Brown’s life spans a series of American contradictions that are still with us: the insistence on democratic ideals alongside the profitable maintenance of racial hierarchy.

Brown’s life spans a series of American contradictions that are still with us: the insistence on democratic ideals alongside the profitable maintenance of racial hierarchy.

By KOLUMN Magazine

If you want to understand William Wells Brown the way he understood himself, don’t begin with a genre. Begin with a problem. He was born into a system that treated Black life as movable property and Black knowledge as a liability. He escaped that system and then had to survive the new reality of being both free and, by law, reclaimable. He became famous in a country where fame could function like a lantern for slave catchers. And he did it all while building an output so various—slave narrative, travel writing, novel, drama, history, biography, lecture—that later critics have struggled to file him neatly into “author” or “activist” or “publisher.” The point, for Brown, was never neatness. The point was leverage.

Brown’s life spans a series of American contradictions that are still with us: the insistence on democratic ideals alongside the profitable maintenance of racial hierarchy; the ways public memory is curated to flatter power; and the belief—then and now—that the story you can get printed is a form of political territory. Brown’s genius was recognizing that territory early. He didn’t merely speak against slavery; he tried to out-produce it, to flood the culture with counterevidence. Encyclopaedia Britannica calls him the first African American to publish a novel and notes his pioneering work in travel writing and drama as well. But even that summary can understate the lived stakes. Brown’s writing career begins in the shadow of capture and forced return. It becomes, in time, a strategy for staying visible on his own terms.

That visibility was never passive. Brown was not only a writer; he was a professional abolitionist who moved across the same lecture circuits as the better-remembered Frederick Douglass, and he developed a performance style that used song, humor, and spectacle to translate the daily brutality of slavery for audiences who could otherwise treat it as abstraction. Accounts of his circuit work emphasize the way he would deploy props—among them a metal slave collar—to make the institution’s violence tactile rather than rhetorical. The effect was not simply emotional. It was organizational. The abolitionist movement ran on testimony, moral shock, and money; Brown’s body and voice were part of the movement’s infrastructure.

He would also become, as one University of Georgia Press volume puts it, among the most widely published and versatile African American writers of the nineteenth century—despite having been denied education in slavery. This is not inspirational varnish; it is a clue to his method. Brown made versatility into self-defense. Every form was a vehicle. Every audience was a potential node in a broader network of resistance.

A childhood engineered for disposability

Brown was born in Kentucky in 1814, enslaved, and raised under conditions that trained him to be useful and replaceable. He would later write about being sold multiple times before adulthood, a repeated uprooting that was common under slavery’s market logic and devastating for family continuity. Modern biographical summaries note that his mother, Elizabeth, had multiple children and that Brown’s father was white; as with many enslaved people of mixed ancestry, that fact conferred no protection.

What mattered to Brown later was not simply that slavery was cruel, but that it was administrative: it made intimacy into paperwork, turned parentage into ownership disputes, and converted geography into a trap. In his telling, the violence is both physical and procedural—the kind of violence that does not always look like a beating, but like an invoice.

By his teens Brown had been hired out and moved through work that brought him into contact with the wider mechanics of the slave economy. He spent formative years in and around Missouri and the river systems that functioned as commercial arteries for the country. Those river routes were not incidental scenery; they were a tutorial in how America moved. Later, as a free man in Buffalo, he would work on steamboats on Lake Erie—this time using the water not to transport commodities for enslavers, but to help transport fugitives toward Canada. Brown later claimed that in a seven-month period in 1842 he helped dozens of people reach freedom.

The impulse to turn infrastructure against itself—using boats, routes, schedules, and cover stories as tools—becomes a recurring motif in Brown’s life. It is also a reminder that abolition was not only argument. It was logistics.

Escape, reinvention, and the invention of the “professional fugitive”

Brown escaped from slavery in 1834, reaching Ohio and then moving into the abolitionist world that could, at its best, offer a precarious form of patronage and protection. He married, began building a family, and eventually settled for a period in Buffalo—an anti-slavery hub with proximity to Canada and a dense ecosystem of activists, conventions, and debate.

Buffalo matters here not because it is romantic but because it helps clarify what Brown was becoming: a man who understood that freedom for one person could be expanded only through systems. A Washington Post historical essay, written in a different context, notes Buffalo’s significance for antislavery organizing and points out that Brown made the city his home, situating him inside a broader landscape of conventions and Underground Railroad activity.

In this period Brown begins to emerge as a speaker and organizer who also writes. Writing, for him, was never simply personal catharsis; it was a means of circulating usable knowledge. By the 1840s and early 1850s, the abolitionist movement had a robust print culture—newspapers, pamphlets, subscription networks, and fundraising mechanisms that depended on readers who were willing to pay for a moral cause. The Atlantic, in an essay about abolition’s realities, emphasizes the importance of Black support for abolitionist print institutions and Black-led newspapers. Brown belongs to that world not as an ornament but as an operator.

Then the law changed in a way that recast his entire life.

The Fugitive Slave Act and the logic of exile

In 1850 Congress passed the Fugitive Slave Act, hardening federal enforcement and increasing the power of slave catchers even in free states. For people like Brown—public, identifiable, and formerly enslaved—the act created a grotesque paradox: the more effective you were as an abolitionist lecturer, the easier you were to seize. Brown was in Britain when the act passed. He stayed abroad for several years rather than risk capture. Britannica notes this period of travel and lecturing, and other summaries emphasize how the law shaped his decision to remain overseas.

Exile became an opportunity. In Britain, Brown could speak with a different kind of authority: not only as a survivor but as a living indictment of American democracy before an international audience. He also gained access to publishers and readers who were hungry for accounts of the United States’ “peculiar institution.” The transatlantic abolitionist movement was not a side story; it was a pressure system. Brown learned to operate within it.

In 1852 he published Three Years in Europe, a travel narrative that, as Britannica notes, marked another “first”—a Black-authored travel book reaching publication in this period. Travel writing might sound like a detour from slavery’s urgencies, but for Brown it was a way to reverse the gaze. Instead of being studied as a “problem” by white Americans, he studied Europe and America comparatively—politically, culturally, and morally. He was building a vantage point.

A Washington Post review of David McCullough’s work recalls Brown’s presence at an international peace congress in Paris, where he spoke about the need to break “every yoke of bondage,” and describes how he moved through European intellectual circles with a visibility that would have been lethal at home. The detail matters because it complicates a common simplification: that formerly enslaved people who went to Britain were merely “safe.” Brown was working. He was lobbying the conscience of foreign publics, translating his own life into geopolitical argument.

It was also in London that he published the book that would become his most famous artifact—and, in some ways, his most enduring disruption.

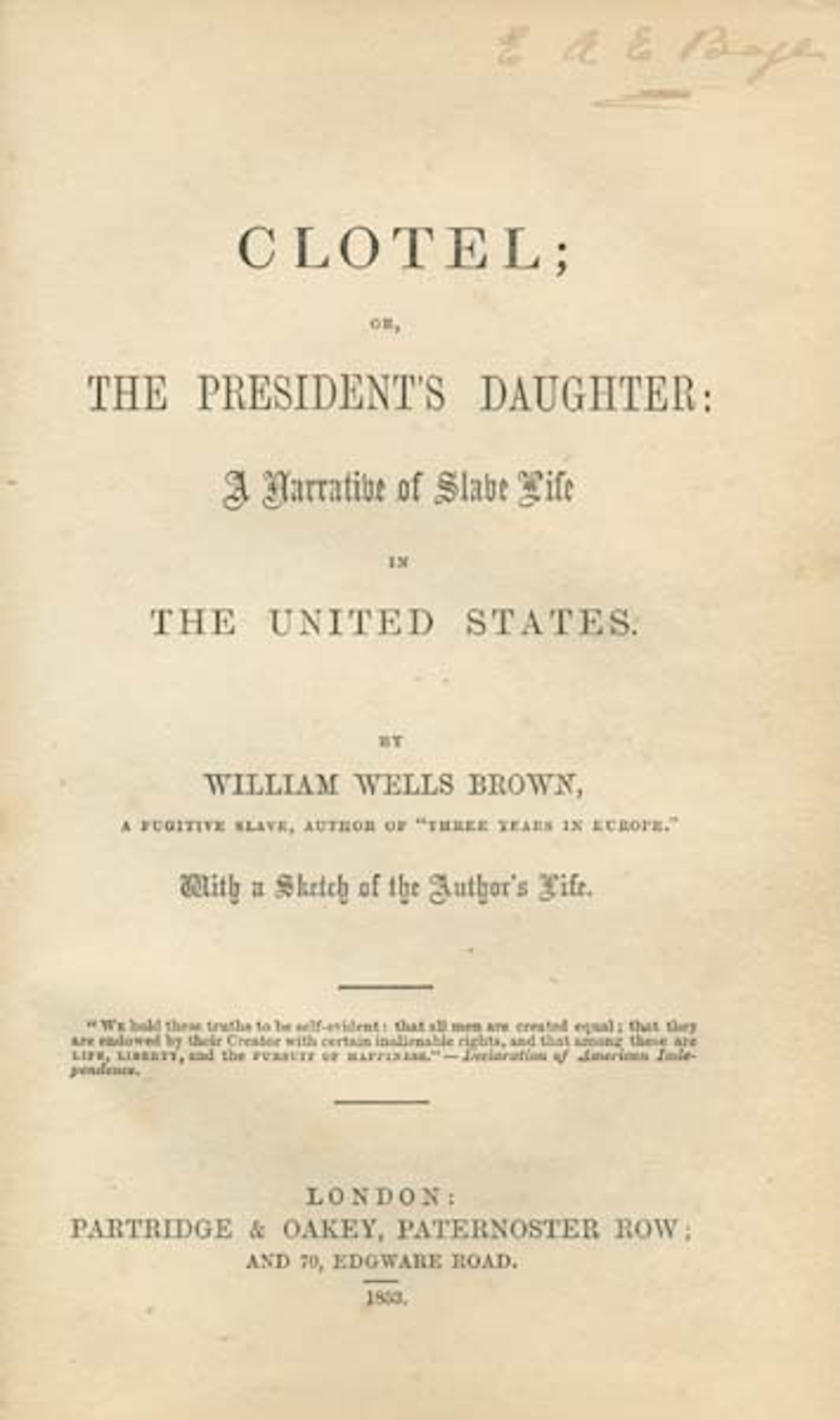

Clotel and the audacity of turning rumor into indictment

In 1853 Brown published Clotel; or, The President’s Daughter, widely described as the first novel published by an African American. The plot is built around a rumor that circulated widely in the nineteenth century: that Thomas Jefferson had fathered children with Sally Hemings. Brown seized on the rumor not to gossip but to prosecute. By imagining Jefferson’s mixed-race progeny sold into slavery, he forced readers to confront what the nation preferred to keep unspoken: the intimate entanglement of white power with sexual coercion, and the way slavery made kinship irrelevant when set against property.

Encyclopedia Virginia summarizes the novel’s significance, noting its London publication and its status as the first African American novel in print. The Guardian, in a later essay about “passing,” calls Clotel perhaps the first American passing novel and highlights how Brown used passing to expose the arbitrariness of white privilege. That framing helps explain why Clotel still reads like more than an artifact. It is not only antislavery sentiment; it is an experiment in how race is made—performed, policed, and monetized.

Brown’s formal choices were strategic. He stitched together documents, newspaper-style material, scenes that read like melodrama, and moral argumentation. The goal was to reach readers across tastes: those who wanted sensation, those who wanted evidence, those who wanted sermon, those who wanted plot. In the nineteenth-century literary marketplace, the line between activism and entertainment was not always a weakness; it was a distribution method.

Brown’s reputation has sometimes been hemmed in by the label “first.” First Black novelist, first Black playwright, first this, first that. But “first” is only the beginning of the more interesting question: what did he think a novel could do that a speech could not?

A speech travels through rooms. A novel travels through time.

The success of Clotel—and the debates it provoked—also underscore another part of Brown’s significance: he understood “publication” as a kind of citizenship claim. A Black author in 1853 asserting narrative authority over the life of a Founding Father was not merely writing literature; he was contesting the boundaries of who could interpret the nation.

The publisher as performer: Lecturing, spectacle, and abolition’s stagecraft

Brown’s writing life cannot be separated from his stage life. Long before social media collapsed the distinction between “content” and “performance,” Brown was operating in a world where the message often depended on the delivery. Abolitionist lectures were events—ticketed, promoted, reviewed, sometimes heckled, and always politically fraught. Brown developed a persona that could move between moral seriousness and satire, between direct testimony and broader cultural critique.

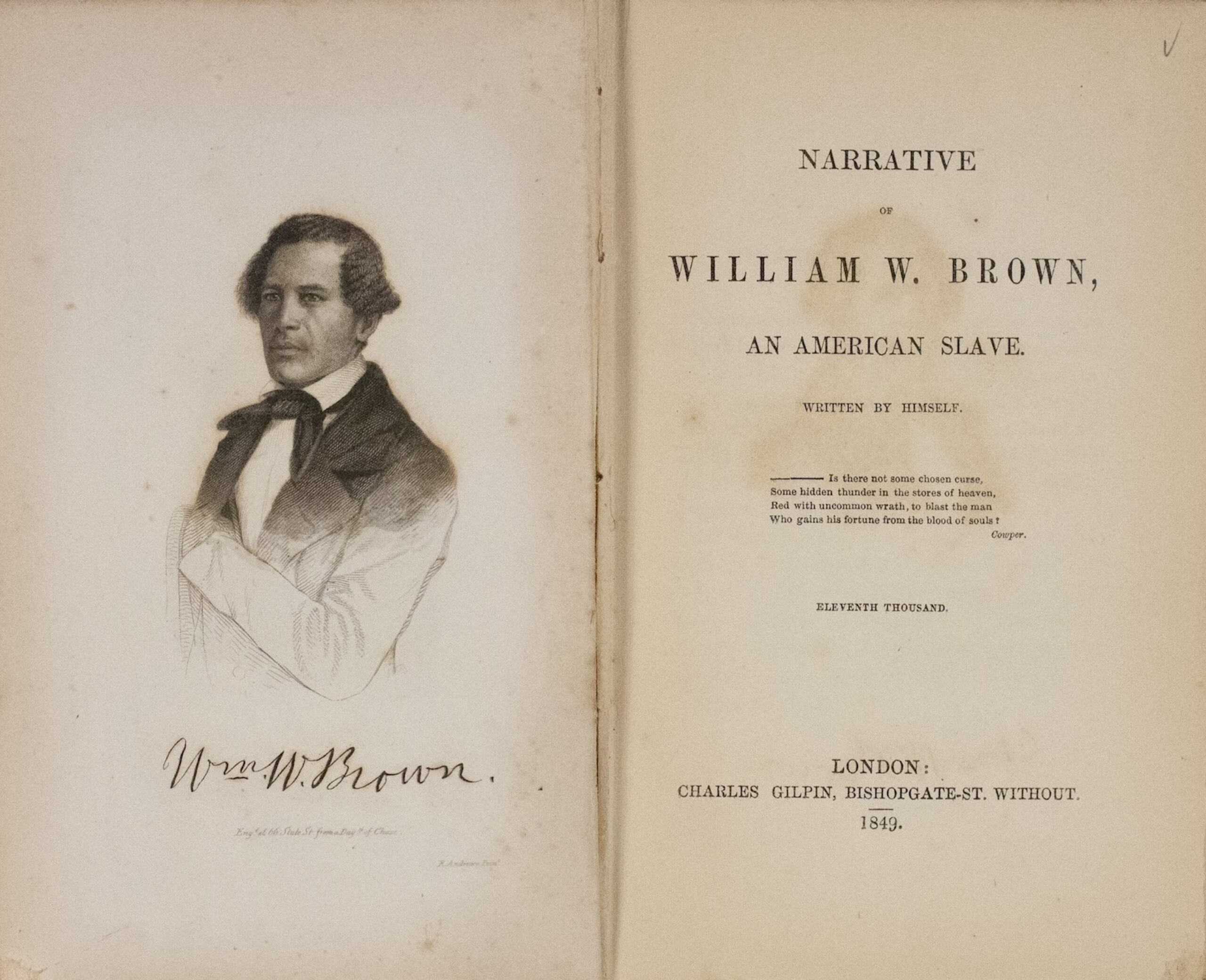

His first autobiography, Narrative of William W. Brown, a Fugitive Slave (1847), gave him a textual anchor for his public identity: a book he could sell, cite, and circulate as both evidence and livelihood. While this narrative fits within the broader tradition of fugitive slave narratives, Brown’s trajectory differs from many of his contemporaries because he did not stop at testimony. He treated testimony as a platform from which to build an entire publishing career.

That decision matters. The slave narrative is often taught as an endpoint: a singular account of bondage and escape. Brown treated it as a beginning.

The first published Black play, and the politics of the living room

In 1858 Brown published The Escape; or, A Leap for Freedom, widely considered the first published play by an African American. Britannica includes this among his pioneering achievements in drama. He often read the play aloud on the lecture circuit rather than delivering a conventional address, blending theater with activism. The choice is revealing. Plays do not merely argue; they model behavior. They show characters making decisions under pressure. They invite audiences to identify, to imagine, to rehearse emotions that might later become political will.

Brown’s theater work also suggests a sophisticated awareness of domestic space. Many antislavery novels and plays were consumed in parlors, not just public halls. By writing drama, Brown was inserting abolition into the culture’s leisure time—forcing slavery into the realm where people liked to believe themselves most “civilized.”

Historian of Black presence: Writing against national amnesia

After the Civil War, Brown continued to publish widely, turning more explicitly toward history and collective biography. This shift is sometimes described as a move from activism to scholarship, but that framing can mislead. For Brown, historical writing was activism by other means: a fight against erasure.

The UNC “Documenting the American South” collection preserves The Black Man: His Antecedents, His Genius, and His Achievements (1863), a work that functions as both compilation and argument—an assertion that Black achievement has a lineage, that genius is not an exception, and that the archive can be built even when institutions refuse to build it for you. If slavery tried to strip Black people of history, Brown responded by manufacturing a counter-history, name by name.

He later wrote The Negro in the American Rebellion (1867), often cited as among the first histories of Black military participation, and other works that tracked Black life through revolutions and nation-making. These books are not neutral chronicles. They are interventions in a postwar battle over memory: who counts as a founder, who counts as a citizen, who counts as the nation’s subject rather than its object.

In this sense Brown anticipates a modern argument about narrative power: that the struggle is not only over laws but over what future generations will think happened.

The Douglass problem—and the cost of charisma

Any honest account of Brown’s significance has to contend with a basic fact: he is often introduced in relation to Frederick Douglass. That’s partly because Douglass was an extraordinary orator and political figure. It is also because the culture of commemoration tends to prefer singular icons over complex ecosystems.

But Brown’s career complicates the Douglass-centric narrative. He was a contemporary and, at times, a rival. Biographical summaries note that Brown could be overshadowed by Douglass’s charisma and that the two feuded publicly. That tension is not gossip; it is a window into movement politics. Abolition was not a unified choir. It was a contested coalition with competing strategies, egos, and visions for how Black leadership should operate in public.

Brown’s temperament—more satirical, more genre-shifting, more willing to inhabit the role of “author” as well as “orator”—made him less easily mythologized. He was not a singular symbol; he was a working writer. And the culture often forgets the workers.

Ezra Greenspan’s biography, as discussed in a review from The Georgia Review, frames Brown’s “transformation from a slave into a professional abolitionist, performer, and author” as the guiding thread of his life. The phrase “professional” is key. Brown had to earn a living inside the movement while also serving it, a balance that shaped not only what he wrote but how quickly and how broadly he wrote.

A life stretched across borders: Britain, France, and the internationalization of Black critique

Brown’s years abroad are sometimes treated as a holding pattern forced by the Fugitive Slave Act. But they were also formative in building an international Black intellectual presence.

The Guardian’s reference to Three Years in Europe as a useful research text in a contemporary excerpt is small but telling: Brown’s travel writing has remained part of the long record of Black observation of Europe, a counterpoint to the dominant travel narratives of the era. His presence at European congresses and in elite circles, described in secondary accounts, also illustrates something that abolitionists understood well: Britain’s moral judgment mattered to America’s self-conception.

When Brown’s freedom was purchased by British supporters in 1854, enabling him to return to the United States with less risk of re-enslavement, it signaled another truth about abolition: sometimes liberation required not only courage but fundraising. Brown’s very body, in that moment, became a transaction that exposed the grotesque symmetry of slavery’s economics and abolition’s counter-economics.

Brown as “publisher”: What it means to control distribution

Calling Brown a “publisher” can be misleading if we interpret it narrowly as someone who ran a printing press. Brown’s publishing significance is broader: he was a man who understood that distribution is power.

He published across multiple venues and markets—U.S. abolitionist circles, British presses, postwar American readers—and he repackaged his life and ideas for different audiences without surrendering the moral core. He also understood the value of compilation, excerpt, reuse, and revision. Clotel itself exists in multiple versions over time, revised and reshaped as political contexts changed. That adaptability looks modern because it is modern: it is content strategy in the service of survival.

In the nineteenth century, Black writers often faced constrained access to mainstream publishers and reviewers. Brown’s answer was to become a one-man ecosystem: to write quickly, speak constantly, and treat every book as both a text and a tool.

This is why the “firsts” matter less than the system he built. Brown’s career models what it looks like to create a public intellectual life when the state has marked you as a fugitive.

The Buffalo years and the geography of abolition

Brown’s connection to Buffalo is more than a biographical detail; it is a map of how freedom worked. Buffalo functioned as a node between the United States and Canada, between the legal regime of slavery and the possibility of flight. Brown’s work on the water, helping fugitives escape, underscores that abolition was enacted not only through speeches but through coordinated action embedded in everyday labor.

In our own era, when we talk about “mutual aid” and “networks,” Brown’s life offers a historical precedent: a man using his job to create covert pathways toward safety, then using his writing to publicize the moral stakes of those pathways without exposing the people who traveled them.

Relevance now: Race as construct, archives as battlegrounds

Brown’s most lasting ideas feel startlingly contemporary because they address problems that have never been fully resolved.

First, Clotel anticipates modern scholarship on race as a social and legal construction. By centering “passing,” Brown dramatized how the category of “white” could be performed and policed, and how privilege could attach to appearance rather than morality. The Guardian’s discussion of Clotel in the context of passing narratives underscores this conceptual legacy.

Second, Brown’s historical works anticipate a continuing fight over curriculum, commemoration, and the public archive. When he assembled Black biographies and military histories, he was doing more than celebrating; he was arguing against a default assumption of Black absence from national greatness.

Third, Brown’s career speaks to the precariousness of public truth-telling under hostile law. The Fugitive Slave Act did not just threaten his body; it threatened his speech. His choice to remain abroad, to publish in London, and then to return only after his freedom was purchased, demonstrates a strategic approach to risk that activists still recognize: you cannot organize if you are captured.

And finally, Brown’s life suggests a durable lesson about movements: charisma is not the only engine. Sometimes the engine is output—books, lectures, pamphlets, performances, histories—produced in volume, designed to outlast the moment.

Why he is still less famous than he should be

If Brown’s accomplishments are so foundational, why does he remain less widely known than Douglass or Harriet Jacobs or even later novelists?

Part of the answer is narrative convenience. Brown is difficult to summarize because his career refuses a single arc. He is not only “the escaped slave who wrote a narrative.” He is also the transatlantic lecturer, the travel writer, the novelist of Jefferson’s shadow life, the playwright staging abolition, the historian compiling Black genius, the organizer using boats as corridors to freedom.

Another part is institutional memory. The canon often privileges certain genres—especially the slave narrative—over the messy hybrid forms Brown loved. His willingness to blend documentation with melodrama, satire with sermon, and performance with print has sometimes made critics uneasy. Yet that hybridity is precisely what made him effective in his own time. It allowed him to reach audiences who would never attend an abolition meeting but might read a sensational novel.

In other words, Brown’s “problem” has always been that he operated like a modern media figure in a culture that prefers its heroes in one format at a time.

The long echo of a life spent making evidence

Brown died in 1884 in Massachusetts. By then, the nation had abolished slavery but was building new systems of racial control, including the legal and extralegal architecture that would harden into Jim Crow. Brown’s work, read now, feels like a record from inside a pivot point: the moment when Black freedom was being debated not as a metaphor but as policy, and when Black authorship was still a radical claim.

To read Brown closely is to see that he never believed the United States would transform simply because it was shamed. He believed it would transform only if it was confronted—again and again, across mediums, across borders, across decades—with the evidence of what it had done and what it was doing.

That is what makes him not merely a “first” but a template. Brown’s life argues that publication can be a form of liberation—not because a book magically changes the world, but because a book can keep a truth alive long enough to find the people ready to act on it.

And in that sense, William Wells Brown remains painfully current: a man who understood that if power controls the story, it controls the future—so you had better learn how to print.

More great stories

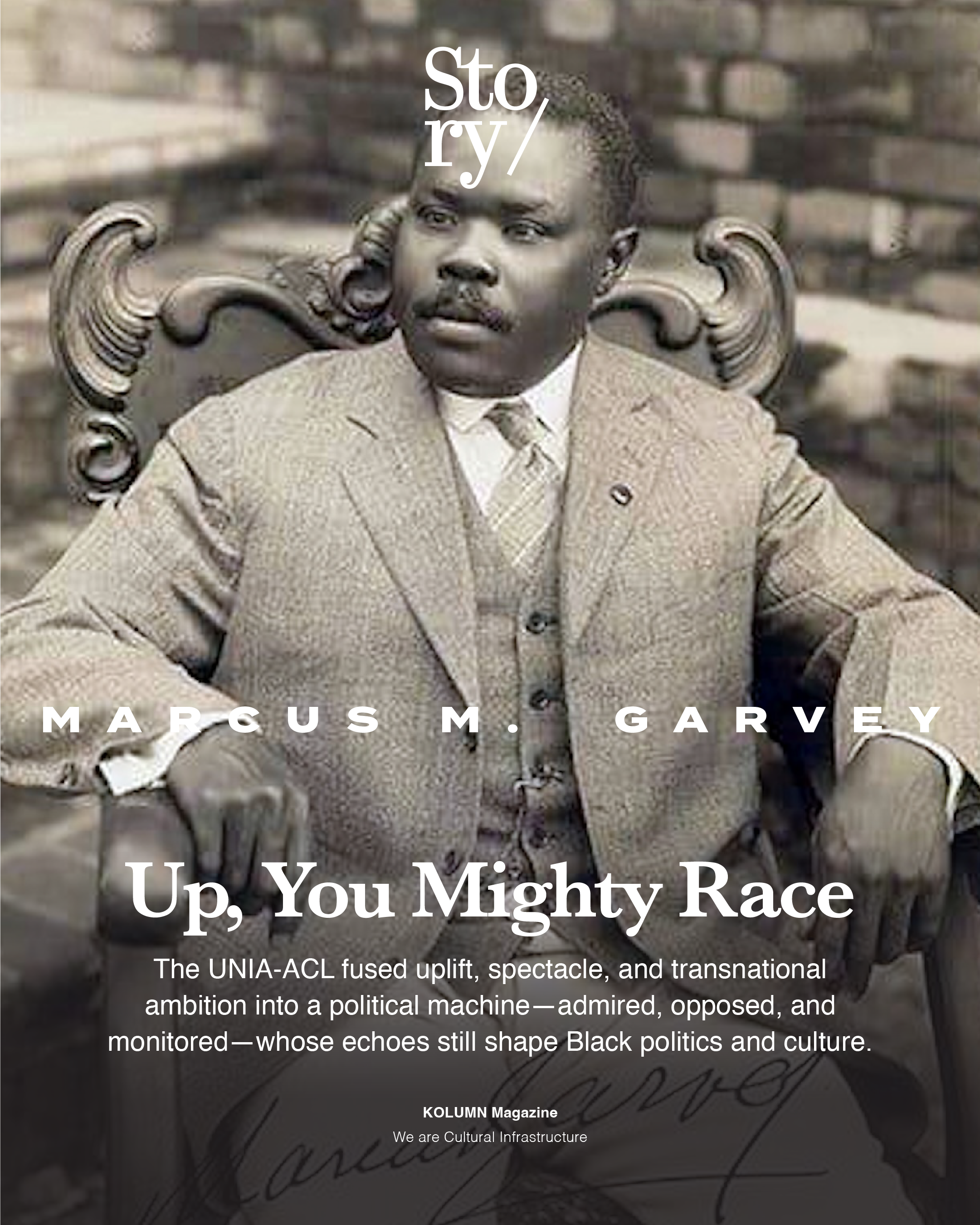

Up, You Mighty Race