Bannister’s life travels a familiar American arc—migration, reinvention, self-education—yet it does so across borders and across categories that historians once treated as separate.

Bannister’s life travels a familiar American arc—migration, reinvention, self-education—yet it does so across borders and across categories that historians once treated as separate.

By KOLUMN Magazine

Edward Mitchell Bannister did not paint battle scenes. He did not make spectacle out of Black suffering, nor did he build his career on the visual shorthand white audiences often demanded from Black artists: caricature, “local color,” ethnographic distance. Instead, he painted weather and treelines, fieldpaths and marshes, twilight and surf—New England’s pastoral grammar rendered with a Barbizon hush. In the late nineteenth century, his work could pass, at a glance, as the kind of landscape painting that comforted a rising professional class: nature as moral refuge, countryside as balm. But to read Bannister only as a regional landscapist is to miss what his career reveals about American culture: how “universal” taste gets policed; how recognition can turn conditional the moment race becomes legible; how an artist can be both central in his lifetime and nearly removable afterward.

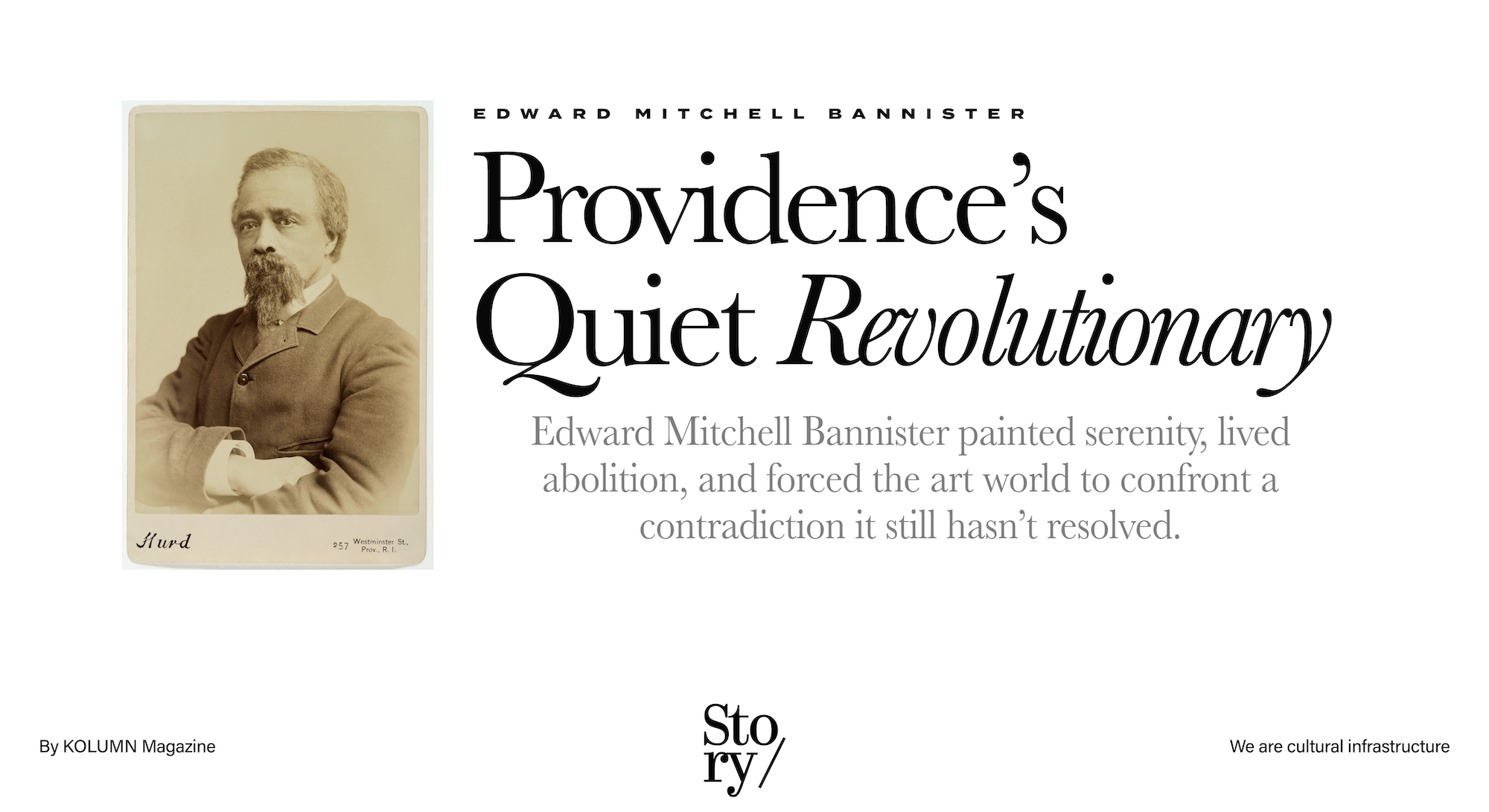

Bannister’s life travels a familiar American arc—migration, reinvention, self-education—yet it does so across borders and across categories that historians once treated as separate. He was born in 1828 in St. Andrews, New Brunswick, in the era when the British Atlantic still carried the deep aftershocks of slavery and the long improvisations of Black freedom. He made his way to Boston, a city that styled itself as abolitionist yet practiced segregation with an everyday ferocity. He married Christiana Carteaux Bannister, an entrepreneur and organizer whose own work built community institutions and financial scaffolding for Black life. In Providence, Rhode Island, he became a respected member of the Providence Art Club while maintaining ties to Black civic and religious networks. He won national acclaim in 1876 for a painting called Under the Oaks at the Philadelphia Centennial Exposition—an award that, in multiple retellings, triggered white outrage and attempted reversal once jurors learned the painter was Black.

That incident can be narrated as a single dramatic turn—triumph, backlash, vindication—but Bannister’s importance lies in what happened before and after the headline moment. He belongs to the story of Reconstruction not because he illustrated it directly, but because his career shows what Reconstruction promised and what it withheld: the possibility of Black excellence recognized on formal merit, and the persistent effort to reattach Black achievement to contingency, suspicion, and exception. His landscapes—so often read as quiet—become louder when placed against the conditions of his making: limited access to formal training, dependence on patronage, constant negotiation with a culture eager to praise art while doubting the artist.

To write about Bannister now is also to write about recovery. For decades after his death in 1901, his name faded from mainstream art histories, and his paintings circulated unevenly—collected, exhibited, sometimes admired, often detached from the full biography that made them meaningful. In recent years, exhibitions and scholarship have moved his work back into clearer view, including institutional projects that frame him explicitly as both artist and abolitionist, and new shows in Canada that insist his birthplace and early Atlantic context matter to his story.

If the point were only that Bannister overcame barriers, the narrative would be inspiring but small. The larger point is structural: Bannister’s life demonstrates how American art has used landscape—supposedly neutral, supposedly “just nature”—as a site where belonging gets asserted and withheld. The fields in Bannister’s paintings are not empty. They are contested ground, even when no one is pictured.

A boy in New Brunswick, an education made from fragments

Bannister was born Edward Mitchell Bannister on November 2, 1828, in St. Andrews, New Brunswick, near the St. Croix River. His father, Edward Bannister, was born in Barbados; his mother, Hannah, in New Brunswick, with family roots likely connected to the same Caribbean world. His father died when he was young, and his mother died when he was a teenager. In the biography that emerges from archival traces, Bannister’s early life reads as an education assembled from proximity rather than institutions: apprenticeship work, household labor, time spent copying images available in books and prints, the slow cultivation of draftsmanship through repetition.

Those details matter because Bannister would spend much of his later life insisting—sometimes in frustration, sometimes in pride—that whatever he achieved came largely without the structured training that white peers could more easily access. He was not the only Black artist of his era to face this; what distinguishes him is that he reached a level of regional prominence anyway, and did so in a genre that often functioned as the visual property of whiteness. Landscape painting, especially in the nineteenth century, helped build the myth of American nationhood: land as destiny, scenery as inheritance, the “natural” as proof of the rightful. For a Black painter to claim that genre—quietly, persistently—was a way of stepping into an argument.

Bannister left New Brunswick for Boston in the late 1840s. In the 1850 U.S. census, he and his brother appear in Boston as barbers, a profession that, within the racial caste system of the time, could offer a foothold of relative stability and social network. Yet stability did not equal access. Bannister wanted to be a painter; Boston, for all its abolitionist reputation, was also deeply segregated, and art instruction was not freely offered to a Black man with ambition.

One can imagine the daily arithmetic: time spent working to survive, time stolen for study, the cost of materials, the risk of presenting oneself in spaces that could humiliate or exclude. Bannister’s later success should not tempt us into romanticizing self-teaching as virtue. The romance of the autodidact often serves as cover for institutional failure. Bannister’s career exposes that failure and shows what it demanded from the person forced to compensate for it.

Boston: Abolitionist politics and the making of an artist’s public self

Boston in the mid-nineteenth century was both a hub of anti-slavery activism and a city where Black residents navigated discrimination in housing, employment, and public life. Bannister’s adult life begins within that contradiction. He became part of Black cultural and political communities, connected to abolitionist networks that understood culture as one front in a broader struggle.

In this environment, he also met Christiana Carteaux, a woman whose biography is inseparable from his own. Christiana was a hairdresser and businesswoman, and—crucially—she was an organizer. Their marriage did not simply provide companionship; it created a partnership in which economic strategy, social life, and political commitment braided together. For a Black artist in the nineteenth century, marriage could be a practical alliance against instability. For Bannister, Christiana’s steadiness and entrepreneurial sense helped make full-time painting conceivable.

That fact is sometimes flattened into a single line—“his wife supported him”—but support here should be understood as infrastructure. It meant space to work, time to study, protection from immediate financial crisis, and entry into networks where patrons and advocates could be cultivated. It also meant accountability: Bannister’s success was not only personal aspiration; it was part of a shared project of racial uplift, the nineteenth-century belief (sometimes strategic, sometimes burdensome) that Black excellence could serve as counterargument to white supremacist claims.

The insult that sharpened Bannister’s resolve, recorded in later scholarship and retold in modern institutional writing, came from a disparaging newspaper statement suggesting Black people could appreciate art but were “unable to produce it.” Whether Bannister encountered that line as a singular provocation or as one example among many, its logic was the air he breathed: admiration allowed, authorship denied.

If you want to understand the emotional engine of Bannister’s career, start here. He did not merely want to paint. He wanted to disprove an assertion embedded in American culture—that Black creativity could be consumptive but not generative, receptive but not originary. Landscape painting, with its association to national identity and refined taste, became his chosen arena for that contest.

Providence: The building of a career and the politics of belonging

In late 1869, Bannister and Christiana moved to Providence, Rhode Island. The relocation is often described in practical terms—new opportunities, a more stable market—but it also marks a shift in Bannister’s public identity. In Providence, he becomes not just a struggling artist but a recognized one. He opened studios in prominent buildings, exhibited regularly, and embedded himself in the Providence Art Club, an institution that mattered deeply to the city’s cultural life.

Within a few years, he was winning local recognition, including awards at Rhode Island industrial expositions, and he was increasingly associated with a Barbizon-influenced approach: tonal atmosphere, pastoral subjects, a preference for mood over drama. His paintings of fields and woods, marshes and shorelines, carried a contemplative spirituality. They were not flashy. They did not demand attention with virtuoso spectacle. They offered, instead, a kind of slow authority—composition as conviction.

At the same time, Bannister and Christiana remained anchored in Black community life in Providence. Their circle included Black clergy and civic leaders, and Christiana’s work in founding care institutions for Black elders reflected a politics of survival and dignity: building structures that the wider society refused to provide.

This double belonging—inside a predominantly white art institution, and within Black civic networks—shaped Bannister’s career. It also hints at tension. White art spaces could praise him as an individual while preferring that his politics remain invisible. Later accounts note that after Bannister’s death, memorial exhibitions emphasized his “urbanity” and painterly feeling while downplaying his abolitionist commitments—an early example of the cultural habit of sanitizing Black figures to make them easier to canonize.

To be welcomed in “artistic circles” was not the same as being fully accepted. Bannister’s life in Providence shows the difference between access and equality. He could exhibit. He could sell. He could win awards. He could also be reminded—subtly, or overtly—that his presence was conditional, his politics inconvenient, his success legible as anomaly.

1876: Under the Oaks and the moment America told on itself

The Philadelphia Centennial Exposition of 1876 was designed as a national self-portrait: a celebration of American industry, culture, and progress one hundred years after independence. For artists, it was also a major platform, a place where reputations could be made. Bannister entered a large oil painting titled Under the Oaks. It won a top prize—a first-prize bronze medal in its category—catapulting him into national notice.

Then came the backlash.

Accounts from Bannister himself and later institutional summaries describe a moment when some judges or officials, upon discovering that the award-winning painter was Black, expressed indignation and attempted to “reconsider” the prize. The details vary by retelling, but the core is consistent: the merit was acceptable until the maker’s identity violated the racial expectations of excellence. In a Washington Post feature that draws on Bannister’s own recollection, he describes pushing through a crowd where people resented his presence and commented on “this colored person” being there.

That scene is worth lingering over, because it shows how public culture works when it is confronted with Black achievement. There is a brief interval—sometimes only minutes—when the work is allowed to be simply good. Then identity becomes visible, and the system scrambles to restore hierarchy. The attempted reversal of Bannister’s medal was not only personal insult; it was cultural enforcement. It was the art world trying to reassert that excellence belonged to whiteness.

And yet, the prize held. In some retellings, other artists threatened protest if the award were rescinded; in others, the embarrassment of reversing the decision proved too costly. Bannister later remarked that he was proud the jury did not know his “antecedents, color or race” when granting the medal—an observation that reads both as satisfaction and as indictment.

It is tempting to treat this as a triumphant parable: prejudice challenged, fairness prevailing. But that would be too neat. The deeper truth is that the episode reveals the conditions under which fairness was possible: anonymity, ignorance of identity, a temporary suspension of racial knowledge. Bannister could win so long as the system could pretend he wasn’t Bannister. Once he became visible, the instinct was to undo.

This is why Bannister matters beyond the medal. He forces us to see that American cultural institutions have often preferred Black excellence as abstraction—proof that the nation is fair—while resisting Black excellence as reality, with a name and a face and a life that demands equal standing.

The art itself: Mood, method, and a Barbizon theology of the everyday

Bannister is typically described as working within the American Barbizon tradition, influenced by French painters such as Corot, Millet, and Daubigny—artists who treated rural life and landscape with seriousness and spiritual weight. Bannister absorbed this approach and translated it into New England’s environment: softer hills, coastal storms, marsh grasses, the muted gold of late afternoon.

Look closely at the recurrent features in his work: a low horizon, a sky that carries emotional force, trees that function as architecture. Often a small figure appears—walking, working, pausing—placed not as heroic protagonist but as participant in a larger rhythm. Even when the figure is absent, the land feels inhabited, shaped by labor or path or seasonal use. Bannister’s landscapes are not untouched wilderness. They are working countrysides, places where human life and natural process overlap.

This matters because landscape painting in nineteenth-century America often flirted with the myth of emptiness: land as scenic possession, available for viewing and claiming. Bannister’s work, by contrast, tends toward relationship rather than conquest. The viewer is not placed above the scene so much as within it, invited to feel weather coming, dusk thickening, wind moving across grass. The paintings ask for patience.

He also wrote and spoke about art in ways that reveal his intellectual depth. He was an autodidact who read widely—poetry, classics, English literature—and he defended artists like Millet as spiritually serious rather than merely rustic. That defense is telling: Bannister saw art as moral practice, an engagement with truth and feeling, not only surface beauty.

And yet, his style could be used against him in later histories. As modernism rose and tastes shifted toward abstraction, tonal pastoral landscapes were sometimes dismissed as conservative or sentimental. Add racism to that equation, and Bannister’s eclipse becomes overdetermined: his work fell out of fashion at the same moment institutions remained uninterested in sustaining Black artists’ legacies. Forgetting became easy.

Race and the “double bind” of Black artists in white markets

Bannister’s career also embodies a problem that would haunt later debates about Black art: the expectation that Black artists must represent Black subjects explicitly in order to be “authentic,” paired with the reality that white patronage often punished Black explicitness.

Bannister rarely painted overt scenes of Black life, especially in his mature landscape period. This absence has sometimes been read as avoidance. But it can also be read as strategy—one shaped by the cultural economy of his time. He depended on commissions and sales in a largely white market. To paint landscapes was to enter a genre that white audiences already valued, and to demand that they evaluate him on ground they claimed as neutral: beauty, technique, atmosphere.

That neutrality, of course, was itself a fiction. The landscape was never neutral. For a Black man born in the British Atlantic and working in post–Civil War New England, to paint pastoral calm could be interpreted as assimilation—or, alternatively, as a quietly radical claim: that Black presence belongs in the nation’s most “American” visual forms.

The point is not to force Bannister into a single political reading, but to recognize the constraints he navigated. He lived within what one might call an optics regime: white audiences wanted reassurance, not confrontation; Black communities wanted uplift, evidence of capacity, proof against racist claims. Bannister’s landscapes could serve both ends while also carrying his own private commitments—spiritual, aesthetic, ethical.

Christiana Carteaux Bannister: The partner history often minimizes

Any honest account of Bannister’s life must widen its lens to include Christiana. She was not merely the supportive spouse behind a male genius narrative. She was a public figure in her own right, building institutions and shaping community life in Providence. Accounts note her role in founding a home for aged Black women—an act that reads as both charitable and political, an insistence that Black elders deserved care, dignity, and permanence.

Christiana also embodied the era’s Black women’s leadership that mainstream archives routinely under-document: organizing, fundraising, creating social services, forming networks that allowed Black communities to survive amid discrimination. Bannister’s ability to paint full-time by 1870, shortly after their move to Providence, is often linked directly to her financial and emotional backing. That backing should be understood as labor—strategic, skilled, sustained.

In KOLUMN Magazine’s recent art-history coverage, the essay on Edmonia Lewis frames a similar dynamic: how nineteenth-century Black women artists operated amid scarce records, selective journalism, and the cultural urge to reduce them to emblem rather than author. That framework is useful for thinking about Christiana as well—not as footnote, but as co-architect of a life that produced art.

The long quiet after: Death, memorialization, and erasure by omission

Bannister died on January 9, 1901, reportedly of a heart attack during a prayer meeting at his church in Providence. The detail is both intimate and revealing: the artist as congregant, the end arriving in a communal spiritual space rather than in the studio myth of solitary genius.

After his death, the Providence Art Club held a memorial exhibition. The language recorded in later summaries emphasizes his gentle manner and his devotion to expressing natural scenery. It is gracious—and also selective. The memorial framing focused on Bannister’s temperament and aesthetics, leaving aside the abolitionist and civic commitments that shaped his life.

This is a common mechanism of historical sanitization: praise the art, soften the politics, and thereby make the figure safe for institutional memory. Over time, even that softened memory thinned. Bannister’s name became less common in broad narratives of American art, and his paintings—when present—were sometimes treated as regional artifacts rather than national achievements.

The erasure was not total. Works remained in collections. Archives preserved materials. The Smithsonian’s Archives of American Art holds an Edward Mitchell Bannister scrapbook spanning 1866–1901, a reminder that documentary traces survived even when public narratives faded.

But survival in archives is not the same as presence in the canon. The canon is built through repetition—textbooks, exhibitions, museum wall labels, journalism. Bannister’s relative absence from twentieth-century mainstream art history is itself part of his story: a measure of how easily Black cultural contributions can be treated as optional.

Recovery and reframing: Why Bannister is being re-seen now

Bannister’s resurgence in scholarly and institutional attention is not accidental. It aligns with broader efforts to revise American art history—efforts driven by curators, historians, and communities insisting that the story of American culture cannot remain credible if it continues to narrow itself around whiteness.

Institutions like the Smithsonian American Art Museum present Bannister’s career with explicit attention to the Centennial medal controversy and his rise despite limited formal training. The Art Canada Institute’s exhibition project frames him as “Artist and Abolitionist,” emphasizing both aesthetics and politics, and situating him within Black Canadian-American history rather than forcing him into a single national box.

More recently, Canadian institutions have mounted exhibitions that explicitly claim Bannister as part of Canada’s art history, not only America’s. The Owens Art Gallery’s “Hidden Blackness” exhibition, presented as the first major Canadian exhibition of his work, makes the point sharply: it took more than a century after his death for a Canadian institution to stage that scale of recognition.

These recoveries have a public dimension too—statues and memorials that reinsert Bannister into city space, not only museum space. That matters because erasure happens in public memory as much as in scholarly texts. When a city marks an artist as part of its identity, it also marks what kind of belonging it is willing to acknowledge.

KOLUMN Magazine’s recent coverage of institutions re-centering Black art—such as its reporting on the Studio Museum in Harlem’s renewed presence—offers a contemporary frame for Bannister’s recovery. The argument there is about place and permanence: where Black art “lives,” how institutions shape visibility, how return and rebuilding can act as cultural correction. Bannister’s story fits that logic almost too well: a major artist whose work lived in fragments until institutions chose, again, to make room.

What Bannister’s landscapes can teach us about American freedom

The obvious lesson of Bannister’s career is resilience. The deeper lesson is about the terms under which Black Americans have been asked to earn recognition.

Consider the Centennial medal episode again, not as anecdote but as microcosm. Bannister’s work was judged worthy when anonymous. Once racial identity entered the room, the institution attempted to correct what it perceived as an error. That is the logic of structural racism in cultural form: the system is willing to reward excellence only if it can keep excellence racially coded.

Bannister’s response—pride that the jury did not know his race—can be read as a complicated victory. It signals that his work met the standard. It also signals that the standard was never only about art.

In that sense, Bannister’s landscapes become documents of citizenship. They show a Black artist participating in the making of American visual culture in a genre tied to national identity. They assert, quietly but repeatedly, that the American countryside is not the private inheritance of whiteness. They place Black authorship in the business of depicting the land.

That is why his work resonates now, in a century where debates over belonging have returned with sharpened edges—over whose history counts, whose monuments stand, whose achievements remain funded, collected, taught. Bannister’s story offers a usable framework: visibility is not guaranteed by excellence; memory is not guaranteed by achievement; and institutions do not correct themselves without pressure.

The danger of turning Bannister into a symbol

There is one more ethical obligation in telling Bannister’s story: resisting the urge to convert him into a single emblem. The temptation is strong. He can be cast as the “first” this or the “only” that, a lonely pioneer proving a point. But Bannister lived among networks—Black and white, abolitionist and artistic, civic and religious. His career depended on relationships, institutions, conflicts, negotiations. To isolate him as solitary genius would replicate the same cultural habit that erases community labor and overvalues individual exceptionalism.

It is also important not to flatten his art into biography. Bannister’s landscapes deserve to be read as paintings—formal objects with compositional intelligence and atmospheric mastery—not only as evidence of racism endured. The achievement is aesthetic and technical, and it is part of why the story stings: Bannister was not rewarded out of pity. He was good.

At the same time, to insist only on aesthetics would repeat the sanitization that made him easier to forget. The honest approach holds both truths: Bannister’s art stands on its own, and the conditions under which it was allowed to stand reveal the culture’s limits.

Bannister’s place in the lineage of Black American art

When Washington Post coverage in the 1980s discussed nineteenth-century Black art exhibitions, Bannister appears alongside artists like Robert S. Duncanson, Joshua Johnson, Edmonia Lewis, and Henry Ossawa Tanner—figures who collectively demonstrate that Black American art did not begin in the Harlem Renaissance; it existed all along, often in forms that challenged what the nation claimed to be able to see.

Bannister’s specific contribution to that lineage is the way he used landscape—not portraiture, not historical tableau—as his primary field of excellence. He was, in multiple accounts, the only major African American artist of the late nineteenth century to develop his talents without European exposure, making his mastery even more striking given the era’s gatekeeping.

That fact complicates easy narratives. Many Black American artists found Europe necessary—not because America lacked beauty, but because it lacked room. Bannister built his career largely within New England, extracting possibility from a region that could admire his work while resisting his equality. His life shows that staying was also a strategy—one that required constant negotiation.

Why the storms matter

Among Bannister’s paintings, the storm scenes carry particular symbolic weight. In works held by the Smithsonian—small, intense images of squalls and darkened skies—weather becomes drama without becoming melodrama. The storm is not apocalyptic; it is part of the natural order. The light returns, or at least suggests it will.

It is hard not to see the metaphor, and yet the paintings resist being reduced to one. They are persuasive precisely because they are specific: cloud mass, wind direction, water texture, the thin glint of reflection. Bannister’s gift was to make atmosphere legible. That gift carries into his biography. He helps us see the atmosphere of his era—the racial assumptions, the institutional pressures, the conditional praise—not as abstract cruelty but as lived climate.

In 1876, a crowd resented his presence in the committee room even as his art won the prize. In the twentieth century, art history could admire the American landscape and forget the Black painter who rendered it. In the twenty-first, recovery efforts attempt to correct the record.

Bannister’s story suggests that correction is not a single act. It is a practice, repeated: collecting, exhibiting, teaching, writing, citing, placing names back where they were removed. It is, in other words, cultural work.

And Bannister—patient painter of fields, trees, and storms—belongs at the center of that work, not because he is convenient, but because his life makes the American contradiction impossible to ignore.

KOLUMN Magazine connections for readers

For readers interested in adjacent nineteenth-century recovery stories and the institutional politics of visibility, see KOLUMN Magazine’s recent essays on Edmonia Lewis and on the Studio Museum in Harlem’s renewed place-making for Black art.

More great stories

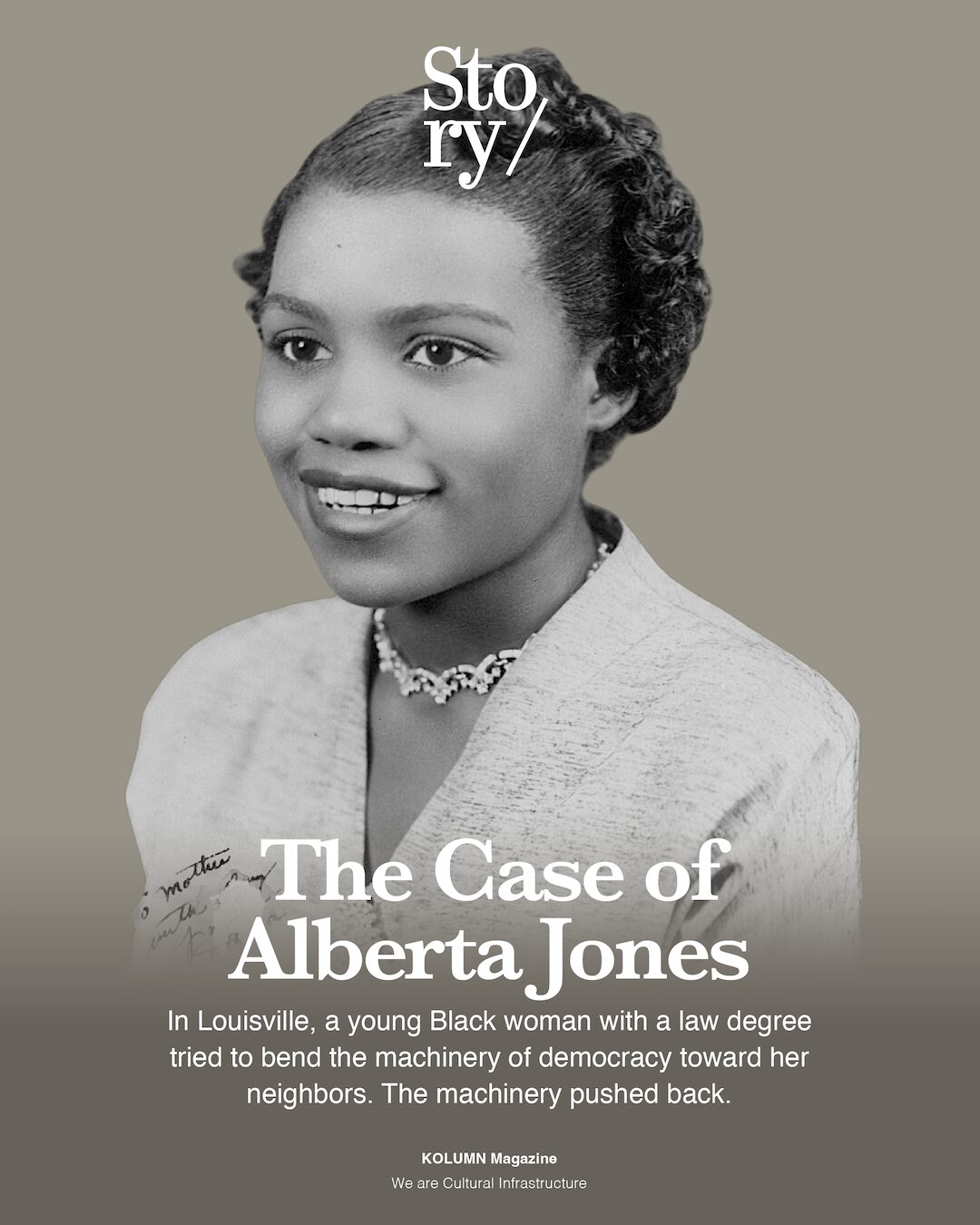

The Case of Alberta Jones