To ask why Douglass celebrated on February 14 is to ask a broader question: What do people do when the archive won’t give them their own beginnings?

To ask why Douglass celebrated on February 14 is to ask a broader question: What do people do when the archive won’t give them their own beginnings?

By KOLUMN Magazine

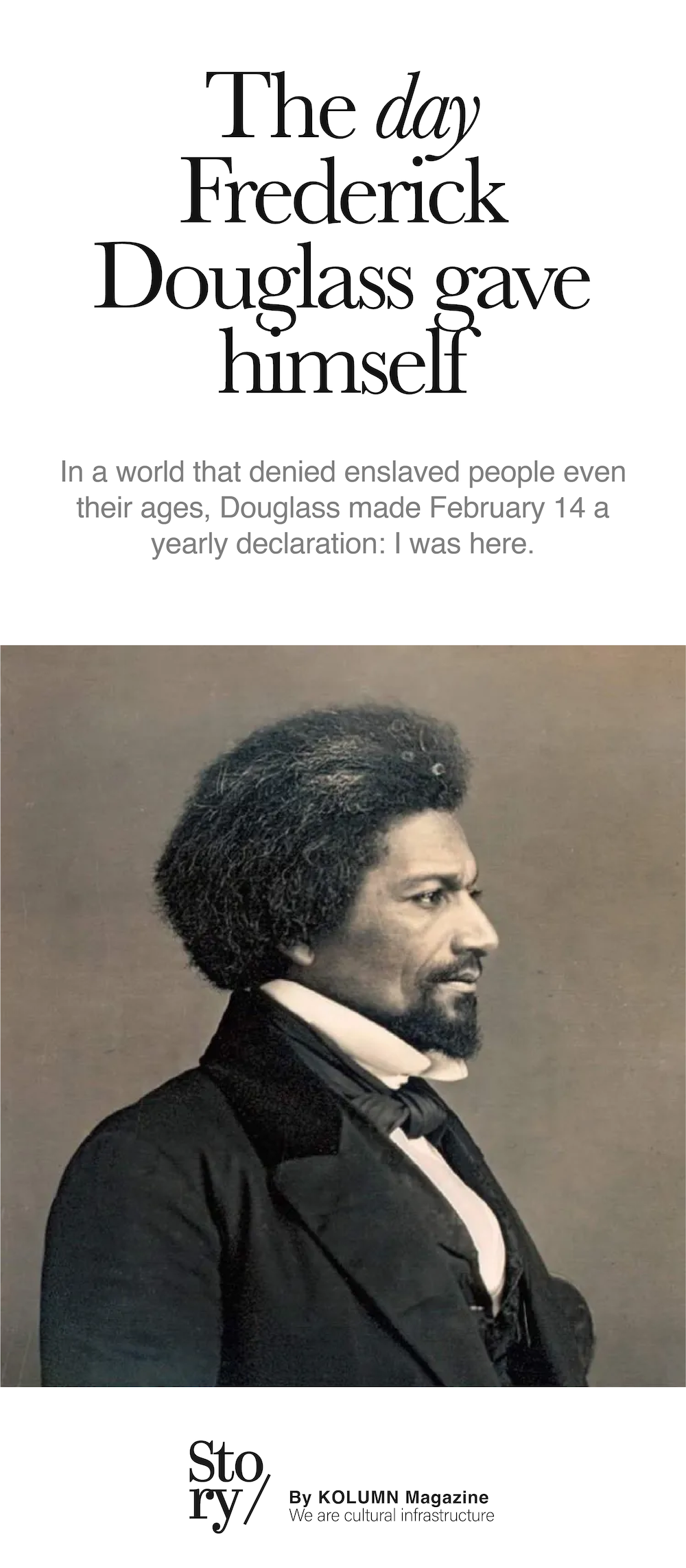

Frederick Douglass spent a lifetime converting deprivation into language—turning what was withheld from him into an argument against the system that withheld it. He did this with literacy, with wages, with voting rights, with the meaning of citizenship. But one of his most revealing conversions is also among the smallest facts people think they “know” about him: that Frederick Douglass was born on February 14.

He wasn’t. Or, rather, he almost certainly wasn’t—not in the tidy, calendrical way modern biography prefers. Douglass himself told readers early on that he had “no accurate knowledge” of his age and had never seen “any authentic record containing it.” He added the sharper point: enslavers preferred it that way, and enslaved people were kept as ignorant of birthdays as “horses” are of theirs.

This is where the story begins—not with Valentine’s Day, not with roses or cards, but with a system built to scramble a human being’s coordinates in time. Slavery did not merely seize labor. It severed genealogy, scattered families, and made the ordinary markers of personhood—names, anniversaries, even one’s own age—unstable, negotiable, and often unknowable. When Douglass later adopted February 14 as the day he would celebrate, he wasn’t supplying trivia. He was demonstrating how an enslaved child becomes an adult who has to invent what was denied.

The question “Why February 14?” has a simple public answer and a deeper private one. The public answer is that he chose it. The private one is why he chose it, and what that choice let him do.

A man who could not know the date

Douglass was born enslaved on Maryland’s Eastern Shore. In his first autobiography, Narrative of the Life of Frederick Douglass, an American Slave (1845), he wrote with a precision that is easy to mistake for certainty: he names a place—Tuckahoe, near Hillsborough, in Talbot County—and then immediately withdraws the one detail readers most expect. “I have no accurate knowledge of my age,” he states, because he had never seen a record of it.

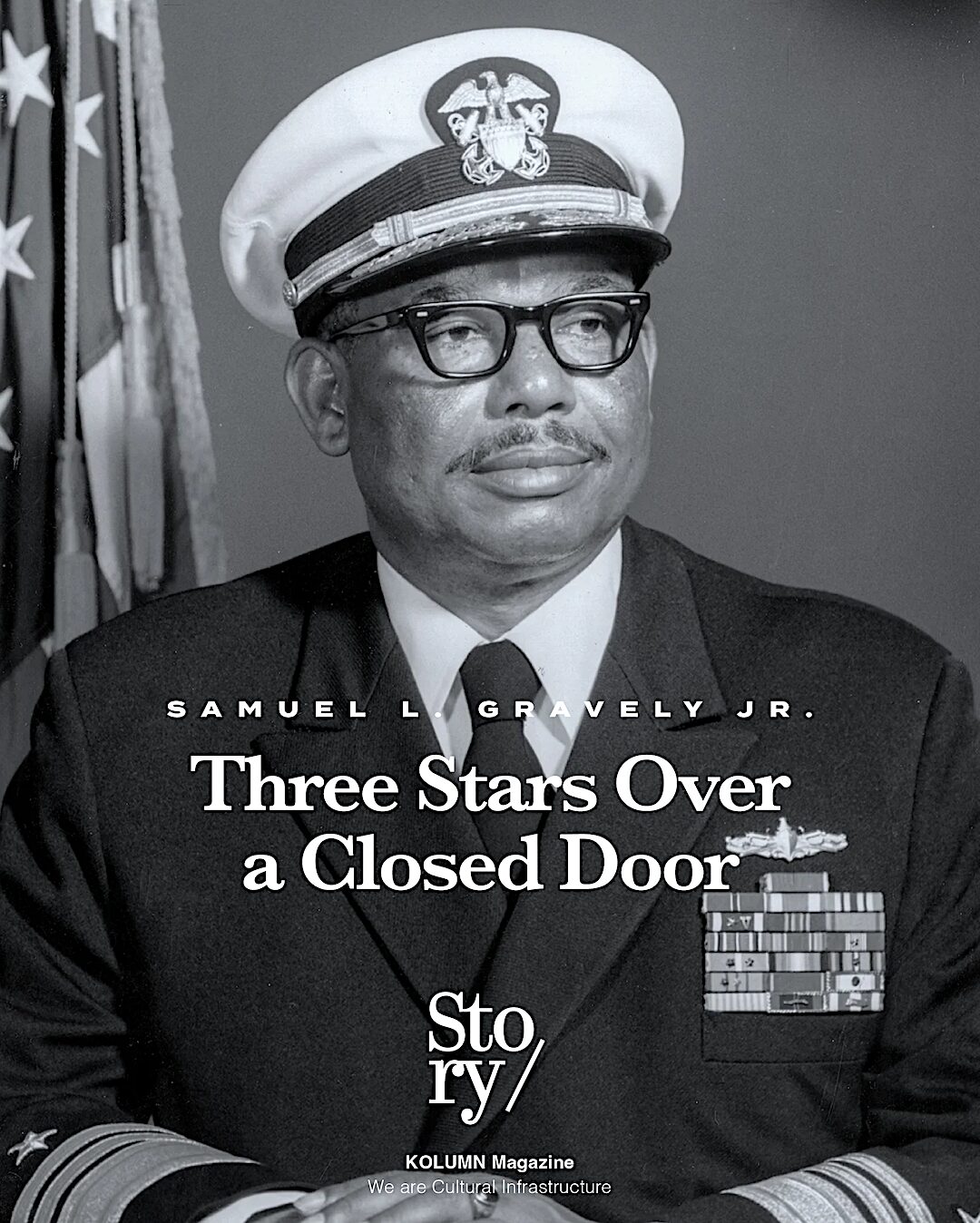

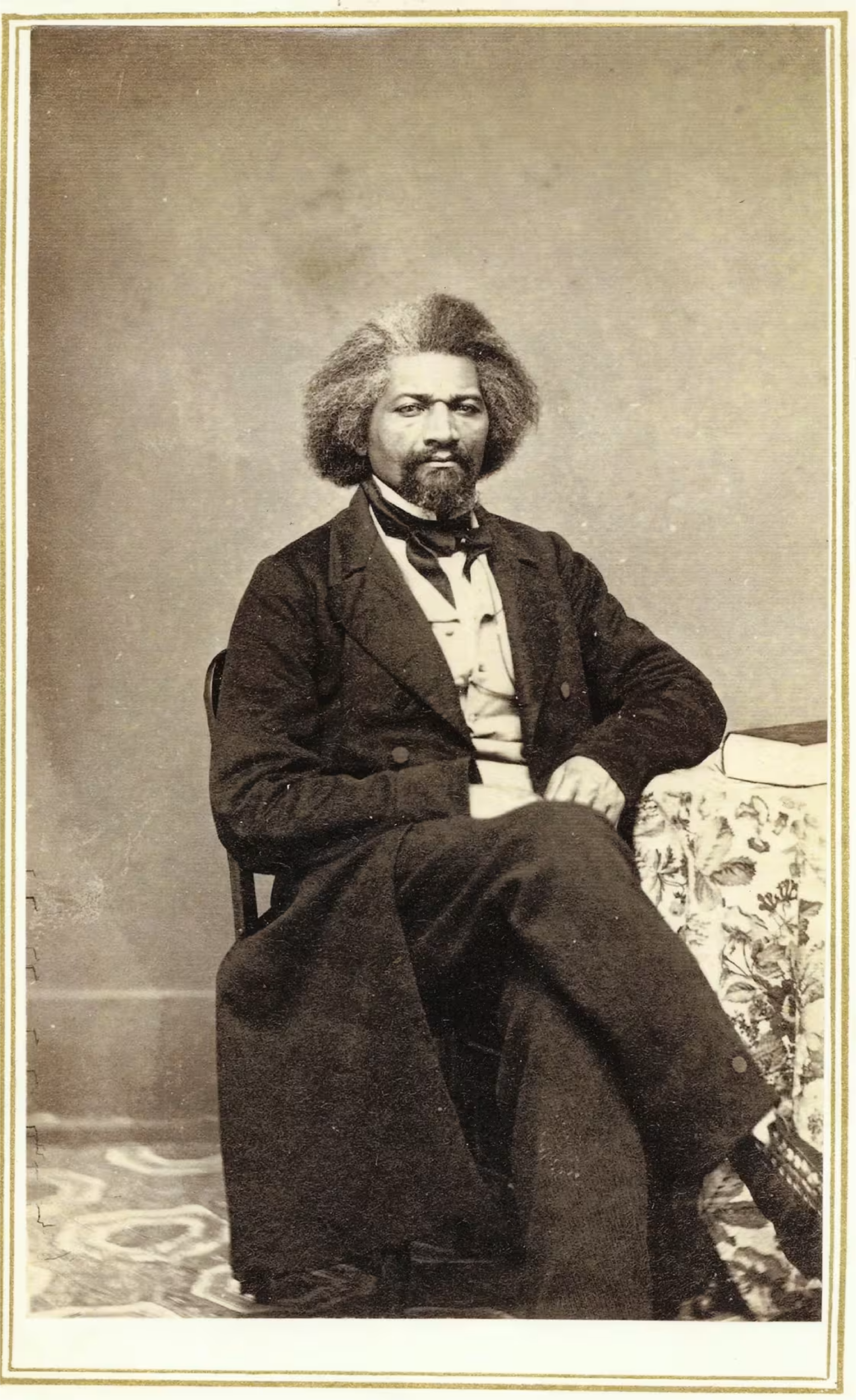

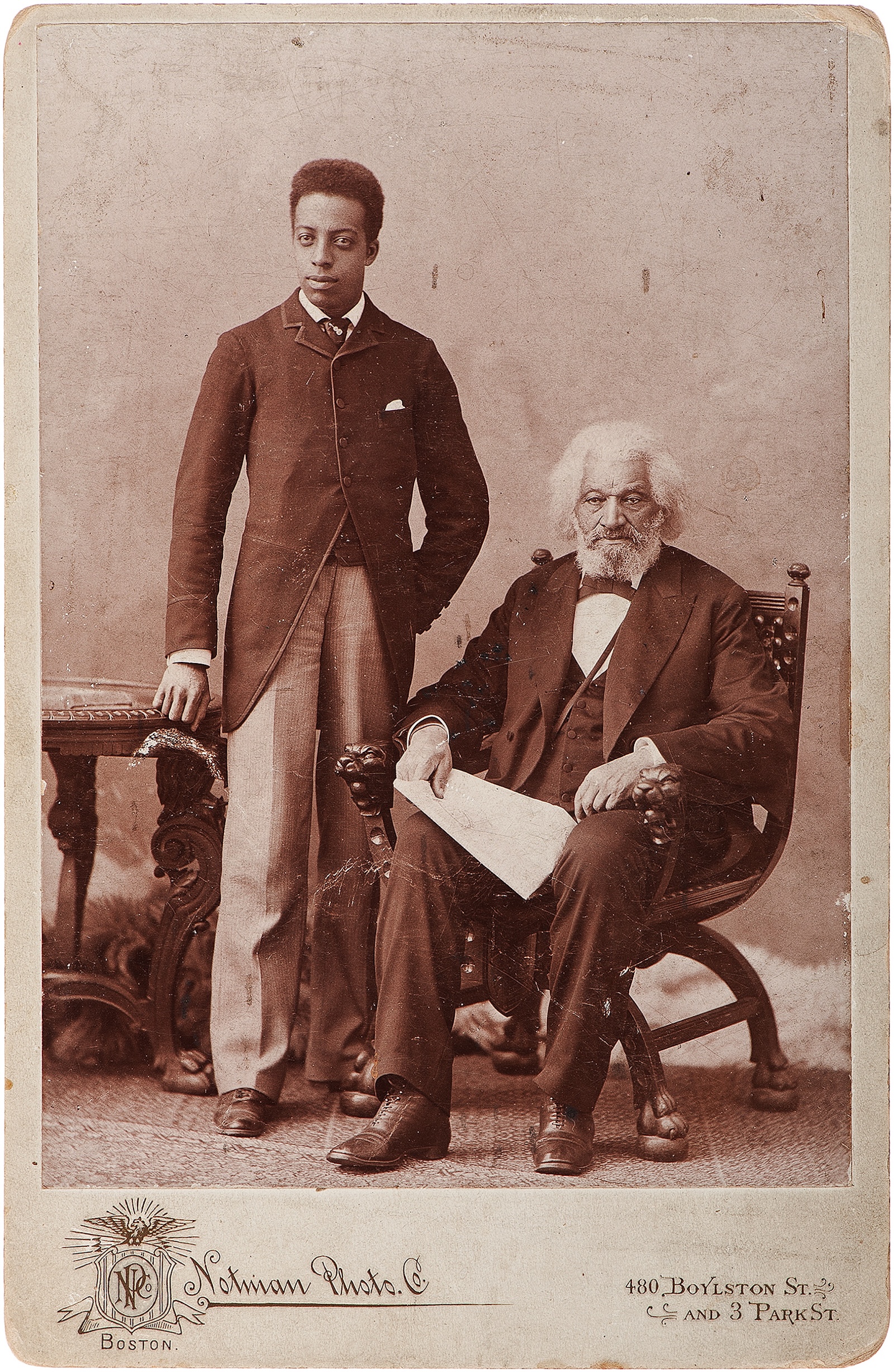

That passage is often quoted as a general indictment of slavery, which it is. But it is also a personal admission: Douglass entered public life missing a basic fact that almost everyone else in his readership could assume about themselves. That missing fact mattered socially. It mattered politically. It mattered psychologically. In a century that was obsessed with moral character and personal origin stories, Douglass—who became one of the most photographed Americans of the 19th century—was also a man whose own beginning was, in the official sense, undocumented.

Not undocumented in the way that suggests mystery for mystery’s sake, but undocumented because slavery had no reason to honor the kind of record-keeping that grants dignity. The slave ledger might note purchase price, labor capacity, punishments, and “increase.” A precise birthday—an intimate detail marking a child’s entrance into the world—was optional at best.

And yet Douglass lived long enough, and rose high enough, that the absence began to chafe. The need to know is one of the quiet subplots of his story: the longer he lived as a free man, the more he recognized what slavery had stolen not only from his body but from his biography.

The clue that wasn’t a date

Over time, historians narrowed the likely year of Douglass’s birth. Many modern biographies and reference works cite February 1818 as the month and year most consistent with surviving records, even as Douglass himself at different points estimated 1817. But the day—the part people now repeat with confidence—remained, in the strict historical sense, unverified.

Douglass’s decision to celebrate February 14 is therefore best understood as an act of authorship. He made a date where the archive did not.

Several modern accounts trace his choice to a memory of his mother, Harriet Bailey, calling him her “Little Valentine.” It is an almost startlingly soft detail in a life famous for iron rhetoric. But it’s the kind of detail that survives when so much else does not: a nickname, a tone, a fragment of affection carried forward from childhood. Contemporary explainers and commemorations—among them the National Constitution Center and other historical institutions—have emphasized that Douglass chose February 14 because of that maternal nickname.

There is also another maternal image that deepens the association with Valentine’s Day, and it comes from Douglass’s own writing as well. A recent Essence piece, drawing from My Bondage and My Freedom (1855), highlights his recollection of his mother giving him a “sweet cake” shaped like a heart during what would be one of their final meetings—an intimate symbol that reads, in hindsight, like a premonition of the holiday he would later adopt.

If you are looking for a single cause—this memory produced that date—life rarely obliges. But these fragments illuminate the logic of the choice. Douglass did not pick February 14 because it was popular. He picked it because it allowed him to anchor a life story to a rare, remembered tenderness—love surviving inside a system designed to extinguish it.

Valentine’s Day, remade

It is tempting to treat Douglass’s chosen birthday as a charming historical footnote: the great abolitionist, sharing a date with lovers. But that reading is too small for him.

Douglass’s life was, in part, a contest over meaning. He understood that words, symbols, and rituals were political instruments. His speeches read the country to itself; his newspapers tried to steer public conscience; his photography insisted on Black dignity against the caricatures of minstrel culture. A birthday celebration, in this context, becomes something else: a yearly rehearsal of personhood.

Valentine’s Day in America has often been sentimental, commercial, and private. Douglass’s February 14, by contrast, is public and insurgent. It is a day that asks a nation to remember that one of its most brilliant democratic theorists began life as property, and that even the date of his birth had to be reconstructed from memory and scattered paperwork.

The irony is not that his birthday falls on Valentine’s Day. The irony is that the holiday’s association with love makes it easier to overlook what Douglass was saying: that love, under slavery, was not only intimate but endangered—and that the loss of ordinary facts (like a birthday) is a form of violence.

“I have no accurate knowledge of my age”: The violence of unknowing

Douglass’s “no accurate knowledge” sentence is one of the most quietly devastating lines in American autobiography. It is also one of the most clarifying explanations for why February 14 matters beyond trivia. In the same passage, he links ignorance of birthdays to the slaveholder’s interest: “it is the wish of most masters…to keep their slaves thus ignorant.”

The ignorance is not incidental; it is engineered. To know your age is to be located in time. To be located in time is to have a claim on your own life narrative. Slavery preferred workers unmoored from their own timelines—people for whom the past is obscured, the future is controlled, and the present is labor.

When Douglass later emerged as a self-made public figure, he did so as an architect of his own story. His autobiographies were not only testimony; they were counter-archives. Each book revised and expanded the last, adding nuance, correcting earlier omissions, and clarifying his development. That arc alone—three autobiographies, each rethinking what a life story can do—explains why a chosen birthday would matter to him. The man who wrote himself into freedom also wrote himself into time.

The ledger, the former enslaver, and the hunger for fact

In later life, Douglass tried to recover what could be recovered. Several modern recountings describe him learning the month and year of his birth by consulting or learning of records connected to his enslaver, but finding that the exact day was missing.

That detail—month and year present, day absent—fits the logic of slavery’s paperwork. A plantation ledger may record what is useful for property management. A precise birthday, unless it serves some transactional purpose, can remain blank.

The blank became Douglass’s opening. February, he concluded, was likely. The 14th—his mother’s “Little Valentine”—became the day he would claim.

What’s striking is that his chosen date is not random even as it is unverifiable. It is an interpretation of evidence: a month remembered, a year inferred or recorded, a day selected for meaning. Douglass, as ever, turns uncertainty into a deliberate statement.

The afterlife of a chosen birthday: Douglass Day

If the story ended with Douglass privately celebrating February 14, it would still be telling. But it didn’t remain private. Over time, communities began to formalize his birthday as a civic ritual, and in some places it became something close to a holiday.

The Smithsonian Transcription Center has traced the origins of “Douglass Day” to community activism in Washington, D.C., including efforts that led to a school holiday for Black children in the District—an institutional recognition of Douglass as a figure worthy of annual commemoration. In that telling, February 14 becomes more than Douglass’s personal solution to a missing record. It becomes a communal calendar entry: a day in which Black Washington, in particular, insisted on honoring a hero in a public system that frequently refused Black history.

That transformation matters. It suggests that people understood the stakes of Douglass’s choice. Celebrating him on February 14 was not merely repeating his preference. It was a way of building Black civic identity—teaching children, especially, that their heroes belonged in the official rhythms of the city.

In the 21st century, Douglass Day has taken on a new form that would have pleased the man who made newspapers his weapon: it has become a living archival project. The modern Douglass Day movement is widely associated with a transcribe-a-thon—collective public work to make Black history more searchable, more accessible, more legible in the digital age. Organizers emphasize that Douglass chose February 14 even though he never knew his exact birthdate, and they treat that day as an annual opportunity for “collective action” in service of Black history.

The Library of Congress has explicitly linked February 14 observances to transcription efforts through its “By the People” program and related educational resources, inviting the public to participate in projects tied to Douglass’s legacy.

In other words, a man who once lamented the absence of an “authentic record” has become the occasion for building records—thousands of volunteers producing searchable text from scanned documents so that Black history does not remain trapped in inaccessible images or scattered archives.

That is not merely poetic. It is political.

Why a birthday matters in a country that argued over his humanity

Douglass’s life spanned an America that fought a civil war over slavery, then spent generations arguing over what emancipation meant. He was not only a witness but a participant—an abolitionist, a newspaper editor, a diplomat, and a relentless critic of hypocrisy.

A birthday, in such a life, becomes a staging ground. It is a day that invites the question: What does it mean that a person like Douglass had to choose? It makes the violence of slavery legible in a new key. It also makes Douglass’s agency legible: he refused to let the absence of documentation define his life.

The modern observance of February 14 as Douglass’s birthday—appearing in public events calendars and museum programming—often treats the date as a settled marker even while acknowledging the underlying uncertainty. That tension is part of the story: institutions want a date for scheduling; historians want accuracy; communities want a ritual; Douglass wanted dignity.

The February 14 tradition is therefore an uneasy truce between the archive and the need for commemoration. It is a reminder that for enslaved people, the archive itself was often an instrument of domination—partial, property-centered, and indifferent to interior life.

The tenderness at the center: Harriet Bailey’s shadow

Any honest account of Douglass’s February 14 must also confront the fact that the “Little Valentine” memory exists inside a larger story of forced separation.

Douglass’s relationship with his mother was defined by distance. Enslaved mothers and children were often separated by plantation logistics; visits could be rare and controlled. Douglass wrote elsewhere about the limited contact he had with Harriet Bailey and how early she died relative to his childhood. Accounts that focus on the “Little Valentine” nickname frequently emphasize how few memories of her he retained.

That scarcity is itself the point. If one of the only surviving maternal details is a nickname, then using it as a basis for a birthday becomes a form of repair. Douglass is not merely picking a romantic holiday. He is preserving his mother’s voice in public time—ensuring that once a year, at least, the world repeats an echo of what slavery tried to erase.

The heart-shaped cake memory, as recounted in interpretations of My Bondage and My Freedom, amplifies this: love expressed in the simplest form (food, shape, sweetness) becomes a relic, and that relic becomes a date.

In Douglass’s hands, sentimentality is not escapism. It is evidence.

The expert lens: Biography, scholarship, and the “invented” date

The best modern scholarship does not ridicule Douglass’s chosen birthday; it contextualizes it. Douglass’s life has been reconstructed through exhaustive research—manuscripts, newspapers, correspondence, government records, and the writings he left behind. In public discussions of his biography, scholars such as David W. Blight have emphasized both the uncertainty of the exact date and the meaning behind Douglass choosing February 14.

You can see the interpretive consensus across formats: explanatory essays, institutional histories, public humanities projects. The details repeat because they are well-attested in secondary accounts and consistent with Douglass’s own testimony about lacking an authentic record. The date’s power lies not in documentation but in what it reveals about how enslaved people navigated identity when documentation was either absent or hostile.

February 14, in this light, is not a mistake that needs correcting. It is a clue: a small ritual that points toward the larger architecture of slavery and the larger genius of Douglass—his capacity to convert personal loss into public meaning.

A national habit of simplifying him

There is another reason this story deserves a longform treatment: Americans have a habit of simplifying Frederick Douglass.

He is often flattened into a few famous photographs, a few famous quotes, a few famous speeches. He is invoked as proof of progress or as a scolding conscience, depending on the era. Even the celebration of his birthday can become a soft-focus moment—“Happy Birthday, Frederick Douglass!”—without forcing the harder question: Why did he have to choose a birthday at all?

That question is uncomfortable because it exposes the mundane cruelties that accompanied the spectacular ones. Whippings are dramatic; stolen birthdays are quiet. But the quiet thefts accumulate into a comprehensive assault on personhood.

February 14 insists that we keep the quiet theft in view.

The modern public square: Honors, plaques, and politics

The afterlife of Douglass’s legacy is not merely cultural; it is also political, and it is still unfolding. In February 2026, for example, the U.S. House of Representatives renamed a press gallery after Douglass, recognizing his historical role as the first Black member of the congressional press corps—an event reported as part of ongoing debates about American history and public memory.

That kind of honor shows how Douglass continues to function as a symbol in contemporary struggles over who gets named, who gets remembered, and how institutions narrate the past. The fact that such ceremonies often occur near February 14 is part of the modern rhythm: Douglass’s chosen birthday has become a convenient anchor point for civic recognition.

But it also means that the date risks being absorbed into institutional pageantry, losing the sharpness that made it meaningful in the first place. If February 14 becomes merely a convenient annual platform, then the story it contains—slavery’s erasure and Douglass’s reclamation—can fade into background music.

Douglass Day’s transcription culture pushes against that. It insists on labor, not just applause: sit down, open the document, read the handwriting, type it out so that someone else can search it later. The method is fitting. Douglass built his life on literacy as action.

The journalism lesson inside the birthday

For a journalist, February 14 is also a parable about evidence and power.

In ordinary reporting, a birth date is a routine fact, verified by certificate. In Douglass’s case, the absence of a birth certificate is itself the fact. It is a story about the conditions under which records are kept and what those conditions say about human value.

Douglass teaches that the archive is not neutral. Records reflect the priorities of the record-keeper. Under slavery, the record-keeper’s priorities were profit, control, and property. The interior life of an enslaved child did not merit meticulous documentation. Douglass’s chosen birthday therefore becomes a critique of the archive, and his later fame becomes an argument that the archive must be read against itself.

This is also why the modern transcription movement matters. It is an attempt—imperfect, ongoing, collective—to build a public archive that is searchable and shared, not locked in institutions or in the private hands of those who can afford access.

If slavery’s paperwork dehumanized, Douglass Day’s paperwork rehumanizes.

A date that holds contradiction

February 14 holds contradictions that are worth stating plainly.

It is a chosen birthday that is often treated as a factual birthday. It is a sentimental holiday repurposed into a political memorial. It is a celebration rooted in love that exists because of violence. It is a stable annual ritual born from instability.

And it is also a reminder of something else: Douglass did not need a verified birth date to become Frederick Douglass. But he wanted one anyway—or at least wanted the dignity of claiming a day. That wanting is human. It is also historically consequential, because it became contagious: communities adopted the date, taught it to children, wrote it into programs, revived it in digital humanities.

The date matters not because it is certain, but because it is insisted upon.

What we do when the archive won’t give us a day

To ask why Douglass celebrated on February 14 is to ask a broader question: What do people do when the archive won’t give them their own beginnings?

Douglass’s answer was to choose, and then to build rituals around the choice. He anchored the choice in the faint but luminous memory of his mother’s voice—“Little Valentine”—and in the emotional logic of a heart-shaped cake, a small maternal offering that slavery could not convert into property.

He then lived a life so large that the chosen day outgrew him. It became Douglass Day in Black Washington; it became a day for civic events and wreath-layings; it became, in the present, a day for mass participation in the work of transcription and historical recovery.

This is the story behind the date: not a quirky coincidence with Valentine’s Day, but a narrative of stolen information and reclaimed identity.

In a nation that once denied Douglass the status of a full human being, it is fitting that one of the most repeated facts about him is, in a strict sense, a fact he had to author himself.

February 14 is not simply when we remember him.

It is how we remember what was done to him—and what he did with it.

More great stories

Gregory Hines: Rhythm as Inheritance