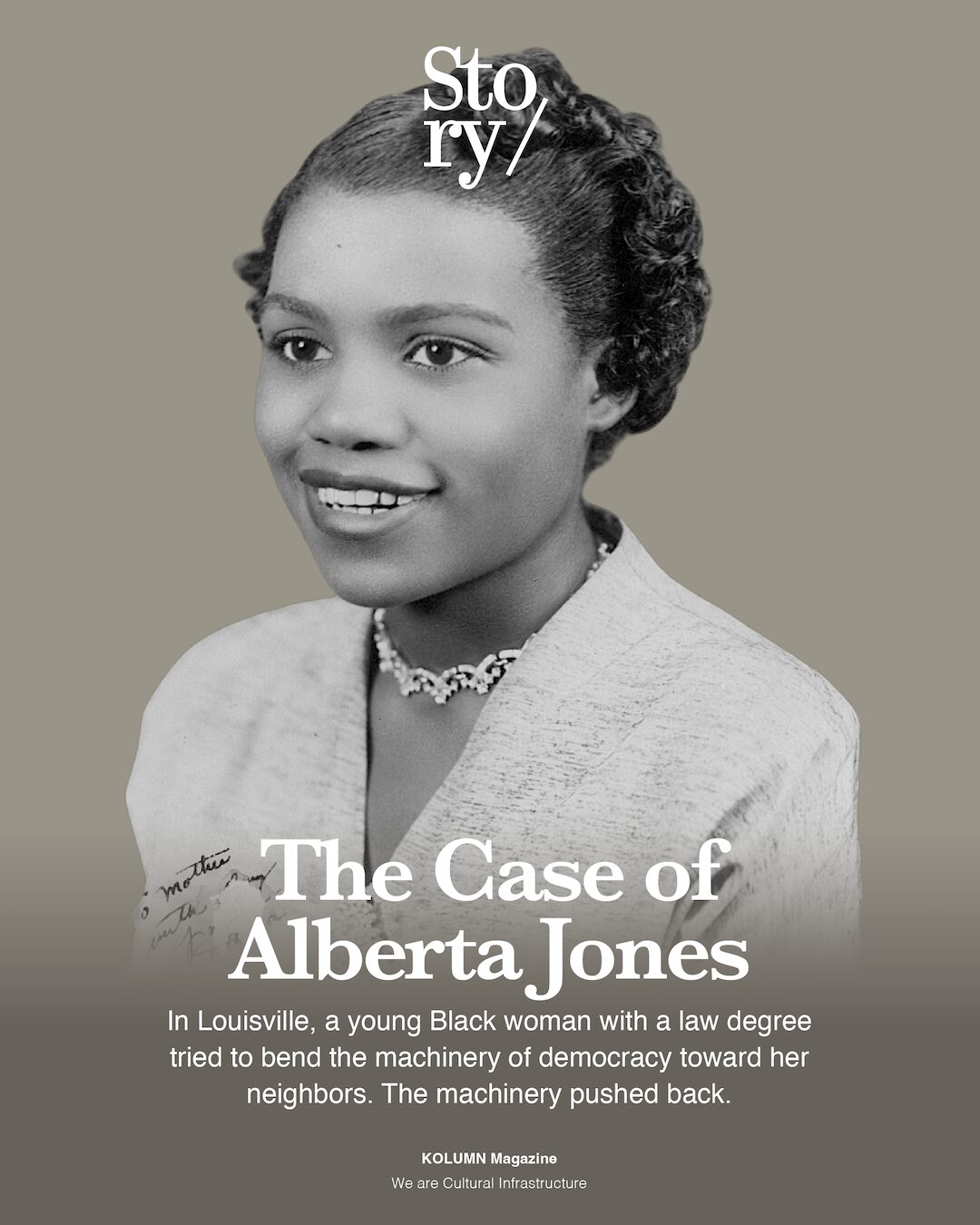

Carter emerges in the early twentieth century as a trained legal professional and organizer working at the intersections of women’s rights, Black political participation, and labor reform

Carter emerges in the early twentieth century as a trained legal professional and organizer working at the intersections of women’s rights, Black political participation, and labor reform

By KOLUMN Magazine

In the summer light of Washington, the story of American democracy often gets told as architecture. Marble steps. Doric columns. Domes that look permanent, even when the country beneath them is not. But Jeannette Carter’s life suggests another way to narrate the capital: as a city of paper, of procedures, of offices where policy becomes real because someone knows how to move a document from one desk to the next, how to certify a signature, how to write a circular that turns an abstract right into something a working woman can use.

Carter—remembered as a lawyer, labor organizer, suffragist, and political activist—belongs to a tradition that rarely receives the glamour of the great march or the famous courtroom speech. Her activism often took institutional form: a wage-earners’ association built to address Black women’s working conditions; a study club organized around party politics; publications intended to speak to women as political actors rather than as symbolic beneficiaries of reform. If the conventional suffrage story ends with ratification, Carter’s story begins there, in the uneasy reality that a constitutional amendment can be a finish line on paper and a starting gun in life.

Much of what we know about Carter comes from scattered archival descriptions, period references, and the stitching work of historians and librarians who name her in finding aids and contextual reports. A basic biographical sketch describes her as a “suffragist, journalist, attorney, [and] labor organizer,” noting she was born in 1886 and identifying her parents as Edmond Carter and Elizabeth Reeves Carter. A widely used public reference profile describes her as a Harrisburg, Pennsylvania native who studied at Howard University’s law school and built a career in Washington, D.C., including work as a pension and claim attorney.

Yet even the fundamentals require journalistic caution. An archival finding aid attributed to Howard University includes a timeline that appears to conflict with the better-corroborated outline of Carter’s education and geography—an example of how Black women’s historical records can be misfiled, conflated, or partially corrupted over time. The discrepancy is not a reason to abandon the story; it is part of the story. Carter worked in a period when Black women’s authority was routinely contested, their credentials second-guessed, their institutional footprints minimized. That the documentary record about her can itself be inconsistent is a contemporary echo of an old truth: power decides what gets preserved cleanly.

What remains consistent across sources is the arc: Carter emerges in the early twentieth century as a trained legal professional and organizer working at the intersections of women’s rights, Black political participation, and labor reform—intersections that were not merely thematic but tactical. She seems to have understood that the struggle for rights is not only about “access” but about operating capacity: the ability to read the rules, to teach them, to establish organizations that can persist, and to build media channels that can persuade.

It is tempting to frame Carter as a “first” and leave her there. She is frequently credited as the first African American woman in Washington, D.C., to become a notary—an achievement that carries symbolic weight and also hints at how much her work depended on the credibility of formal certification. But the deeper significance of her career is not the novelty of a title; it is the strategic worldview beneath it. Carter belonged to a generation that saw voting rights as a door, not a destination—and that treated the work after that door opens as the real battle.

A legal education in a city that tested it

To study law at Howard University in the early twentieth century was to join an institution that operated as both credentialing body and political workshop. Howard’s law school trained Black professionals in the language and structure of American governance at a time when that governance was explicitly designed to exclude them. Even when formal segregation statutes did not apply in the same way in Washington as they did across the South, the capital’s racial order was enforced by custom, by federal employment practices, and by the social geometry of who could move freely where.

Carter’s education, in other words, did not simply prepare her to practice; it prepared her to interpret. The tools of law—definitions, evidentiary standards, the logic of procedure—are also tools of activism when the question is how to force the state to honor its own claims. A “pension and claim attorney,” as she is often described, would be deeply familiar with the bureaucratic anatomy of the federal government: applications, proof, eligibility, timelines, denials, appeals. This is not romantic work, but it is a form of civic translation. In such work, citizenship is not a theory; it is a file that must be correct to be honored.

That background helps explain why Carter’s political activism so often leaned toward institutional design rather than one-time spectacle. It also helps explain why her presence in the suffrage movement should be understood with care. Suffrage histories have sometimes flattened Black women’s activism into supporting roles—marchers and clubwomen who “helped” a movement led elsewhere. Carter’s career suggests a different emphasis: Black women were not just supporting suffrage; they were building political literacy and organizational infrastructure to survive what came after suffrage, including the inevitable backlash.

The turn from suffrage victory to political training

In public memory, the Nineteenth Amendment is often presented as a triumphant national pivot: women win the vote, democracy expands. The reality was both more complicated and more revealing. A federal right can coexist with local obstruction. A new electorate can be both empowered and intimidated. And the meaning of political participation can be narrowed by party machines, discriminatory registration practices, employment coercion, and the everyday economics of who can afford time for politics.

One way to see Carter’s significance is through the organizations she is credited with helping establish or lead. A frequently cited example is the Women’s Wage Earners’ Association, which she helped form alongside prominent activist Mary Church Terrell and Julia F. Coleman, described as an organization advocating for Black women workers. Here, the emphasis is not merely “women’s rights” or “labor rights” but the specific compound problem of Black women’s labor—how race and gender converged in wage exploitation, job exclusion, and workplace vulnerability.

To build such an association is to acknowledge a truth that mainstream suffrage organizations sometimes treated as peripheral: that women’s political rights were inseparable from economic conditions. A woman who cannot secure stable employment, who is underpaid, or who is pushed into the most precarious labor categories may possess the vote in theory and lack power in practice. Carter’s labor organizing, then, can be read as a strategy to make the vote meaningful—not through idealism but through leverage.

This same logic appears in Carter’s approach to political education. One notable reference in a District of Columbia suffrage history report describes a “Women’s Political Study Club” founded by “attorney Jeanette Carter,” which held discussions on civics and government and maintained a reading room on Congress. Even allowing for the report’s spelling variation, the description is remarkably specific about method: reading rooms, Congressional monitoring, study as a political act. The club model suggests Carter saw citizenship as a skill that needed cultivation, especially for newly enfranchised women navigating a political landscape built to confuse, patronize, or ignore them.

This is an underappreciated theme in post-suffrage history: the work of training women to use the vote. Formal enfranchisement creates a new constituency, but it does not automatically create political confidence or procedural fluency. Carter’s clubs and publications can be read as an answer to that gap. She appears to have been building what we might now call civic infrastructure: spaces and media designed to help women convert rights into action.

The federal state and the limits of inclusion

Carter’s relationship to the federal government illustrates both possibility and constraint. She is described as having served as director of a “Colored Bureau of Industrial Housing and Transportation” under the auspices of the U.S. Department of Labor. In the World War I era, labor shortages, mass migration, and racial conflict forced federal agencies—often reluctantly—to confront Black workers’ conditions. The Department of Labor created the Division of Negro Economics in 1918 as a wartime program aimed at mobilizing and stabilizing Black labor, headed by sociologist and National Urban League leader George E. Haynes.

But even a program built to “assist” Black workers carried the era’s contradictions. A public reference account of the Division of Negro Economics describes a moment in October 1918 when the Division claimed control over the “colored section” of a housing program and Haynes removed its chief, identified as Jeannette Carter, shortly after her appointment—an episode reported contemporaneously as “one of the most peculiar cases” on record in the department.

The specifics of the internal dispute require careful handling; we should not over-narrate what the available summaries do not fully document. But the outline is telling: even within a federal initiative aimed at Black labor conditions, a Black woman professional could be abruptly displaced. This is the kind of institutional instability that shaped many Black reformers’ careers in the early twentieth century. The state offered access to titles and roles, then withdrew them under political pressure, bureaucratic infighting, or shifting priorities.

In this sense, Carter’s story is not simply one of “firsts.” It is a story about how fragile “inclusion” could be—and why activists often built parallel institutions outside the state: clubs, bureaus, magazines, civic leagues that could continue regardless of who was appointed or removed in a federal office.

The press as a political instrument

Carter’s activism extended into publication, a choice that makes particular sense in an era when Black newspapers and independent periodicals served as both information networks and movement infrastructure. According to a widely cited profile, Carter founded the Women’s Republican National Political Study Club and established a magazine called the Political Recorder and later Women’s Voice. The point is not merely that she published; it is that she chose media as a strategic lever.

A magazine aimed at women—especially in the interwar period—was not simply lifestyle content. It was a mechanism for shaping voter identity, explaining legislative stakes, and contesting the framing of women’s political participation. It also offered a platform for defining Black women’s political concerns in their own language rather than as an appendix to white women’s agendas or male-dominated party politics.

Even the titles hint at Carter’s method. Political Recorder suggests documentation: keeping track, creating an archive of governance that a reader can use. Women’s Voice suggests representation: speech, opinion, a claim to be heard in spaces that often presumed women should not lead political conversation.

The choice to link this media work to Republican women’s political study is also historically revealing. After the Nineteenth Amendment, women’s partisanship was not immediately fixed; parties competed to organize the new electorate. For Black voters, party alignment carried additional complexity. The Republican Party still held symbolic association with emancipation and Reconstruction even as its commitment to civil rights wavered across decades, and Black political strategy often involved navigating local realities rather than ideological purity.

Carter’s Republican organizing should be understood within that complexity. It was not necessarily a simple endorsement of party orthodoxy. It was a recognition that party machinery was where decisions happened—and that women needed mechanisms to engage it, influence it, and, when necessary, pressure it.

A broader movement ecosystem, seen through one career

Carter’s life becomes most legible when placed within the wider ecosystem of Black women’s organizing in Washington and beyond: club movements, anti-lynching activism, labor advocacy, and suffrage coalitions that operated simultaneously. The temptation in longform biography is to isolate a protagonist and treat her as singular. Carter was significant, but she was also part of a densely connected world of Black women who built institutions because they had learned not to trust permanence from the state.

This world included women who treated meetings as governance, who used reading rooms as political laboratories, who organized wage-earners not as charity but as a claim to economic citizenship. It included women who understood that the right to vote could be eroded by intimidation and economic dependency—and who therefore pursued a politics of self-reinforcement: build the club, publish the magazine, teach the procedure, create the network.

The District of Columbia was an especially charged setting for such work. Washington held the federal government’s symbolic center while denying its own residents full democratic participation—a contradiction that made civic education both urgent and ironic. A reading room that tracked Congress in a city without full Congressional representation is a kind of protest by method: if the system will not fully recognize you, you will nonetheless master it—and make your mastery visible.

The meaning of “activist” when activism is method

It is worth pausing on language. “Activist” can imply the street: protest, confrontation, demonstration. Carter’s activism, as the surviving record suggests, often looked like method. Her tools included credentialing (law), certification (notary work), organizational formation (associations and clubs), and messaging (publications). This is activism that understands power as procedural.

There is a reason such activism is often under-celebrated. It does not always yield a single iconic moment. It creates capacity rather than spectacle. It can look, from a distance, like administration—a word that in the American imagination is too easily mistaken for neutrality. But for Black women in Carter’s era, administration was political precisely because it was where exclusion operated: through forms, licenses, credentials, hiring rules, committee structures, and the soft power of who is allowed to be “official.”

To become the first African American woman notary in Washington, as she is commonly described, was to claim authority in a domain that depends on trust and recognition. Notaries authenticate the legitimacy of a signature; symbolically, they authenticate the legitimacy of a person’s agency in public life. That a Black woman held that role in Washington speaks to a kind of hard-won credibility—and to the stakes of maintaining it.

The question of memory, and why Carter’s story matters now

Why does Jeannette Carter matter now, beyond the satisfactions of historical recovery? Because her career answers a question that remains contemporary: what does democracy require after a right is recognized?

Modern political conversation often centers on big moments—court rulings, elections, mass mobilizations. Carter’s life reminds us that those moments are not self-executing. They demand follow-through: organizations that teach people how to use the new right, media that frames what the right is for, labor advocacy that protects the material conditions necessary for participation, and relentless attention to the system’s points of friction where rights can be quietly undermined.

Carter’s significance also lies in what her story reveals about the post-suffrage era. The victory of 1920 did not settle the question of women’s power; it reorganized it. It created new political markets, new forms of backlash, new opportunities for parties to court or contain women voters. For Black women, it unfolded under the shadow of Jim Crow, racial violence, and economic marginalization that made the vote simultaneously vital and vulnerable.

In that sense, Carter is not only a figure of “women’s history” or “Black history.” She is a figure of American governance history—someone who treated democracy as a practice requiring infrastructure, and who built that infrastructure with the tools available: legal training, clubs, bureaus, and a press designed to make women’s political voice durable.

There is also a deeper, almost philosophical contribution implied by her work. Carter’s approach suggests that political freedom is not only the absence of prohibition; it is the presence of capacity. You can be legally entitled to participate and still be practically prevented from doing so. Her organizations, by their nature, targeted that gap.

Reporting notes and unresolved threads

The record on Carter, while substantial enough to sketch a meaningful narrative, contains real gaps and inconsistencies. The most notable is the conflict between a commonly cited biographical outline (birth in Harrisburg, Pennsylvania; law study at Howard in the early 1900s) and at least one archival timeline that appears to describe a different educational path and birthplace. This does not invalidate the broader story; it underscores the need for continued archival verification, including primary documents such as enrollment records, notary commission documentation, and contemporaneous newspaper coverage of her organizational work.

Carter also appears in scholarly discussion of Black women’s voting struggles after the amendments, indicating her presence in the broader historiography even when she is not foregrounded as a central character. That kind of citation trail is often how “secondary” figures become newly visible: a footnote becomes a lead; a lead becomes a story.

What can be responsibly said now is that Jeannette Carter’s life represents a model of activism grounded in systems: a belief that rights require institutions, that political participation requires training, and that women’s voice is not a metaphor but a mechanism. In a time when democracy is again debated as fragile, Carter reads less like a recovered curiosity and more like an instruction: if you want change to last, build the structures that teach people how to hold it.

More great stories

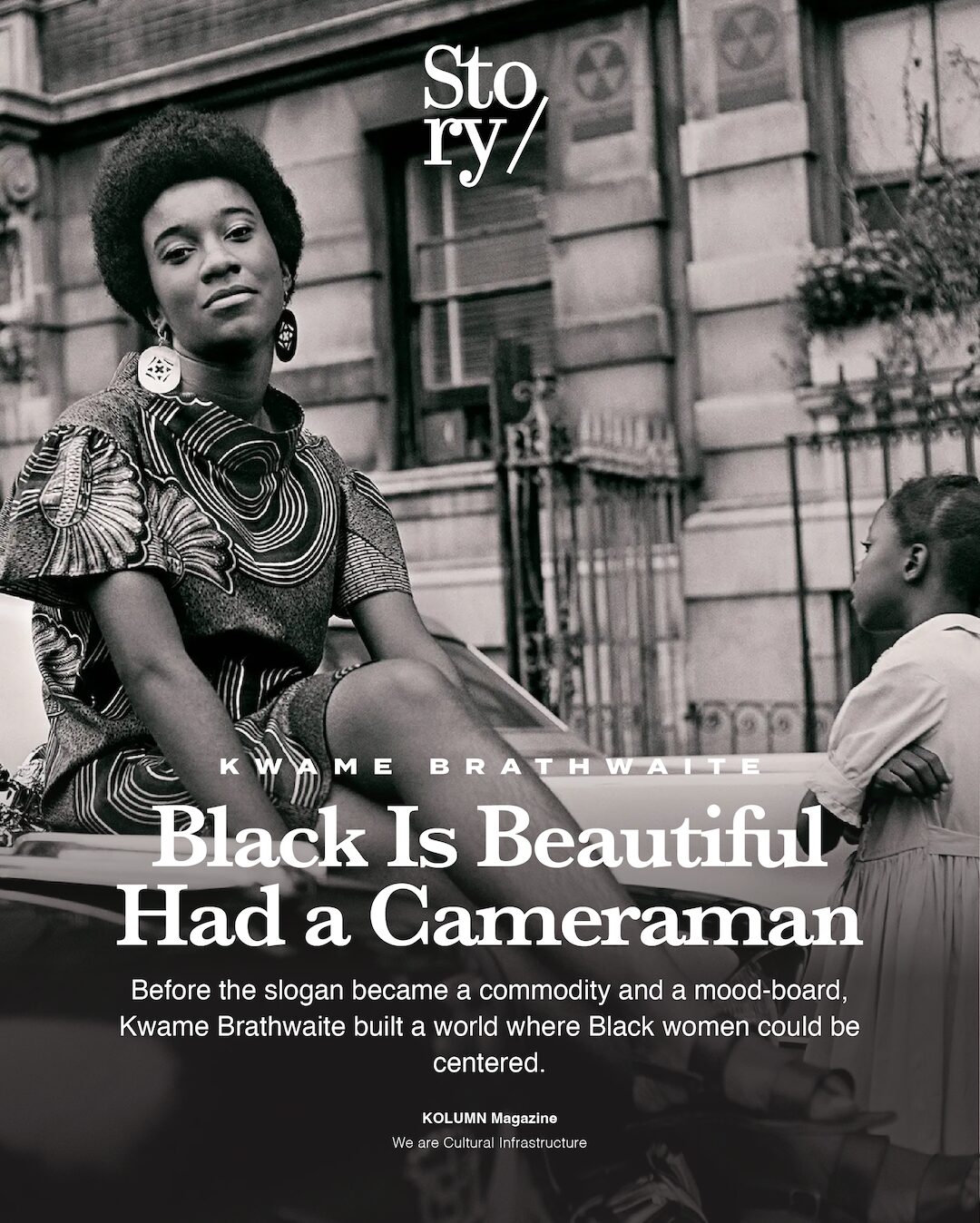

Black Is Beautiful Had a Cameraman