Liberation is not an event but a process

Liberation is not an event but a process

By KOLUMN Magazine

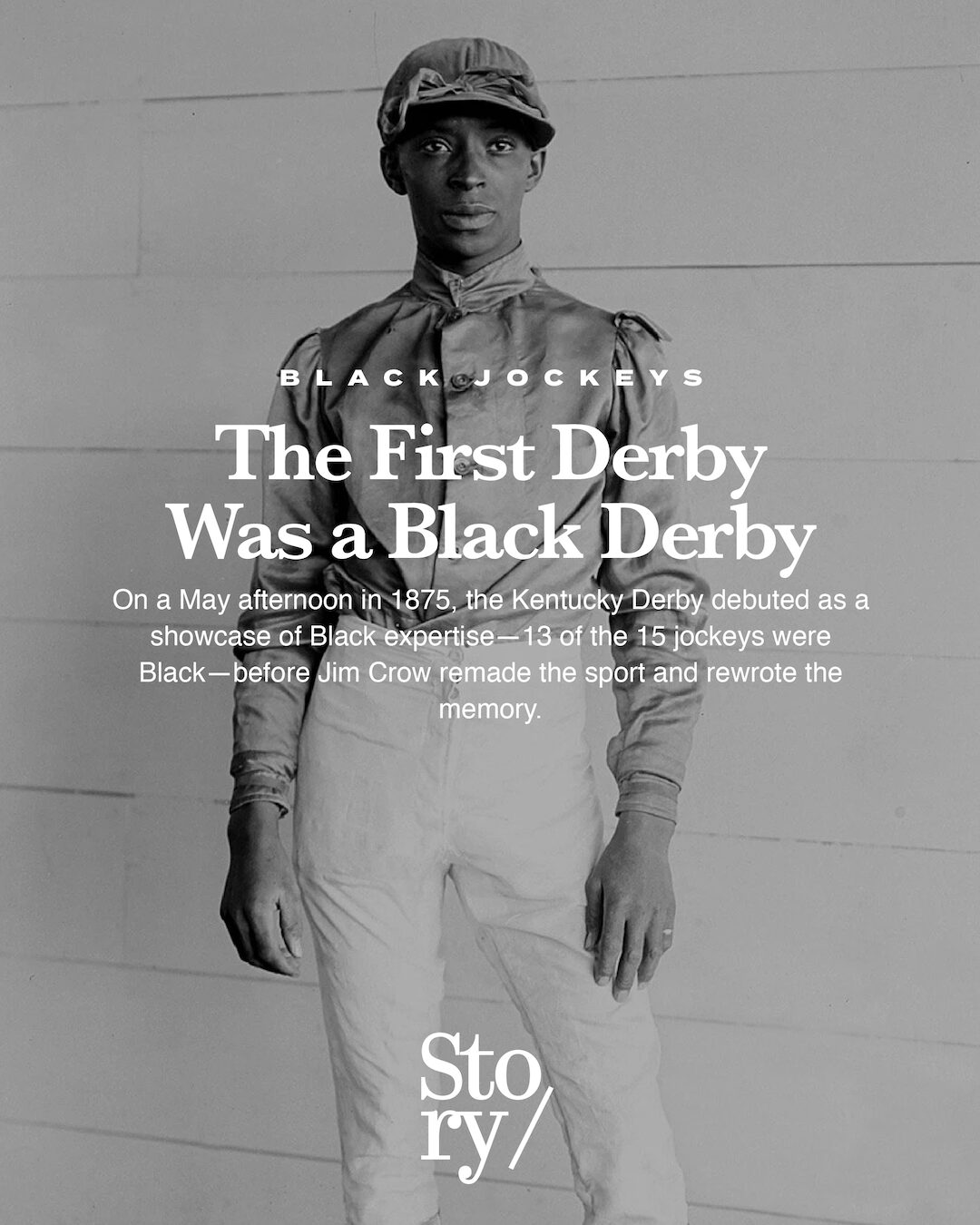

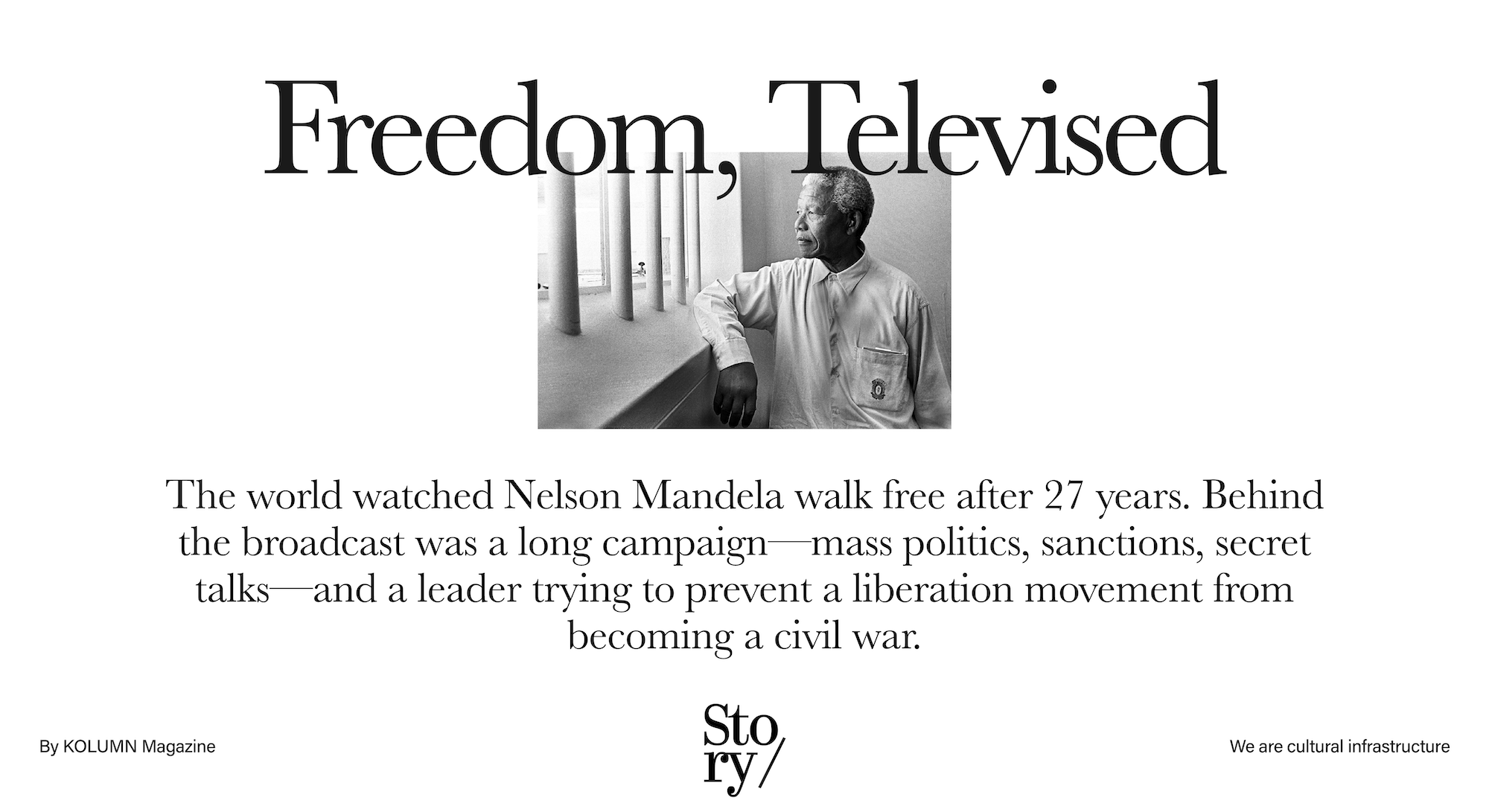

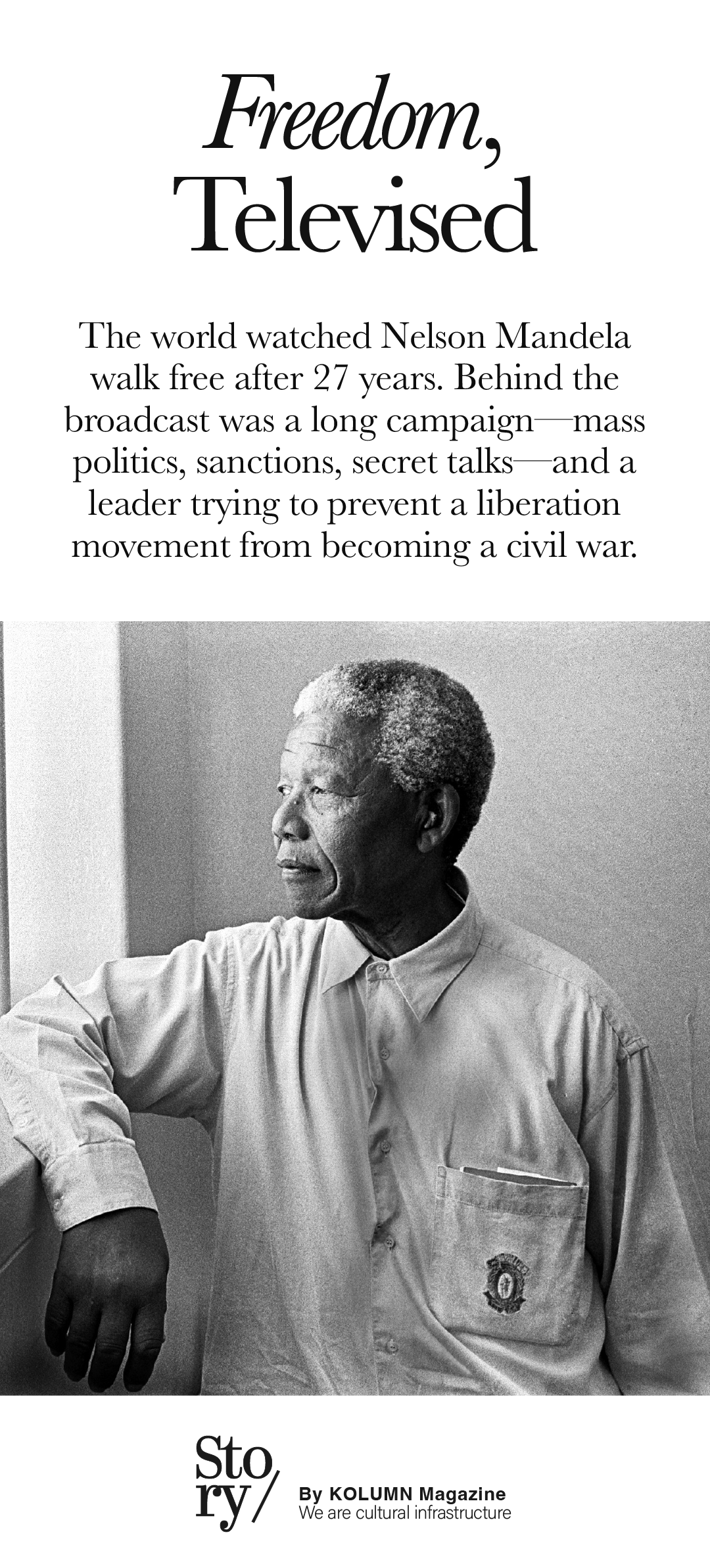

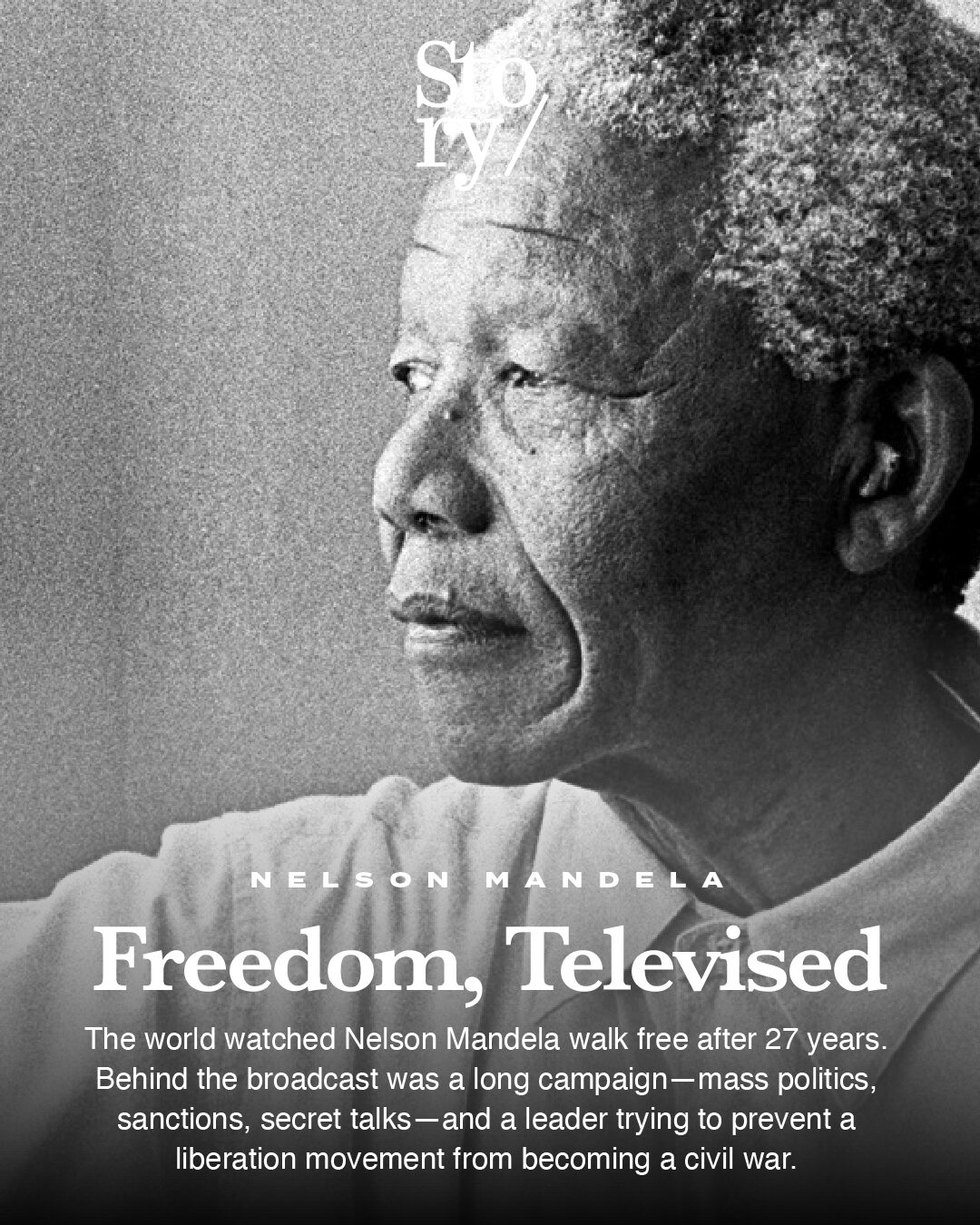

At a prison gate near Cape Town, history arranged itself into a photograph.

On February 11, 1990, Nelson Rolihlahla Mandela—prisoner, insurgent, lawyer, symbol—walked out of Victor Verster Prison after 27 years in captivity, his hand clasped in Winnie Madikizela-Mandela’s, his other arm rising into a gesture that could be read as salute, triumph, warning, prayer. The moment played live to millions; it became, almost instantly, a shared reference point—a timestamp people would use later the way they used other epochal scenes: the fall of walls, the lowering of flags, the first steps on a new surface.

But liberation movements are rarely completed at the moment of release. In Mandela’s case, the gate was not the end of a story; it was the beginning of a more precarious chapter: the conversion of moral authority into political settlement, under conditions designed to break countries apart. By February 1990, South Africa’s apartheid government was battered—economically constrained by sanctions, politically isolated, and increasingly unable to control townships that had become laboratories of protest and, at times, violent reprisal. The anti-apartheid movement, in turn, was powerful but fragmented, operating through internal mass structures and an exiled leadership, with an armed wing that had never been able to defeat the state militarily and a domestic base that was paying the daily price of repression. Internationally, the Cold War scaffolding that had long shaped Western governments’ tolerance for apartheid was shifting, and Pretoria’s claim that majority rule meant communist takeover was losing its force.

Mandela’s release was therefore both a concession and a calculation—made by President F.W. de Klerk’s government, demanded by a movement that had turned a single prisoner into a global referendum on racism, and staged in a way that acknowledged what everyone understood: that South Africa had become too big to ignore and too unstable to postpone.

The essential truth is that Mandela walked into freedom carrying multiple constituencies on his shoulders. He carried the African National Congress (ANC), freshly unbanned and emerging from decades of illegality. He carried the families of political prisoners and the dead. He carried the expectations of a generation of young activists who had matured in the 1980s under states of emergency, tear gas, and funerals. He carried, too, the anxieties of a white minority raised to believe that surrender meant annihilation, and the fears of Black South Africans who knew the state’s violence intimately and suspected that any “reform” could be an elaborate trap.

From his first hours outside prison, Mandela’s task was not merely to celebrate freedom but to discipline it: to keep a country from sliding into civil war, to keep a movement from mistaking symbolism for strategy, and to persuade an international audience that its role was not finished. If the campaign to free Mandela had been one of the late 20th century’s most successful moral projects, the campaign after his release would be something harder and less cinematic: the slow, contested work of building enough pressure—and enough confidence—so that enemies could agree to stop being enemies without pretending that the past had been harmless.

That is why Feb. 11, 1990 remains significant beyond the image. It announced the failure of apartheid’s claim to permanence, and it elevated a particular kind of political leadership: the ability to speak in the language of reconciliation while insisting, without apology, that justice was not optional.

What follows is the story of the lead-up to that day, the choreography of the release itself, and the international reception that greeted Mandela as he traveled soon afterward—an extraordinary circuit of capitals, parliaments, stadiums, and mass rallies where he was treated not as a private citizen newly freed, but as a head of state in waiting.

Before the gate: How a prisoner became a foreign policy problem

Mandela’s long imprisonment was not an accident of bureaucracy; it was an intended outcome of apartheid’s security logic. Convicted in the 1960s and sentenced to life, he spent years on Robben Island and later in other facilities—isolated, monitored, denied ordinary political life. The state sought to remove him from the public realm so thoroughly that his relevance would decay.

Instead, he became an emblem.

“Free Nelson Mandela” did not emerge simply because Western publics discovered South Africa’s cruelty; it emerged because South Africans and their allies built a sustained campaign that fused domestic resistance with international action. By the late 1970s and through the 1980s, Mandela’s name operated like a moral lever: activists used it to connect apartheid’s internal repression with the world’s external complicity—trade, investment, diplomatic engagement, sporting ties. Governments that would not openly endorse an insurgent movement found it harder to defend the imprisonment of a political leader whose primary crime, to many observers, was insisting that Black South Africans were human beings entitled to citizenship.

The escalation of internal resistance in the 1980s—the rise of mass democratic movements, strikes, township organizing, and the state’s increasingly militarized response—made apartheid look less like a stable system and more like an impending catastrophe. International sanctions and divestment campaigns began to bite. South Africa’s economy faced pressure; its cultural and sporting isolation became a source of shame; and its diplomatic position grew more tenuous as global opinion hardened.

At the same time, a quieter process was unfolding: secret and semi-secret contacts between apartheid officials and imprisoned or exiled ANC figures. These contacts did not imply mutual trust; they reflected mutual recognition that the old arrangements could not hold indefinitely. Mandela himself, while still incarcerated, became involved in discussions that hinted at the shape of what would later become formal negotiations. In other words, by the time the prison gate opened, the release was not an impulsive act of mercy but part of a broader political shift—one catalyzed by pressure from below and abroad, and by the state’s strategic need to manage its own decline.

The watershed came earlier in February 1990. In a major parliamentary address, President de Klerk moved decisively: political organizations including the ANC would be unbanned, and the state signaled that Mandela’s freedom was imminent. Whatever de Klerk’s motives—reformist conviction, pragmatic calculation, or a blend—the announcement acknowledged that apartheid could no longer be defended as merely “internal policy.” It had become a crisis of legitimacy with global stakes.

This lead-up matters because it clarifies what Mandela’s release represented: not a unilateral victory of one side, but the beginning of a negotiated transition under immense tension. The apartheid state still had police, prisons, and weapons. The liberation movement had legitimacy, mass energy, and international allies, but it also faced internal debates about armed struggle, the pace of compromise, and the danger of co-optation. Mandela’s release was a hinge between two kinds of conflict: the overt struggle against apartheid and the subtler struggle over what would replace it.

The release: A day of euphoria, disorder, and controlled message

Accounts of February 11, 1990 often emphasize the euphoria. They should also emphasize the chaos.

The world remembers the clean image of Mandela walking free. Less remembered is how volatile the day was: the uncertainty about timing, the massive crowds, the desperate logistics of security, and the fact that an entire political order was trembling. Contemporary reconstructions note the precise sense of arrival—down to the time stamp often cited in coverage—and the sheer scale of attention the moment commanded.

Mandela left prison and moved toward Cape Town, where he addressed a huge rally from the balcony of City Hall. What he said that afternoon is crucial, because it demonstrated that he understood the danger of the moment: a leader elevated into myth must also be able to behave like a strategist.

He began with greeting and gratitude, but he did not speak like a man newly rescued. He spoke like a commander returning to the field.

He reaffirmed commitment to peace, democracy, and freedom; he also reaffirmed the ANC’s disciplined objectives and insisted that the struggle’s purpose was not vengeance but a political transformation in which all South Africans—including whites—had a place. At the same time, he was clear that apartheid’s structures remained and that pressure must continue. In his address, he repeated a key line from his 1964 Rivonia speech—his willingness to fight against domination in any form—and placed it into the present tense, as if to tell both supporters and adversaries: nothing about prison had diluted the argument.

There is a particular kind of restraint in that speech that is easy to miss if you only remember the crowd’s roar. Mandela did not announce a utopia. He announced a program: negotiations, continued mass action, the necessity of unity, and an insistence that freedom would be measured not by a man’s release but by the dismantling of a system.

The speech also signaled something else: Mandela’s instinct for speaking simultaneously to multiple audiences. To Black South Africans who wanted immediate victory, he offered reassurance that compromise would not mean surrender. To whites who feared retribution, he offered an invitation—join us in building a new country. To international observers tempted to declare the problem solved, he offered a warning—do not confuse a symbolic moment with structural change.

Even the staging of the speech—the balcony, the mass of people, the city’s architecture—made a point: apartheid had sought to bury the ANC’s leader in a cell; now he stood above the public square, claiming visibility not as spectacle but as authority.

The first weeks: From symbol to negotiator, from prison discipline to movement discipline

Freedom creates expectations. It also creates vulnerabilities.

Mandela’s early weeks were consumed by the urgent work of movement management: reestablishing formal political structures, coordinating with exiled leadership, setting priorities, and responding to a country in which political violence had not paused just because one man had been released. Analysts have long noted that Mandela’s liberation did not magically end conflict; the early 1990s were marked by intense political competition and violence, and Mandela’s leadership would be tested repeatedly as negotiations advanced amid instability.

In this phase, Mandela’s personal discipline—honed across decades of surveillance and deprivation—became a political asset. He approached politics as an arena in which symbolism must serve structure. He understood that apartheid’s collapse would require both pressure and reassurance: pressure so the state could not stall indefinitely, reassurance so that powerful institutions (business, security forces, conservative white constituencies) would not choose scorched earth.

This balancing act—militancy of purpose, moderation of tone—was not universally popular. Within liberation movements, the distance between the crowd’s emotional urgency and the negotiation table’s incremental pace can become an abyss. Mandela’s job was to prevent that abyss from consuming the transition.

Another difficult reality pressed in: the world’s attention can be fickle. Mandela’s release drew cameras; sustaining sanctions, diplomatic pressure, and material support required a different kind of engagement. That is one reason Mandela moved so quickly into international travel. If global publics had helped make his name a symbol, he intended to return the favor by making their governments participants in South Africa’s future.

The world receives Mandela: Diplomacy as theater, theater as leverage

Mandela’s post-release travel—especially in 1990—was not mere celebration. It was a strategic tour designed to accomplish overlapping goals: to thank allies, to consolidate support for sanctions until apartheid’s legal architecture was dismantled, to raise funds for the ANC, and to position the organization as a legitimate governing alternative rather than a romantic resistance brand. The tour also served an internal purpose: to show South Africans that the ANC had global standing and that apartheid’s claim to represent South Africa internationally had been broken.

A Washington Post account from early June 1990 described the scope of the trip as a major diplomatic undertaking—a multi-week itinerary spanning numerous countries, including a significant U.S. segment featuring high-profile receptions and formal political engagements.

To understand the receptions Mandela received, it helps to look at them in clusters: the African front line and neighboring states; the Nordic and European supporters; and the United States, where Mandela’s presence activated a unique convergence of Black political power, liberal moralism, and Cold War-era ambivalence.

Southern Africa and the continent: Solidarity, burden-sharing, and the cost of being a neighbor to apartheid

Before Mandela was welcomed by parliaments in Europe or motorcades in American cities, he moved through an African diplomatic landscape that had long carried the burdens of South Africa’s conflict. Neighboring and “frontline” states had hosted exiles, endured cross-border raids, and faced destabilization campaigns by Pretoria. Their solidarity was not symbolic; it was lived experience.

Historical summaries of Mandela’s international tour note that it included African countries such as Zimbabwe, Zambia, Tanzania, and Ethiopia—states with their own postcolonial challenges, but also with political identities shaped by anti-colonial struggle.

In these settings, Mandela’s reception was often framed in the language of continental liberation: South Africa’s fight against apartheid was treated as the unfinished business of African decolonization. Leaders and publics saw Mandela not only as a South African figure but as a representation of Africa’s long contest with racial hierarchy and external control.

Yet even among allies there were complexities. Supporting the ANC involved risk. Hosting its leaders could provoke South African retaliation. Some governments also wanted to ensure that South Africa’s transition would not export instability across borders. Mandela had to reassure them, too: that the ANC’s strategy aimed at a democratic state capable of regional partnership, not a revenge project.

The point of these visits was therefore not merely to bask in solidarity but to maintain a coalition whose costs had been real. Mandela’s credibility with these states was immense; his responsibility was to convert that credibility into sustained support during negotiations that might tempt outside observers to withdraw pressure too early.

Sweden and the Nordic model: The reunion and the moral patronage of a small power

In Europe, Mandela’s reception varied by country, but there is a special place in the story for Sweden and the Nordics, where anti-apartheid solidarity had been unusually robust across party lines and civil society.

A South African History Online account of Mandela’s continued tour highlights Sweden specifically, noting that Mandela reunited there with Oliver Tambo, the ANC leader who had spent years in exile and was then recuperating from a stroke. The reunion carried emotional and political weight: it demonstrated continuity between the imprisoned internal leadership and the exiled external leadership, and it placed a spotlight on a European ally that had invested heavily in the anti-apartheid cause.

Sweden’s embrace of Mandela was not the reception of a neutral observer; it was, in many respects, the validation of a long moral stance. For Mandela, that mattered. It reinforced the ANC’s legitimacy. It also offered a template for how international relationships could be built on principle rather than convenience—an attractive idea for a movement preparing to govern a country that would soon need investment, debt management, and reintegration into global markets.

The Nordics also helped frame Mandela as a statesman rather than a militant—without erasing his history, but by emphasizing negotiation and democratic transition. That framing had diplomatic value, especially when Mandela would later face questions—particularly in the United States—about the ANC’s armed struggle and its alliances during the Cold War.

Britain and the contested welcome: Pragmatists, skeptics, and the politics of respectability

In the United Kingdom, Mandela entered a public sphere that had been deeply engaged with anti-apartheid activism, but also shaped by political leaders who had not always embraced the movement.

The British anti-apartheid campaign had been a powerful force in civil society, and Mandela’s name had been an organizing banner for years. But establishment politics were complicated. Thatcher-era conservatism had often been skeptical of sanctions and harsh toward liberation movements, even as public sentiment increasingly favored Mandela’s release. Photographs and retrospective accounts of Mandela’s meetings with British leaders underscore both the symbolic reconciliation and the lingering tensions that characterized parts of Western Europe’s relationship to the ANC.

Mandela’s approach in such environments was typically to accept the welcome without surrendering the argument. He could be gracious while remaining firm that apartheid had to end completely, not cosmetically. He also understood that public receptions—crowds, ceremonies, press conferences—were instruments. Each handshake became a way to normalize the ANC as a future governing party and to isolate hardline apartheid supporters.

The United States: Ticker tape, stadium crowds, and a movement testing America’s conscience

If Europe offered Mandela a stage of moral affirmation, the United States offered something more contradictory: celebration fused with political bargaining, adoration mixed with anxiety, and an especially intense spotlight from Black American communities who had long treated apartheid as a domestic civil rights issue exported abroad.

Mandela’s U.S. tour in June 1990 was organized as a major political event. Contemporary reporting emphasized its scope and strategic aims: to thank supporters, raise funds, and press for the continuation of sanctions.

In New York City, Mandela’s reception became iconic: a ticker-tape parade—an honor typically reserved for heads of state and war heroes—signaled that the city was greeting him as an international liberator. Wire coverage described the exuberance of the welcome and the symbolic force of Broadway’s confetti ritual.

New York’s municipal archives later documented the “Freedom Tour” atmosphere, including Mandela’s presence at major public events and the scale of the city’s embrace, underscoring the extent to which local government and civic identity participated in the symbolism.

In stadiums and large venues—such as the widely remembered rally atmosphere in New York—Mandela’s reception resembled a civil rights revival meeting crossed with statecraft. It mattered that he was welcomed by crowds, not only officials. Mandela’s legitimacy was popular, not merely diplomatic. The cheers were not incidental; they were part of the leverage.

Yet the U.S. tour was also about formal power. Washington Post schedule reporting from June 1990 described a packed itinerary that included meetings with President George H.W. Bush and Secretary of State James Baker, and culminated in a speech to a joint session of Congress.

Mandela’s appearance before Congress, preserved in U.S. public affairs archives and broadcast records, placed him inside an American political ritual typically reserved for allies and world leaders.

The speech and the meetings carried a specific strategic objective: sanctions. Mandela knew that as negotiations began in South Africa, foreign governments—especially powerful economic partners—might look for reasons to normalize relations quickly. Mandela argued, repeatedly, that symbolic reforms were not enough; pressure should remain until apartheid’s legal and institutional structures were dismantled and a credible democratic process was secured. That argument placed him in tension with some American political instincts, particularly among those who prioritized stability, business ties, or Cold War-era relationships.

But the reception he received—from the ticker tape to the congressional platform—showed that Mandela had successfully reframed the debate. He had made it politically costly to treat apartheid as just another foreign policy issue. The struggle had become a question of American identity and moral posture, especially in a period when Black political leadership in the U.S. was asserting itself more forcefully in national debates.

The meaning of the receptions: Mandela as mirror and messenger

Across these countries, the pattern is striking: Mandela was welcomed as both a person and a projection. In Africa, he was part of a continental narrative of liberation. In Scandinavia, he was a vindication of principled internationalism. In Britain, he was a test of whether establishment respectability could catch up to popular morality. In the United States, he was a mirror held up to a superpower that liked to imagine itself as the home of freedom.

Mandela accepted these roles because they served a purpose, but he did not become trapped by them. His genius was to use adoration to buy time and space for negotiations, and to use the world’s affection as a form of insurance against the worst impulses of a threatened apartheid state.

Why February 11, 1990 still matters: Not only freedom, but method

The release of Nelson Mandela is remembered as a triumph of endurance and moral clarity. That is true, but incomplete.

Its deeper significance lies in what it demonstrated about political change at the end of the 20th century: that domestic mass struggle and international pressure could converge; that a state built on racial hierarchy could be forced into negotiation; and that the transition from oppression to democracy would require not just righteous anger but procedural imagination.

Mandela’s own words on the day of his release underscore this. In his Cape Town address, he did not treat his freedom as personal deliverance. He treated it as a phase in a collective project, and he placed negotiations and continued mobilization in the same sentence—as if to insist that diplomacy without pressure was fantasy, and pressure without a political endgame was disaster.

Institutions like the United Nations later framed Mandela’s post-release path—negotiating the end of apartheid with de Klerk, moving toward democratic elections—as a model of political transformation that reshaped global norms around human rights and governance.

Yet it is also important, ethically and journalistically, to avoid turning the release into a fairy tale. Even sympathetic reflections note that Mandela’s freedom did not end violence and that the years that followed involved profound turbulence. The point is not to diminish the moment, but to understand its courage: Mandela walked out not into peace, but into responsibility.

The day after the celebration: The unfinished work that the gate exposed

In the years since Mandela’s death, the release has been memorialized repeatedly—as anniversary content, as classroom shorthand, as a global parable. The Nelson Mandela Foundation has marked the anniversaries by emphasizing that the walk to freedom was a beginning, not a finish: a stage in a longer effort to align political ideals with social realities.

That framing is instructive, because it reminds us what Feb. 11, 1990 ultimately revealed: that liberation is not an event but a process. The prison gate offered a clean narrative arc—oppression, endurance, release. But Mandela’s greatness was not confined to surviving prison; it was expressed in what he did after the cameras captured his first steps.

He insisted on political inclusion without surrendering moral judgment. He pursued negotiations without fetishizing compromise. He accepted international applause without letting it substitute for structural change. And he understood that, in modern politics, images can move people—but only strategy can move institutions.

That is why the release of Nelson Mandela still matters. It remains one of the rare moments when the world watched a person step from captivity into history—and then watched, more slowly and less comfortably, as he tried to turn that history into a livable country.

And it is why the image at the gate endures: not simply because it shows a man becoming free, but because it shows a man walking toward the most difficult part of freedom—what comes next.

More great stories

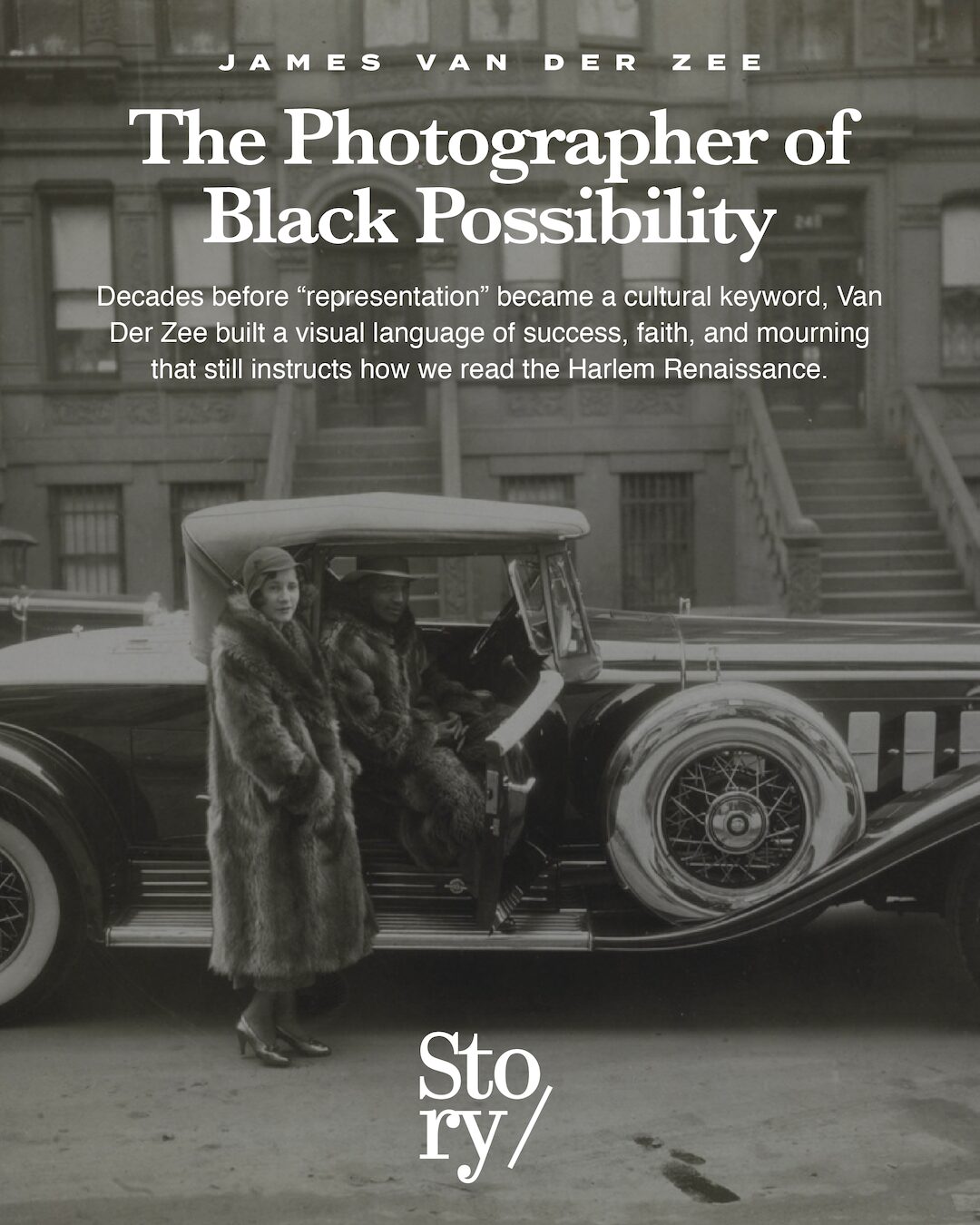

James Van Der Zee: The Photographer of Black Possibility