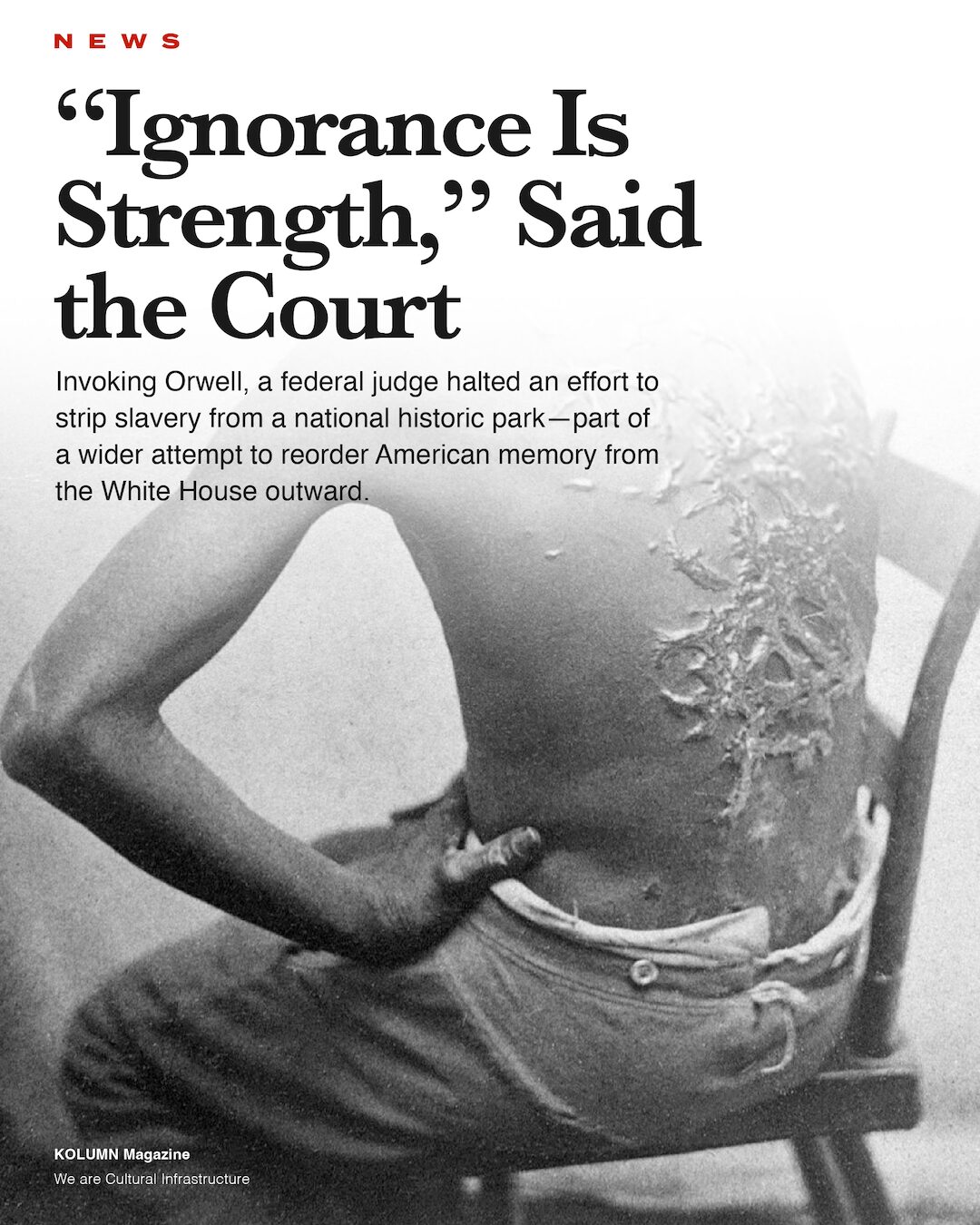

As if the Ministry of Truth in George Orwell’s 1984 now existed, with its motto “Ignorance is Strength,” this Court is now asked to determine whether the federal government has the power it claims—to dissemble and disassemble historical truths when it has some domain over historical facts. It does not.

As if the Ministry of Truth in George Orwell’s 1984 now existed, with its motto “Ignorance is Strength,” this Court is now asked to determine whether the federal government has the power it claims—to dissemble and disassemble historical truths when it has some domain over historical facts. It does not.

News

By KOLUMN Magazine

On a winter day in Philadelphia, the bricks at Independence Mall do what they have always done: they hold the line. They hold the outline of a vanished mansion, the negative space of a residence that once sat a few steps from the Liberty Bell, and the physical memory of a country learning to speak about its founding without pretending it was innocent. For years, visitors have stood at the President’s House site—where George Washington and John Adams lived when Philadelphia served as the nation’s capital—and confronted the paradox that the nation’s most famous language of freedom was spoken in earshot of human captivity.

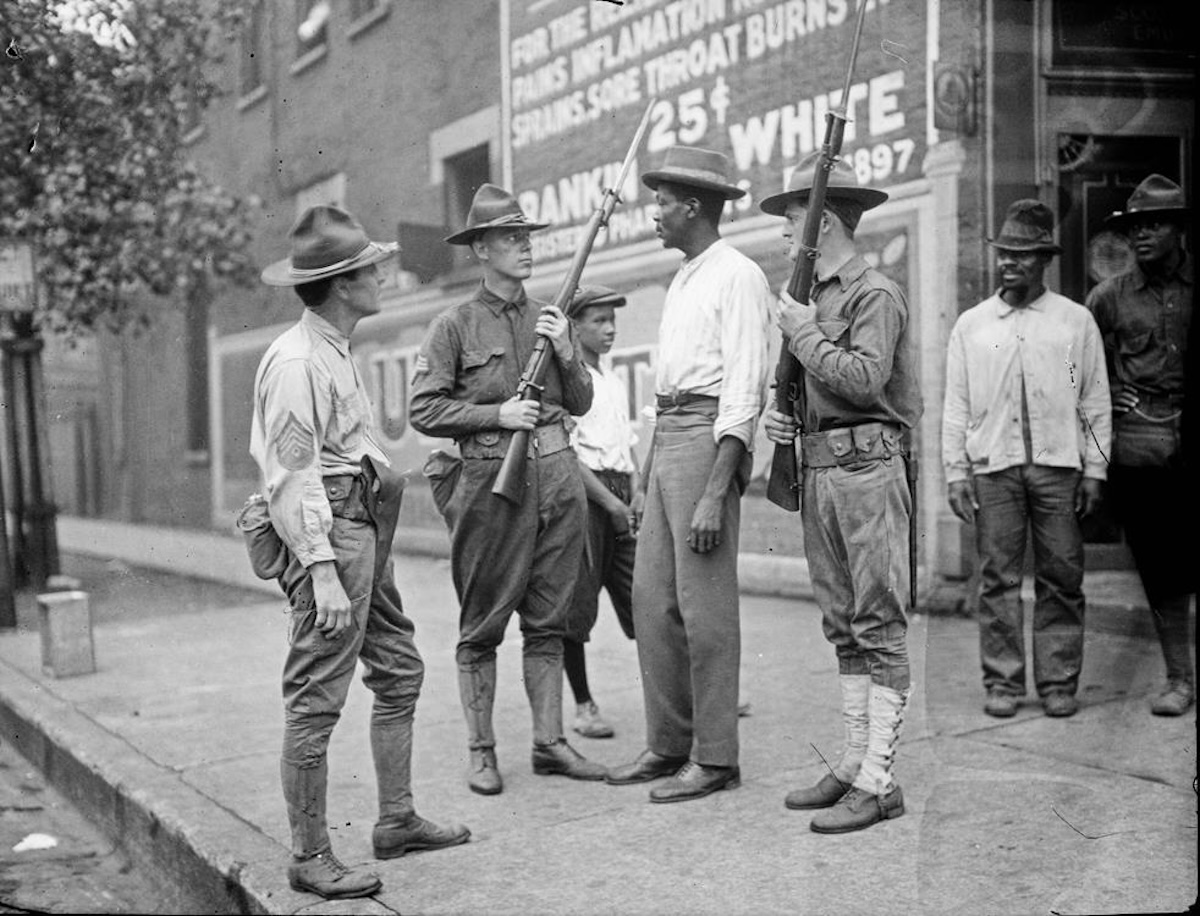

Then, on January 22, 2026, the National Park Service removed panels, displays, and video exhibits that referenced slavery and told the stories of the individuals enslaved at the President’s House. The suddenness mattered. So did the method: physical removal—panels pried off walls—turning interpretation into demolition. A city that had helped build the site, and had treated it as both memorial and lesson, sued.

On February 16, 2026, U.S. District Judge Cynthia M. Rufe granted a preliminary injunction ordering the government to reinstall what had been removed and to refrain from further changes absent mutual written agreement with the City of Philadelphia. The injunction restored the exhibit to the status quo as of January 21.

That ruling did more than settle a procedural dispute. It landed like a flare over a national argument: who gets to narrate the past when the past is inconvenient? And what happens when “patriotism” is defined as refusing to acknowledge the country’s sins?

Rufe’s opinion opened with George Orwell’s 1984, a novel that has become shorthand for state-managed reality. She wrote that the court was being asked whether the federal government had the power “to dissemble and disassemble historical truths when it has some domain over historical facts.” Her answer was blunt: it does not.

In ordinary times, a dispute over signage at a historic site might be relegated to the metro section. But these are not ordinary times for American memory. The removal at the President’s House site was tethered to a broader administrative project, formalized in a Trump executive order titled “Restoring Truth and Sanity to American History,” which framed mainstream historical scholarship and museum interpretation as “ideological indoctrination” and demanded more “uplifting” narratives at federal museums, parks, and monuments.

That project has not limited itself to Philadelphia. It has trained its attention on the Smithsonian—specifically including the National Museum of African American History and Culture (NMAAHC)—and on the curatorial idea that America’s story can be both grand and grievous, both aspirational and violent, and still worth telling in full.

The President’s House fight is the clearest recent example of an old temptation: to falsify the record by sanding down the parts that complicate national pride. It is also a reminder that the contest over history is rarely just about history. It is about power—who belongs, whose suffering counts, and which citizens are expected to accept a sanitized national identity as the price of admission.

What was removed—and why it mattered

The President’s House site is not simply a marker. It is a carefully assembled argument made in public space. Installed in 2010 after years of research and civic pressure, the exhibit told two intertwined stories: the rise of a new republic and the realities of slavery embedded inside that republic’s most celebrated households. It named the enslaved people held by Washington—Oney Judge, Austin, Christopher Sheels, Giles, Hercules Posey, Joe Richardson, Moll, Paris, and Richmond—making specific what national myth often keeps abstract.

It also placed slavery where it belongs: not in a distant plantation tableau, but at the center of federal power, within the routines of a presidential residence. It forced visitors to contend with Washington not only as commander and statesman but also as enslaver—someone who, according to the court record, rotated enslaved people in and out of Pennsylvania to evade a state law that could have enabled them to petition for freedom.

In the court’s narrative, the exhibit was the culmination of decades of intergovernmental cooperation rooted in legislation establishing Independence National Historical Park and authorizing cooperative agreements with Philadelphia—agreements that constrained unilateral alterations without mutual consent.

The removal, then, was not a mere edit. It was a rupture: of story, of governance, and of trust.

In news coverage at the time, local advocates described the takedown as cultural vandalism and an attempt to whitewash history; national outlets connected it to a broader federal effort to scrub references to racism, slavery, LGBTQ+ rights, and climate change from federal sites.

The Trump administration and Interior Department framed the effort differently: as a corrective against what the executive order called a decade-long drive to rewrite national history in a way that “disparage[s]” Americans and undermines unity. In this view, the problem is not historical inaccuracy but tone—interpretations that, by confronting atrocity, risk portraying the nation as fundamentally tainted.

That rhetorical move is central to today’s memory wars. It does not always deny slavery outright. Instead, it treats frank depiction as a form of insult, a “negative light” cast on founding principles, an unfair emphasis on “how bad” things were—as if cruelty becomes less true when it is vividly described.

The President’s House site—positioned between Independence Hall and the Liberty Bell—makes tone arguments harder to sustain. The contradiction is physically staged. Visitors can see the architecture of ideals and the architecture of bondage occupying the same civic square. The exhibit’s power comes from that proximity; so did the urgency of removing it.

The lawsuit and the judge’s injunction

Philadelphia sued under the Administrative Procedure Act, arguing that the removal constituted unlawful agency action—arbitrary and capricious—and, alternatively, ultra vires (beyond the agency’s authority).

At a January 30 hearing, the court noted, the City presented evidence; the defendants did not. A post-hearing order barred further removal or destruction pending additional court action.

By February 16, Judge Rufe granted the preliminary injunction. The practical terms were sweeping in their clarity: reinstall all panels, displays, and video exhibits that were previously in place; prevent further additions, removals, destruction, or changes unless the City and the federal defendants reach a mutual written agreement.

The opinion’s language was a rebuke not only of procedure but of premise. The court framed the case as a test of whether government, having jurisdiction over a historic site, can manipulate public memory by dismantling historical truth. It cannot, Rufe wrote, and the harms of removal included the undermining of public trust and the city’s inability to recount its story as the Semiquincentennial approaches.

In national coverage, the ruling was widely understood as a judicial check on an executive effort to reshape public history through administrative muscle. Reuters reported that the judge ordered the Park Service to reinstall the exhibit and emphasized that the federal government lacked power to alter or erase historical truths in this context.

What is striking is how quickly a local dispute became a national symbol. The legal fight was about cooperative agreements, administrative law, and agency process. The public fight was about whether slavery belongs in the nation’s official story of itself.

The deeper context: “Restoring Truth and Sanity” as a governing philosophy

The executive order that loomed over the President’s House dispute is explicit about its ambition: to “restore Federal sites dedicated to history” to “solemn and uplifting public monuments,” and to resist what it calls “ideological indoctrination or divisive narratives that distort our shared history.”

Read plainly, it is a directive about aesthetics and affect as much as facts. Its thesis is that the public past should be emotionally affirmative. Its problem is that much of American history is not.

That tension has always existed in national commemoration. But the current moment sharpens it into policy. The order’s critics—historians, civil rights advocates, museum professionals—have argued that the document’s language is a blueprint for censorship: a method for defunding or reworking exhibits that foreground racial violence, structural inequality, and contested citizenship.

The Organization of American Historians called the order far-reaching and warned it proposed to rewrite history into a glorified narrative that downplays or disappears slavery, segregation, discrimination, and division.

The National Park Conservation Association described the order as targeting interpretation itself and warned it would chill the telling of historical truth at places built to preserve it.

And in the months after the order, reporting suggested a tightening grip not only on interpretive content but on Park Service communications—rules that would centralize approval and prioritize positive portrayals, with sensitive topics treated as “high-risk.”

Philadelphia’s case gave this broader architecture a concrete face: 34 panels removed; a lawsuit filed; a judge ordering them back.

Where Christian nationalism fits—without overstating the record

The lawsuit itself was filed by the City of Philadelphia against Interior Secretary Doug Burgum and the National Park Service. The court opinion describes amicus participation by groups such as the Avenging the Ancestors Coalition and the Black Journey, and it anchors its analysis in cooperative agreements, statutes, and administrative law.

But the broader movement to demand “patriotic” history—history cleansed of racial indictment—has been strongly associated in scholarship and commentary with white Christian nationalism: a worldview that merges a particular kind of Christianity with civic identity and treats challenges to a heroic national narrative as threats to the nation’s moral legitimacy.

That connection is not speculative; it is well documented in contemporary reporting and analysis about the broader political ecosystem surrounding Trump-era cultural policy. The Atlantic, for example, has reported on charismatic Christian political movements that aim to reorder the secular state and have been aligned with Trump’s rise. And Religion News Service coverage of the President’s House controversy highlighted that religious leaders objected to the removal, in part because the exhibit referenced Black church founders such as Richard Allen and Absalom Jones—figures central to an American religious history that does not fit neatly inside triumphalist myth.

What can be said with confidence is this: the removal effort and the executive order that animated it share the same moral architecture as Christian nationalist “heritage” politics. They imagine the nation as a providential project whose legitimacy depends on an “uplifting” public story. Under that framework, slavery is not denied so much as quarantined—acknowledged only when it can be safely contained, stripped of immediacy, and prevented from complicating reverence for founders.

Philadelphia resisted that quarantine. The judge sided, at least for now, with the premise that the public interest is not served by a government-managed mood.

The exhibit as a counter-myth: Washington, Oney Judge, and the cost of specificity

The President’s House story is often told through the escape of Oney Judge, an enslaved woman who fled Washington’s household in 1796 and made her way to New Hampshire. Her story matters not only because it is dramatic, but because it disrupts the founders-as-saints narrative without requiring caricature. It presents Washington as a man who could lead a revolution for liberty while simultaneously pursuing an enslaved woman who insisted on her own.

Specificity is the enemy of sanitization. That is why names matter. It is why the wall etched with the names of the enslaved people became one of the site’s moral anchors.

And it is why removal is never neutral. When you remove “slavery” from a federal site, you are not simply editing a label. You are changing the moral temperature of the story you are telling. You are deciding which facts deserve permanence and which can be treated as optional.

The executive order’s language suggests that facts become suspect when they are emotionally unsettling. That is not a historical method; it is a branding strategy.

The Semiquincen-tennial problem: What story will the nation celebrate?

The United States is approaching its 250th anniversary, an event that will generate ceremonies, curricula, monuments, and millions of visitor encounters. In that context, federal control over museum and park interpretation is not a niche matter. It is the staging of a national self-portrait.

Judge Rufe’s opinion explicitly noted Philadelphia’s harm in being unable to recount its story in preparation for the Semiquincentennial—an acknowledgment that public history is not decoration but civic infrastructure.

Philadelphia’s President’s House site, with its literal placement beside Independence Hall, is one of the most consequential stages on which the anniversary story will be told. If slavery can be removed there, it can be removed anywhere.

This is why the case resonated beyond Pennsylvania. It was a referendum on whether the federal government can use the levers of administration to dictate a single “uplifting” national narrative—and whether cities, historians, and community coalitions have any recourse.

For now, the answer is yes: they do.

The Smithsonian front: NMAAHC in the crosshairs

The President’s House controversy cannot be separated from the Trump administration’s parallel pressure campaign against the Smithsonian Institution, in which the National Museum of African American History and Culture has been singled out as an alleged source of “divisive, race-centered ideology.”

The executive order directs federal actors to scrutinize Smithsonian content and signals that appropriations should prohibit expenditures on exhibits or programs the administration claims degrade shared American values or divide Americans based on race. PBS reported on the order’s aim to force changes at the Smithsonian by targeting funding for programs with “improper ideology.”

The reaction from historians and advocates was swift. Associated Press coverage captured the backlash, describing critics who viewed the order as an attempt to downplay the role of race, racism, and Black agency in American history. The Congressional Black Caucus issued a statement condemning the order’s effort to restrict funding based on false accusations of “divisive narratives.”

Black press and Black-led outlets framed the stakes in cultural terms: not merely a bureaucratic review, but a threat to the integrity of Black memory institutions. Word In Black warned that the executive order put the Smithsonian’s future—and the Black museum’s autonomy—at risk. Ebony reported that the order targeted Smithsonian funding and linked it to a broader attempt to reshape the public past, including talk of restoring Confederate monuments. The Root, in commentary, questioned why the African American museum was singled out in a way other iconic museums were not, reading the move as an ideological attack rather than an accountability project.

And The Atlantic, in an essayistic walk-through of what the order would mean in practice, asked a quietly devastating question: walking through the museum, which exhibits—about slavery, Reconstruction, Jim Crow, redlining, mass incarceration—would be deemed “improper ideology” by political appointees?

Even Axios reported on the swirl of allegations and denials around artifact removal, capturing the fear that political directives could translate into curatorial self-censorship.

Together, these stories map the same terrain as Philadelphia’s lawsuit. The mechanism is different—funding threats rather than crowbars—but the goal is familiar: to place boundaries around which versions of America can be officially displayed.

A pattern of attempted record-alteration

The President’s House case, the Smithsonian campaign, and broader Park Service directives fit a pattern that has repeated in American politics: when demographic and cultural shifts force a more inclusive telling of history, a counter-movement arises to restore the comfort of older myths.

Sometimes it is framed as anti-“woke.” Sometimes as anti-CRT. Sometimes as “patriotic education.” The consistent move is to treat discomfort as evidence of bias—so that the more accurate the story becomes, the more illegitimate it is said to be.

Recent commentary and reporting described the administration’s approach as a drive to reorder what museums and parks say out loud, including efforts to “scrub” federal institutions of content deemed disparaging, and to replace “divisive” language with “unifying” language.

In the President’s House litigation, the court was confronted with a distilled question: can a government, citing ideology, dismantle an exhibit that documents slavery at a presidential site? The court’s answer—at least at the preliminary injunction stage—was no.

That matters because record-alteration is rarely announced as such. It is marketed as restoration. It is justified as “truth.” It is framed as sanity.

But the court read the act of removal for what it was: a falsification by subtraction.

The civic coalition that built the site—and fought for its return

The court record and local reporting underscore that the President’s House exhibit did not emerge from a single agency’s benevolence. It was the product of years of advocacy, scholarship, and political pressure, including community stakeholders and activists.

The Avenging the Ancestors Coalition, a group involved in pushing for the site’s slavery narrative, reappears in coverage as an organizer of rallies and an amicus supporter—evidence that public history is sustained not only by institutions but by communities insisting on recognition.

The National Park Conservation Association condemned the dismantling as an insult to the memory of the enslaved people who lived at the site and warned it set a precedent of prioritizing nostalgia over truth.

In this light, the lawsuit is not simply municipal litigation. It is one expression of a broader civic reflex: when the state tries to shrink history, local coalitions expand it back.

The administration’s argument—and what it reveals

To understand the conflict fairly, it is necessary to understand the administration’s claim: that certain portrayals “disparage” Americans and that federal sites should be “uplifting.”

This claim is not new. It echoes long-standing arguments that discussions of slavery, racism, and genocide undermine national unity. What is new is the attempt to codify that argument into administrative mandates.

The executive order itself provides the logic: history sites should “remind Americans of our extraordinary heritage” and avoid narratives deemed divisive.

But uplift is not a neutral criterion. It privileges some citizens’ comfort over other citizens’ reality. It often implies that the pain of enslaved people, Indigenous people, or victims of racial terror is a secondary matter—an unfortunate subplot that must not disrupt reverence for founders or the national brand.

Philadelphia’s exhibit was designed precisely to disrupt that brand narrative—not to demean the founding, but to tell it honestly.

Judge Rufe’s opinion made room for the government to convey a different message elsewhere “if it so pleases,” but not by unlawfully changing the President’s House site without following required legal processes and consulting the City.

That phrasing is important. It suggests the court did not claim the government must adopt a single interpretive tone nationwide. It said: follow the law; honor agreements; do not treat history as a malleable script you can rewrite on command.

What this fight is really about

The President’s House site is a small patch of ground. But it is prime real estate in the symbolic economy of American identity. It sits in the tourist corridor where schoolchildren learn what a nation is.

The fight over removing “slavery” from that site is, at its core, a fight over citizenship: whether Black history is treated as a constitutive element of the United States or as an optional add-on that can be removed when it makes powerful people uncomfortable.

The Smithsonian campaign raises the same question at a national scale. NMAAHC exists because the nation once refused to place Black experience at the center of its public story. The museum is an institutional admission that the omission was itself a form of distortion. Efforts to label the museum’s content “improper ideology” are, in effect, efforts to restore the older distortion under a new slogan.

And the Christian nationalist dimension—understood as a moral framework that equates national greatness with sacred destiny—helps explain why “uplifting” becomes a mandate. If the nation is imagined as providential, then acknowledging foundational violence can feel, to adherents, like blasphemy. The solution is not better history, but quieter history.

Philadelphia refused to be quiet.

The stakes going forward

A preliminary injunction is not the end of a case. It is a guardrail while litigation continues. But guardrails matter. They can prevent temporary power from becoming permanent precedent.

The judge ordered restoration of the exhibit and prohibited further alteration absent mutual written agreement. That order preserves the possibility that public history, once built through collaboration and scholarship, cannot be undone overnight by political directive.

At the same time, the broader policy environment remains volatile. The executive order continues to shape agency behavior; Smithsonian pressure continues; and the rhetoric of “restoring truth” continues to frame scholarly consensus as propaganda.

If there is a lesson in Philadelphia, it is that the most effective defense of historical truth is not only moral argument but enforceable structure: contracts, cooperative agreements, administrative law, and courts willing to say that truth is not subject to executive convenience.

The President’s House site, once again, becomes what it has always been: a place where the nation’s ideals meet their shadow. And where the attempt to erase that shadow—in the name of sanity—reveals how fragile the official story can be when it depends on forgetting.

The bricks hold. For now.

More great stories

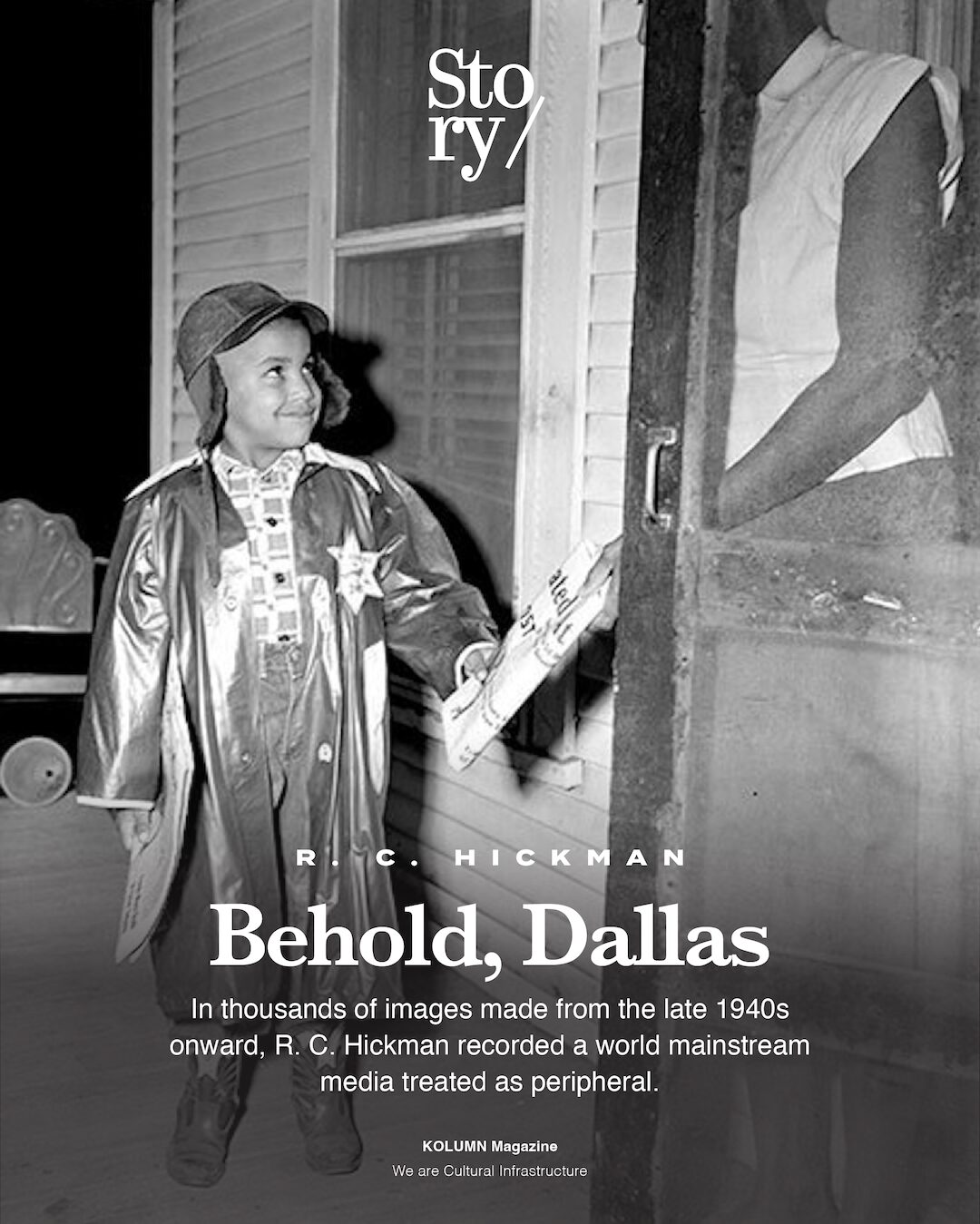

Behold, Dallas