A story about technique, distribution, and who gets remembered.

A story about technique, distribution, and who gets remembered.

By KOLUMN Magazine

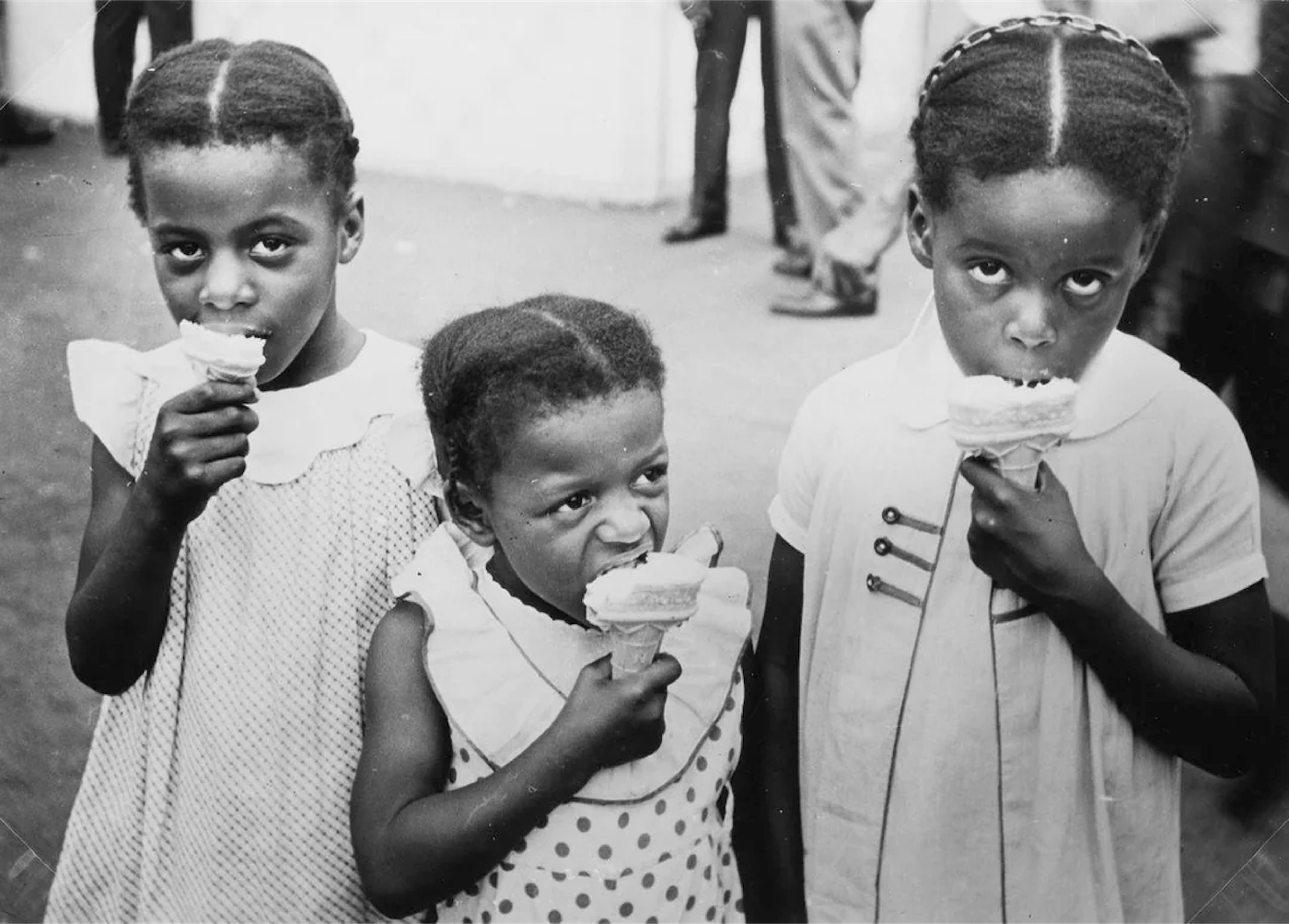

America is an invention-obsessed country, and dessert is one of its favorite stages for origin myths. We want a single person, a single moment, a clean “before” and “after.” Ice cream resists that impulse. It is older than the United States; it traveled across continents as ideas and ingredients do; it shows up in cookbooks and diaries and advertisements as a social signal long before it becomes a supermarket staple.

Yet one name has increasingly been asked to carry an especially American kind of meaning: Augustus Jackson, a free Black Philadelphian in the early 19th century, often described as the “Father of Ice Cream.” The title is arresting—and, on the strictest terms, unstable. Even sources that celebrate Jackson typically acknowledge he did not invent ice cream itself. The more responsible claim is narrower: that he helped modernize the method of making it, improving the process in ways that made production more consistent and distribution more feasible in his time.

That distinction matters, because the Jackson story sits at a crossroads where American history repeatedly misleads readers: where the hunger for heroic origin tales collides with the reality of incremental innovation, and where Black contributions are praised in viral retellings but poorly documented in the institutional record that confers permanence. The result is a biography that can feel both overconfident and under-sourced at once—too certain about details that can’t be verified, too casual about the mechanisms that erased the paper trail in the first place.

To write about Augustus Jackson with integrity is to hold two ideas in the same hand without dropping either. The first is that ice cream, as a technique, predates him by centuries; that the use of salt and ice to depress freezing temperature is not a secret discovered in the White House kitchen; and that many steps in the ice cream timeline have other names attached to them—some famous, some obscure, many uncredited.

The second is that Jackson’s significance does not need the false precision of “inventor” to be real. In a pre-electric world—where “cold” had to be harvested, purchased, stored, transported, and defended against time—anyone who could make frozen desserts reliably, at scale, for sale, was solving an industrial problem. That is the heart of manufacturing innovation: repeatability under constraints. And in the story that can be supported across multiple sources, Jackson appears not merely as a talented cook, but as an operator: someone thinking about process control, product consistency, packaging, and distribution in a city with an appetite and a growing commercial infrastructure.

Before “innovation,”

there was ice

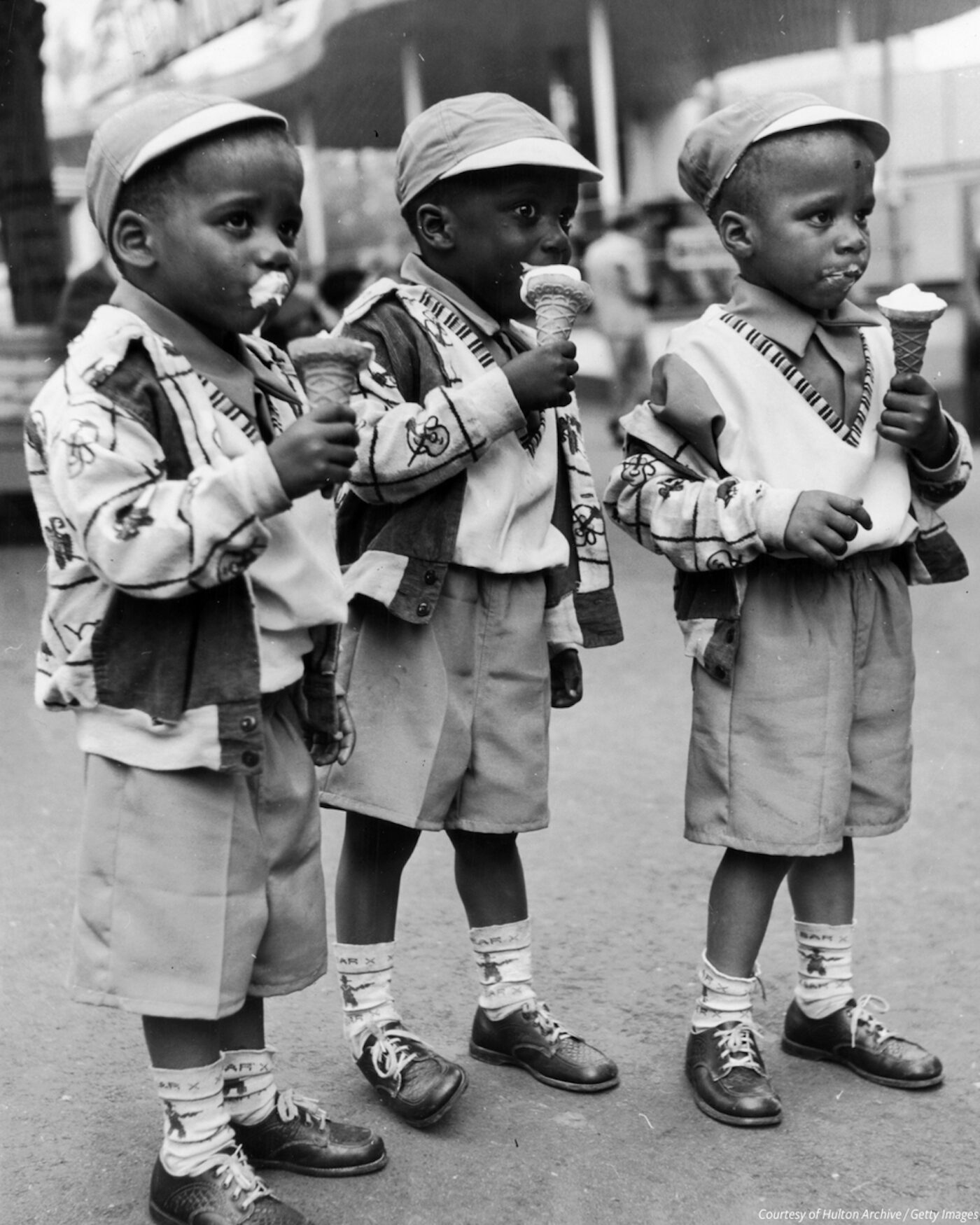

In the era Jackson lived in, the dessert was less important than the cold chain. Ice cream is a fragile thing even now; it is practically rebellious in the early 1800s. Without electric refrigeration, cold had to be mined in winter and preserved. Cities like Philadelphia and New York became hubs in a broader ice economy that turned frozen water into an urban commodity. It is hard to understand any “ice cream pioneer” without first seeing the scaffolding beneath the cone: icehouses, insulated storage, delivery routes, laborers hauling blocks, and customers wealthy enough to pay for a pleasure that literally disappeared into air if mishandled.

The technology of freezing in this period often relied on a principle now taught in school science labs: mixing salt with ice lowers the mixture’s freezing point, allowing temperatures below 32°F and creating the conditions to freeze a custard base more quickly and evenly. This was not an American discovery. The general method appears in older European culinary writing, and modern fact-checking treatments of the Jackson legend emphasize that “salt-and-ice” was known well before his supposed innovations.

So why does Jackson keep returning to the narrative? Because innovation is not only about firsts; it is about adoption. A technique can exist for a century as knowledge among elites, or as a trick scattered through cookbooks, before someone adapts it to the messy realities of business—time, labor, cost, and customer demand. A manufacturing innovation might be less about discovering a phenomenon than about standardizing it, making it teachable, making it profitable, and making it repeatable beyond a single kitchen.

A free Black cook in an early American power kitchen

Several modern summaries of Augustus Jackson’s life share the same basic arc: born in Philadelphia in 1808, he later worked in the White House kitchens, then returned to Philadelphia to run a confectionery and ice cream business, developing flavors and a method of manufacture that others would emulate.

The White House detail is central to the legend because it implies proximity to elite taste and access to demanding diners whose expectations could push a cook toward more refined technique. Library of Congress blog material places Jackson working in the White House during James Monroe’s presidency in the 1820s, then leaving and starting a catering business.

But here is where a journalist has to slow down. In the popular retellings, Jackson’s White House years often stretch into neat round numbers and multiple administrations, delivered with a confidence that the broader documentation does not always match. The best approach is not to deny the claim, but to treat it as a plausible framework rather than a proven ledger. Even sympathetic writing about Jackson acknowledges the record is thin; the Philadelphia Inquirer’s reporting is explicit about the scarcity of historical mentions and the difficulty of pinning down details.

That scarcity is not incidental. Food work—especially the food work performed by Black Americans in service roles—has historically been treated as background labor, the kind of indispensable skill that produces comfort and prestige for others while leaving little trace of its own authorship. Adrian Miller’s work on African Americans in presidential food service argues, in effect, that the kitchen has always been part of the political machine, even when its workers were treated as invisible. A chapter associated with Miller’s scholarship underscores that whatever the competing origin claims, Jackson did know how to make an eggless ice cream and used that knowledge in business.

Whether or not every White House detail can be verified to the satisfaction of an archivist, the broader point survives scrutiny: Jackson’s story belongs to a tradition of Black culinary skill being refined in spaces of power and then redeployed for entrepreneurship—often in Black urban communities where markets existed but recognition did not follow.

What, exactly, did Augustus Jackson “innovate”?

The most frequently repeated claims about Jackson’s ice cream manufacturing innovation fall into three buckets.

The first is process control: he “invented a method for controlling the freezing of custard,” as one Library of Congress post puts it, suggesting a technique for managing texture and consistency rather than merely following a recipe.

The second is formula: multiple sources claim he developed an eggless recipe at a time when many ice cream recipes were egg-based, a shift that would change mouthfeel, cost, and possibly shelf stability—an important consideration for commercial distribution.

The third is distribution and packaging: he sold ice cream in metal tins (or tin cans) and supplied other vendors or parlors, indicating a business model that treated ice cream not only as a dish served directly to diners but as a product that could be packaged, transported, and resold.

On their own, none of these claims automatically make Jackson the singular “father” of anything. But together they describe something that looks like modern food manufacturing: a deliberate focus on repeatability and a product pathway beyond the point of production.

This is where the Jackson story becomes more credible, because it aligns with what we know about the period’s commercializing impulses. Philadelphia had a vibrant culture of confectionery and street vending, including Black vendors and entrepreneurs; the Historical Society of Pennsylvania’s writing on the city’s ice cream history places Jackson among innovators who helped broaden access, and it explicitly frames the story as a mix of inventors, distribution methods, and later food safety improvements.

If you are trying to understand “manufacturing innovation” in a pre-industrial context, the tin can matters as much as the flavor. It suggests portioning and batch standardization. It implies inventory. It implies that the “unit” of ice cream could be counted, priced, and moved. It hints at relationships with other sellers, meaning Jackson may have been more wholesaler than mere shopkeeper at times. It also implies a need for the cold chain: once you package a product to travel, you have to engineer time itself—how long until melt, how to keep texture, how to keep a lid sealed, how to stage deliveries when the day warms.

In other words, the innovation might not be a single “secret step,” but an operational system.

The salt claim: Familiar, important, and often overstated

No element of the Augustus Jackson legend travels faster online than the rock salt detail. The story is usually told like this: Jackson added salt to ice while churning, enabling the mixture to reach lower temperatures and freeze properly. This, the story says, is the method still used in traditional churners today.

The chemistry is real. The historical exclusivity is not. Modern skeptical examinations stress that salt-and-ice freezing was known long before Jackson, and even Wikipedia’s synthesis of sources notes that mentions of salt and ice appear as early as the early 1700s in English culinary writing.

So why keep the salt detail at all? Because the point may not be discovery; it may be application at scale. The same skeptical writing that disputes Jackson as “inventor” still leaves room for him as a popularizer or improver—someone who used the method in a commercial setting and taught or influenced others through practice, not patents.

This is a familiar pattern in the history of food technology. Techniques circulate informally. They move through apprenticeships, through community knowledge, through the migration of workers, through observation and imitation. If Jackson found a way to make the salt-ice method reliable in Philadelphia’s commercial environment—if he refined ratios, standardized churning times, or improved batch handling—that could have constituted innovation even if the underlying thermodynamics were centuries old.

The tragedy for historians is that such innovation often leaves no paper. Jackson, according to multiple accounts, did not patent his method. Without patents, recipe manuscripts, or business ledgers preserved in archives, the story becomes dependent on later newspaper features, community memory, and secondary retellings—exactly the kind of sources that can inflate legend while losing specifics.

The eggless angle: A manufacturing choice hiding inside a recipe

The eggless-ice-cream claim is more intriguing than it first appears. In popular food culture, eggs are a taste preference—custard versus “Philadelphia-style,” richness versus lightness. In commercial practice, eggs are also a cost and a complication. They are an ingredient with supply variability and a spoilage profile; they require careful handling. If Jackson did in fact develop an eggless base that still delivered desirable texture, he would have been optimizing for production realities as much as flavor.

BlackPast’s biography of Jackson highlights that most early ice cream recipes used eggs and that Jackson devised an eggless recipe, alongside claims about adding salt to ice and selling ice cream in metal tins.

A chapter connected to Adrian Miller’s work similarly treats Jackson’s eggless knowledge as a real element amid competing origin claims, emphasizing that Jackson used it to run a confectionary business.

If we take these points seriously, Jackson’s “innovation” begins to look less like a single dramatic invention and more like a set of production choices: reduce complexity, increase consistency, make the product easier to produce repeatedly, and make it more resilient in a distribution context.

This is exactly the kind of innovation that builds industries. It is also the kind that is easiest to undervalue in hindsight, because it lacks the drama of a patent drawing or a breakthrough machine.

Philadelphia as a proving ground: Black confectioners and the business of pleasure

Any credible account of Jackson’s impact has to place him inside Philadelphia’s specific ecosystem. The city had a bustling commercial food scene and a population that could support specialty sweets. It also had Black entrepreneurship in food trades, even under the heavy constraints of racism and the broader national conflict over slavery.

The Philadelphia Inquirer’s column on Jackson is useful not because it confirms every claim, but because it stages the central journalistic question: where did the “Father of Ice Cream” story come from, how did it travel, and what sources can be shown? The column cites language from later reporting that described Jackson as “known in his day and time as ‘the man who invented ice cream,’” and it acknowledges how fragile such claims become when they are hard to corroborate with contemporaneous documentation.

The Historical Society of Pennsylvania’s material adds texture by framing Jackson among multiple actors who shaped Philadelphia’s ice cream accessibility, emphasizing both innovation and distribution.

Taken together, these sources suggest a reasonable thesis: Jackson mattered because he operated in a city where the market, the logistics of ice, and the culture of confectionery could reward someone who treated ice cream as a product rather than an occasional spectacle.

And that product orientation, in turn, points back to Jackson’s alleged packaging and wholesaling. If he supplied parlors, he participated in the multiplication of the dessert: a single producer enabling many sellers, a proto-supply-chain model. That is a different kind of influence than being a beloved local vendor. It is influence through replication.

Innovation as labor: What it means that the method wasn’t patented

The absence of a patent in the Jackson story is usually mentioned as a regrettable footnote—if only he had patented it, the legend suggests, he would be universally recognized. But patents are not merely paperwork; they are part of a system that presumes access to legal infrastructure, capital, and social legitimacy. Many working craftspeople never patented their methods, and many marginalized people had even fewer incentives and fewer pathways to do so.

If Jackson’s innovations circulated through practice—through recipes spoken aloud, methods observed in a kitchen, techniques taught to assistants or copied by competitors—then his work could shape an industry while remaining formally unclaimed. That is not a failure of Jackson alone; it is a description of how knowledge often moves in food culture.

And it leads to a deeper point about manufacturing innovation. Some innovations are “owned” because they are machine-based and capital-intensive: churns, freezers, refrigeration technologies. Others are embodied: timing, ratio, temperature judgment, batch handling. Embodied innovation is less likely to be preserved as a document, more likely to be preserved as a tradition—until the tradition itself is flattened into “people used to do it this way” without a name attached.

Why Jackson’s story still matters to how we think about American food

If Augustus Jackson were only a contested figure in an obscure dessert history debate, his story would be a footnote. He matters because the debate around him is a case study in American memory.

First, it forces us to rethink what counts as innovation. In modern tech culture, innovation is coded as patents, founders, and venture capital. Jackson’s likely contribution—process improvements, product consistency, packaging, distribution—looks less like a lightning bolt and more like operations. But operations are what scale a culture. Operations are what turn a novelty into a habit. If Jackson helped Philadelphians buy ice cream more often, in more places, with more predictable quality, then he was innovating in the most consequential sense: he was changing behavior.

Second, it highlights Black entrepreneurship in a period too often told through the narrow lens of abolition politics alone. A free Black confectioner building wealth in the 1830s and 1840s complicates the way Americans imagine the economic lives available to Black citizens—even as racism and exclusion remained structural facts. That complexity is not a feel-good add-on; it is central to understanding how Black communities built institutions and economies despite hostile conditions.

Third, it warns against the genre of “hidden figure” storytelling when it becomes a substitute for archival work. There is a difference between recovering a neglected life and manufacturing certainty where the record is ambiguous. The Jackson story, told carefully, can do the former without falling into the latter.

A more honest way to tell the Augustus Jackson story

A responsible version of the Augustus Jackson narrative sounds less like a viral post and more like a reported feature with humility.

It begins in Philadelphia, where Jackson is born in 1808, a free Black man in a city that is both a cradle of abolitionist activity and a marketplace with its own hierarchies. It follows him, plausibly, into elite kitchens—possibly the White House—where the discipline of service demands repeatable excellence. It brings him back to Philadelphia with skills sharpened and ambitions intact. He enters the confectionery trade at a moment when ice cream is still a luxury, but one increasingly available through urban ice storage and the growth of commercial sweets. He develops flavors, experiments with base formulas, and uses freezing techniques to improve consistency. He packages ice cream in tins, making it portable enough to sell through channels beyond a single storefront. He becomes, at minimum, a significant local manufacturer and supplier, part of the city’s wider story of Black food entrepreneurship.

Then the record fades. Jackson dies in 1852, according to multiple reference accounts, and what survives is less a dossier than a drift of mentions. Later newspapers and compilers resurrect him, sometimes as “the man who invented ice cream,” sometimes as “father of modern ice cream,” sometimes as a White House chef whose technique lives on in hand-crank churners. The more the story travels, the more it simplifies, until it becomes a single declarative sentence.

The journalist’s job is not to repeat the simplest sentence. It is to explain how it formed—and to offer a truer sentence in its place.

A truer sentence might be this: Augustus Jackson represents a kind of American innovation that rarely gets framed as innovation at all—Black culinary labor turned entrepreneurial method, adapted to a pre-refrigeration economy, preserved unevenly by institutions that did not prioritize Black authorship, and later revived in the language of “firsts” because that is the language the country uses when it finally decides someone mattered.

The significance of a sweet, melting legacy

In the end, the power of the Augustus Jackson story is not that it offers a clean answer to “who invented ice cream?” It doesn’t, and it shouldn’t pretend to. Ice cream is a long, transnational history of ingredients, techniques, machines, and markets.

The power is that Jackson’s legend—fact braided with folklore—forces a confrontation with how American food becomes American culture. It forces us to see the industrial challenge hidden inside a pleasure. It forces us to see a city’s Black entrepreneurs not as background characters but as producers of taste. It forces us to ask what other manufacturing innovations were performed in kitchens and workshops, transmitted through hands rather than documents, and then lost when the nation decided whose work was worth filing away.

And if you are publishing this story for a contemporary audience—KOLUMN’s audience, especially, attuned to the way culture and credit intersect—Jackson becomes a mirror. The question is not only what he did with ice cream. The question is what America does with innovators like him: how quickly it turns their labor into lore, how rarely it preserves their methods, and how often it needs a mythic title (“Father of Ice Cream”) to justify paying attention at all.

There is a final, practical lesson embedded in the romance of the churn. Jackson’s likely contribution was about controlling variables—temperature, timing, formulation, packaging—in a system defined by melt. That is what building anything looks like for people working without institutional protection: you learn to operate inside volatility. You learn to make consistency out of unreliable conditions. You learn to turn a perishable craft into a business.

In a country that still struggles to recognize Black innovation unless it can be turned into a simple “first,” Augustus Jackson’s real legacy may be more useful than the legend. It is the story of process—of making a product repeatable—and of how repeatability, in the end, is what changes the world.

More great stories

The Man Who Outwrote the Fugitive Slave Law