Long before Selma became shorthand for democracy under pressure, Lafayette was helping to engineer the conditions that made Selma possible.

Long before Selma became shorthand for democracy under pressure, Lafayette was helping to engineer the conditions that made Selma possible.

By KOLUMN Magazine

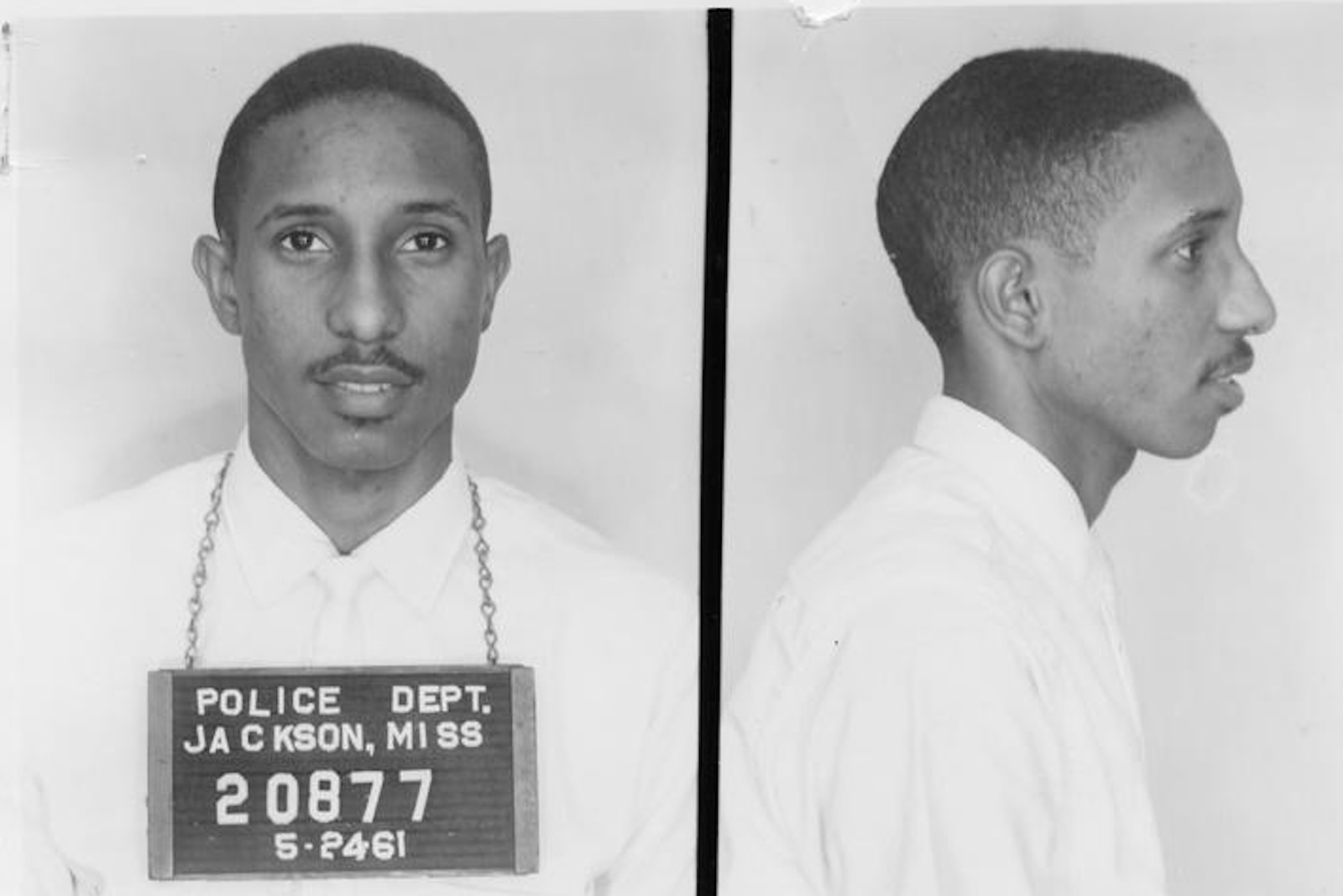

A movement is remembered by its photographs: a lunch counter with a line of young people sitting like they have nowhere else to be; a bus terminal that looks, in hindsight, like the stage set for American conscience; a bridge in Alabama where the future seemed to lurch forward and then recoil into batons and gas. The modern story of the civil rights era often arrives already edited—its climaxes pre-selected, its heroes already cast, its slogans already trimmed for granite.

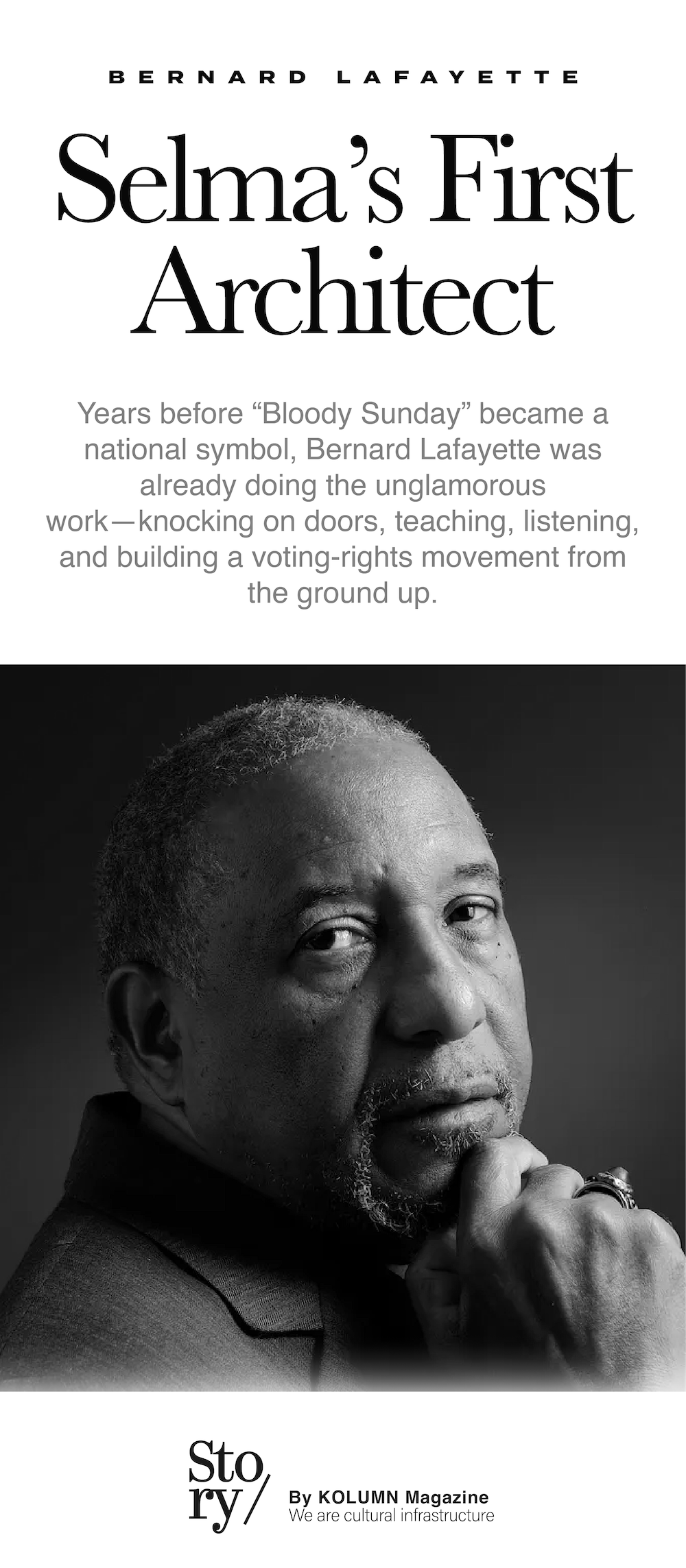

Bernard Lafayette’s life resists that kind of easy packaging, not because his résumé lacks drama, but because his central talent has always been the thing that drama tends to obscure: preparation. His career is a case study in how history is rehearsed. Long before Selma became shorthand for democracy under pressure, Lafayette was helping to engineer the conditions that made Selma possible—patiently, methodically, and with a minister’s attention to human frailty. In Nashville, he learned nonviolence not as vague moral preference but as an applied craft. In the Freedom Rides, he learned how quickly craft becomes ordeal. In Selma, he learned that movements do not “happen” so much as they are built—brick by brick—under constant threat of collapse.

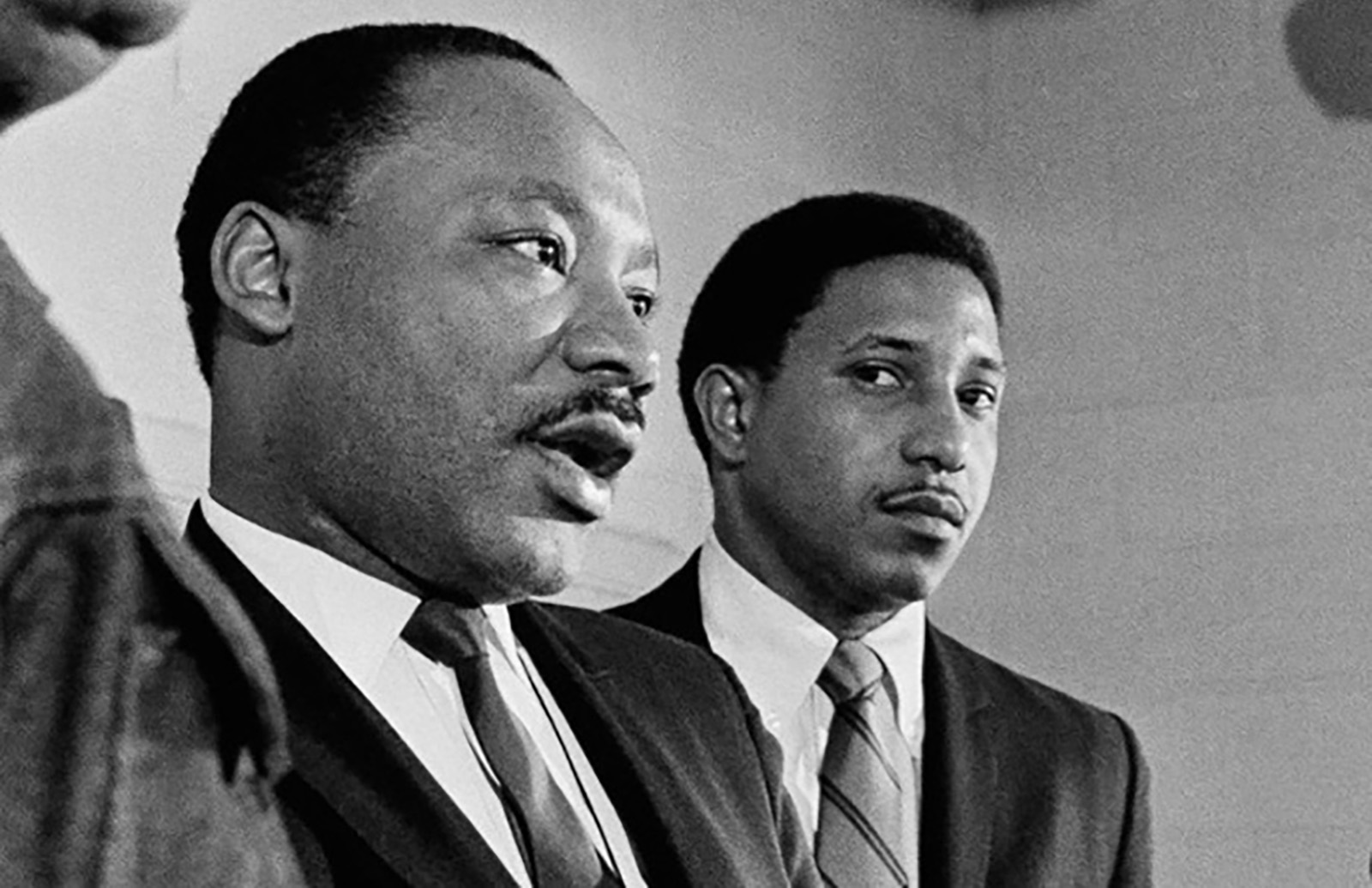

That he is sometimes described as an “authority” on nonviolent social change can sound like the bland praise offered to elders at commemorations. But Lafayette’s authority was earned under conditions designed to erase it. He was part of the Nashville Student Movement that treated training as seriously as action. He worked with the Student Nonviolent Coordinating Committee (SNCC) in the early 1960s, when SNCC’s identity was still being contested, and the price of being “young” and “radical” could be prison, a beating, or worse. He became central to the early organizing in Selma, Alabama, years before the marches that would become national news. He later served in the Southern Christian Leadership Conference (SCLC), and after Martin Luther King Jr. brought him into SCLC’s orbit as a program coordinator, Lafayette took on major responsibility for the 1968 Poor People’s Campaign, a project that forced the movement to grapple explicitly with economic justice and multiracial coalition at a moment of profound grief and fragmentation.

If you want to understand Lafayette, you have to pay attention to how he talks about power. He is not primarily the kind of activist whose story is told through one signature speech or one famous confrontation with a television camera. His story is told through systems—training systems, voter-registration systems, movement communications systems, and the slow, often invisible systems by which people learn to keep going after fear has done its work. When he appears in other people’s narratives—John Lewis’s remembrances of Nashville, accounts of the Freedom Rides, reflections on the moral technology of nonviolence—he often shows up as a co-worker and co-thinker: someone in the room when decisions were made, someone trusted to execute them, someone tasked with the hard part.

This is a life shaped by proximity: to the great names of the era, yes, but also to the local leaders and ordinary people who made those great names matter. Lafayette spent decades insisting—by example as much as by argument—that the civil rights movement was not a miracle. It was logistics, ethics, training, and community, assembled under terror.

A childhood that taught him movement is motion

Bernard Lafayette Jr. was born in Tampa, Florida, in 1940, into the segregated South that would later claim his young adulthood as both target and training ground. Even the basics of his early life contain the seeds of the organizer he would become: movement, relocation, adaptation. Accounts of his childhood note that his family moved around, including time in Philadelphia where he experienced an integrated community—an early glimpse of social arrangements not ordered by Jim Crow. Such details matter because organizers are often people who have learned, early, that the world is not fixed. A different arrangement exists somewhere. If it exists somewhere, it might be built elsewhere.

When Lafayette later arrived in Nashville to attend school at the American Baptist Theological Seminary (often referenced today as American Baptist College), he entered a city whose Black institutions—its historically Black colleges and universities, its churches, its student networks—were already incubating a particular kind of activism: disciplined, collective, and intellectually serious. Nashville’s student movement, which helped shape figures like John Lewis and Diane Nash, is often described as a training ground, and that word is accurate. It was not a metaphor. It was an intentional method.

The National Park Service, in a profile of Lafayette, emphasizes how central those weekly meetings with James Lawson were to his development: sessions that taught methods of nonviolent protest and helped spark the organizing infrastructure that would feed SNCC and related campaigns. The “spark” language can make it sound spontaneous. In reality, the spark came from repeated, structured education—role-playing, discussion, the building of shared discipline. Lafayette absorbed nonviolence as something closer to martial training than moral aspiration: how to refuse retaliation under assault; how to stay coherent under verbal abuse; how to hold a line when the point of the attack is not simply to harm you but to make you harm yourself—by losing your composure, by breaking your own commitments, by becoming the caricature your opponents need you to be.

That last part—nonviolence as refusal to become your enemy’s story—threads through the rest of his career. It is also why Lafayette’s work is sometimes described in terms of strategy rather than sanctimony. In a Guardian piece reflecting on the concept of “grit,” Lafayette appears as a veteran whose resilience is inseparable from technique; in another Guardian article about the 60th anniversary of Bloody Sunday commemorations, his comments pivot quickly from commemoration to capacity-building—how communities defend themselves economically as well as politically. These later interventions can read as the concerns of an elder. They are also consistent with what he practiced early: the belief that moral clarity without infrastructure is fragile.

Nashville and the making of a method

The Nashville sit-ins and related campaigns are often remembered as the prelude to larger, more nationally mythologized battles. But for Lafayette and his cohort, Nashville was formative in its own right: an environment where young people turned theory into muscle memory. Lafayette was among those who helped lead sit-ins challenging segregated businesses, part of a cohort that included Diane Nash, James Bevel, and John Lewis. In standard movement histories, these names are often presented as a constellation, and there is truth in that: their work was collaborative, mutually reinforcing. Yet even within a constellation, different stars do different work.

Lafayette’s work frequently centered on the how. How do you build a group that can take abuse without dissolving? How do you create a shared discipline strong enough that strangers can act like a unit? How do you help people who have every rational reason to fear violence choose to move anyway?

One answer is training, and the Nashville movement treated training as its hidden engine. Another answer is moral imagination: the capacity to believe that the humiliation you endure publicly can be converted into pressure privately. This conversion requires performance, not in the theatrical sense of insincerity but in the sense of staging. Nonviolent direct action, as Lafayette practiced it, stages injustice so it cannot hide. But staging is not the same as spectacle. It is closer to procedure: identify the pressure point; prepare the participants; anticipate the response; respond in a way that exposes the system rather than feeding it.

If this sounds like the language of an operations manual, it is because Lafayette and his peers were, in effect, writing an operations manual for a social revolution. They were inventing, in real time, a new kind of public confrontation—one that used the body as evidence and the refusal to retaliate as an indictment. The aim was not to win a fight. The aim was to win legitimacy.

The Washington Post, in a short video segment reflecting on a Nashville lunch-counter sit-in, notes Lafayette alongside John Lewis, linking both men to the city’s direct-action campaigns and to the broader lineage of nonviolent protest. The Atlantic, in commemorations of Lewis, similarly places Lafayette among those who pioneered the tactics that Lewis would later carry into national prominence. These references are telling: Lafayette becomes a recurring supporting character in the story of others because his work was often foundational—helping build the conditions that made those others’ most visible moments possible.

The Freedom Rides and the education of fear

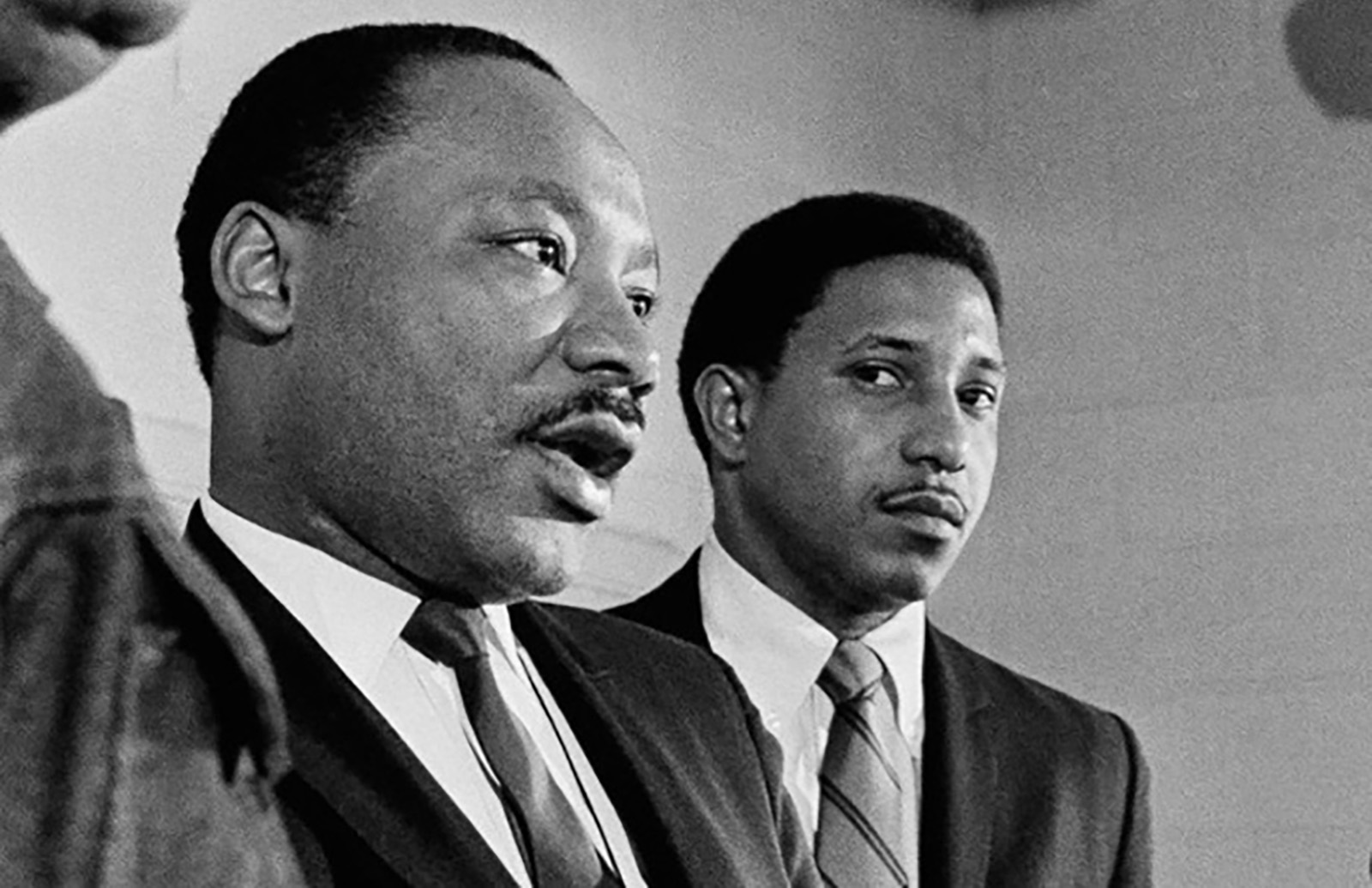

If Nashville trained Lafayette in discipline, the Freedom Rides tested the limits of discipline under terror. In 1961, when the Congress of Racial Equality initiated the Freedom Rides to enforce federal integration laws on interstate bus routes, the project combined moral provocation with legal confrontation. Integrated groups of riders would travel through the Deep South, deliberately violating segregation codes in bus terminals and on buses, forcing the federal government to either protect constitutional rights or reveal its weakness.

Lafayette, still very young, was among those who joined the effort after violence erupted against the initial riders. Accounts emphasize that Nashville students, trained in nonviolence, resolved to continue the rides after earlier riders were attacked. In other words, the Freedom Rides became not only a test of segregation but a test of the movement’s resolve: could the commitment to nonviolence survive when opponents used violence as a policy?

The Freedom Rides are often remembered through particular scenes: the burning bus in Anniston, the mob in Birmingham, the violence in Montgomery. Lafayette’s experience intersects with those scenes. He was beaten and arrested; he endured the kind of mob threat that makes the word “courage” feel too small. A Washington Post archive review of a Freedom Rides book captures one moment with cinematic dread: the sense, as a bus approaches a station, that something is wrong, that the absence of protection is itself a message. The point of terror is not simply to harm a person; it is to tell everyone watching that the state is either complicit or irrelevant.

What happens to a person’s politics when that message is delivered repeatedly?

For Lafayette, the answer seems to have been a deeper investment in the mechanics of nonviolent struggle, not a retreat from them. This is not the only possible outcome. It is a choice. The movement produced people who embraced armed self-defense, people who left activism, people who turned to electoral politics, people who hardened into cynicism. Lafayette, by most accounts, doubled down on training and organizing—the work that converts fear into something usable. Over and over, he treated violence not as evidence that nonviolence was naïve but as evidence that nonviolence was effective—effective enough to provoke the system into revealing itself.

This logic can be misunderstood, particularly by people who encounter the movement first through its commemorations. There is a tendency to treat nonviolence as softness. Lafayette’s version of nonviolence is not soft. It is controlled. It is an insistence that you will not allow your opponent to dictate your behavior, even through pain.

Selma before Selma: The unglamorous groundwork

Selma’s most famous images—the marches, the bridge—arrived in 1965. But the groundwork began earlier, and Lafayette was central to it. The SNCC Digital Gateway, a documentary project created by the SNCC Legacy Project and Duke University, describes Lafayette and his wife, Colia Liddell Lafayette, going to Selma in 1963, where he became the director of SNCC’s Alabama voter registration project. That phrasing matters. Director. Project. Registration. These are administrative words, and they belong in the story. Selma was not simply a spontaneous eruption of protest. It was a campaign with structure, leadership, and ongoing local relationships.

The Selma that Lafayette entered was a place where Black people lived under a tight lattice of voter suppression, economic coercion, and physical terror. The Dallas County Voters League, a local organization, was already part of the landscape. Lafayette’s role, as described in multiple sources, involved working with local leaders—meeting people where they were, hearing their experiences, and building the collective confidence required to attempt registration in a county where trying to vote could cost you your job, your home, or your life.

On the night of June 12, 1963—the same night Medgar Evers was murdered—Lafayette was severely beaten in Selma. It is difficult to overstate what that coincidence means psychologically: to be assaulted on a night when the movement is simultaneously absorbing news of another assassination attempt. The message from the segregationist order was consistent across the South: activism will be met not simply with arrest but with bodily harm. Yet Lafayette continued. The beating did not end his organizing work. If anything, it underscored the necessity of building a movement strong enough that no single person’s injury could stop it.

This is where Lafayette’s temperament becomes politically significant. Some activists were drawn to the dramatic confrontation. Lafayette appears, across accounts, as someone drawn to the longer arc: the building of a local base, the education of new participants, the relationship between outside organizers and local communities. His time in Selma belongs to the phase of a movement that rarely gets film treatment: the phase where the big moment is not yet visible, where the work is routine and dangerous, where success is measured in small increments—a new person registered, a new meeting held, a new fear overcome.

By late 1964 and early 1965, as SCLC decided to join and amplify the Alabama voting-rights struggle, Selma became the focal point of a national campaign. Lafayette’s earlier work, along with the local organizing already underway, made that amplification possible. In the standard narrative, King “comes to Selma.” In the organizer’s narrative, Selma is already working when King arrives. Both can be true. But only one gives credit to the people who built the foundation.

The passage of the Voting Rights Act of 1965 is often described as the legislative fruit of the Selma-to-Montgomery marches and the televised brutality of Bloody Sunday. That is accurate, as far as it goes. But it can obscure the deeper truth: federal action became possible because local people had already been doing the work of a democracy the state refused them. Lafayette’s contribution was to help coordinate that work—translating moral demand into a campaign with strategy, messaging, and disciplined participation.

From SNCC to SCLC: Moving between movement cultures

Lafayette’s career also helps explain a less romantic reality about the civil rights era: the movement was not one organization with one style. It was an ecosystem of groups with distinct cultures—SNCC’s youth-led grassroots intensity, SCLC’s ministerial structure and national visibility, CORE’s direct-action provocations, the quiet infrastructure of groups like the American Friends Service Committee. To move between these worlds required more than fame. It required trust.

Lafayette appears to have been one of those connective figures, able to work within SNCC’s grassroots context and later within SCLC’s hierarchy. The Martin Luther King, Jr. Research and Education Institute at Stanford notes that King hired Lafayette as SCLC’s program coordinator in 1967 and that Lafayette then took on responsibility for the Poor People’s Campaign. This was not a ceremonial assignment. The Poor People’s Campaign aimed to widen the movement’s agenda from civil and voting rights into economic justice—housing, jobs, income, and the structural realities that made formal rights insufficient.

It is worth pausing on what it means to be tasked with that project in 1967 and 1968. The movement was facing intensified backlash, internal debates over strategy, and the exhaustion that comes from years of struggle. King was under immense pressure; the Vietnam War and economic inequality were sharpening political fault lines; Black Power debates were reshaping the movement’s internal landscape. To coordinate a campaign premised on multiracial poverty—bringing together Black, white, Indigenous, and Latino poor people into a shared demand—required both idealism and meticulous planning. It also required the kind of discipline Lafayette had been practicing since Nashville.

After King’s assassination, the Poor People’s Campaign continued under Ralph Abernathy, but the emotional and political terrain had shifted. To keep a campaign moving after the death of its most visible leader demanded the kind of behind-the-scenes leadership that history often forgets. Lafayette was part of that effort.

Chicago and the argument that civil rights is also public health

One of the most revealing chapters of Lafayette’s career is his work in Chicago, where civil rights organizing collided with northern forms of segregation—housing discrimination, environmental hazards, and the bureaucratic violence of neglect. The Chicago Freedom Movement is often remembered for the Open Housing Campaign, but organizers also confronted what Lafayette later described as slum conditions with direct consequences for health.

A Middlebury-hosted Chicago Freedom Movement profile describes Lafayette as the first of the leading southern civil rights activists to turn to organizing in Chicago, recruited to work for the American Friends Service Committee (AFSC) in 1964. The profile emphasizes that he worked on the city’s West Side and energized residents to mobilize against lead poisoning—an issue that reveals how racism functions not only through police and laws but through poisoned infrastructure.

This is a critical point for understanding Lafayette’s intellectual trajectory. By the mid-1960s, the movement’s agenda was expanding beyond access to lunch counters and ballot boxes into a broader confrontation with structural inequality. Lead poisoning, substandard housing, and neighborhood disinvestment were not simply “urban problems.” They were civil rights problems—unequally distributed harms, enforced by policy and indifference. Lafayette’s work helped frame these issues as part of the same moral universe as southern segregation.

In a 2006 piece published by the Poverty & Race Research Action Council (PRRAC), Lafayette writes about an “End-the-Slums” campaign that paralleled the more publicized open-housing focus, explicitly linking housing and health through research and advocacy. Even decades later, his framing remains contemporary: that civil rights must be understood as the right to live in conditions that do not slowly kill you.

Chicago also illustrates another dimension of Lafayette’s leadership: his ability to translate southern movement tactics into northern contexts without assuming they were identical. Northern segregation was often less explicit, more bureaucratic, easier for white liberals to deny. It required different kinds of exposure. But it still benefited from the same disciplined confrontation: forcing institutions to acknowledge what they were doing.

The minister and the educator: Institutionalizing a movement craft

Lafayette’s later career includes roles that, on paper, might look like a pivot away from frontline activism: ordained ministry, academic leadership, program directorships. In reality, these roles can be read as a continuation of his core commitment: turning nonviolence into a teachable discipline.

He became ordained as a Baptist minister and served in significant educational leadership roles. The King Institute notes his graduate education at Harvard and his continued involvement with institutions connected to King’s legacy. Other sources describe him as a founding director or senior fellow connected to peace and nonviolence studies initiatives, including work associated with the University of Rhode Island’s Center for Nonviolence and Peace Studies. These institutional settings matter because movements do not survive on memory alone. If a method is not taught, it becomes mythology. Lafayette spent decades working to prevent nonviolence from becoming mere nostalgia.

This is also where Lafayette’s temperament—his preference for training, preparation, and disciplined practice—found a natural home. Universities and seminaries can be places where social movements are either sanitized or strengthened. Lafayette’s presence in such settings suggests an attempt to strengthen: to ensure that the knowledge gained in the 1960s did not remain locked in the biographies of elders but became accessible to new activists confronting new forms of injustice.

A National Park Service profile published in 2025 frames him as a major civil rights activist whose early involvement in Lawson-led meetings in Nashville taught methods of nonviolent protest. That the NPS tells the story in terms of training is notable: it signals that the public memory of the movement is increasingly willing to foreground pedagogy as much as protest. Lafayette’s life helps make that shift possible because pedagogy was always part of his activism.

A philosophy of nonviolence that is neither passive nor naïve

It is tempting, in the present, to turn nonviolence into a personality type—gentle people doing gentle politics. Lafayette’s life argues against that. His nonviolence was forged in environments where passivity would have been suicidal. It was, instead, a form of control: control over one’s own response, control over the narrative a violent system wanted to impose, control over the shape of confrontation.

The Atlantic, in a readers’ response letter referencing Lafayette, captures one strand of his counsel: know your rights, know the law—use your rights or lose them. This is not the language of passive moral appeal. It is the language of civic maintenance. Rights, in Lafayette’s framework, are not permanent gifts; they are capacities that weaken when unused.

This emphasis fits his broader career. Voting rights work in Selma required detailed knowledge of registration procedures and the local mechanisms of suppression. Freedom Rides required knowledge of federal law and the ways southern authorities evaded it. Chicago housing work required understanding municipal structures and how neglect is produced. Even his later work in peace education and nonviolence studies required translating moral commitments into actionable curricula.

Lafayette’s nonviolence is, in that sense, legalistic in the best way: attentive to the systems that shape behavior. Moral outrage is not enough. You must understand the machine you are trying to change.

Proximity to King, and what it meant after Memphis

Lafayette’s relationship to Martin Luther King Jr. is often referenced as a credential, but it is more useful to treat it as a lens into Lafayette’s responsibilities at a pivotal moment. He was with King in Memphis in the period surrounding King’s assassination—accounts note Lafayette’s presence at the Lorraine Motel during King’s final days, and the Guardian has included him in live commemoration coverage that references that proximity. Such details, in movement history, matter not as gossip but as context: proximity often indicates trust. And trust often determines who is tasked with what.

King’s final years were marked by his expansion into economic justice and anti-war activism—stances that alienated some allies and intensified scrutiny. If King hired Lafayette as program coordinator in 1967 and placed him in key roles in 1968, it suggests that Lafayette was not simply a symbolic veteran but an operational leader trusted with the movement’s evolving agenda.

After King’s death, the question for many movement veterans became how to continue without being consumed by mourning or trapped by commemorative politics. Lafayette’s post-1968 work—continuing on the Poor People’s Campaign, shifting into educational roles, advising on nonviolent strategy—can be read as an answer: continue by institutionalizing the method, by training new people, by keeping the discipline alive.

The public memory of a movement, and the problem of simplification

One risk of writing about Lafayette is that his life intersects with so many famous chapters of the civil rights era that he can be reduced to a string of affiliations: Nashville Student Movement, SNCC, SCLC, Freedom Rides, Selma, Poor People’s Campaign, Chicago. The point is not simply that he was there. The point is what kind of “there” he represented.

Many narratives of the movement—especially those built for classroom summaries—focus on charismatic leadership and singular events. Lafayette’s career points toward a different truth: movements are sustained by people who are good at repeatable process. In modern terms, he is an organizer-educator, a strategist of human behavior. He operated in spaces where the central question was not “How do we feel?” but “What do we do next, and how do we train others to do it?”

This is why he keeps appearing in other people’s stories. In Barack Obama’s eulogy for John Lewis, Lafayette appears in an anecdote about an early, unsanctioned test of bus segregation—Lewis and Lafayette buying tickets, sitting up front, refusing to move. The anecdote is not primarily about Lafayette as individual hero. It is about how tactics are tested before they are formalized, how courage is rehearsed before it is televised. Lafayette, in that story, is part of the rehearsal.

Later years: Legacy as practice, not tribute

In recent decades, Lafayette has continued to speak publicly about nonviolence and social change. University event announcements and profiles describe him as a Freedom Rider and an authority on strategies for nonviolent change, emphasizing both his movement history and his ongoing teaching role. A 2019 University of Nebraska–Lincoln announcement, for example, notes his participation in the Freedom Rides, his role in early Selma organizing, his work with SNCC and SCLC, and his later role helping found nonviolence and peace studies initiatives.

What is striking about Lafayette in such contexts is that he does not present the 1960s as a museum. He presents it as a toolkit. The point of recounting a beating or a jail stay is not to demand reverence; it is to teach a lesson about how systems respond to pressure and how people can respond without losing themselves. In a time when “nonviolence” is often debated either as moral purity or political weakness, Lafayette’s life offers a third framing: nonviolence as skilled labor.

The Guardian’s 2025 reporting from Selma captures an elder activist whose attention is on the present—on strategy, economics, and what commemorations should produce beyond sentiment. Whether or not one agrees with every emphasis, the posture is consistent: stop treating history as an anniversary and start treating it as instruction.

Why Bernard Lafayette matters now

If you are searching for Lafayette’s “legacy,” it is tempting to locate it in the standard outputs of civil rights history: legislation, iconic images, famous speeches. Those are real. But Lafayette’s most durable legacy may be harder to photograph: the transmission of method.

He helped develop a model of activism in which moral goals are pursued through disciplined collective action—action that requires training, strategy, and a willingness to endure suffering without surrendering agency. He helped build voting-rights power in a place where attempting to vote was treated as an act of war. He participated in the Freedom Rides at a moment when the federal government’s promises were tested by southern violence. He took on the work of economic justice organizing and coalition-building at a moment when the movement’s future was uncertain. He helped translate southern civil rights organizing into northern struggles around housing and public health. He spent decades teaching nonviolence not as sentiment but as a practice that can be learned.

In an era when public protest can be instantaneous—organized in hours, distributed through phones—Lafayette’s life is a reminder that speed is not the same as durability. A movement is not only an outpouring. It is a discipline. It is what remains after the outpouring has passed and the backlash has begun.

And if that sounds like a sober conclusion, it fits the man. Bernard Lafayette’s career has never been about drama for its own sake. It has been about the quiet insistence that democratic change is built by people who keep showing up, keep training, keep organizing—until the nation has no choice but to look at itself.

More great stories

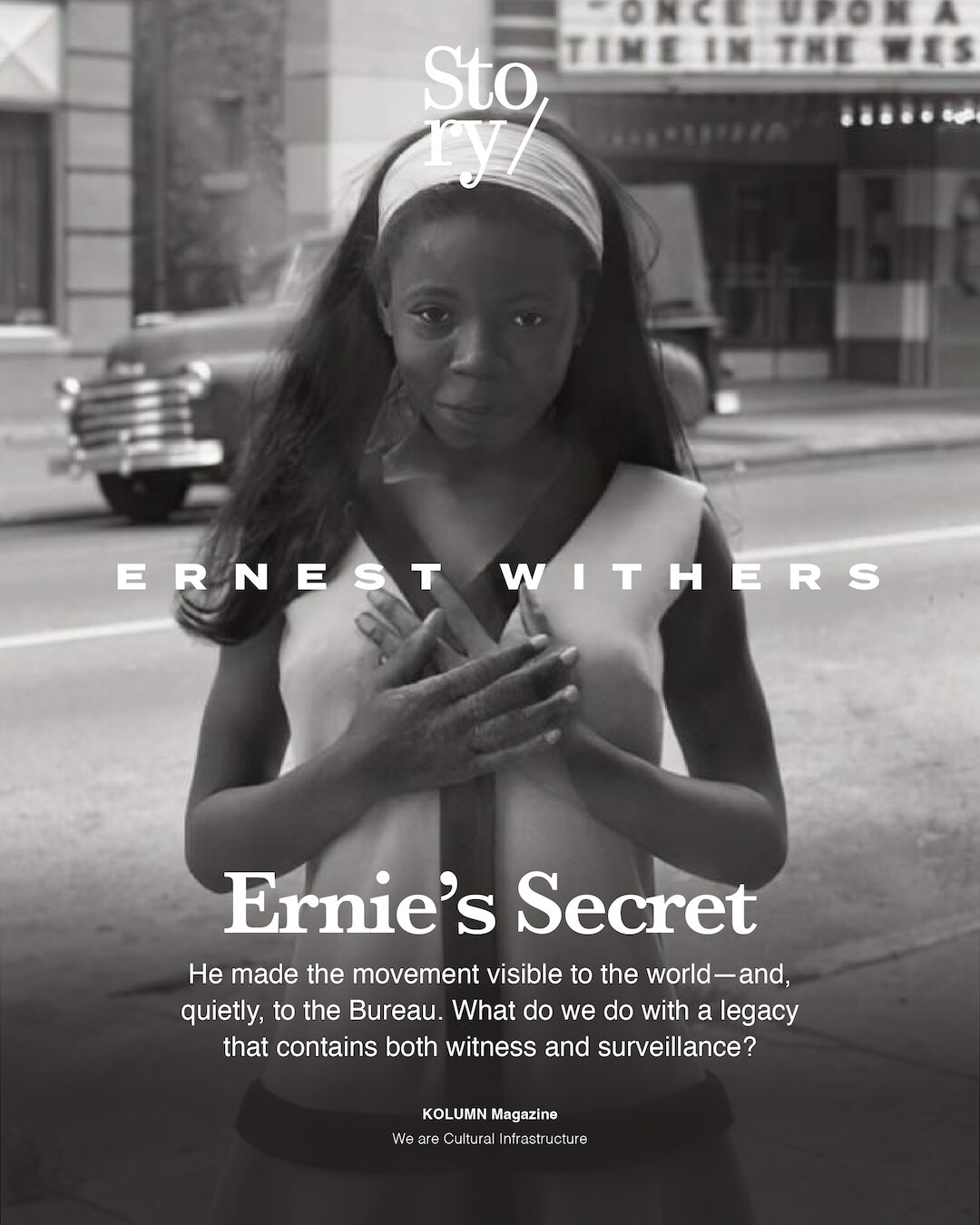

Ernie’s Secret