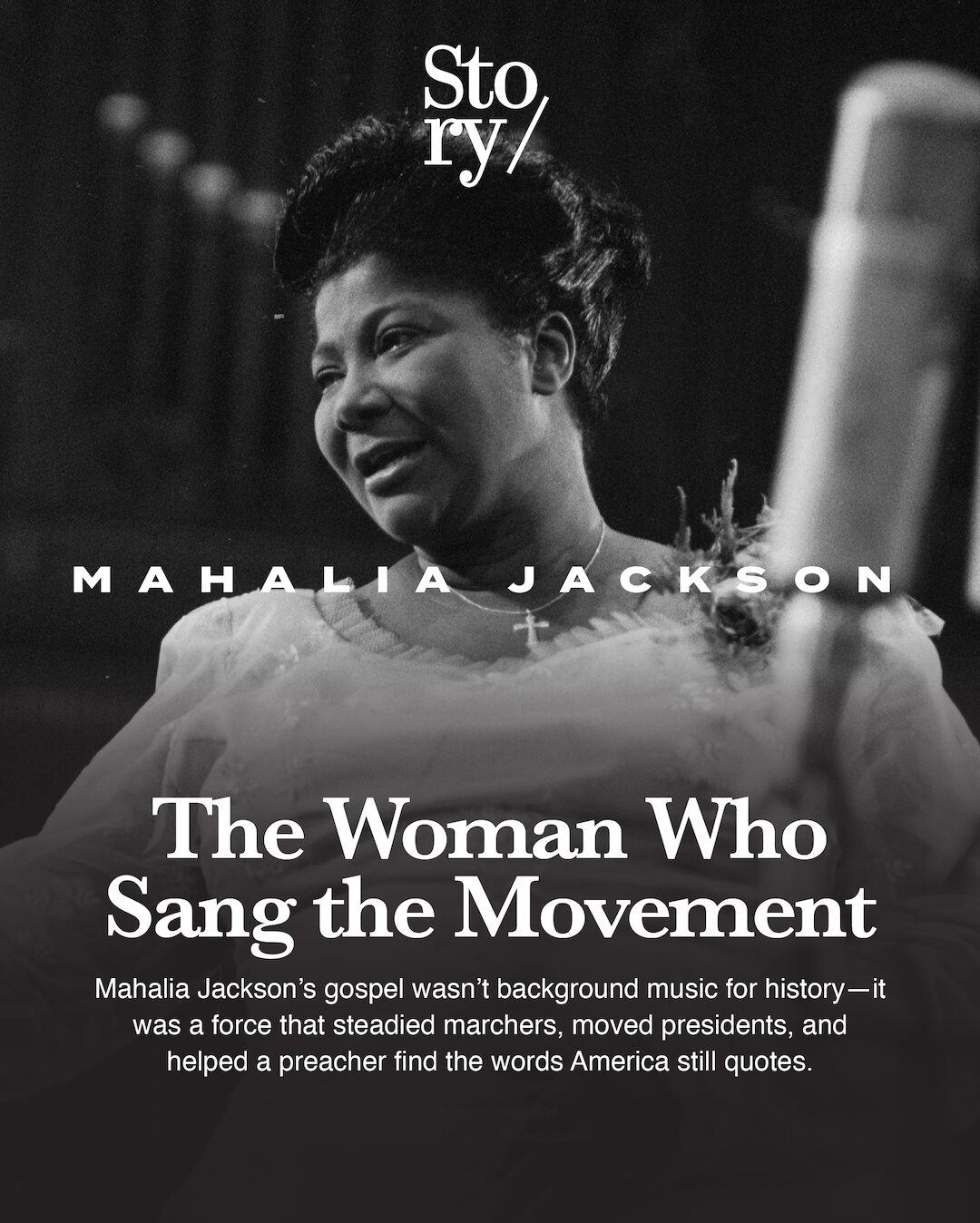

The master’s tools will never dismantle the master’s house.

The master’s tools will never dismantle the master’s house.

By KOLUMN Magazine

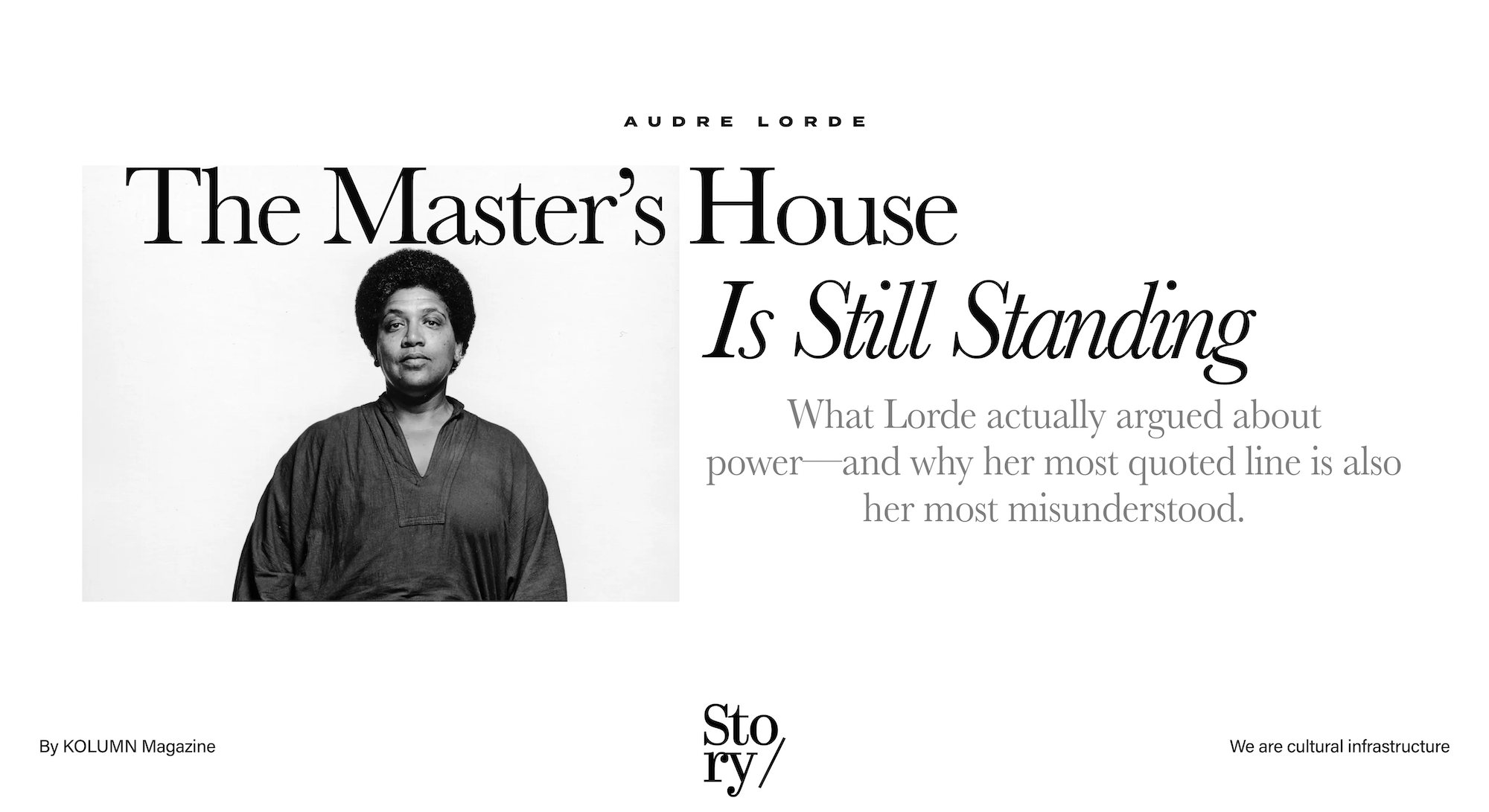

Audre Lorde did not write to decorate the world. She wrote to change its weather.

That distinction—between art as ornament and art as instrument—sits at the center of her life and legacy, and it helps explain why her sentences keep reappearing whenever public language fails. In a culture that often prizes neutrality as sophistication, Lorde treated neutrality as an alibi. In movements that sometimes prefer slogans to complexity, she insisted on specificity—about race, gender, sexuality, class, illness, and the daily negotiations required to remain a person when the world keeps trying to reduce you to a category. She is routinely introduced as a poet, an essayist, an activist. Each label fits, but none contains her. Better to begin where she began: with the insistence that she would define herself, or be defined into disappearance.

Lorde’s most enduring work functions like a tuning fork. Strike it and you can hear, immediately, whether a politics is serious. Is it willing to account for the whole human? Does it recognize that oppression is not experienced one axis at a time? Can it speak about violence without turning the harmed into symbols? Can it imagine solidarity without demanding sameness? These questions—ethical as much as strategic—run through her poems, her speeches, her teaching, her organizing, and her essays on everything from anger to erotic power to the weaponization of silence. If she has become a patron saint of contemporary “quote culture,” it is partly because she was extraordinarily quotable. It is also because she was extraordinarily precise.

What follows is an account of Lorde’s life and significance that resists the temptation to turn her into a tidy emblem. That temptation is one she warned against: the system’s “fantasies” about who you are can be as consuming as any overt attack. Her life—Harlem childhood, librarian’s discipline, poet’s ear, organizer’s impatience, patient’s frankness, teacher’s insistence—cannot be reduced to a single moral. It can, however, be understood as a coherent project: the project of making the full self politically legible, and making politics emotionally honest.

Harlem, Grenada, and the early education of an eye

Audre Lorde was born Audrey Geraldine Lorde in New York City on February 18, 1934, to parents who had immigrated from the Caribbean. Multiple biographical accounts describe her as the youngest of three daughters raised in Manhattan, in a family shaped by both the West Indian diaspora and the racial hierarchies of the United States.

Her writing returns again and again to childhood as a training ground for language: what is spoken, what is withheld, what is “proper,” what is punished. Biographers and institutional profiles note that she attended Catholic schools, an environment that sharpened her sense of discipline while also intensifying her awareness of how institutions teach certain people to doubt their own perceptions.

One of the striking details repeated across mainstream biographical sources is that Lorde published a poem in Seventeen magazine while still in high school—an early marker of both talent and determination, and a reminder that her voice arrived in public long before the culture had language for what she would become.

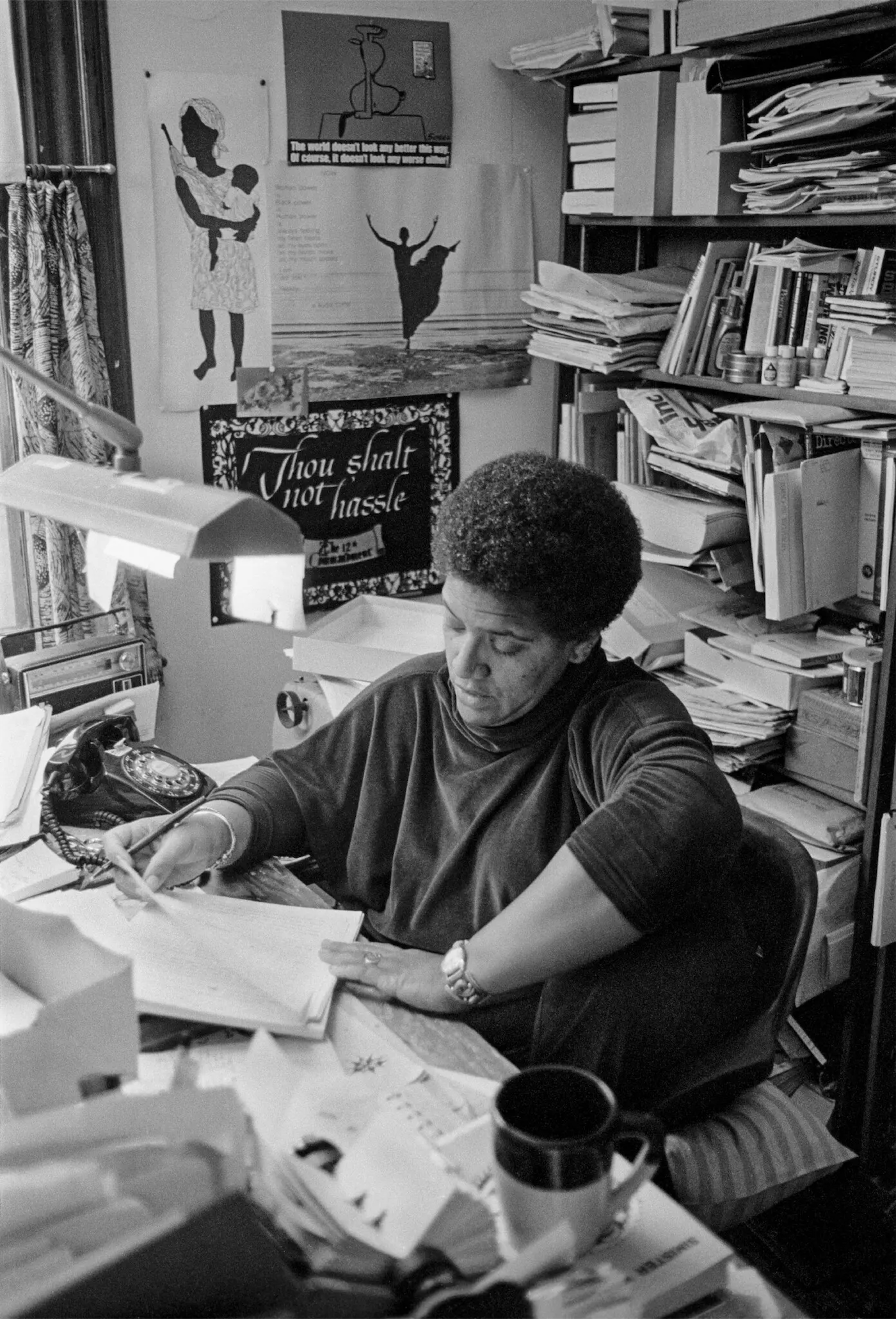

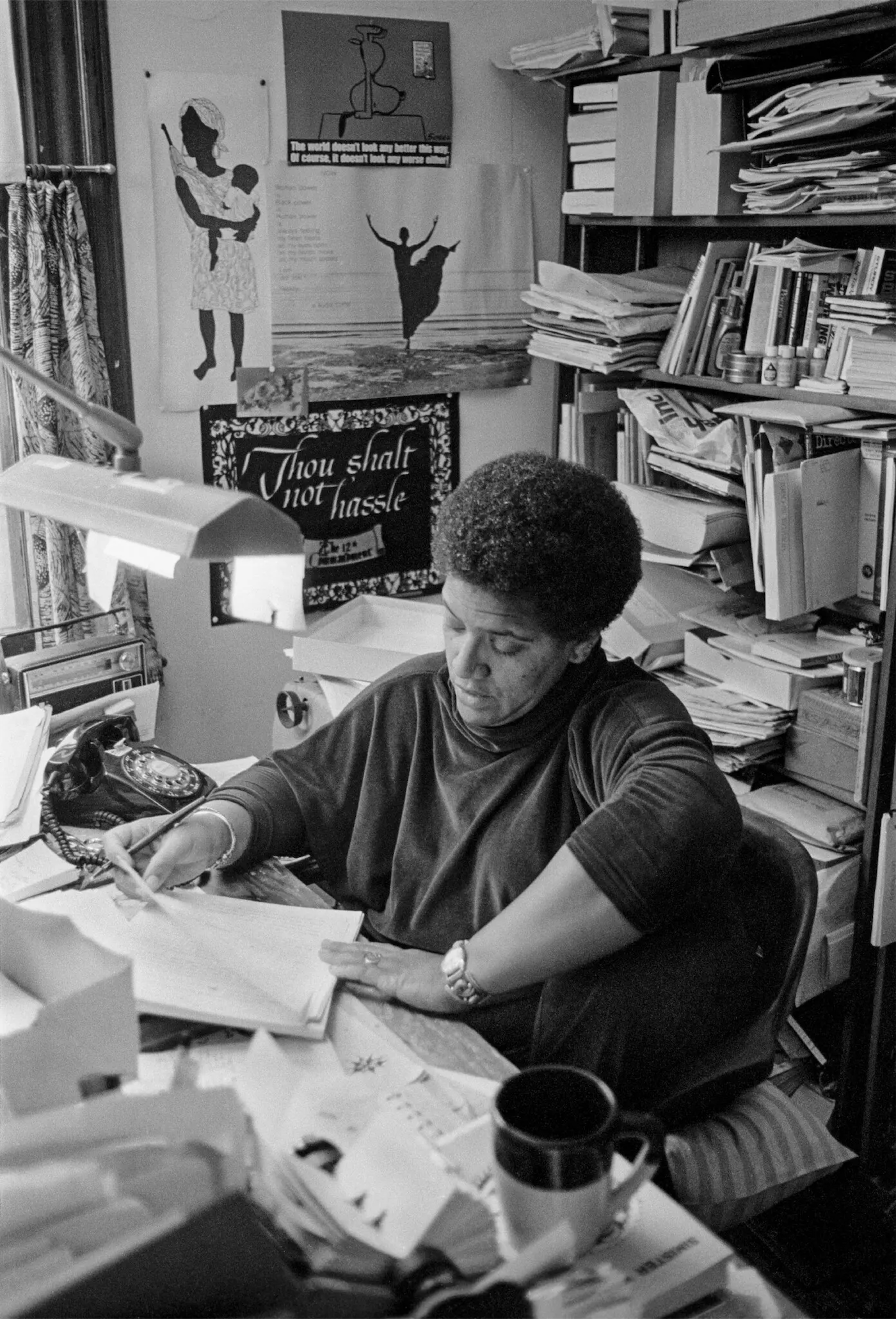

Lorde’s teenage and early adult years also reveal a pattern that would define her: she moved through institutions not as a compliant beneficiary but as a restless auditor, attentive to what those institutions made possible and what they made costly. She studied at Hunter College, later earning a master’s degree in library science from Columbia University. For years she worked as a librarian—an identity that matters more than many casual profiles suggest. Library work trained her in classification, retrieval, and the politics of access. It also placed her in daily contact with public need: who asks for information, who is denied it, who is expected to already know.

That combination—poetic intensity alongside an archivist’s sense of structure—helps explain why Lorde’s work can feel simultaneously incandescent and methodical. She did not simply emote on the page. She built arguments. She curated evidence. She returned to themes the way a researcher returns to a question that won’t let go.

A poet in the movements, not adjacent to them

It is common now to describe Lorde as “intersectional” avant la lettre. That shorthand can be useful, but it can also turn her into a precursor rather than a force. Lorde did not merely anticipate later theory; she pressured the politics of her own time, especially mainstream feminism, to stop treating race and class as secondary issues. Biographical summaries and critical introductions emphasize that her life’s work confronted racism, sexism, classism, and homophobia as mutually reinforcing systems—not separate “topics” one could schedule for later.

The politics of the 1960s and 1970s formed the air she breathed: civil rights organizing, Black cultural nationalism, anti-war activism, second-wave feminism, and the emergent energy of lesbian and gay liberation. She moved through these spaces as a participant and critic. Her writing is full of the tensions that arise when a movement’s declared values collide with its internal hierarchies—when women’s spaces reproduce racism, when Black political spaces reproduce sexism or homophobia, when liberation rhetoric makes room for everyone except the people whose lives most disrupt the “default.”

One biographical throughline is her early teaching and residency work, including a formative period at Tougaloo College in Mississippi in 1968, where she taught and engaged with Black students in the Deep South at a pivotal moment in the civil rights era. Accounts of this period describe it as artistically and politically catalytic, pushing her further toward a poetics that could carry both intimacy and anger without apology.

She later taught at institutions within the City University of New York, including John Jay College, and became part of the infrastructure that shaped generations of students who would carry her ideas forward. The emphasis here is not résumé-building but worldview. For Lorde, teaching was not separate from activism; it was one of activism’s most durable forms.

The essays that became field manuals

If Lorde’s poems provided one kind of voltage, her essays provided something else: a vocabulary for conflict inside coalition.

Her most famous line—“The master’s tools will never dismantle the master’s house”—is now invoked across contexts from academia to corporate diversity training. The risk of ubiquity is dilution. In its original setting (a speech later collected in Sister Outsider), the argument is not a decorative paradox. It is a challenge to any liberation project that adopts the values, metrics, and exclusions of the system it claims to oppose. Lorde’s point is not that strategy is futile; it is that strategy must be congruent with the freedom it seeks. Otherwise the movement becomes a renovation crew for the very house that harms it.

What made Lorde unusually effective as a political writer was her willingness to treat emotion as data. Consider her insistence that anger—particularly Black women’s anger—contains information. In a society that rewards Black women for soothing everyone else, Lorde argued that anger could clarify the terms of injustice and the shape of necessary change. Her critique was not simply that anger is valid; it was that suppressing it makes coalitions dishonest, which in turn makes them fragile. This is an ethical claim as much as a tactical one: truthfulness is not optional if the goal is liberation.

Then there is her writing on the erotic, another idea frequently flattened by misunderstanding. Lorde’s “erotic” is not a marketing euphemism for sex; it is a name for deep feeling, for embodied knowledge, for the capacity to experience joy and connection in ways that can nourish political courage. In Lorde’s hands, pleasure becomes a site of resistance, because a culture that profits from domination also profits from disconnection—people cut off from their own needs are easier to control. Here again, she refuses the split between the personal and the political, arguing that our interior lives are not private luxuries but contested terrain.

The consistency of these essays is striking. Whether she is addressing racism within feminism, homophobia within Black political spaces, or the invisibility of disabled bodies, she returns to a single proposition: difference is not a threat to coalition; the refusal to engage difference is.

“No hierarchy of oppressions,” and the discipline of coalition

Another phrase widely associated with Lorde—“There is no hierarchy of oppressions”—circulates as both insight and reprimand. In excerpted form, it has been republished and discussed for decades, often in the context of debates about whether movements should prioritize one struggle over another.

The deeper point is not that every harm is identical. It is that single-issue thinking makes people disposable: it trains organizers to bargain away someone else’s life for a simpler message. Lorde resisted that bargain because her own life refused it. She was Black and a woman and lesbian and a mother and a worker and a poet and, later, a person living with cancer. Her politics grew from the lived experience of being told—explicitly and implicitly—that there was no place where her whole self could safely stand. To accept “hierarchy” as normal would have required her to amputate herself in public. She would not.

This is where Lorde’s contribution to feminist thought becomes not simply “inclusive” but structurally transformative. She does not ask feminism to add race as a footnote; she argues that a feminism that cannot confront racism is not merely incomplete—it is functionally complicit. Similarly, a Black politics that cannot confront sexism or homophobia will reproduce domination within its own ranks. Lorde’s insistence is hard, even now, because it requires movements to examine themselves with the same rigor they apply to enemies.

The Cancer Journals and the politics of the body

In 1978, Lorde was diagnosed with breast cancer. She underwent a mastectomy and later wrote The Cancer Journals, a book that refuses the conventional script of illness narratives. Mainstream historical and literary profiles note the book’s candid engagement with mortality, fear, treatment, and the social meanings attached to women’s bodies.

The cultural expectations surrounding breast cancer at the time leaned heavily toward silence and propriety: be brave, be grateful, be “positive,” conceal what disturbs others. Lorde did not accept that script. She treated illness not as a private misfortune but as a political event, shaped by medical systems, gender norms, beauty standards, and the ways institutions manage “acceptable” suffering. In doing so, she helped lay groundwork for later feminist health activism and disability justice discourse—not by adopting abstract theory, but by telling the truth about what it costs to survive.

Years later, she learned the cancer had metastasized to her liver, a development referenced in multiple biographical accounts, and she continued to write through the progression of illness. Her later collection A Burst of Light is often cited for the now-famous framing of self-care as self-preservation—language that modern movements have embraced, sometimes as lifestyle branding, sometimes as political survival. Word In Black, The Root, and other contemporary outlets continue to reference this line precisely because it refuses the false choice between caring for oneself and caring for community.

If Lorde’s illness writing endures, it is because it does not sentimentalize the body. It insists that bodies are where history lands—through environmental exposure, medical neglect, intimate violence, labor exploitation, and the chronic stress of discrimination. The body, for Lorde, is not a metaphor. It is evidence.

Berlin and the international afterlife of her thought

Lorde’s influence is often narrated as primarily American: Harlem, New York, U.S. feminism, U.S. civil rights. But her work traveled in ways that reshaped other political landscapes, especially in Europe. Biographical accounts describe her mid-1980s teaching in Berlin and her mentorship of Black German women during the rise of what became known as the Afro-German movement.

The significance here is not merely that she “influenced” a movement abroad. It is that her framework—difference as creative force, language as resistance, coalition without erasure—proved portable. It could be translated into other contexts because it was built from structural analysis rather than parochial assumptions. Lorde’s presence in Germany, as described in biographical summaries, helped catalyze public language for Black German identity and solidarity, offering an example of how diasporic experience could be politicized without being reduced to a single national story.

St. Croix, community-building, and the later years

In the late period of her life, Lorde spent significant time in St. Croix in the U.S. Virgin Islands, where she continued writing and organizing. Biographical accounts connect this period to community-based initiatives and to her continuing commitment to Black feminist internationalism.

Lorde died on November 17, 1992, in St. Croix. The fact of her death is not the end of the story; it is the point at which her work becomes, unmistakably, an inheritance. That inheritance is both literary—poems, essays, speeches, interviews—and institutional, as organizations and archives collected and sustained her legacy.

Institutions of legacy: Archives, community health, and organizing

Some writers leave behind only texts. Lorde left behind both texts and infrastructures that continue to shape public life.

Her papers and the archival record of her work have been stewarded by institutions that understand her as more than a “writer of record.” Spelman College’s archives have been cited in public discussions of her legacy, including reporting that notes her connection to the campus and her place in Black feminist intellectual history.

In New York City, Lorde’s name lives not only in syllabi but in services. The Callen-Lorde Community Health Center, which serves LGBTQ communities, is among the institutions that memorialize her and extend her ethic—care as a public good, especially for those structurally denied it. Biographical overviews and legacy accounts also point to the Audre Lorde Project, a Brooklyn-based organization focused on LGBTQ people of color and on community organizing rooted in nonviolent activism.

These legacies matter because they answer a question Lorde implicitly posed: what does it mean for language to become material support? How does a poem become a clinic? How does an essay become an organizing model? Lorde’s work was never only about “representation.” It was about transformation—and transformation requires institutions that can outlive individual charisma.

The cultural afterlife: Why Lorde keeps returning

To talk about Lorde’s “relevance” can sound like a marketing pitch, as if her work must audition for the present. The better frame is continuity. Many of the conditions she confronted remain intact: racialized inequality, misogyny within progressive spaces, homophobia inside communities that claim to be liberatory, the commodification of feminist language, and a medical system that often treats marginalized bodies as problems rather than people. When Lorde’s lines circulate now, they do so because they name dynamics that have not gone away.

Contemporary journalism and cultural criticism continue to revisit her precisely at moments of political exhaustion. The Washington Post and The Atlantic, in reviewing new work on Lorde’s life, emphasize how biography can restore complexity to a figure too often reduced to quotations.

At the same time, Black press and Black-centered outlets keep invoking her as an ancestor of both language and strategy. The Root, for example, frames her as a figure of enduring fascination and instruction, while Word In Black’s references to her self-preservation line demonstrate how her work functions as a living resource for Black women navigating burnout, grief, and resistance.

There is also a lesson here about misreading. In the mainstream, Lorde’s “self-care” can be domesticated into spa rhetoric; her “difference” can be flattened into corporate DEI slogans; her “master’s tools” can be turned into a clever caption divorced from institutional critique. The persistence of those misreadings is itself evidence of her threat. A politics that can be commodified is often one that has been defanged. Lorde’s work remains powerful because, at its core, it resists defanging: it keeps pulling the reader back toward structural truth.

A note on Lorde and the practice of journalism

Writing about an icon invites two journalistic failures: hagiography and takedown. Lorde deserves neither. She deserves accuracy, context, and an honest account of why her work creates such loyalty and such discomfort.

The honest account is that Lorde demanded a kind of moral adulthood that many public cultures still avoid. She demanded that people acknowledge difference without fetishizing it; that they confront internalized bias without turning confession into performance; that they build coalitions without using unity as an excuse for silence. She refused the soothing story that liberation is a simple arc. Her writing insists that liberation is labor—emotional, intellectual, communal—and that it requires the courage to be seen in full.

Her insistence on speech as survival—echoed in later journalistic references to her poem “A Litany for Survival”—lands with particular force in an era when speech is both amplified and policed, when public language can be weaponized, and when silence can be dressed up as sophistication. Lorde did not romanticize speech; she understood its risks. But she also understood that forced silence is not peace. It is containment.

The significance, stated plainly

Audre Lorde’s significance is not that she was “ahead of her time,” though she often was. It is that she refused the partitioning of human life into acceptable and unacceptable parts. She wrote about Blackness without deferring to white comfort. She wrote about lesbian life without treating it as marginal. She wrote about motherhood without sanitizing it. She wrote about illness without turning it into inspiration porn. She wrote about anger without apologizing for it. She wrote about pleasure without trivializing it. She wrote about difference without turning it into a liberal slogan.

And she did so with a poet’s attention to sound and a librarian’s devotion to access: she wanted her words to be findable, usable, repeatable—tools for people who had been told they had no right to tools at all.

If her work continues to travel, it is because it offers more than critique. It offers method. It teaches how to think without abandoning feeling, how to organize without demanding self-erasure, how to survive without surrendering one’s inner life to the state, the market, or the movement. For readers and organizers alike, Lorde remains what she always was: a writer of instructions for living—sharp, unsentimental, and insistently, radically human.

More great stories

Ernie’s Secret