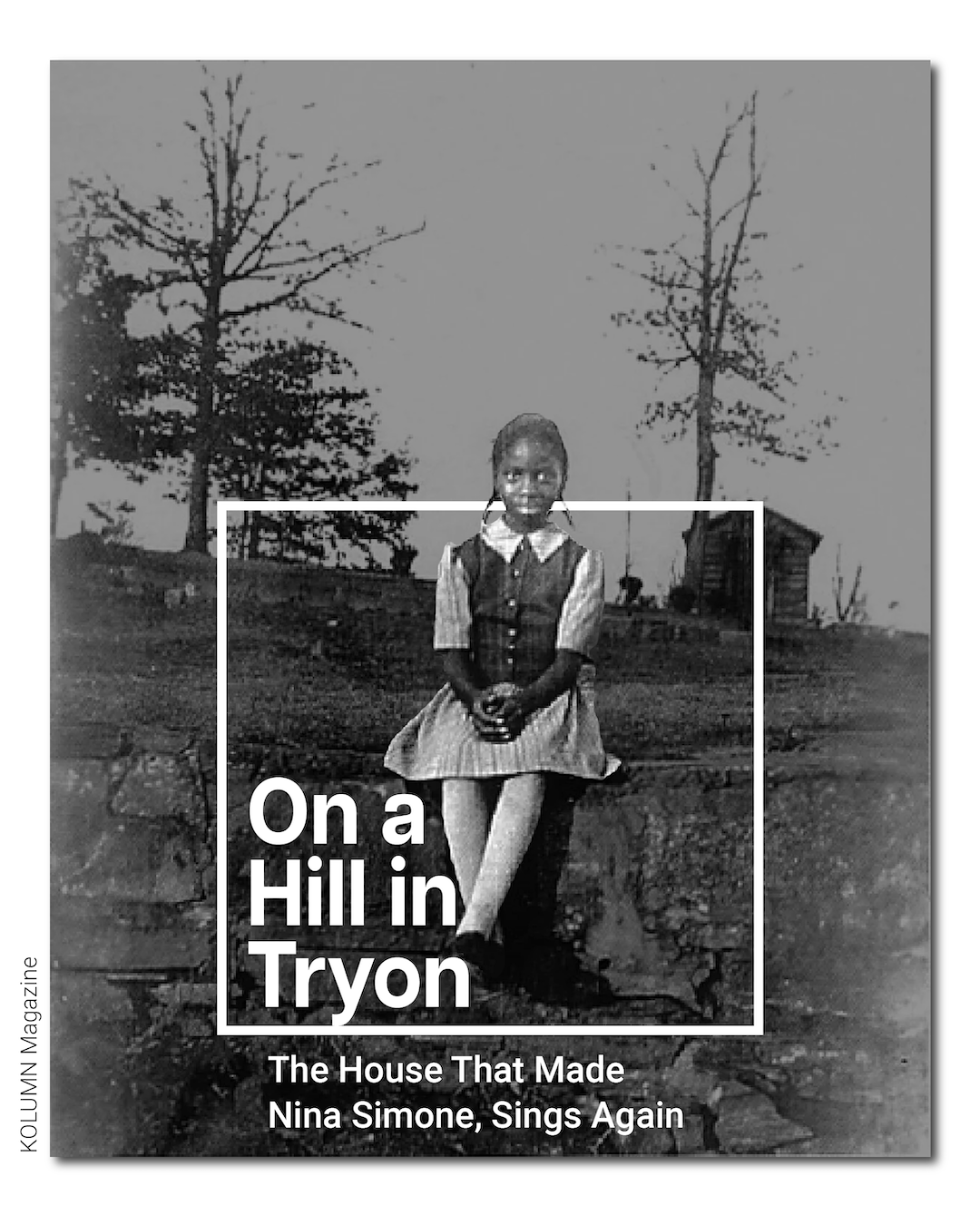

On a Hill

in Tryon

THE HOUSE THAT MADE

NINA SIMONE,

Sings Again

By KOLUMN Magazine

On a fall afternoon in Tryon, North Carolina, the little house where Nina Simone learned to play the piano looks almost impossibly modest.

It’s a 650-square-foot clapboard box perched on brick piers, three rooms deep, with a front porch now painted the pale “haint blue” long used across the South to ward off evil spirits. A century-old magnolia tree—locals know her as “Sweetie Mae”—still stands guard behind the house, its roots threading through the same soil that held the Waymon family’s laundry line and children’s games.

Until recently, the place was collapsing: a sagging roof, peeling paint, weeds tangling the steps that once carried a little girl named Eunice Kathleen Waymon from front porch to church pew and back again. Today, after a years-long, unlikely campaign involving New York artists, local elders, national preservationists, and a global fundraising effort that pulled in millions, the house has been carefully restored. Its tin shingles have been replicated, its pine floors refinished, its porch rebuilt to look much as it did when a three-year-old Eunice first climbed onto a battered upright piano and began to teach herself to play.

It is not yet open to the public, but this fall the African American Cultural Heritage Action Fund, a program of the National Trust for Historic Preservation, quietly announced that the rehabilitation of Nina Simone’s childhood home is complete. The plan is for it to become both an historic site and a space for artistic and community programming—a living archive of one Black girl’s genius and the world she remade with it.

“Restoring Nina Simone’s childhood home is about more than preservation—it’s an act of respect and imagination,” artist Adam Pendleton, one of the owners, said in a recent statement.

This is the story of how a forgotten house in a small Southern town became the focus of a global fight over what—and who—America chooses to remember.

Where Nina’s Story Begins

Eunice Kathleen Waymon was born in this house at 30 East Livingston Street on February 21, 1933, the sixth of eight children in a family where money was scarce but music and faith were abundant. Her mother, Mary Kate Irvin Waymon, was a Methodist preacher and domestic worker; her father, John Divine Waymon, was a barber, dry cleaner, and sometime entertainer.

The house itself is tiny: three rooms, roughly 650 square feet, set on a quarter-acre plot in Tryon’s historically Black East Side neighborhood. When you walk up the steps and through the front door, there is a main room that served as both living room and music room; a bedroom off to one side; and a rear room that functioned as kitchen and secondary sleeping space. Brent Leggs, the preservationist who would later help save the house, describes it as “a humble yet handsome three-room house…small, [but] the essence of what we’re preserving.”

Just a hundred yards from the front porch stands St. Luke CME Church, where Mary Kate preached and where Eunice—later Nina Simone—began her public life as a musician. By the age of three, she was picking out hymns on the family piano; by five, she was the church’s official pianist.

Tryon was a small town of about 1,700 people in the foothills of the Blue Ridge Mountains—a place where Black families lived with one foot in tight-knit community and the other in Jim Crow’s daily humiliations. At eleven, when Eunice played a classical recital at the local library to thank donors who’d contributed to a fund for her lessons, her parents were ordered out of their front-row seats to make room for white patrons. She refused to continue until they were returned to their place.

That moment—half family story, half origin myth—has long been read as a prelude to Simone’s later musical militancy in songs like “Mississippi Goddam” and “Four Women.” But in Tryon, the stories that cling to the house are more intimate: the sound of her father playing jazz standards at night, her mother’s voice lifting in the next-door church, siblings racing through the yard while Eunice practiced scales, dreaming of a future at the Curtis Institute of Music and a life as the first great Black classical pianist.

The Waymons left the house in 1937, when Eunice was still a small child. Over the decades, the building passed through various owners, was altered and patched, then ultimately left vacant. By the 1990s, it was in severe disrepair. Many people in Tryon drove past without realizing that the little weather-worn structure on the hill was the birthplace of a world-changing artist.

A Modest House, a Complicated Relationship

Nina Simone left Tryon as a teenager and, like many Black artists who fled the Jim Crow South, rarely looked back. Her relationship with her hometown was complicated, shadowed by the racism she experienced and by the thwarting of her dream to attend a major conservatory.

For much of the late 20th century, Tryon’s public memory of Simone lagged behind her global fame. It wasn’t until 2010 that a bronze statue of her was unveiled downtown, depicting the musician with her eyes closed, head lifted, fingers poised over an invisible keyboard.

That tension—between hometown pride and the legacy of exclusion—is woven into the very story of the house. In the early 2000s, a local economic development director bought the property and invested about $100,000 in an attempt to restore it as a historic site. Financial troubles derailed the project. By 2016, the house was back on the market, with demolition a very real possibility.

“It was vacant. It was deteriorating,” Leggs later recalled. “At first glance [it] might not seem to have a lot of meaning…But then you realize that Nina Simone was born here, that’s where she learned her art.”

Locally, some residents worried about being written out of their own story. In an essay about the preservation debate, writer Christiana Wayne notes that saving the house has forced Tryon to confront both its pride in Simone and the painful history that pushed her away.

Yet for others—especially Black elders who remembered walking past the Waymon home or hearing that little girl in church—the threat of losing the house felt like a second erasure. When preservationists and national media finally began to pay attention, they were arriving in the middle of a conversation Black Tryon had been having for years.

The Daydreamers Arrive

The turning point came at the end of 2016 with a simple email.

Laura Hoptman, a curator with ties to western North Carolina, wrote to New York–based artist Adam Pendleton to say that Nina Simone’s childhood home was for sale and in danger. Did he know anyone who might buy it—not as a speculative investment, but as a steward?

Pendleton mulled the message, then learned that fellow artist Rashid Johnson had received a similar note. “I had an aha moment,” he later recalled. “Wait a minute, we could purchase this house together. It could be a collective act, a collective gesture.”

He and Johnson approached two other celebrated Black artists, Ellen Gallagher and Julie Mehretu. In early 2017, the four formed an LLC—cheekily named Daydream Therapy—and bought the property for $95,000, sight unseen.

They made clear from the start that this was not a vanity project. As Johnson put it, the purchase was “an act of politics and arts activism,” a way for working artists to intervene directly in the fate of Black cultural heritage.

Their timing intersected with a larger shift. That same year, the National Trust for Historic Preservation launched its African American Cultural Heritage Action Fund, led by Brent Leggs, with a mission to save sites connected to Black history that had long been ignored by traditional preservation. Simone’s house quickly emerged as a priority.

In 2018, the Trust designated the home a “National Treasure,” one of fewer than 100 places in the United States to carry that title. Two years later, it secured a preservation easement through Preservation North Carolina—the strongest legal protection available, effectively ensuring that the house can never be demolished, only rehabilitated.

“What’s left in the house to connect to Nina Simone is the cultural legacy and memories that are embodied inside this simple, unadorned building,” Leggs said. “In many ways, it is the house itself…that we’re preserving.”

Raising the Money, Building a Movement

Saving a small wooden house in rural North Carolina turned out to require big-city capital and international attention.

The Action Fund and Daydream Therapy began with modest crowdfunding campaigns that drew support from everyday fans and high-profile admirers like Patti LaBelle and John Legend.

Then came the art world. In 2023, Pace Gallery and Sotheby’s hosted a charity auction of works donated by leading artists, co-hosted by tennis star Venus Williams. The event, along with related fundraising, ultimately pulled in nearly $6 million for the restoration and long-term endowment of the house.

“We didn’t even know what we were embarking on,” Pendleton told one gala crowd. “What we did know was the power of Nina Simone’s music, the power of an artistic legacy, the power of defining…what America is, and what America can be.”

Meanwhile, the HOPE Crew—a National Trust program that trains young people in hands-on preservation—arrived in Tryon. They scraped and repainted the exterior, stabilized the structure, and began cataloging which parts of the house could be saved and which would need careful replacement.

Local residents and church members were not merely spectators. The restoration team worked with Tryon’s East Side neighborhood, St. Luke CME Church, and Simone’s younger brother, Dr. Samuel Waymon, to shape a vision that centered the Black community that had raised her.

“Preserving our home preserves the piano lessons, the joy, the discipline, and the discovery of her gifted talent all recorded in those walls,” Waymon said. “It’s an honor to share this with the world as she would have wanted me to.”

A Restoration Rooted in Black Southern Life

The physical transformation of the house is striking, but it is also deliberately restrained.

Architects and preservationists worked to keep as much original material as possible—pine walls, floorboards, fragments of 1930s linoleum—while making the building safe and accessible for future visitors. Stamped tin shingles were recreated for the roof. Inside, the rooms have been fitted out with furnishings that match the period and the Waymons’ economic reality rather than indulging in glossy fantasy.

Outside, the team restored a traditional “swept yard,” a packed dirt lawn once common across the rural South, and outlined the foundations of a former work shed and outhouse uncovered by archaeologists. The towering magnolia behind the house, likely close to 100 years old, was carefully protected throughout construction.

Crucially, modern systems—geothermal heating and cooling, a fire-suppression system, and an ADA-compliant ramp—have been woven in discreetly, respecting both Simone’s legacy and the need for the site to welcome visitors of all abilities.

The aim, Action Fund staff have said, is not to create a frozen shrine but an “inspired archive” of Simone’s early life and the Black Tryon community that nurtured her.

“Preservation is an expression of what we choose to honor,” Leggs said as the restoration wrapped. “The restoration of her home affirms her rightful place in the American story—one defined by brilliance, resilience, and the power of art to shape our collective conscience.”

What Comes Next

For now, the restored house remains closed as its stewards plan the next phase: programming.

Behind the scenes, Daydream Therapy, the Action Fund, and local partners are sketching out a future that could include artist residencies, small performances, educational visits, and collaborations with Tryon schools and churches. The house is too small to handle heavy tourist traffic; the challenge is to build a sustainable model of “ethical cultural tourism” that benefits the Black community around it rather than displacing it.

There are unresolved tensions. Simone’s complicated feelings about her hometown still hover over Tryon, as do questions about how a global icon’s birthplace can be both a local landmark and an international destination. Some residents worry about rising property values and the possibility that the very neighborhood that nurtured Simone could be priced out of its own history.

At the same time, there is a sense that what happens in this little house may help reshape American preservation more broadly. Black homes and neighborhoods, especially modest ones, have often been deemed unworthy of saving; their buildings are too small, too altered, too ordinary for the traditional canon of “heritage.” In centering a three-room pier-and-beam house in Tryon, Leggs argues, preservationists and artists alike are insisting that the roots of Black genius are themselves worthy of monumental care.

The Power of a Small House

It is easy, standing on the restored porch and looking out toward St. Luke CME Church, to imagine a little girl watching her mother preach, then hurrying back up the hill to practice at the piano. The distance between those two doors—sanctuary and home—is barely a hundred yards. The distance her music would ultimately travel is immeasurable.

Pendleton has described his first visit to the house as a kind of revelation. “Everything begins somewhere,” he said. “And this is where it began for her.”

The genius of the Nina Simone Childhood Home project is that it takes that “somewhere” seriously—not as a footnote, but as a central text. It asks us to see the beauty and power in a humble Black Southern house, and to recognize that the stories born in such places are not sidebars to American history. They are American history.

The girl who refused to play until her parents were allowed to sit in the front row grew up to write soundtracks for a movement that challenged the very foundations of that America. The house that raised her is still small. But, as the magnolia behind it quietly testifies, its roots run deep, and their reach is only growing.