Pennies, Passbooks, and Protest

HOW BLACK AMERICANS Turned Their Banks Into Engines of Freedom

By KOLUMN Magazine

A few years ago in Washington, D.C., construction workers pulled up a floorboard in an old row house and found a cache of 935 silver coins.

In court, the family explained why the money had been buried more than a century earlier: John Johnson, a vegetable seller, had lost his savings when the Freedman’s Savings Bank collapsed in 1874. He never trusted a bank again, but he kept saving, tucking his wealth into the floor rather than back into an institution that had failed him.

Johnson’s hidden coins are more than an eccentric family story. They’re a symbol of the uneasy relationship between Black Americans and the U.S. banking system — a relationship in which African American–owned banks have often served as both refuge and battleground.

From the ruined ledgers of Freedman’s Bank to the glossy apps of today’s #BankBlack movement, millions of Black depositors have tried, again and again, to build security in institutions they could call their own. Their stories trace a different kind of financial history: not just interest rates and capital ratios, but the emotional stakes of putting your name on an account in a country that has never fully trusted you back.

THE FIRST PROMISE: FREEDMAN’S SAVINGS BANK

In March 1865, as the Civil War staggered to a close, Congress created the Freedman’s Savings and Trust Company. For newly emancipated people with little more than their labor and army pay, the bank appeared to be a bridge into freedom’s next chapter. Within seven years it had opened 37 branches in 17 states and D.C., gathering deposits from more than 67,000 account holders and holding over $3.7 million — roughly $80 million in today’s dollars.

The surviving passbooks and signature registers read like a roll call of Reconstruction: formerly enslaved laborers, Black Union soldiers, washerwomen, carpenters, teachers. The records, now searchable at the National Archives, capture not just balances but family ties — names of spouses, children and employers — making them some of the most detailed documents about the first generation out of slavery.

Depositors walked into Freedman’s marble-front buildings believing the institution was backed by the federal government. Advertisements and speeches by white trustees and prominent supporters like Frederick Douglass helped reinforce that perception of safety.

But the guarantee was an illusion. Mismanagement, speculative loans by white officers and weak oversight hollowed out the bank. Despite Douglass’s late, desperate attempt to shore up the institution with $10,000 of his own money, Freedman’s failed in 1874. Many depositors received only a fraction of what they had saved; some, reluctant to mail their precious passbooks to Washington, received nothing at all.

For people like John Johnson, the failure was more than a financial loss; it was a betrayal of a fragile new trust. Historians and contemporary observers alike have argued that the collapse left a “gaping hole” in Black wealth and seeded a generational distrust of banks — a shadow that would hang over every Black-owned institution that followed.

“WE WILL START A BANK”: TRUE REFORMERS AND MAGGIE WALKER

If Freedman’s was a broken promise, the first generation of Black-owned banks was a declaration of self-reliance.

In Richmond, Virginia, Rev. William Washington Browne — a former enslaved man and Civil War veteran — led a fraternal society called the Grand Fountain United Order of True Reformers. Shut out of white-controlled institutions and scrutinized whenever the group tried to handle money, Browne and his colleagues decided to start their own bank so their finances would no longer be subject to white suspicion.

Chartered in 1888, the True Reformers Savings Bank opened in 1889 and grew from a desk in Browne’s home into a million-dollar institution that survived the Panic of 1893. Customers deposited wages from domestic work, railroad jobs and small businesses, proud to see their money held and managed by Black professionals.

But mismanagement, embezzlement and unsecured loans eventually toppled True Reformers in 1910, wiping out many depositors’ savings. It was another painful lesson: even a Black-owned bank was not immune from the broader risks of a racist, lightly regulated financial system — and when it failed, Black depositors rarely got a second chance somewhere else.

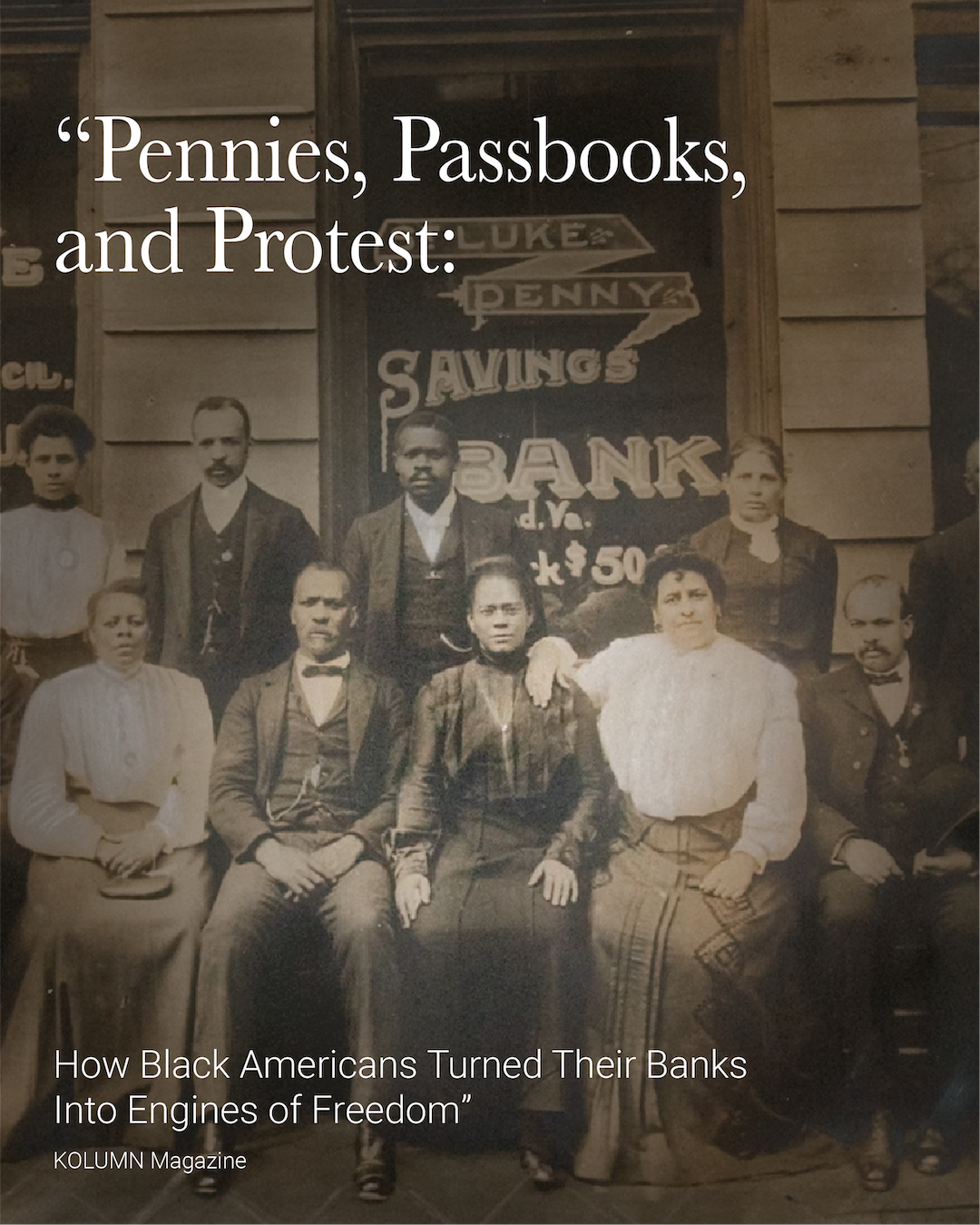

That same city would produce one of the most successful and enduring models of Black banking: Maggie Lena Walker’s St. Luke Penny Savings Bank.

Walker, a former laundress and the daughter of a woman who’d been enslaved, led the Independent Order of St. Luke, a Black women’s benevolent society. In 1903, she founded St. Luke Penny Savings Bank, becoming the first woman of any race in the U.S. to charter and run a bank.

For Walker’s customers — many of them Black women — the bank was an antidote to the indignities of cash-only life. Members brought in “pennies, nickels and dimes” from domestic work and small enterprises, often in the same halls where they held mutual-aid meetings and funerals. By 1920, St. Luke had issued more than 600 mortgages to Black families in Richmond, helping transform renters into homeowners and clerks into business owners.

A century later, historians of St. Luke describe how those early customers treated the bank as an extension of their social world: a place where the teller might also be a neighbor or lodge sister, where the loan officer understood that a missed payment could be the difference between a child’s school fees and an eviction notice.

The small-scale intimacy of these relationships is a recurring theme in the history of Black banking. For customers who met discrimination and contempt at white institutions — or no service at all — Black banks were not abstractions. They were rooms full of familiar faces, one of the few places where “customer” and “citizen” could feel like the same thing.

MIGRATION MONEY: BANKS OF THE BLACK BELT AND BEYOND

As the Great Migration sent millions of Black Southerners north and west between 1910 and 1970, their money followed. Depositors carried cash in envelopes and handbags, sometimes sewn into hems, looking for banks that would treat them as more than a risk.

Chicago’s Jesse Binga was one of the men who tried to meet them where they landed. Arriving in the city in 1892 with $10 in his pocket, he built a real estate empire and, in 1908, founded Binga State Bank in the heart of Chicago’s Black Belt.

For Black migrants facing hostile white bankers and racially restrictive covenants, Binga’s institution was both a lender and a form of protection. Customers opened accounts to buy two-flats, finance barber shops and insure themselves against the volatility of factory work. The bank’s success made Binga a symbol of Black prosperity — and a target. His buildings were attacked during the 1919 Chicago race riot; the bank would later fail during the Great Depression after it was denied support from a white banking association, even as other institutions were rescued.

Across the country, Black banks and thrifts carved out similar roles. In Atlanta, Citizens Trust Bank, founded in 1921, became a cornerstone for Black homeowners and businesses. Decades later, investigative work on “the color of money” in Atlanta found that only two Black-owned institutions — Citizens Trust and Mutual Federal Savings and Loan — made more home loans in Black neighborhoods than in white ones, in stark contrast to mainstream banks’ lending patterns.

For the customers of these institutions, the numbers translated into something simple but profound: the ability to get a mortgage at all; a car loan that wasn’t predatory; a place to deposit the week’s pay without being charged punitive fees or treated as a suspect.

REDLINING, RESISTANCE AND THE COST OF BEING “BANKED”

Even as Black-owned banks expanded, they operated inside a system bent against their customers.

Through the mid-20th century, federal housing policy and private redlining restricted Black borrowers to certain neighborhoods, starved them of mainstream credit and inflated the costs of borrowing. Research today still finds that majority-Black areas tend to have fewer bank branches, less access to credit and higher interest rates on business loans than comparable white communities.

In that context, being “banked” did not always mean being fully included. Studies of modern financial behavior show that Black families with bank accounts are significantly more likely than white families to rely on nonbank services — check cashers, payday lenders, pawn shops — to fill gaps left by mainstream banks.

For many Black customers, the choice to use a Black-owned bank has never been purely about price or convenience. It’s a way of reclaiming some control in a landscape where they are more likely to be denied loans, charged higher fees or steered into inferior products — and where the consequences of rejection can echo across generations.

CRISIS, CONSOLIDATION AND THE SHRINKING MAP

The late 20th and early 21st centuries were brutal to community banks, and Black-owned banks were hit especially hard.

Between 2001 and 2020, the number of Black-owned banks dropped from 48 to just 20, even as the overall U.S. banking sector remained vast. Large recessions tended to wipe out a disproportionate share of minority institutions: when economic storms came, Black banks, with smaller capital cushions and riskier customer bases by necessity, went under at higher rates.

Yet the customers who stuck with these banks often found them to be stubborn lifelines. An Investopedia analysis noted that during the 2007-08 financial crisis, even as overall mortgage lending to Black borrowers fell 69 percent, the number of mortgages originated by Black-owned banks actually rose by 57 percent.

That willingness to lend in tough times deepened many customers’ loyalty. But it also meant that the institutions most committed to Black communities absorbed more of the risk that other banks shunned — another way in which Black depositors and borrowers shouldered the costs of a crisis they did not cause.

#BANKBLACK: PROTEST BY DEPOSIT SLIP

In July 2016, after police killings of Alton Sterling and Philando Castile, Atlanta rapper and activist Michael “Killer Mike” Render stood up at a town hall and issued a challenge: if one million people opened a $100 account at a Black-owned bank, that would move $100 million into Black-controlled institutions.

Within days, about 8,000 people opened accounts at Citizens Trust Bank in Atlanta. The #BankBlack hashtag spread across social media, turning bank branches and online sign-up pages into extensions of the street protests.

Customers described the decision in pointedly political terms: they were tired of watching major banks foreclose on Black neighborhoods while financing private prisons or donating to politicians who backed voter suppression. Moving their money, they said, felt like a tangible way to protest — and to build.

Four years later, after the murder of George Floyd in Minneapolis, the movement surged again. OneUnited Bank, the largest Black-owned bank in the U.S., reported that it had surpassed 100,000 customers and credited the growth to a combination of social-justice activism and a digital platform that allowed customers to open accounts from their phones.

At the same time, big banks and corporations pledged billions of dollars in racial-equity commitments, including deposits and investments into minority depository institutions and community development financial institutions. Some of that money has since reached Black banks’ balance sheets, boosting their capital.

Robert E. James II, chair of the National Bankers Association, says those injections mean that Black-owned banks — just 22 out of 4,645 banks as of late 2023 — are “stronger than at any time since the 1980s,” with more than $1 billion in new permanent capital that could translate into roughly $10 billion in new lending.

For the customers who opened accounts during the #BankBlack waves, the question now is whether that capital will show up in their lives as lower-cost loans, expanded branches and more patient support for small businesses — or remain an abstract line in institutional reports.

NEW BANKS, NEW APPS, OLD QUESTIONS

The post-Floyd era has also seen the rise of fintechs targeting Black and Latino consumers — and a debate over what truly counts as “banking Black.”

In 2020, a digital platform called Greenwood, backed by Killer Mike and other high-profile founders, announced plans to offer debit cards and financial services marketed specifically to Black and Latino customers. Major banks and investors poured tens of millions into the company, which promised a kind of 21st-century analogue to the institutions built by Maggie Walker and Jesse Binga.

Customers signed up in large numbers, often driven by the same impulse that had guided earlier #BankBlack efforts — a desire to see their deposits aligned with their values. But as The Washington Post later reported, Greenwood struggled to meet some of its initial goals, drawing criticism from customers and advocates who questioned fees, app performance and the company’s decision to expand into lifestyle and media acquisitions rather than core banking.

Leaders of traditional Black-owned banks pushed back against coverage that lumped them together with nonbank fintechs. In a 2024 response, the National Bankers Association argued that while some tech platforms market themselves as “for the culture,” only regulated banks — many with histories stretching back a century — have consistently provided mortgages, small-business credit and paycheck accounts in communities mainstream banks ignore.

At the same time, new brick-and-mortar Black banks are still being born. In Columbus, Ohio, Adelphi Bank opened in 2023 as the state’s only active Black-owned bank, launched by local leaders who’d been pepper-sprayed while protesting George Floyd’s killing and decided to turn that moment into a long-term financial institution.

In 2024, Redemption Holding Co. acquired a Utah institution to create Redemption Bank, the first Black-owned bank in the Rocky Mountain region and one of the few located outside a historically Black or economically distressed community. With civil-rights leader Bernice King on its advisory board, Redemption plans to focus on commercial and small-business lending while building a national digital platform.

For customers walking into Adelphi’s branch in Columbus’s historic King-Lincoln Bronzeville neighborhood or logging into Redemption’s app from another state, the pitch is familiar: this is a bank that understands your story and will use your deposits to unlock opportunity in places others have abandoned.

WHAT BLACK BANK CUSTOMERS SAY THEY WANT

If you scroll through #BankBlack posts or attend community banking forums, certain themes recur in how Black customers talk about their money.

They want dignity at the counter — not to be second-guessed about their checks or their balances. They want a loan officer who doesn’t assume default when they see a Black surname or a ZIP code. They want their deposits recycled into mortgages for their neighbors, lines of credit for local barbershops and capital for child-care centers and small landlords trying to keep rents stable.

They also want modern tools: surcharge-free ATMs, mobile deposit, budgeting apps, transparent fees. OneUnited, for example, has built a network of tens of thousands of ATM and cash-reload locations to serve customers who may not live near a traditional branch.

Underneath those requests is a deeper demand: that the simple act of being a bank customer not require a compromise of safety or self-respect. Recent studies show that Black borrowers continue to face higher loan denial rates and pay more for credit than white borrowers with similar profiles, while majority-Black communities see less small-business lending overall.

Black-owned banks cannot erase that entire landscape on their own. But for many of their customers, these institutions are the only ones that have ever tried.

THE LIMITS — AND POWER — OF BANKING BLACK

Economists who study the sector are clear: Black-owned banks, by themselves, cannot close the racial wealth gap. Their collective assets are measured in billions, compared with the trillions controlled by the largest U.S. banks. Structural inequities in housing, education, labor markets and tax policy all shape the gap in ways no community bank can fix alone.

Yet research also suggests that minority-owned banks, including Black institutions, play an outsized role in making communities more resilient. A Federal Reserve paper found that minority banks help cushion local employment during downturns, not just for minority residents but for non-minority workers as well, by maintaining credit flows when other lenders pull back.

For the customers whose stories run through this history, that resilience is not an abstract metric. It looks like a bank that keeps a small-business line of credit open during a pandemic, instead of cancelling it at the first sign of stress. It looks like a mortgage officer who structures a loan around the irregular income of a gig worker, rather than denying the application outright.

It also looks like a teenager watching a parent deposit cash not into a check-cashing outlet but into an account that pays interest and comes with a debit card, a credit-building product and a banker who will answer their questions without condescension.

Robert James of the National Bankers Association likes to frame the work in terms of opportunity multiplied: every new dollar of capital, he notes, can support roughly ten dollars of loans. The hope, for depositors, is that those multiples show up on their own blocks — in the form of renovated homes, staffed-up clinics, repaired roofs at daycares and churches.

FROM PASSBOOKS TO PUSH NOTIFICATIONS

Almost 160 years after Freedman’s Savings Bank opened its doors, Black Americans still face a fundamental question each time they walk into a branch or download a banking app:

Can this institution be trusted with more than my money? Can it be trusted with my future?

The long arc of African American banking is, at its core, a story told by customers.

By the freedpeople who lined up to sign their names in Freedman’s ledgers, believing that savings accounts were the next step after emancipation — and by those who buried coins in floorboards when that faith was betrayed.

By the mothers in Richmond who walked into Maggie Walker’s bank with coins wrapped in handkerchiefs and walked out with mortgages in their own names.

By the Great Migration families who stood in line at Binga State Bank or Citizens Trust, clutching documents that would, for the first time, make them owners rather than boarders.

By the protesters who, instead of burning their cities, opened accounts in 2016 and 2020, using their routing numbers as instruments of protest and hope.

And now by the customers of new banks in Columbus, Salt Lake City and beyond, who see these places not just as financial institutions but as arguments that Black prosperity belongs everywhere in the American landscape, not just in a few carved-out enclaves.

John Johnson’s descendants eventually got to claim their ancestor’s buried coins. They were a reminder of what had been stolen — and of his refusal to stop trying to save.

Black-owned banks, in their imperfect, hard-won way, are the institutional version of that refusal. Every account opened, every loan underwritten, every branch kept alive in a neighborhood others have written off, is a quiet assertion that Black people are not just subjects of financial policy, but authors of their own economic stories.