Hines moved as though the tapping itself was the plot, the punctuation, the confession.

Hines moved as though the tapping itself was the plot, the punctuation, the confession.

By KOLUMN Magazine

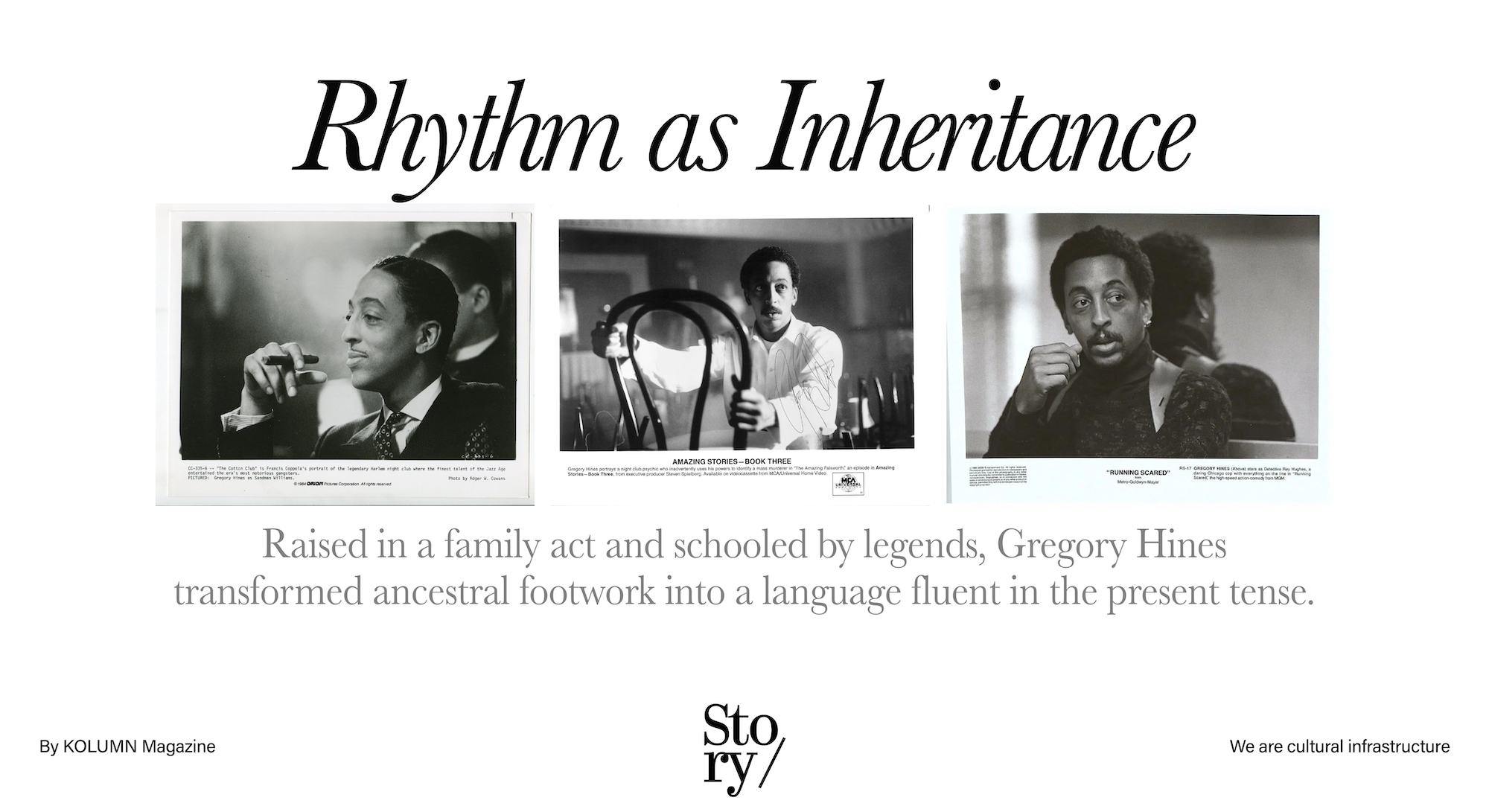

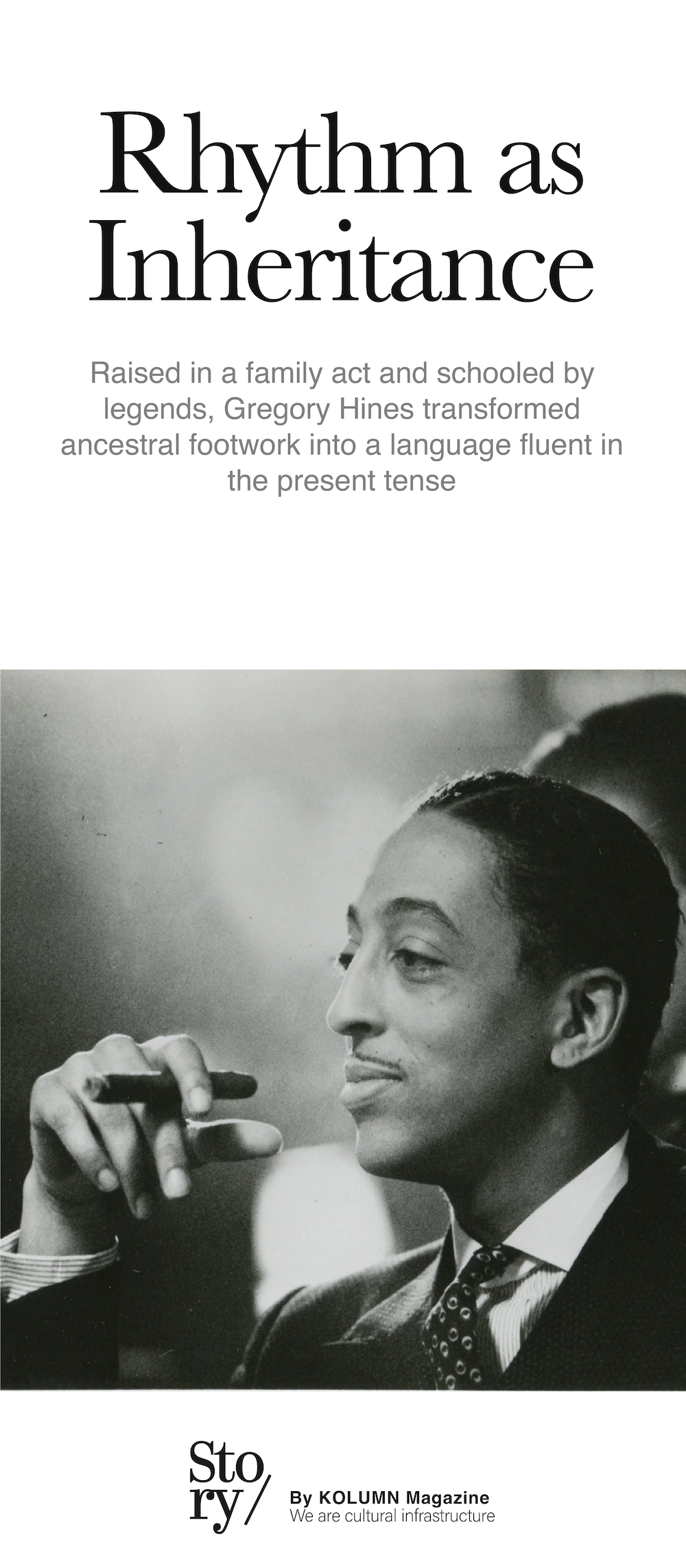

The first thing you notice about Gregory Hines—on film, on stage, in photographs frozen midair—is not simply the virtuosity. It’s the argument he seems to be making with his whole body. Tap, in lesser hands, can become decoration: a bright perimeter around the “real” performance, a specialty act delivered between plot points. Hines moved as though the tapping itself was the plot, the punctuation, the confession. His sound was not dainty. Critics reached for words like “earthy” and “roughhewn,” a way of describing a dancer who didn’t hide the labor or soften the edges, who made rhythm feel like work and joy at the same time.

That quality—muscular clarity, the refusal to treat an American vernacular form as museum material—helps explain why Hines remains so central to tap’s late-20th-century revival. It also explains the strange breadth of his fame. He was a Broadway leading man and a Hollywood actor; a singer and a choreographer; a primetime presence and a documentary host; a student of elders and a mentor to the young; an artist who could share a bill with legends and still insist the next generation deserved the spotlight.

To understand his significance is to see how rarely American entertainment produces someone who can operate as both star and steward. Hines lived in that dual role. He wanted applause, yes, but he also wanted continuity. Tap had given him a life; he returned the favor by giving tap a future.

A child of the circuit

Gregory Oliver Hines was born in 1946 in New York City, into a world where talent could be inheritance and where the stage could be family business. He began dancing as a toddler, and by childhood he was already performing professionally alongside his brother, Maurice—two boys moving with the poise and velocity of people who understood that timing is not only musical, but also economic.

Their training and apprenticeship were not abstract. This was a lineage-based education, the kind that happens in rehearsal rooms and back corridors, under teachers who know the tradition because they lived it. The brothers studied with celebrated choreographer Henry LeTang, a name that appears like a watermark through mid-century American dance history, connecting nightclub stages, Broadway, and the deep ecosystem of Black performance in New York.

As boys, the Hines brothers learned the core paradox of tap: it is both intensely individual and inseparably communal. A tapper develops a personal sound—the signature of how heel and toe strike the floor, how weight shifts, how the body “speaks.” But tap also depends on call-and-response, on trading phrases, on listening as much as executing. From the beginning, Hines was shaped by the duet form: brother to brother, dancer to drummer, soloist to band, modern artist to ancestral tradition.

When their father joined their act as a drummer, the family became a single unit on stage, eventually performing under the name “Hines, Hines and Dad,” a title that reads like vaudeville and sounds like an entire era of American show business.

That early structure—family rhythm, professional discipline, public performance—produced in Hines a comfort with audiences that never seemed manufactured. It also produced a hunger: the sense that the stage was not merely where you proved yourself, but where you belonged.

Tap as language, not ornament

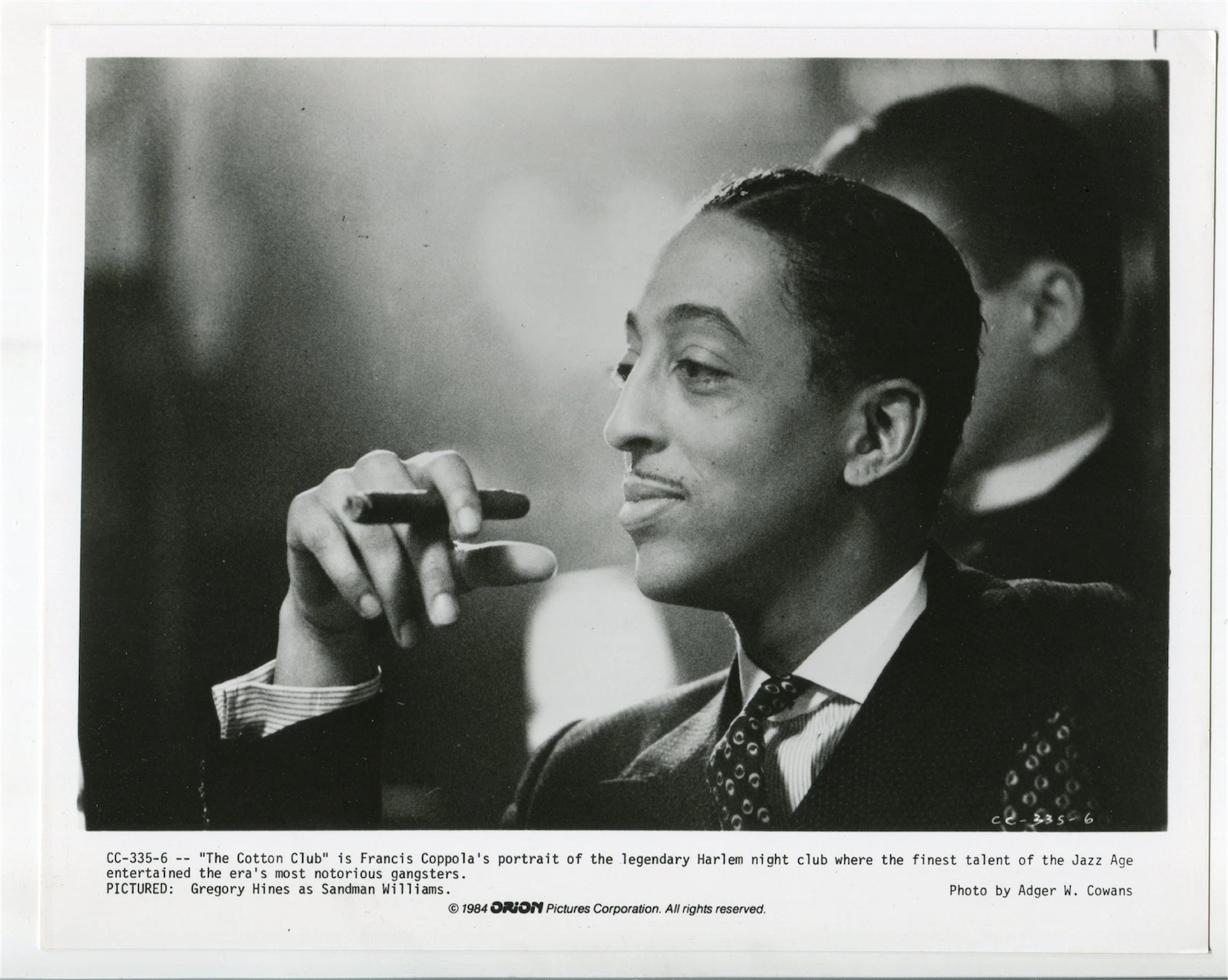

Tap’s American story is not separable from race, class, and the messy process by which Black art forms are celebrated, exploited, forgotten, and then rediscovered. By the time Hines reached adulthood, tap had already traveled a long route: from minstrel contamination and vaudeville circuits to Hollywood musicals, then into a period where it risked being framed as “old-fashioned,” a throwback rather than a living form.

Hines became a major figure in reversing that slide—partly because his talent was undeniable, but also because his sensibility was modern. He didn’t dance as though he were imitating classic Hollywood; he danced as though he were in conversation with jazz, with the street, with the present tense. His work insisted that tap was not a nostalgic accessory. It was an instrument—percussive, improvisational, capable of telling stories and carrying emotional weight.

The Smithsonian’s National Portrait Gallery, in describing him, uses the kind of language institutions reserve for artists who change the terms of the field: “Widely acknowledged as the greatest tap dancer of his day,” it notes, Hines “revitalized the genre” and “inspired a new generation,” including Savion Glover.

But that inspiration wasn’t vague. It was hands-on. It was practical. It involved giving tap a bigger stage—sometimes literally, sometimes politically.

Broadway: The proving ground

Hines’ Broadway career helped cement him as more than a brilliant dancer. Broadway is an arena where a performer must integrate: acting, singing, stamina, storytelling, and the ability to hold attention even when the choreography stops. Hines, by most accounts, wanted that challenge. He took roles that tested whether tap could exist not as a specialty act but as narrative engine.

He appeared in major stage works that leaned into jazz history and American musical heritage. In “Sophisticated Ladies,” the Ellington revue that arrived on Broadway in the early 1980s, he was part of a production that treated the Black musical tradition not as fringe but as central repertory. The Library of Congress, in a historical overview of tap, explicitly places Hines in this period—evidence of how his Broadway presence was not just personal success, but part of tap’s visibility cycle.

And then came “Jelly’s Last Jam,” George C. Wolfe’s musical about Jelly Roll Morton—composer, self-mythologizer, and one of the architects of jazz’s early public identity. Hines played Morton, a role requiring charisma and complexity: the seductions of talent, the costs of ego, the cultural collisions of American music. In 1992, Hines won the Tony Award for Best Actor in a Musical for the performance, an official marker of artistic achievement that also matters symbolically. A tap dancer—an artist from a form too often treated as novelty—was being recognized at the highest level of theatrical prestige.

He was also credited with tap choreography for the show, underlining how he functioned as both interpreter and maker.

The award did not make his legacy, but it clarified something crucial: Hines was not simply carrying tap. He was carrying whole productions. He was a leading man.

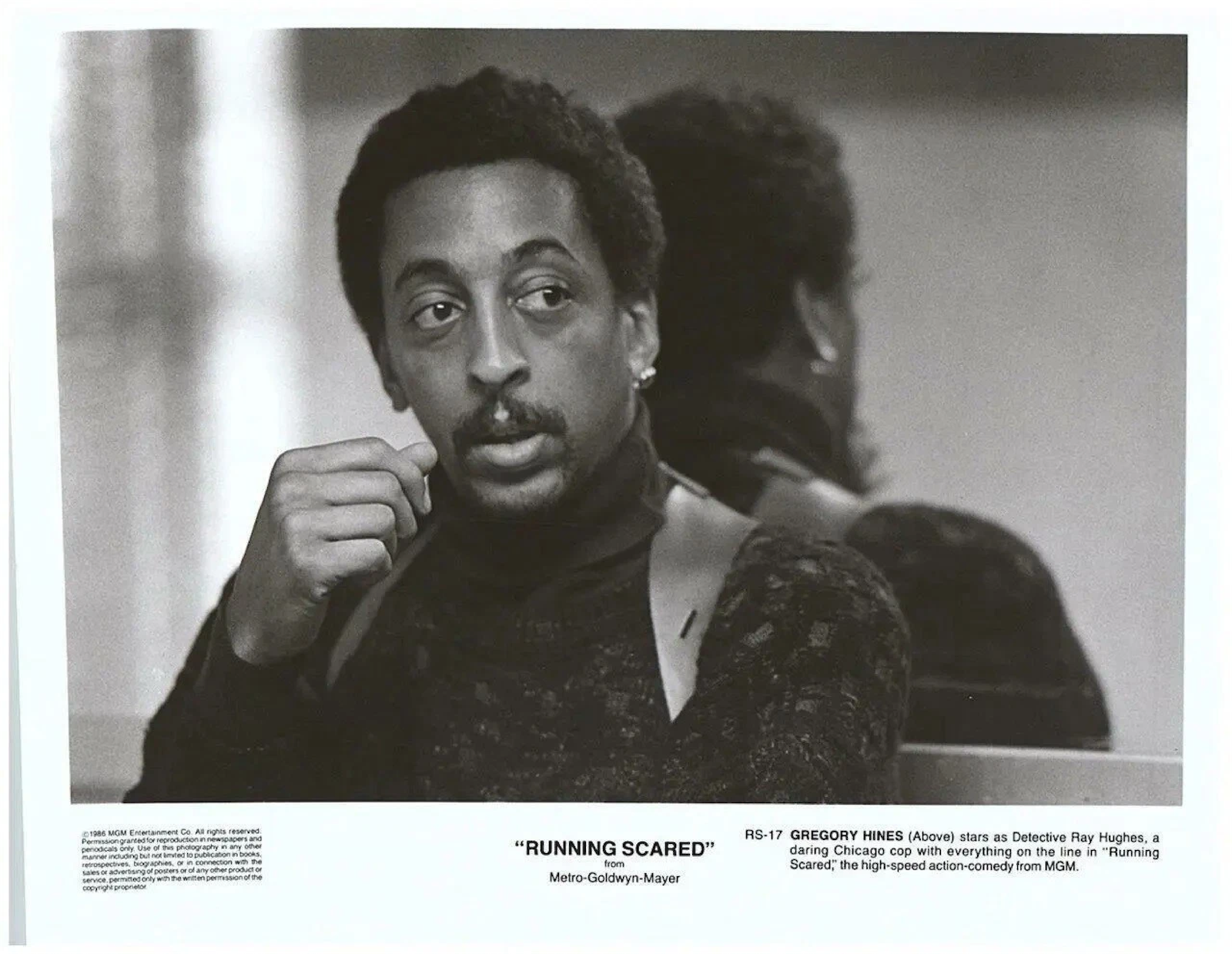

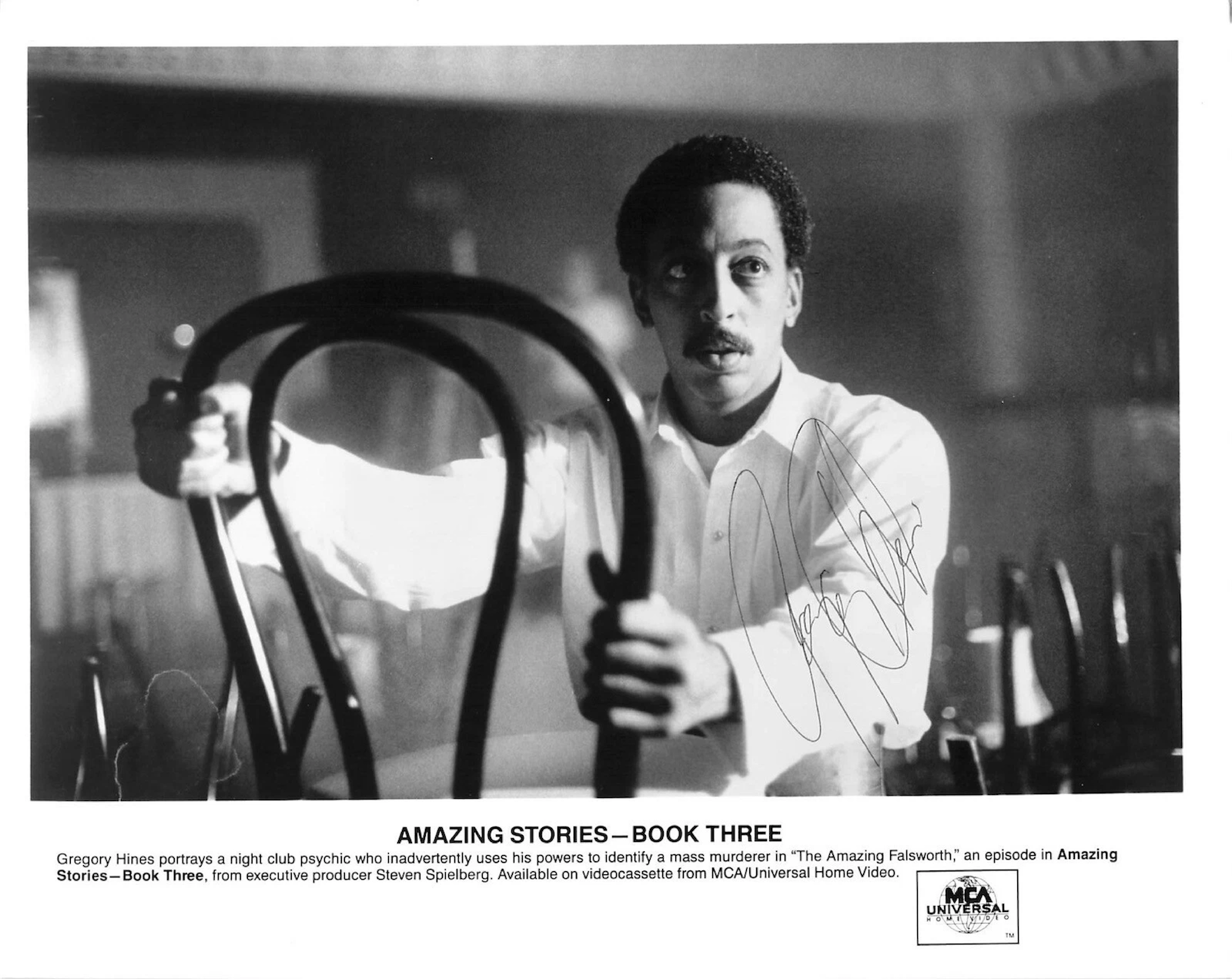

Hollywood and the choreography of masculinity

If Broadway gave Hines legitimacy in the formal arts ecosystem, Hollywood gave him reach. Film allowed millions who might never attend a tap show to see what tap could do when shot with care—and also to see what a dancer could be when he refused to play only the dancer.

His screen career was varied, spanning dramas, comedies, and television roles. But what stands out is how his dancing often carried narrative weight even when the script did not explicitly “require” it. His presence changed the temperature of a scene. Even standing still, he carried rhythm in his posture—a subtle sense that movement was always an option.

The Los Angeles Times obituary described him as “innovative and influential,” noting that he became “invaluable in the renewal of his art” while also enjoying “wide success as a film and television actor.” It singled out his “distinctively earthy, roughhewn tap style,” a phrase that captures how he moved against the stereotype of tap as genteel. Hines could be elegant, but he was never fragile. His tap was physical, grounded, and insistently Black in its musical intelligence.

That matters because American entertainment has often limited Black male performers to narrow archetypes. Hines expanded the frame. He could be charming and funny, but he also conveyed authority. He moved like a man who owned the room, and he did so without surrendering the complexity of the tradition behind him.

“Tap”: A film that functions like a meeting

One of the most consequential artifacts of Hines’ career is not a single performance but a kind of gathering: the 1989 film “Tap.” In popular memory, it’s often remembered as a movie “about tap.” In the tap community’s deeper accounting, it functions as a convening space: a place where older masters and younger artists appear on the same screen, where tradition is shown as living exchange.

The Guardian obituary captured this “bridge” role with unusual clarity, writing that Hines “spanned the gap between the swing era and the new generation, led by Savion Glover,” and that “nowhere was his role as a bridge more important than in Tap (1989),” where he appeared alongside both Glover and his “boyhood idol,” Sammy Davis Jr.

That sentence contains an entire philosophy of legacy. It frames tap not as a ladder but as a circle: elders, idols, protégés, all sharing the same floor. It also reveals something intimate about Hines: he remained, even at the height of his fame, a fan. He carried the memory of those who had formed him, and he wanted the world to see them.

Television: Documenting a tradition that could disappear

Hines’ stewardship took an even more explicit form in 1989, when he created and hosted “Gregory Hines: Tap Dance in America,” a PBS special that brought together veteran tap dancers, companies, and a new generation. The New York Public Library’s biography notes the program’s scope and its importance, emphasizing how it staged tap as a continuum rather than a single style.

The program’s recognition by the Television Academy underscores how it landed beyond the dance world. The Academy lists “Dance in America: Gregory Hines Tap Dance in Ameri” as receiving multiple nominations and an Emmy win (for editing) in 1989—technical recognition, yes, but also institutional acknowledgment that tap’s story was worth telling with seriousness and craft.

This was not merely content. It was cultural infrastructure: an artist using public television to build an archive of a form that had too often depended on oral history and fleeting live performance. Hines understood something many stars never have to consider: that if the elders died without documentation, whole vocabularies could vanish.

Mentorship and the next century of tap

Hines’ relationship with Savion Glover illustrates the difference between admiration and investment. He did not merely praise the young dancer; he framed him as essential to tap’s future. A CBS News piece from 2000, discussing Glover, quotes Hines in language that is both emphatic and strategic. He insists that people should not understate what they are seeing, calling Glover possibly “the best tap dancer that ever lived,” a “genius.”

It’s an extraordinary thing for a superstar to say, especially in a business that often rewards jealousy. Hines’ praise was “unstinting,” as the Guardian put it. And it was not naïve. By publicly elevating Glover, Hines was doing what tradition requires: transferring authority.

Tap, after all, is a form where greatness is not only achieved; it is recognized by the community. Elders anoint, sometimes reluctantly, often with a strict eye. Hines was willing to use his platform as a megaphone for that communal recognition.

A political instinct in an artist’s body

Some performers avoid politics, either out of caution or out of a desire to remain “universal.” Hines’ politics were rarely partisan in the conventional sense, but he carried a political instinct about culture: the belief that American art forms deserve public respect, and that recognition is not automatic—it must be fought for.

One of the clearest examples is National Tap Dance Day. In 1989, Congress passed a joint resolution designating May 25, 1989, as “National Tap Dance Day,” tied to the birthday of Bill “Bojangles” Robinson. The legislative text frames tap as a “multifaceted art form” and an expression of national cultural heritage, explicitly acknowledging the fusion of African and European elements in the making of an American form.

The resolution became Public Law 101-143, and the government’s archival record makes plain that this was not a symbolic rumor but enacted recognition.

Hines is often associated with the push for this recognition in popular accounts—an association consistent with his broader pattern: insisting that tap should not have to beg for legitimacy. Whether through television specials, film projects, or advocacy, he treated tap as something the nation should claim publicly, not quietly consume.

A career across genres—and an ease with risk

Hines’ acting career complicates any attempt to reduce him to “tap dancer who acted.” He took film roles across tones and genres, and he sometimes embraced projects that didn’t fit the safe prestige track. That willingness is part of what made him a true American entertainer rather than a single-lane artist.

He could appear in a glossy film world and still seem like himself. That is a difficult magic trick for dancers in cinema, where choreography can be edited into illusion. Hines’ authority came not from camera tricks but from an unmistakable relationship to rhythm. He looked like a musician because he was one—his instrument simply happened to involve wood floors and metal plates.

His versatility also mattered because it kept tap visible. In decades when tap risked being framed as retro, Hines showed up in mainstream contexts: television series, guest roles, children’s programming. His voice work on “Little Bill” brought his presence to a generation that might not yet know the names of tap’s elders.

In this sense, he functioned like a roaming ambassador for the art form, not through lectures but through proximity. People who tuned in for comedy or drama encountered, sometimes unexpectedly, a man whose body had been shaped by one of the most intricate dance languages America has produced.

Death, and the shock of absence

In August 2003, Hines died at 57. Obituaries described him as a star who had kept his illness largely private. The Los Angeles Times reported that he died of cancer in Los Angeles and emphasized what his death meant not only for film and theater audiences but for tap itself. The Guardian obituary, written with an insider’s attentiveness, framed his absence as a structural loss: the bridge had been removed, and the community would have to rebuild crossings through memory and mentorship.

The grief that followed was not merely for a celebrity. It was for a particular kind of artist: the one who makes a tradition feel contemporary without stripping it of history.

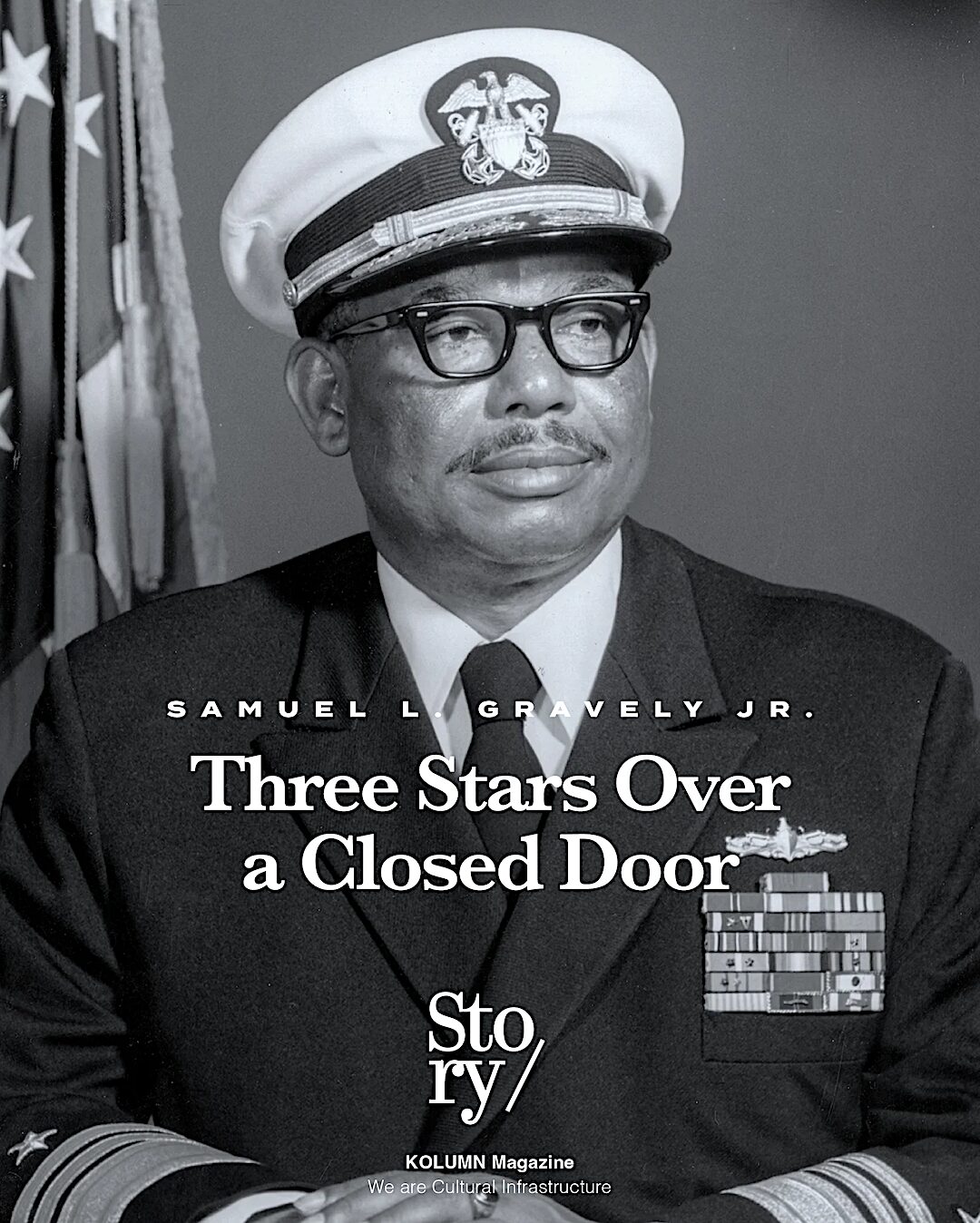

The afterlife of a public figure: stamp, institution, canon

American culture often waits until after death to decide what an artist “meant.” Hines’ posthumous honors reveal how widely his meaning was felt.

In 2019, the United States Postal Service issued a Gregory Hines Forever stamp as part of its long-running Black Heritage series—official commemoration that placed him in a national gallery of historical memory, alongside figures whose influence is treated as foundational.

A postage stamp is small, but it is also one of the most everyday forms of canon-making the U.S. government performs. It turns a life into a circulating icon. It suggests not only that the person mattered, but that the person belongs to the country’s story.

That same institutional arc appears in how libraries, museums, and historical overviews now speak of him. The New York Public Library highlights his role as host and creator of tap’s televised history. The Smithsonian frames him as a revitalizer who inspired those who came after. The Library of Congress includes him as a key figure in tap’s late-century timeline, placing him inside the long narrative rather than as a footnote.

This is what it looks like when an entertainer becomes more than a performer: when the work starts to read like a form of preservation.

Why Gregory Hines still matters

To say Gregory Hines was one of the great tap dancers is true but insufficient. Greatness in tap is not solely about speed, clarity, or the ability to hold a crowd. It is also about vocabulary: what you add to the language. It is about generosity: how you treat the elders whose shoulders you stand on. It is about continuity: whether the form grows when you arrive, and whether it can keep growing when you leave.

Hines mattered because he understood the stakes. Tap is an American art form that has repeatedly been asked to justify itself—asked to prove it is modern enough, serious enough, “relevant” enough. Hines answered those demands not by pleading but by performing. He showed tap as living music. He placed it in theaters and on screens. He documented it. He defended it in public. He praised the young with a sincerity that pushed them forward.

And he did all of it while remaining, unmistakably, a star—an artist whose charisma and humor and ease gave him access to audiences that might never have sought out tap on their own.

There is a moment described in the Guardian obituary that feels like a miniature of his whole life: at a crowded reception in London, he spots Will Gaines—one of the last jazz hoofers—and he literally climbs over packed tables to reach him, to shake his hand. It’s a story about respect so intense it becomes physical. It suggests an artist who understood that lineage is not theoretical. Lineage is somebody still alive in the room, somebody you must reach—no matter what’s in the way.

That, finally, is the shape of his legacy. Gregory Hines did not treat tap as a thing he owned. He treated it as a world he belonged to—and as a world he was obligated to keep open.

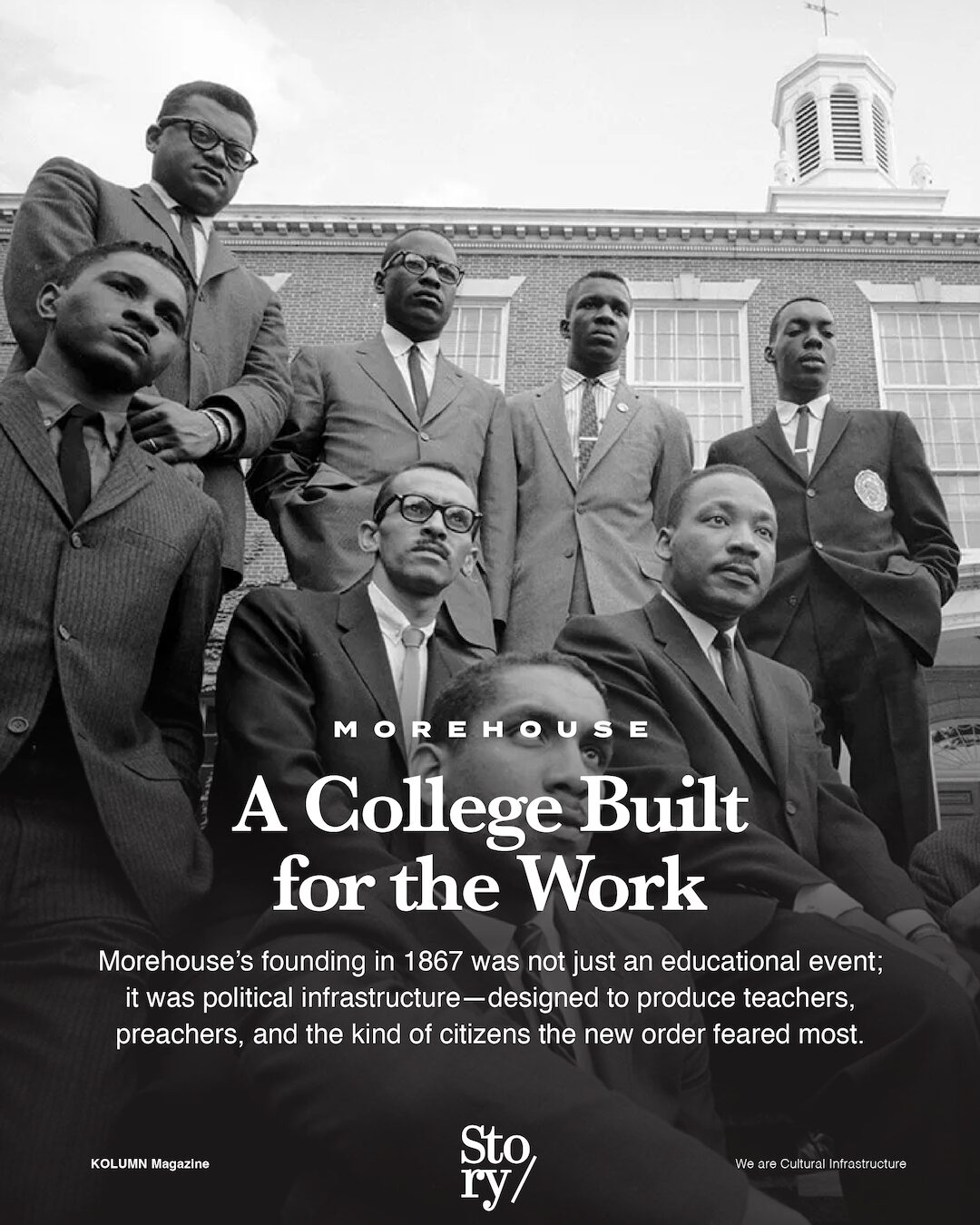

More great stories

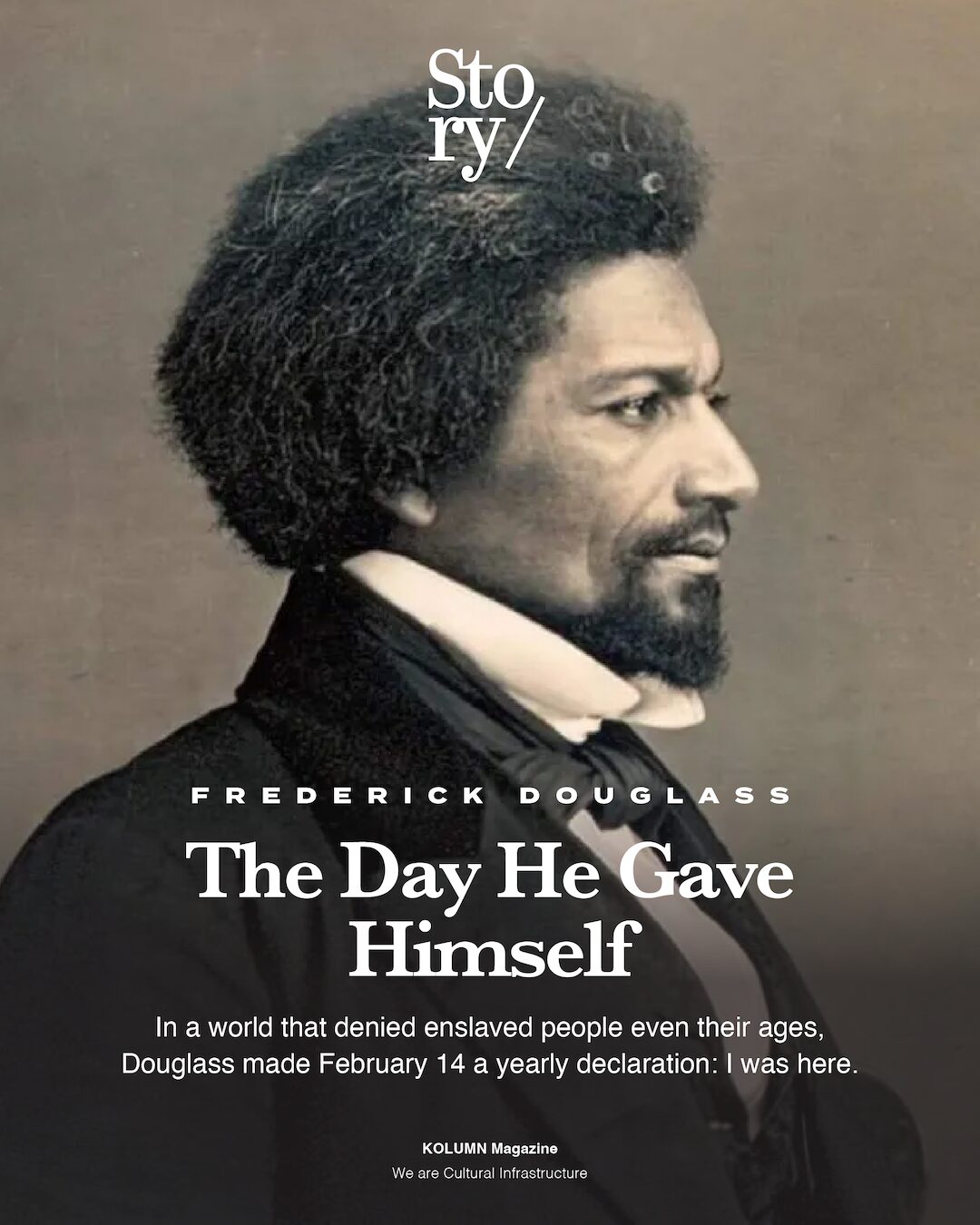

Frederick Douglass: The Day He Gave Himself