working-class families in cities hollowed out by disinvestment — Gregory’s insurgent run was more than a stunt. It was a chance to register a protest against a country they felt was breaking faith with them, and to rally around a candidate who spoke their anger in a language of razor-edged humor and moral urgency.

Gregory knew he would not win. That was the point.

From St. Louis Hunger to a Platform Against Hunger

Richard Claxton Gregory was born in 1932 in St. Louis, the son of a single mother raising six children during the Depression. He ran track in high school and college, joined the Army, and then clawed his way into a segregated entertainment industry as a stand-up comic whose material refused to flatter white audiences. Instead, he turned the jokes back on Jim Crow America.

By the mid-1960s, Gregory had gone from nightclub headliner to full-time activist. He joined marches, sat-ins, and voter-registration drives across the South; he picketed segregated businesses and spoke at rallies against the Vietnam War and world hunger, often risking arrest.

One of the defining tools of his activism was his own body. Gregory repeatedly staged hunger strikes — sometimes lasting more than a month — to dramatize issues ranging from school desegregation to the war in Southeast Asia. In 1968, while serving a sentence in Washington State for a minor fishing violation he’d turned into a protest over Native treaty rights, he refused food for 39 days and was eventually removed from jail to a hospital because of his deteriorating health.

These experiences shaped his politics. When he looked at the 1968 presidential field — an incumbent Democratic administration mired in Vietnam, a Republican front-runner promising “law and order,” and a third-party segregationist — Gregory saw a race that, in his view, had little interest in hungry children in Mississippi or in Black teenagers facing police dogs in Chicago.

If the political system would not speak to them, he decided, he would.

From City Hall to the White House: A Comedian Turns Candidate

Gregory’s first formal step into electoral politics came in 1967, when he ran for mayor of Chicago against the powerful Democratic machine boss Richard J. Daley. He lost badly, but the campaign confirmed two things: that his name and reputation could draw crowds, and that the machinery of American politics was designed to keep someone like him out.

One year later, he aimed higher.

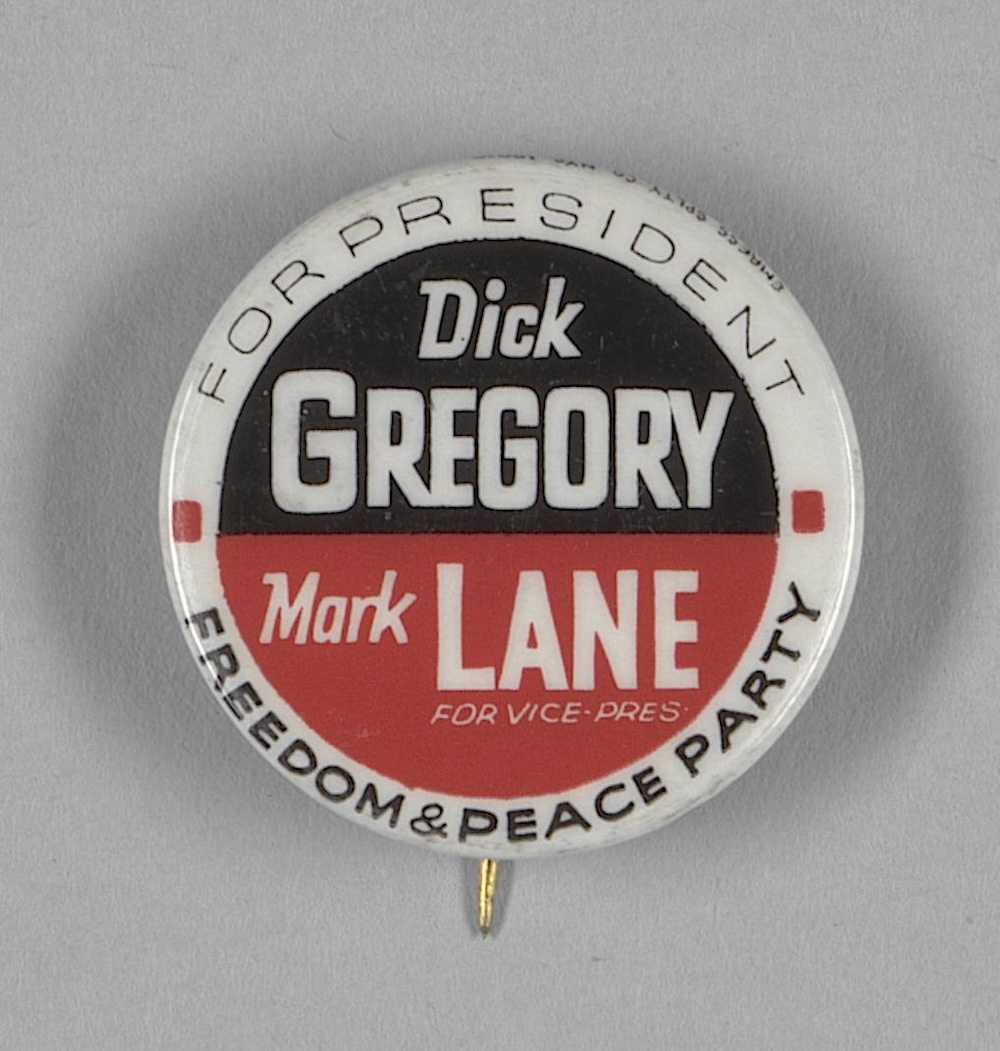

In the 1968 presidential race, Gregory became the write-in candidate for the Freedom and Peace Party — a small anti-war splinter of the Peace and Freedom Party. In some states he ran with civil-rights lawyer Mark Lane as his running mate; in others he was paired with figures like pediatrician Benjamin Spock or peace activist George Wallace (no relation to the Alabama governor).

The platform was simple and radical:

Immediate end to the Vietnam War

A frontal assault on racism in housing, policing, and education

Economic justice, including a focus on hunger and poverty at home

A challenge to the two-party system itself, which Gregory argued was incapable of delivering true democracy to disenfranchised communities

Mainstream media largely treated the campaign as a curiosity. One historian notes that columnists and commentators framed Gregory’s bid as an “entertaining sideshow,” a comic relief to an otherwise grim contest. But out on the trail, the response looked very different.

“Write Me In”: The Movement Behind the Candidate

Gregory’s rallies were equal parts stand-up act, political teach-in, and revival meeting. College campuses, particularly those roiled by anti-war protests, welcomed him as a kind of traveling conscience. Students lined up to hear him riff on Lyndon Johnson, Nixon, and the draft — and then pivot without warning into stories about starving children in the Mississippi Delta or the mothers of soldiers killed overseas.

On the South Side of Chicago, in Oakland, in Newark, his name meant something different than it did in the pages of the Washington Post. Here was a man who had marched in their streets, faced the same tear gas they had, spent nights in the same jails. Many working-class Black families, excluded from meaningful influence inside either major party, saw his candidacy as a way to say: We are here, and we are watching.

The campaign encouraged volunteers to treat the ballot as a political letter. Supporters were urged to hand-write “Dick Gregory” on their presidential line as a protest vote — a practice that often meant their ballots were counted, at best, as “miscellaneous” or “scattering,” if they were counted at all. Historians who have tried to reconstruct the tally suggest that the official numbers understate Gregory’s support, since many election offices didn’t bother to record write-in votes by name.

Still, enough of those protest ballots were counted to make a statistical impression. Nationwide, Gregory received 47,097 recorded votes, a tiny fraction of the more than 73 million cast that November — but a remarkable total for a candidate with no party machine, virtually no advertising budget, and limited access to the ballot.

For many of the people who wrote his name in, the impact was less about numbers than about the feeling of finally seeing themselves in the political arena. Oral histories and contemporary accounts describe Black veterans, young white anti-war activists, and working-class parents standing in line with Gregory buttons on their jackets, explaining to skeptical poll workers that yes, they realized he was not on the machine-printed ballot — and yes, they still wanted to vote for him.

Gregory later titled his book about the race Write Me In!, a nod both to the technicalities of his candidacy and to the broader demand: write people like us into the story of who America says it is.

Humor as Weapon, Currency as Prop

If Gregory lacked the money of a major campaign, he compensated with spectacle and wit.

One of his most famous tactics was a fake one-dollar bill. The “flyer” bore his portrait in place of George Washington’s; some were printed at such high quality that they briefly circulated in vending machines and cash drawers before the federal government scrambled to confiscate them.

Gregory loved to retell the story. The bills couldn’t possibly be mistaken for genuine U.S. currency, he joked — “Everyone knows a Black man will never be on a U.S. bill.” The line landed because it pinched the country’s contradictions: a democracy proud enough of its ideals to put leaders on its money, but unwilling to honor the Black people who had built its wealth.

The campaign’s printed literature often bore the slogan “Vote for Freedom and Peace — Vote Against Racism and War”, framing the race as a referendum not just on candidates but on the structural choices that had produced segregation at home and conflict abroad.

Campaign posters and buttons — some produced by volunteers, others by the tiny Freedom and Peace Party operation — became cherished artifacts. In later years, collectors would prize the “Dick Gregory for President” pins and the faux dollar bills as evidence of a moment when the protest politics of the street briefly crossed onto the official ballot.

Challenging the National Security Club

If Gregory’s candidacy was sometimes dismissed as humorous, the federal government did not treat it as a joke.

In May 1968, Gregory went to federal court in Washington, D.C., seeking an injunction against President Lyndon Johnson and top State Department officials. His complaint: major presidential candidates were receiving national security briefings, but he was being excluded. Gregory argued that as a declared candidate on enough state ballots to theoretically win the presidency, he was entitled to the same information.

He lost the case. But the lawsuit was part of a broader pattern. Gregory’s outspokenness on Vietnam, urban poverty, and police violence — amplified through his presidential run — helped land him on President Richard Nixon’s secret “enemies list,” a roster of people the administration considered political threats.

For supporters, this confirmed what they already believed: that the system would do almost anything to marginalize voices calling for a deeper reckoning with racism and war.

Living the Issues He Ran On

While Gregory was asking Americans to write his name in on their November ballots, he was also putting his body on the line in ways most candidates never would.

Throughout 1968, he continued to join demonstrations, fasts, and marches even as he campaigned. In an era when some politicians talked about “law and order” from podiums ringed with police, Gregory was often in the crowd facing those officers — or being loaded into the same paddy wagons as his supporters.

His critics dismissed this as theatrics. But many of the people who voted for him had watched him show up in their towns long before the presidential race — speaking at rallies against segregated schools, walking picket lines at grocery boycotts organized by groups like Operation Breadbasket, or visiting hunger-struck families whose names would never appear in a newspaper.

That continuity mattered. To them, Gregory’s campaign was not a vanity project; it was another front in a much larger struggle.

A Small Vote Total in a Huge Election — and a Long Shadow

On November 5, 1968, Richard Nixon narrowly defeated Hubert Humphrey, with George Wallace capturing a substantial share of the Southern vote on a segregationist ticket.

Gregory’s 47,097 recorded votes did not change the electoral outcome. They were less than one-tenth of one percent of the national total — a statistical footnote in one of the most consequential elections in modern U.S. history.

And yet, the longer arc of American politics tells a more complicated story.

His campaign helped normalize the idea of Black independent and protest candidacies on the national stage. Just four years later, Shirley Chisholm would run for the Democratic nomination as the first Black woman to seek a major-party presidential nod. A decade after that, the Reverend Jesse Jackson would mount his own insurgent bids, drawing on many of the same themes Gregory had hammered: war, poverty, racism, and the moral obligations of the state to its most vulnerable citizens.

Gregory’s run also anticipated a politics of disillusionment with the two-party system that continues to echo today. When contemporary activists critique Democrats and Republicans as equally captive to corporate or militarized interests, they are, in some ways, speaking Gregory’s language.

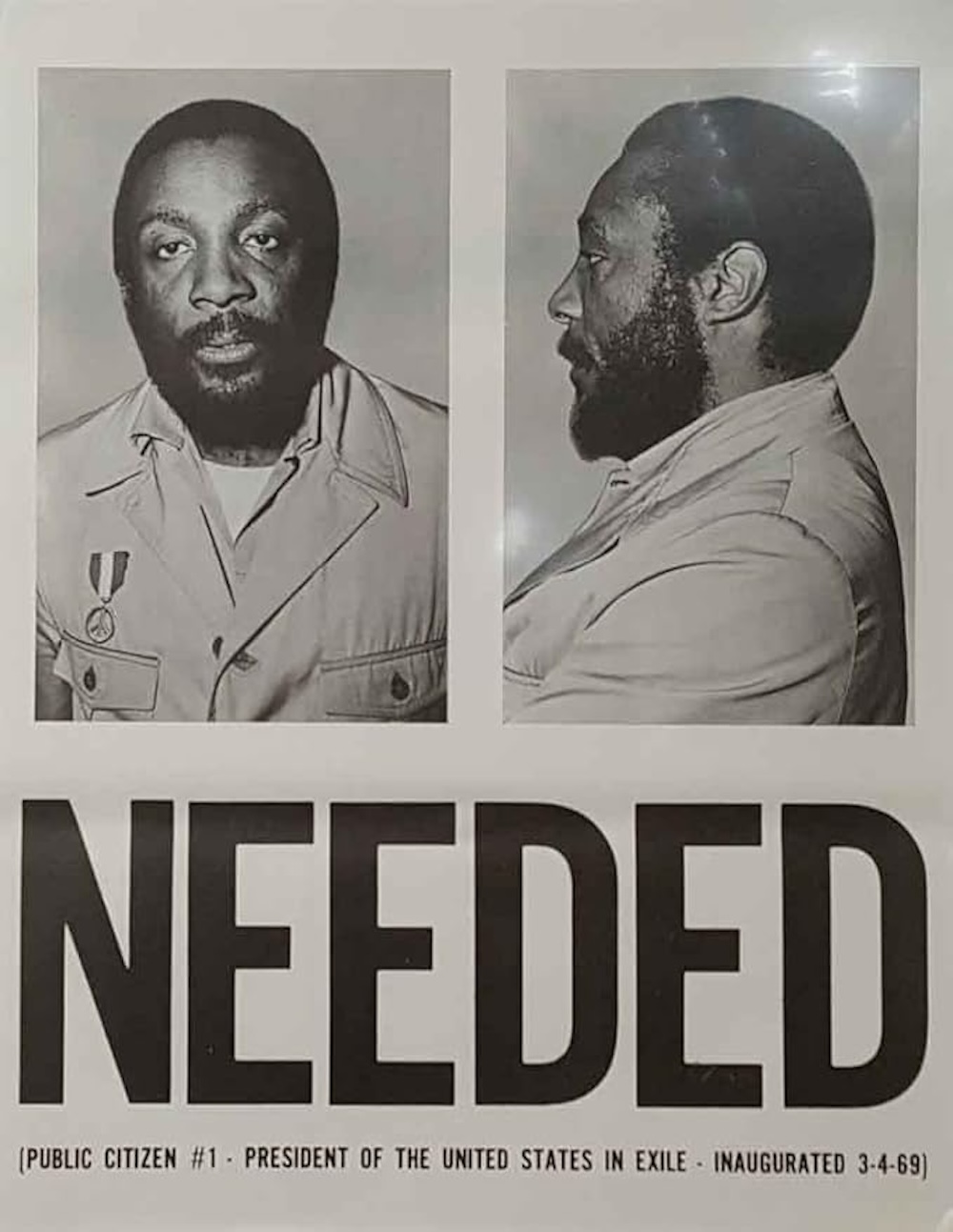

Remembering the “President in Exile”

In the years after 1968, Gregory sometimes referred to himself, half-jokingly, as the “President of the United States in Exile.” Historians of Black politics have taken the phrase seriously, seeing it as a way of naming the distance between the lived experiences of many Black Americans and the official story of the nation.

His presidential campaign did not deliver cabinet appointments or judicial nominations. What it offered instead — to the students who scribbled his name onto punch cards, to the parents who explained to their children why there was a different name on their sample ballot pinned to the refrigerator, to the elders who watched a Black man claim the right to the highest office in the land — was a practice run in imagining a different kind of democracy.

For those supporters, the act of writing in Dick Gregory was both small and enormous. It took only a second. It left the White House unchanged. But it also carved a tiny, personal record in the ledger of 1968 — a claim that they had refused to accept the choices they were given, and that they had, however modestly, written themselves into the story.

Half a century later, as voters once again debate the limits of the choices before them, Gregory’s campaign stands as a reminder that sometimes the most important races are not the ones that end in victory — but the ones that teach people what it means to demand more.