To create an institute for Black men’s education in that moment was to reject the idea that freedom was merely the absence of chains.

To create an institute for Black men’s education in that moment was to reject the idea that freedom was merely the absence of chains.

By KOLUMN Magazine

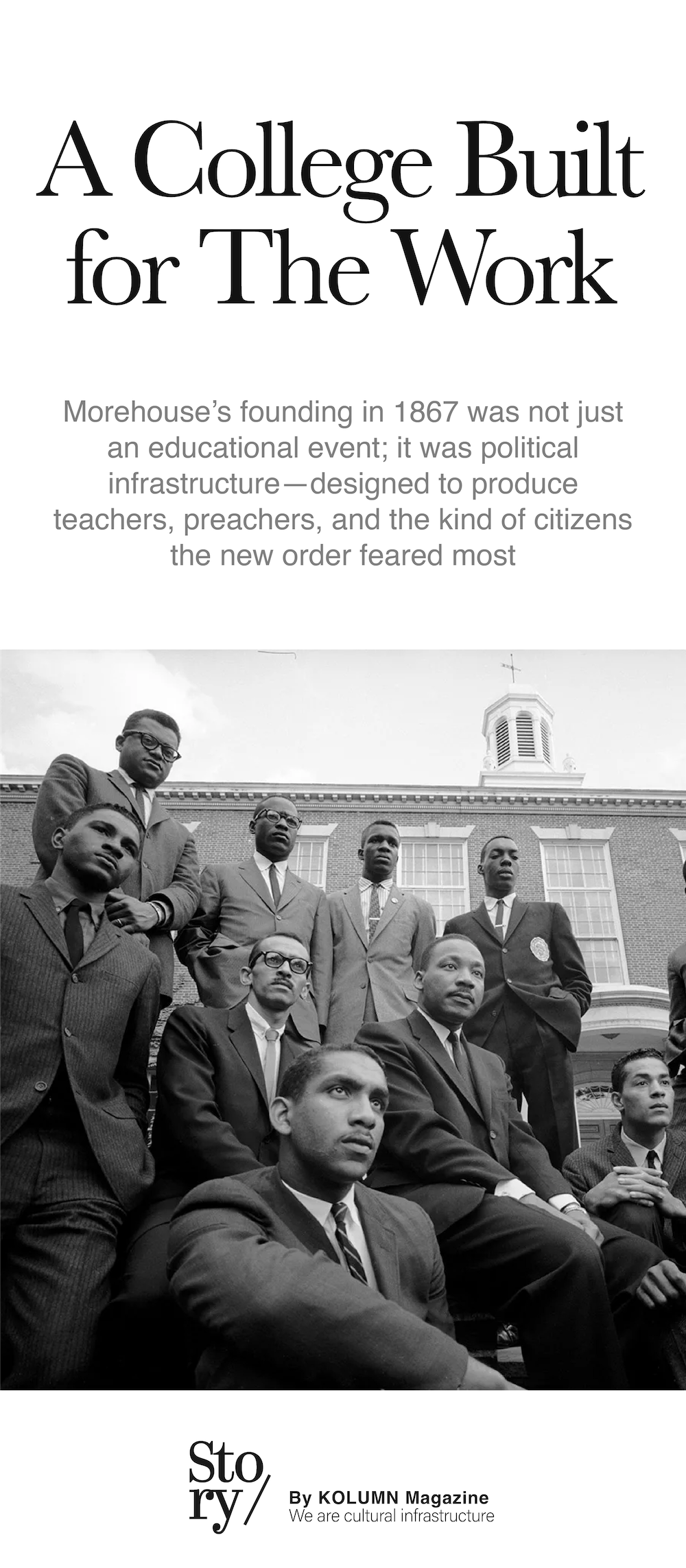

What became Morehouse did not begin as a campus or a brand. It began as a personal certainty: that education could do more than credential Black men for work. It could shape Black men for leadership—moral leadership, civic leadership, intellectual leadership—at a moment when the South was already preparing its counterrevolution. If you want a clean origin myth, you won’t find one here. The founding of the Augusta Institute was improvisational and fragile, a project stitched together from faith networks, missionary money, local urgency, and the raw fact that newly freed people needed institutions faster than the country was willing to provide them.

Yet the extraordinary thing about Morehouse is not simply that it survived. It is that it kept returning to its founding question—what should Black education be for?—and kept answering it in public, with consequences that reached far beyond its gates.

Reconstruction’s most practical dream: A school inside a church

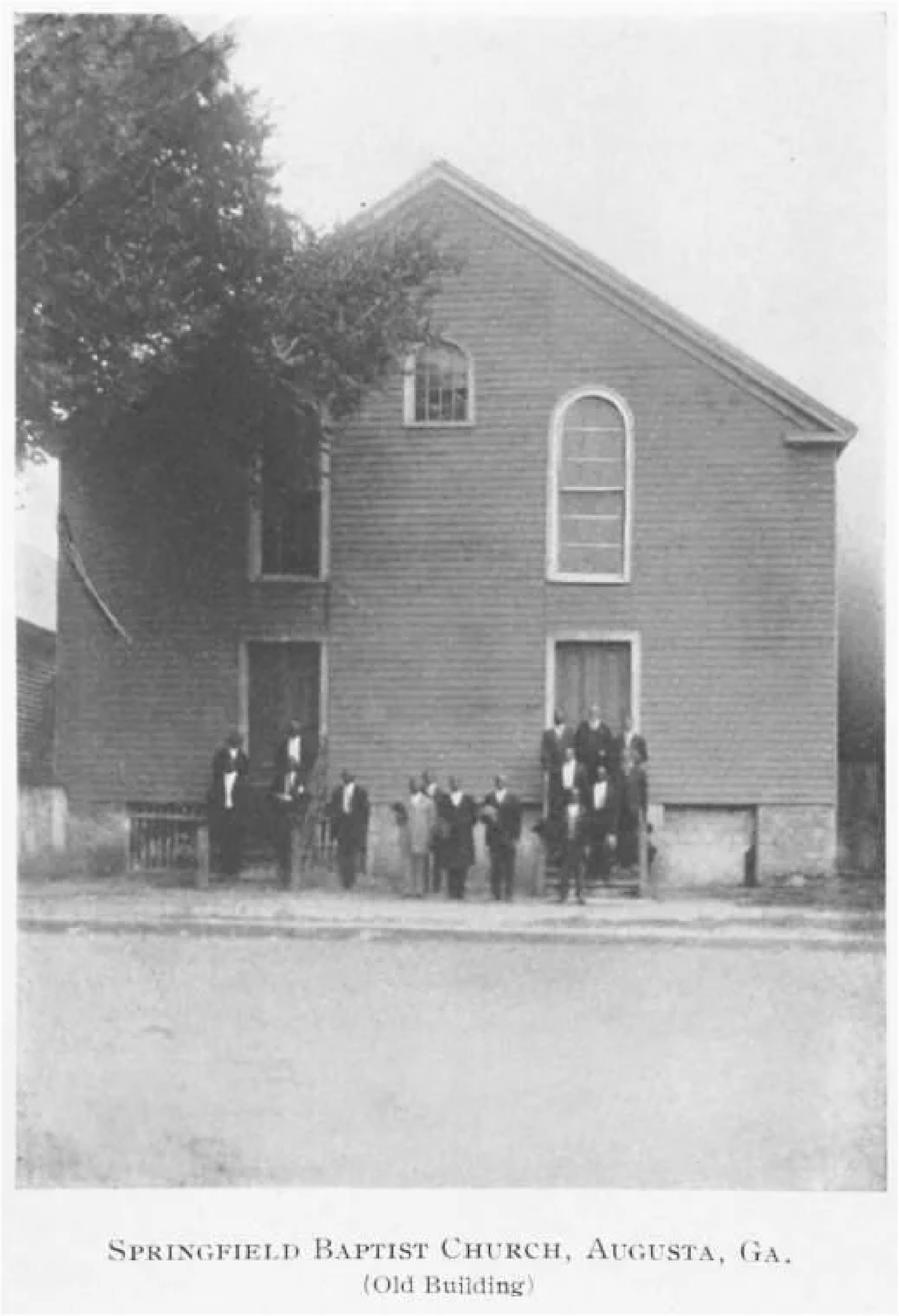

The oft-repeated detail that Morehouse was founded “in the basement of a church” can sound like a sentimental flourish. It is more accurate to read it as a blueprint. Springfield Baptist Church, in Augusta, is frequently described as the oldest independent Black church in the United States, and the historical marker commemorating the school’s birth there is explicit: in 1867, the institution that would become Morehouse was founded at Springfield as the Augusta Institute.

The choice of a church was not incidental. In Black life after emancipation, churches were among the earliest durable institutions that freed people could control. They were sites of literacy and organizing, of mutual aid, of politics when politics was dangerous. To found an institute inside a church was to align education with community authority and moral purpose, but also with community protection. A school could be attacked; a church could be attacked too, but it came with a constituency and a theology of endurance.

Morehouse’s own institutional history identifies a founding date—February 14, 1867—and names the early figures: the Rev. William Jefferson White, alongside the Rev. Richard C. Coulter and the Rev. Edmund Turney. The Georgia History marker adds texture: White founded the school “as requested” by Coulter and Turney, with Henry Watts serving as pastor at Springfield at the time, and it situates the founding as both local and networked—inside a specific congregation, linked to broader efforts to educate freedmen.

That origin—Black church governance plus external allies—foreshadows a recurring tension in the institution’s life. Historically Black colleges and universities were often built through mixed funding streams: philanthropic societies, denominational support, government assistance at times, and Black community contributions that rarely make it into official ledgers. The Augusta Institute’s earliest mission, described in multiple historical summaries, emphasized educating Black men for teaching and ministry.

This is where the founding becomes more than a timeline fact. To educate Black men for teaching and ministry in 1867 Georgia was to seed authority. Teachers and preachers were not simply service workers; they were community architects. In the Reconstruction South, Black literacy and Black political participation were treated by many white power brokers as threats requiring containment. The Guardian has argued—while discussing HBCUs in a broader historical context—that these institutions have long been targets of white supremacist hostility precisely because they represent Black advancement and organized capacity. Morehouse’s founding sits inside that reality: a school designed to expand Black capability, located in a region where the backlash to emancipation was already taking shape.

The move to Atlanta and the meaning of migration

In 1879, the institute moved from Augusta to Atlanta, to Friendship Baptist Church, and took on a new name: Atlanta Baptist Seminary. The move reads, on paper, like a logistical step. It also mirrors the internal migration patterns of Black aspiration in the postwar South: a shift toward urban centers where networks, labor markets, and political leverage could be more robust, even as violence and discrimination persisted.

Atlanta mattered as a hub of Black institution-building. It was becoming a city where Black colleges could exist in proximity, forming what would later cohere into the Atlanta University Center consortium. Morehouse’s eventual membership in that ecosystem is part of its significance, but the earlier move signals something foundational: the school was not just educating students; it was positioning itself within a geography of influence.

The name changes that followed—Atlanta Baptist Seminary, then Atlanta Baptist College (1897), then Morehouse College (1913)—are sometimes treated as rebrands. But each renaming reflects a contested question about what Black education should emphasize: theology and vocational preparation, classical liberal arts, professional training, leadership formation.

One detail about the Atlanta era is worth lingering on because it reveals how materially precarious institution-building was. A later account of the campus’s historic architecture notes that Graves Hall, constructed in the late 19th century, functioned at different times as chapel, classrooms, dormitory, lab, library, and kitchen, and that it “once housed the entire Morehouse campus” after the move from Augusta to Atlanta. The building’s multipurpose history is an architectural translation of the founding ethic: make the institution work with what you have, because the mission cannot wait for perfect conditions.

Money, patronage, and the double-edged gift

Morehouse’s history—like the history of many HBCUs—includes relationships with white philanthropic power. Wikipedia’s overview (useful as a signpost, though never sufficient alone) notes that the seminary moved to its present location in the 1880s on land associated with John D. Rockefeller, reflecting the era’s philanthropy and the American Baptist Home Mission Society’s role in supporting Black education. The broader point is not the celebrity of donors; it is the structural reality: Black institutions often had to negotiate resources through systems not designed to empower them.

This negotiation shaped Morehouse’s identity. To accept philanthropic support could be necessary for survival, but it could also invite constraints—subtle or explicit—on curriculum, governance, and public posture. The institution’s endurance required an ability to take resources while protecting mission.

That balancing act echoes in the modern era as well. Consider the national attention that followed billionaire Robert F. Smith’s 2019 announcement that he would pay off the student debt of the graduating class. The Atlantic framed Smith’s gift as not only financial relief but a kind of moral lesson about collective responsibility and the myth of purely individual success. Regardless of how one reads that moment—philanthropy as repair, philanthropy as spectacle, philanthropy as both—it underscores Morehouse’s continued role as a stage where the country works out its anxieties about race, opportunity, and what institutions owe their people.

The “first civil rights president” and the argument with America

If Morehouse began as a theological institute, it did not remain confined to theology. A major turning point came with John Hope, who became the institution’s first Black president in 1906. The New Georgia Encyclopedia describes Hope as an important educator and race leader, noting his appointment at Morehouse and later leadership at Atlanta University.

The significance of Hope is not simply that he was “first.” It’s what he represented: a philosophy that Black students deserved a rigorous academic education aimed at leadership and full civic participation. In the era’s debates, that position placed him in tension with more accommodationist frameworks that prioritized industrial training and narrowed expectations for Black citizenship. Even when those debates are summarized as personality clashes—Du Bois versus Washington, liberal arts versus vocational education—the stakes were always political. A liberally educated Black leadership class implied demands: voting rights, economic access, legal equality, cultural authority.

Morehouse’s catalog history even refers to Hope as a pioneering figure and, notably, as a “first civil rights president” in a certain framing of American higher education leadership. Whether or not one embraces that exact label, the underlying truth holds: Morehouse’s leadership increasingly positioned the institution as a generator of civic actors, not merely degree holders.

That is part of what makes the founding significant. The Augusta Institute did not set out to produce famous men. It set out to produce functional ones—teachers, ministers—who could stabilize and advance a people newly freed but not yet protected. Over time, that functional purpose expanded into a broader leadership mission, and the institution became deeply entangled with the country’s civil rights story.

Morehouse and the making of Martin Luther King Jr.

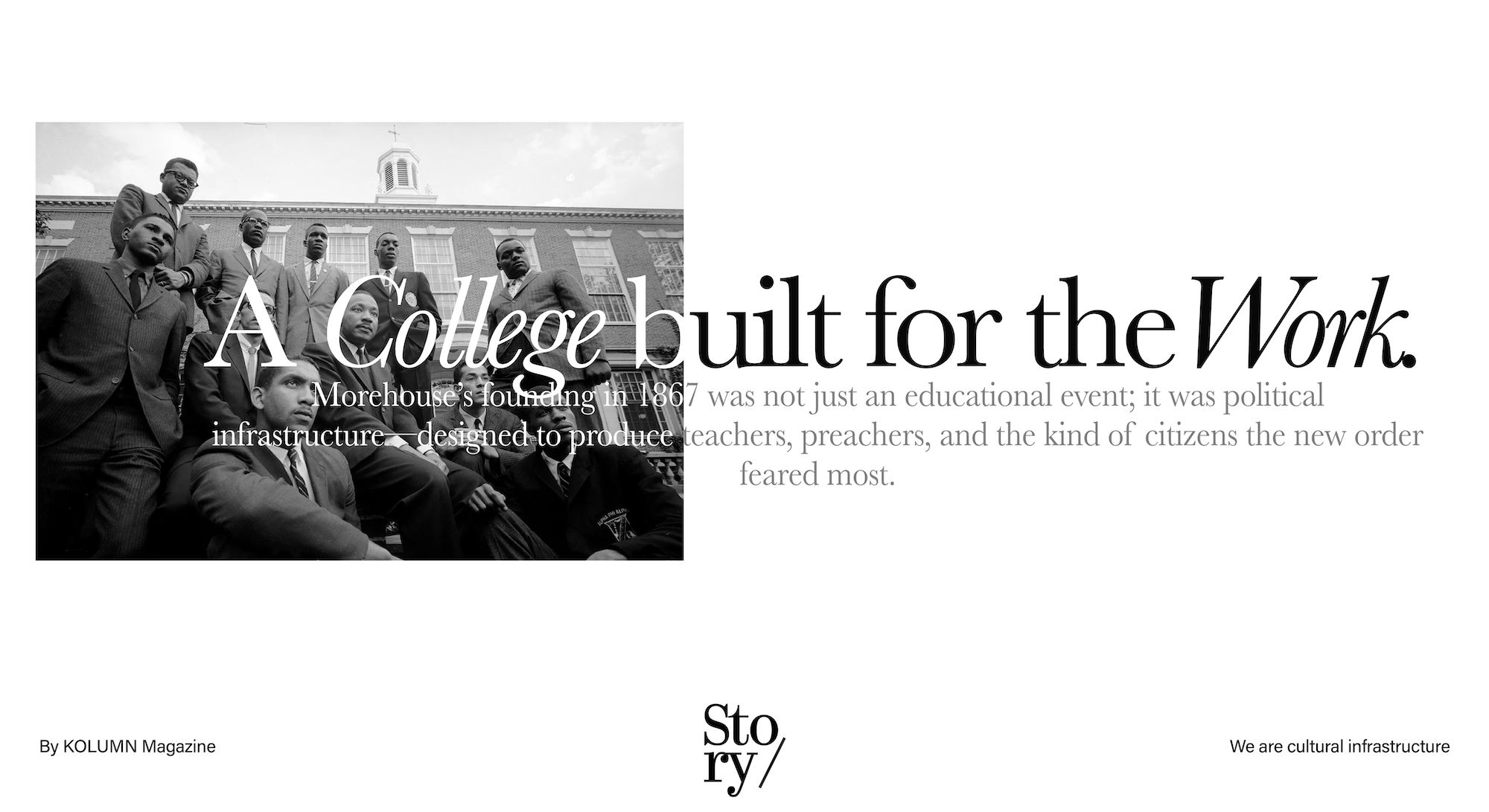

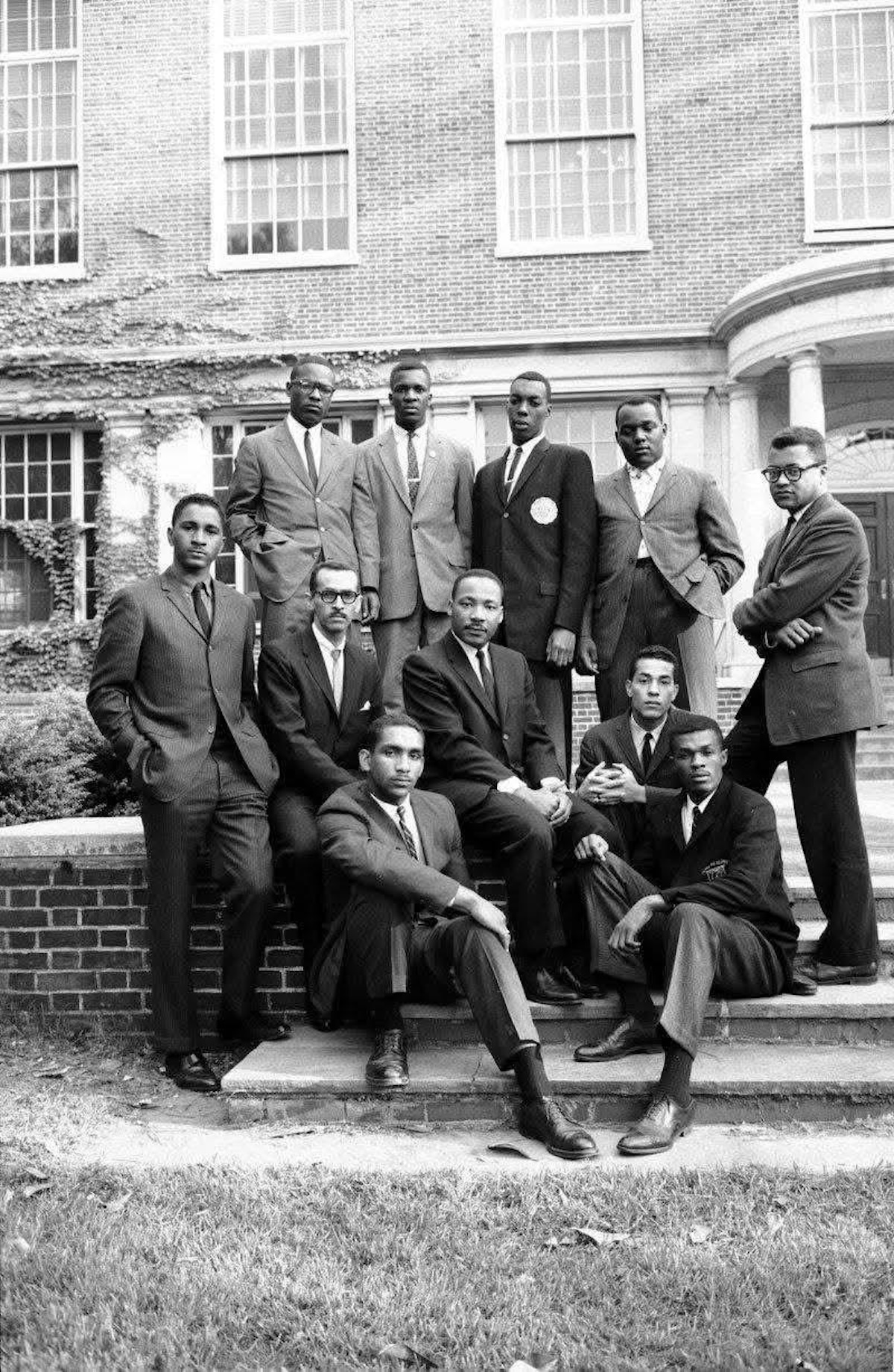

It is difficult to write about Morehouse’s significance without confronting the gravitational pull of Martin Luther King Jr., who entered the college as a teenager and for whom the institution became an early laboratory of ideas about moral responsibility and social change.

The Martin Luther King, Jr. Research and Education Institute at Stanford notes the school’s founding lineage and situates Morehouse as an institution created to educate newly freed Black men—language that ties King’s education back to the Reconstruction premise. The Atlantic has also revisited King’s Morehouse years in broader reflections on his political philosophy, noting that as an undergraduate he wrote about the purpose of education—an early indicator that his intellectual and moral formation was already underway.

What matters here is not hagiography. It is the institutional pattern. Morehouse’s significance is partially that it became a place where the idea of leadership carried moral weight. King’s eventual public theology did not materialize from nowhere; it was nurtured by environments where Black intellectual life was taken seriously, where the stakes of citizenship were discussed, and where the institution’s mission insisted that education implied service.

That mission has not been without contradictions—no institution is. Morehouse’s all-male identity, its ties to Black church traditions, and its evolving policies around gender identity have placed it in contemporary debates about inclusion and tradition. The Guardian reported on the college’s decision to admit transgender men, situating the shift within broader changes in higher education and within the particular context of HBCUs’ historic connections to churches. The point is not to treat controversy as scandal, but as evidence that the institution remains alive: it is still negotiating the relationship between tradition, identity, and the world its students must lead in.

Morehouse as a national symbol—and a working institution

Morehouse is frequently described as the nation’s only historically Black, all-male liberal arts college, a shorthand that can border on marketing. The Georgia historical marker uses similar language in naming the institution’s unique status, emphasizing its singularity. But uniqueness is not the same as significance. Significance is measured by what the institution has done, and what it has made possible.

There is the obvious roster of alumni—political leaders, artists, scholars, athletes—names that recur whenever Morehouse is invoked in public discourse. But it is also important to look at how Morehouse functions as part of an educational ecosystem, especially the Atlanta University Center, and how it adapts to modern pressures: student debt, technological change, competition for enrollment, cultural shifts, and political scrutiny.

One can see this adaptation in its recent forays into immersive and digital education. Axios reported on Morehouse’s effort to develop virtual reality courses, describing a “metaversity” model intended to engage students and expand learning formats. Whatever one thinks of the metaverse as a buzzword, the institutional logic is consistent with the founding: use available tools to keep education accessible, resonant, and future-facing.

In entrepreneurship and economic mobility efforts, Morehouse has moved aggressively to connect education to wealth-building and innovation ecosystems. The college announced Bank of America’s support for a Center for Black Entrepreneurship, framed in language that ties entrepreneurship to leadership and social impact. Morehouse’s news coverage also describes programming like STEEM that explicitly positions entrepreneurship as a vehicle for social transformation and economic mobility.

This emphasis is not a departure from the founding so much as a translation. The Augusta Institute’s early mission—train teachers and ministers—was about equipping Black men to build durable community structures. In the 21st century, economic power, venture formation, and technology fluency are also community structures. Morehouse’s significance is that it keeps updating the tools while keeping the premise.

The burden of being emblematic

To be an emblem is to be projected upon. Morehouse is frequently asked to stand in for more than itself: for Black male success, for HBCU resilience, for a certain style of leadership, sometimes even for respectability politics. The Atlantic’s essays that use Morehouse as a lens—whether on campus climate after Ferguson-era protest or on high-profile philanthropy—illustrate that the school is often treated as a national metaphor as much as a college.

That symbolic role carries costs. It can flatten internal diversity and obscure students whose lives do not match the expected narrative. It can also turn the institution into a political stage. In 2024 and 2025, the public saw this in the controversy around national political figures engaging the campus, and in the press attention that follows Morehouse leadership transitions. The Associated Press reported on Morehouse naming a new president effective in 2025, underscoring how leadership choices at the college are treated as news of national relevance, not merely campus governance. The Guardian’s coverage of disputes and protests around a presidential commencement appearance showed how quickly the institution becomes a site where national conflicts are negotiated in real time.

To say this is not to diminish Morehouse’s achievements. It is to emphasize a distinctive dimension of its significance: the school operates under the pressure of representation. It is tasked—by outsiders, sometimes by alumni, sometimes by the nation—with producing leaders who symbolize progress, even as the structural conditions for Black progress remain contested.

This is, again, a throughline from the founding. The Augusta Institute was born during a narrow window when the promise of Reconstruction was real enough to build schools, but fragile enough to be rolled back. The institution’s very existence was an argument. In different forms, it remains one.

The church basement as theory of change

The question to ask, then, is not only “What is Morehouse?” but “What kind of institution does a church basement produce?”

A basement origin story implies proximity. The school was not founded on an isolated hill or behind walls. It began embedded in community life, inside a congregation that had its own governance, its own rituals, its own obligations. It suggests an education designed to be porous—students and faculty accountable to a broader public, not only to a board or an endowment.

It also implies urgency. Basements are where people meet when the main rooms aren’t available, when the “proper” spaces have been denied. Basements are the architecture of improvisation. To found an institute there is to acknowledge that Black education in America has often had to begin before America was ready for it.

That is the deeper significance of the founding. Morehouse’s origin is not simply a date; it is a model of how Black communities have built infrastructure: through faith networks, mutual aid, strategic alliances, and relentless adaptation.

The Georgia historical marker commemorates the founding as an event worthy of public memory, not only campus memory—an acknowledgment that what began at Springfield Baptist Church became part of the state’s and nation’s educational story. Morehouse’s own timeline emphasizes that the institution’s identity evolved through movement and renaming, but that the founding core remains legible: educate Black men to lead.

Morehouse in the broader HBCU story: Survival, excellence, and the fight over value

The significance of Morehouse also lies in what it reveals about historically Black higher education in America. HBCUs have been chronically underfunded relative to predominantly white institutions, forced to do more with less, often evaluated through metrics that do not capture their full impact. Yet they continue to produce disproportionate numbers of Black professionals and civic leaders, and they serve as cultural anchors in ways that are difficult to quantify.

Ebony’s coverage of Morehouse—whether through cultural events, alumni profiles, or institutional milestones—often frames the school as a place where Black men are celebrated in a society that too often narrates Black male life through deficit. Word In Black has reported on Morehouse partnerships and initiatives that connect the institution to national development agendas and to contemporary debates about education access and student debt. These outlets help capture a truth that mainstream education coverage sometimes misses: Morehouse’s significance is not only in what it produces, but in what it protects—space for Black male intellectual formation without constant translation.

At the same time, there is no honest account of significance that ignores the pressures: student debt burdens, political attacks on diversity initiatives, cultural polarization, and the challenge of sustaining endowments and facilities. Morehouse’s modern story includes efforts to address these material constraints through partnerships and financial innovations, including philanthropic support connected to the Student Freedom Initiative and other debt-related interventions.

In other words, the founding significance is still operational. A school built to equip freed people for leadership must, in every era, confront the mechanisms that constrain that leadership: economic extraction, political suppression, cultural delegitimation. The tools change; the pattern remains.

What the founding ultimately signifies

If you return to 1867, to Springfield Baptist Church in Augusta, and imagine the world that the founders were looking at, the audacity becomes clearer. The Civil War had ended, emancipation had been declared and enforced unevenly, and the legal and social order of the South was in violent flux. To create an institute for Black men’s education in that moment was to reject the idea that freedom was merely the absence of chains. It asserted that freedom required competence, knowledge, moral grounding, and institutional continuity.

Morehouse’s founding signifies at least four things that continue to matter.

First, it signifies the central role of Black institutions in American democracy. The Augusta Institute was born because Black people and their allies understood that citizenship without education is a compromised citizenship.

Second, it signifies the church as an engine of Black public life. Even as Black America diversified religiously and culturally, the historical role of churches in institution-building remains a crucial part of the story, and Morehouse is one of the clearest educational artifacts of that tradition.

Third, it signifies adaptability as a survival skill. The move to Atlanta, the name changes, the shifting curriculum emphases, the expansions into new modes of teaching—these are not distractions from the mission. They are what it looks like to keep a mission alive across eras.

Fourth, it signifies a particular theory of leadership: that education should produce men who understand their lives as public instruments, accountable to community. This is why the institution keeps appearing in the nation’s moral conversations—civil rights, gender and inclusion, economic justice, technology and access. It is not that Morehouse is always right. It is that Morehouse is structurally positioned to be consequential.

The founding of the Augusta Institute is therefore not simply the beginning of a college. It is a case study in how Black freedom was—and is—constructed: through institutions capable of outlasting backlash, training people not only for jobs but for responsibility, and insisting that the country’s democratic claims must be made real in the lives of those it once excluded.

Morehouse started in a basement because, in 1867, a basement was the space available. The significance is that the founders built anyway—and that the institution has spent more than a century proving that the place you start does not have to determine the scale of what you can change.

More great stories

Frederick Douglass: The Day He Gave Himself