Van Der Zee’s photographs endure partly because they are beautiful, but beauty is not the endpoint. The deeper reason is that they preserve an argument: that Harlem contained multitudes, that Black life contained elegance and complexity, and that a people denied full citizenship still insisted on full portraiture.

Van Der Zee’s photographs endure partly because they are beautiful, but beauty is not the endpoint. The deeper reason is that they preserve an argument: that Harlem contained multitudes, that Black life contained elegance and complexity, and that a people denied full citizenship still insisted on full portraiture.

By KOLUMN Magazine

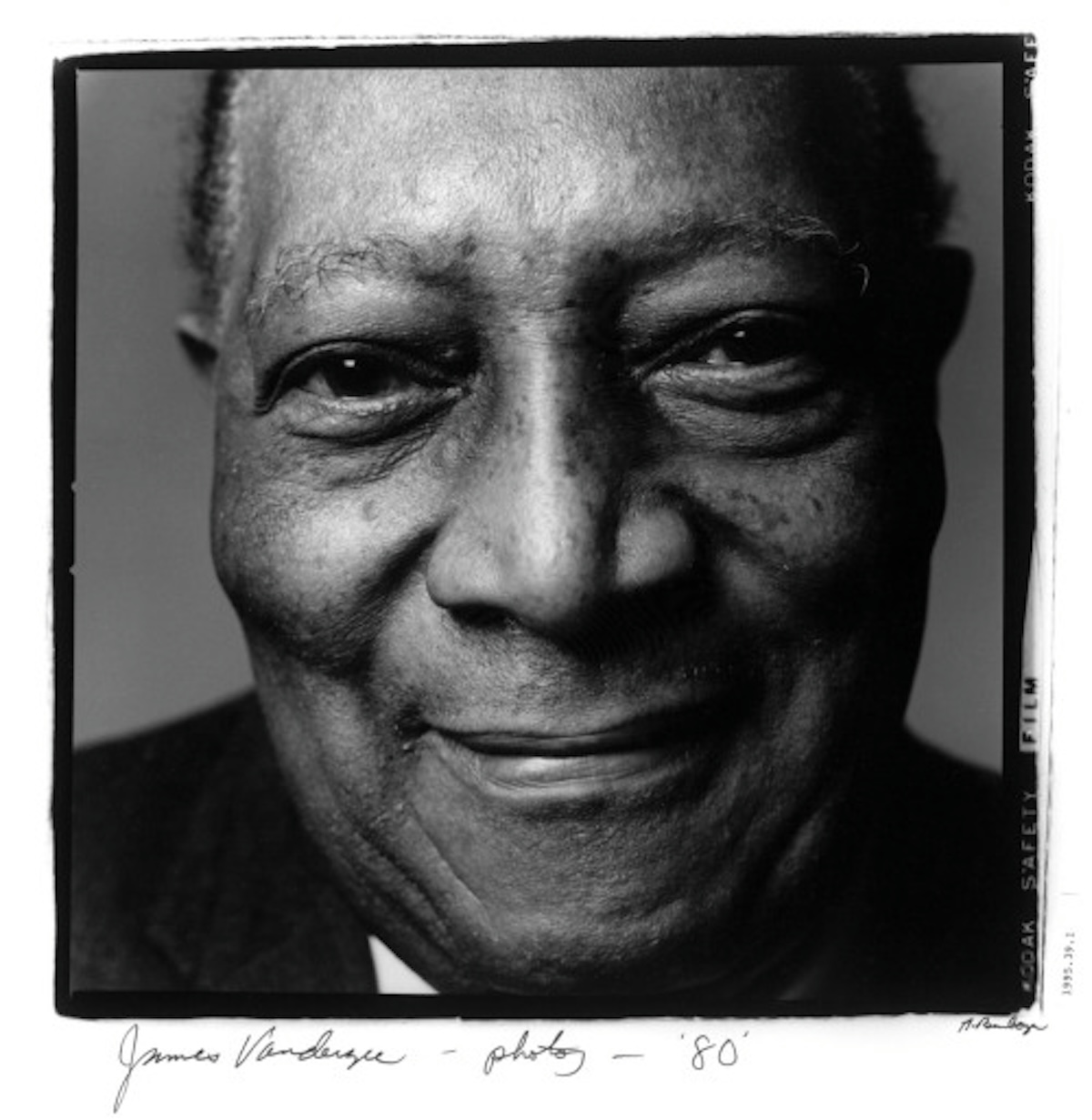

There are photographers who chase the world as it spills past them, grabbing at the blur of the street, the accident, the unrepeatable collision of bodies and light. And then there are photographers who build a room—a controlled space with backdrops, props, a chair angled just so—where the world can be composed rather than merely captured. James Van Der Zee belonged to the second tradition, yet what he produced has the documentary force of the first. Across a career that spanned more than eight decades, Van Der Zee’s portraits formed one of the most expansive visual chronicles of Black life in twentieth-century Harlem: its rituals and social clubs, its ministers and dancers, its soldiers and shopkeepers, its matrons and children, its strivers and its settled. His images do not simply show Harlem. They show Harlem seeing itself.

To call Van Der Zee a “Harlem Renaissance photographer” is accurate, but it can also be reductive, like labeling a cathedral by the decade it was built. He did photograph the Harlem Renaissance, and his studio became a place where the neighborhood’s emerging middle class and cultural elite marked their arrivals—new suits, engagements, church anniversaries, lodge memberships, athletic teams, victory parades. Yet his practice also reached backward into the early years of the Great Migration and forward into the late twentieth century, when museums and publishers “rediscovered” what Harlem residents had long known: that a local portraitist had been quietly producing art and history at once.

Van Der Zee’s significance sits in that duality. He was a craftsman who made a living—often an uneven one—photographing paying customers. He was also a visual theorist of respectability, a stylist of Black modernity, and, at times, a subtle manipulator of reality, retouching negatives, combining exposures, adding halos of light, inserting symbolic elements that turned a portrait into a small allegory. What results is not an unbiased mirror of Harlem so much as a sustained argument against how America insisted Harlem should be seen. The argument is made with velvet drapes, polished shoes, manicured hands, crisp uniforms, flowers, and, in the most haunting sequence of all, the softening of death into a final tableau of care.

Lenox beginnings, Harlem ambitions

James Augustus Van Der Zee was born in 1886 in Lenox, Massachusetts, a small town that would later be associated with Gilded Age leisure and Berkshire cultural institutions. Long before Harlem, there was the domestic laboratory: the teenage Van Der Zee improvising photographic processes, experimenting with the camera’s capacity to translate the familiar into something formal. He was also deeply musical—an early ambition that matters because it suggests how he understood performance, timing, and arrangement, the same instincts that would later govern his portraits. He arrived in Harlem in the early twentieth century as one of countless Black Americans moving toward northern cities for work and possibility.

Harlem, by the time Van Der Zee opened his studio, was becoming both a place and an idea. It was shaped by migration and by real estate patterns, by the rise of Black institutions and the grinding force of segregation, by the appetite for nightlife and the seriousness of political organizing. Van Der Zee’s career would be braided into those developments. He was not simply documenting a neighborhood’s aesthetics; he was participating in the making of a new public image of Black urban life. The portrait studio was one of the technologies of that image—like the newspaper, the church program, the parade, the cabaret, the fraternal lodge. It offered a stage where private aspiration could be translated into public proof.

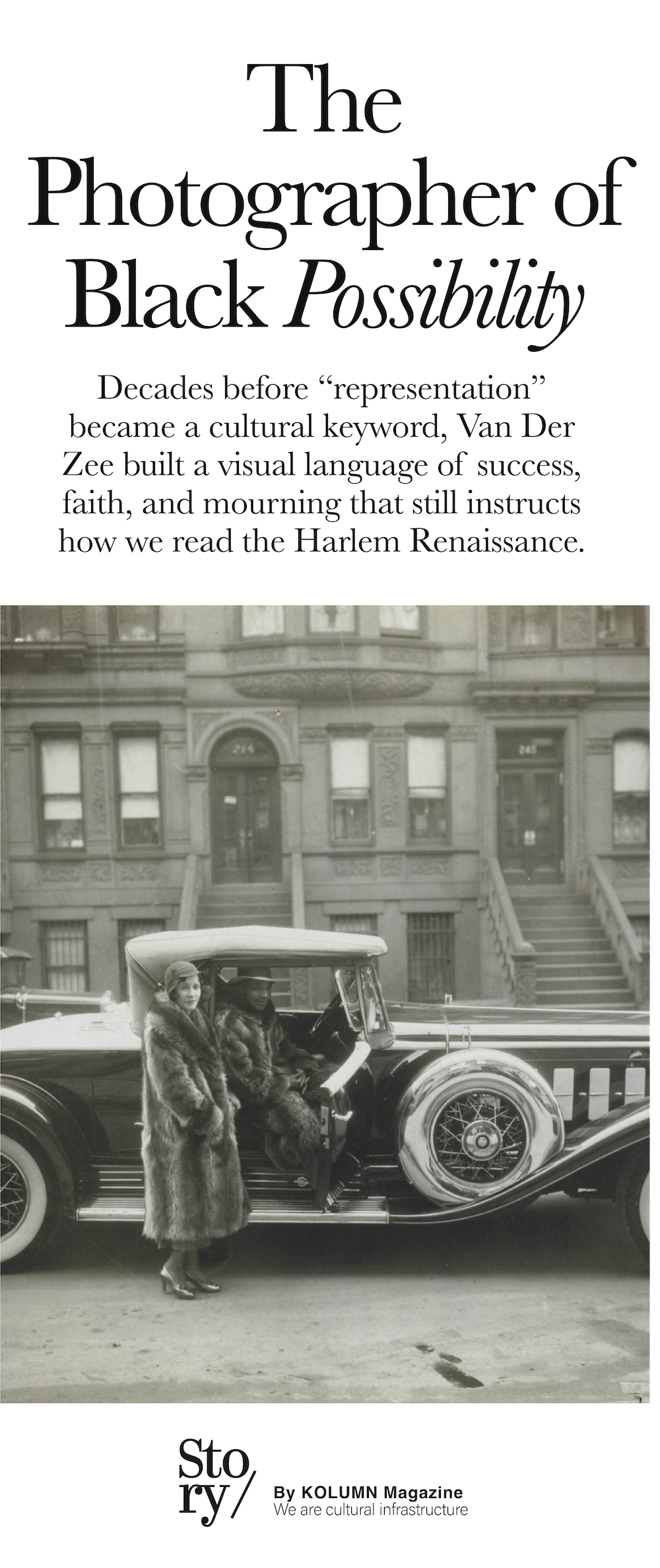

In 1916, Van Der Zee opened what became a cornerstone of his Harlem practice, a studio operation that evolved through different names and partnerships. Sources emphasize that Harlem residents came to mark special occasions and to craft a cosmopolitan self-presentation in front of his lens. That phrasing—cosmopolitan—is not a decorative adjective. It is the story. The sitters arrive in his photographs dressed for a world that mainstream American culture often denied them: furs, hats, tailored suits, polished shoes, beaded dresses, military uniforms, choir robes, club jackets. Van Der Zee’s Harlem is not a slum postcard; it is a society portrait.

The studio as a civic institution

A portrait studio can be a small business, but in certain communities, at certain moments, it becomes something more like an archive in real time. Van Der Zee’s studio—elegantly furnished, strategically lit—was a civic institution for a neighborhood constructing itself under pressure. The National Gallery of Art, in describing his work, stresses the care with which he composed images and how his photographs conveyed “the personalities, aspirations, and spirit” of the sitters. The Studio Museum in Harlem frames his practice as comprehensive, moving “from the everyday to the aspirational.”

Those words—aspirations, aspirational—often appear in contemporary writing about Van Der Zee, partly because they unlock a crucial truth: his portraits are collaborative performances. The sitter arrives with a desired self. The photographer supplies the means to make that desire legible. Backdrops and props do not merely decorate; they locate the subject in a narrative of arrival. A chair suggests stability. A column suggests grandeur. A telephone suggests modern connectivity. A car suggests mobility and wealth. In an era when caricatures of Black inferiority circulated freely in popular culture, these portraits functioned as counter-propaganda, intimate but also public-minded. A family photograph could be mailed, displayed, saved, inherited. It could travel, carrying evidence of a life made.

The Washington Post has described Van Der Zee’s role in spreading an image of “a sophisticated, cosmopolitan Harlem,” an image that stood against racist caricature. Even when you do not know the sitter’s name, you can read the social grammar: here is a person making a claim on modernity.

Technique as rhetoric

Van Der Zee’s artistry is inseparable from technique, and his technique was never only technical—it was rhetorical. He worked in a period when photography was shifting from an elite craft to an increasingly accessible medium, and portrait studios competed on both price and polish. Van Der Zee’s polish came from the darkroom as much as the sitting. He retouched negatives, refined skin tones, softened blemishes, heightened highlights on jewelry, and calibrated shadows to create a sheen that reads, in hindsight, like a deliberate aesthetic of Black glamour. Scholarly analysis of his prints underscores the technical sophistication of his portrait photographs and the material decisions embedded in them.

He also used effects that complicate the simple idea of the photograph as truthful capture. Double exposures and composite imagery appear across his work, sometimes subtly, sometimes with the obvious intention of adding symbolic meaning. In this, he aligns with older portrait traditions—painted portraits, memorial images—where representation is not merely what the eye sees but what a community believes ought to be preserved.

The crucial point is that Van Der Zee’s manipulations are not lies in the tabloid sense; they are translations. He is translating dignity into an image-world that has historically refused it. The retouching becomes a politics: not the politics of hiding reality, but the politics of refusing degradation.

Garvey, organizations, and the visual language of power

The Harlem Renaissance was not only art; it was infrastructure—clubs, churches, mutual aid societies, political organizations, and parades that announced a people’s seriousness to itself. Van Der Zee photographed these institutions with an insider’s eye. His work documenting Marcus Garvey’s movement, including members and activities of the Universal Negro Improvement Association, has been widely noted as part of his portrait of Harlem’s political and social life. In these images, uniforms and banners are not props; they are emblems of collective aspiration, proof that Black modernity was organized and self-authored.

He also photographed soldiers and civic ceremonies, including moments associated with Black military units and public celebration. The larger story is that Van Der Zee’s camera was frequently turned toward people who were shaping public life, whether from a pulpit, a stage, a club podium, or a parade route. In doing so, he helped encode what authority looked like in Black Harlem—an authority that did not rely on white approval.

Everyday life, stylized

What is striking, looking across Van Der Zee’s body of work as it appears in museum collections and exhibitions, is the range of social space it covers. The Museum of Modern Art’s listing of his works suggests not only society portraits but athletic teams, baptism celebrations, beach scenes, and nightclub life—images that place Harlem’s striving beside its leisure, its faith beside its fun. The National Gallery likewise emphasizes that his photographs include community groups and scenes that together provide a glimpse into Harlem’s rich social life as it became a center of American culture.

If you are accustomed to documentary photography that privileges hardship, Van Der Zee can feel almost evasive at first glance. Where is the overcrowding? Where is the struggle? But the absence is instructive: he was making a different kind of record, one that insisted that Black life could not be reduced to suffering, even in an era when suffering was abundant. He photographed what people wanted remembered. That does not mean hardship was absent from Harlem; it means that Harlem residents also had a profound desire to be recorded in their full personhood, including joy and pride.

Death, memory, and “The Harlem Book of the Dead”

The most emotionally complex portion of Van Der Zee’s legacy may be his funerary photography, gathered and published decades later as The Harlem Book of the Dead. In these images, the portrait studio’s aesthetic logic crosses into mourning: the deceased presented with care; mourners arranged; caskets surrounded by flowers; the scene lit and composed to make grief bearable, and to frame death as a passage witnessed by community. Contemporary reflections emphasize how Van Der Zee’s funerary images transform the harshness of death into a dignified, even dreamlike, visual language.

The book itself is polyvocal. Writing around the reissued edition underscores its structure as a chorus: an interview with Van Der Zee, poetry, and a foreword by Toni Morrison. That Morrison connection matters beyond literary prestige. Morrison’s work is fundamentally concerned with how the past inhabits the living, how memory becomes both wound and inheritance. Van Der Zee’s funerary portraits, in that sense, are Morrison’s territory: the place where the living arrange a scene to speak to the future, where love becomes a document.

The Atlantic, in an essay about Morrison’s archive, notes that Morrison was disturbed and inspired by Van Der Zee’s funerary portraiture, suggesting the photographs’ capacity to trouble even a writer renowned for confronting the darkest parts of American history. Van Der Zee’s images insist that mourning is not only personal; it is cultural production.

Decline, near-erasure, and the economics of a changing medium

Van Der Zee’s career was not a steady ascent into recognition. Like many studio photographers, his livelihood depended on customers, and the economics of photography shifted as technology became cheaper and more widely available. The Great Depression, changes in consumer spending, and the spread of personal cameras all altered the portrait market. Some accounts describe periods of hardship and decreased demand in the mid-century years, a common fate for photographers whose work was deeply tied to a community’s ability to pay for formal portraiture.

This is part of the broader American pattern: cultural labor performed for and within Black communities often becomes visible to mainstream institutions only after long stretches of neglect. Van Der Zee remained known in Harlem, but the wider art world treated him as peripheral until it suddenly did not.

1969 and the paradox of “rediscovery”

The hinge point in Van Der Zee’s public reputation is frequently traced to 1969, when his work appeared in the Metropolitan Museum of Art’s exhibition Harlem on My Mind: Cultural Capital of Black America, 1900–1968—an exhibition remembered as much for controversy as for content. Multiple sources note that this was a moment of rediscovery for Van Der Zee. But it is equally important to name what was being “rediscovered” and by whom. Harlem had not lost Van Der Zee. The mainstream museum world had failed to see the cultural centrality of the work until it wanted Harlem as a subject.

The Met itself has published institutional reflection on Harlem on My Mind, describing the show’s multimedia approach—photographs, clippings, soundscapes—and the protests sparked in part because it excluded paintings and sculpture by Black artists. The exhibition, in other words, turned Harlem into an anthropological environment while sidelining Harlem’s fine artists, replicating an old hierarchy: Black culture as documentary material, not as high art.

And yet, within that flawed framework, Van Der Zee’s photographs landed with force. They were not simply illustrations of Harlem; they were Harlem’s self-portrait. Viewers confronted images that contradicted what many Americans believed about Black urban life. That contradiction was both aesthetic and political, and it helped propel Van Der Zee into a late-life surge of recognition.

The Washington Post’s later writing about Van Der Zee suggests the depth of his cultural authority in the interwar years—“If you were black and ambitious in Harlem between the wars, you had to have your picture taken” by him—an assertion that reads like folklore and civic fact combined. What museums called “rediscovery” was, in Harlem, closer to acknowledgment.

Late years, enduring eye

Van Der Zee lived until 1983, long enough to see his work enter the bloodstream of American cultural history. Accounts of his death note that he was celebrated as both artist and historian. His longevity matters because it complicates the romance of the “lost genius.” Van Der Zee was not a ghost discovered in an attic after death; he was present, living, and, in many cases, able to speak about his own work as institutions began to reframe it.

The late years also connect Van Der Zee to subsequent generations, not only as influence but as participant. The fact that his camera could move from photographing Harlem’s interwar social clubs to photographing figures associated with later twentieth-century art worlds underscores how his eye was not trapped in the 1920s. He understood style as a living language.

Archives, stewardship, and the ethics of ownership

If Van Der Zee’s portraits are a community’s self-authored image, then the question of where those images live is not merely administrative; it is ethical. The New York Public Library’s Schomburg Center has holdings related to Van Der Zee’s photographs, emphasizing their value in representing multiple aspects of his work and Harlem life. Museums such as MoMA continue to exhibit and contextualize his prints.

In the last several years, the Metropolitan Museum of Art has publicized the creation of the James Van Der Zee Archive, describing a vast body of prints, negatives, and studio ephemera. The language used—archive, ephemera, equipment—matters because it signals that Van Der Zee’s work is not only individual masterpieces but a whole ecosystem of production: the business tools, the backdrop decisions, the material history of how a community made itself visible.

Archival stewardship, however, is always a negotiation. The history of Black cultural artifacts in American institutions is full of extraction and belated celebration. The best institutional work now attempts partnership and accountability, but the underlying question remains: how do you preserve a community’s visual memory without stripping it of context or control?

Van Der Zee’s legacy is inseparable from that question. His sitters paid for images that were often intended for family circulation and community display. Over time, those images become art objects traded, exhibited, and monetized in markets far removed from the original transaction. That transformation is not unique to Van Der Zee; it is the fate of much vernacular photography when museums decide it is canonical. But because Van Der Zee’s work is so deeply about Black self-fashioning under racism, the politics of who profits and who narrates become especially charged.

Influence: from Harlem’s parlors to contemporary portraiture

Van Der Zee’s aesthetic—the controlled light, the glamour, the dignity, the sense of portraiture as a contract between sitter and photographer—echoes through later Black photography. One can see it in the insistence on beauty as a form of resistance, in the idea that the studio can be a site of authorship rather than extraction. Contemporary photographers who stage their subjects, who use props and backdrops to interrogate identity, who treat fashion and pose as language, operate in a world Van Der Zee helped make possible.

There is also a direct line from his work to present-day conversations about “Black joy” and representation. Van Der Zee was making images of Black joy and Black pride before those phrases became cultural shorthand. His photographs offer a corrective to a journalism and documentary tradition that has too often made Black suffering its primary visual grammar. That corrective is not naïve. Van Der Zee knew what he was doing. His Harlem is aspirational because aspiration itself was historically radical.

Even when his work touches the somber—especially in the funerary photographs—it does so in a way that emphasizes ritual, care, and communal presence. In that sense, his archive is not only about how people lived but how they wished to be remembered.

Harlem, myth, and the problem of nostalgia

Any long look at Van Der Zee risks falling into nostalgia. The clothes are exquisite. The pose is composed. The gaze is confident. It can be tempting to turn Harlem into a lost kingdom of elegance, untroubled by the structural realities of segregation, labor exploitation, housing discrimination, and state violence.

But Van Der Zee’s portraits are not proof that Harlem was free of hardship. They are proof that Harlem had a sophisticated culture of self-presentation in spite of hardship. They show the creativity required to build a dignified public image in a country committed to Black degradation. They also show the internal complexity of class within Black communities: the presence of upward mobility, the formation of a Black middle class, the role of churches and fraternal organizations in structuring social life.

The tension is part of what makes the work valuable. Van Der Zee’s photographs do not ask viewers to pity Harlem. They ask viewers to recognize Harlem as a site of modernity.

The journalist’s problem is that those two impulses—recognition and romanticization—can blur. The ethical approach is to treat Van Der Zee’s images as what they are: collaborative constructions shaped by a specific economy and desire. His sitters are not naïve victims of the camera; they are active authors of their image, hiring a photographer to help write it.

A documentary dinner party and the late-twentieth-century afterlife

The afterlife of the Harlem Renaissance has become its own cultural industry—books, films, exhibitions that return to the era as a touchstone. Van Der Zee appears in that afterlife not only through his images but, in at least one recent documentary context, as a living participant in recollection. A Guardian review of Once Upon a Time in Harlem describes a 1972 gathering of Harlem Renaissance figures, including Van Der Zee, reflecting on the movement and its legacy. The significance here is subtle but important: Van Der Zee was not merely the one who photographed the Renaissance; he was a figure within its social world, present to narrate it later.

That presence reinforces what his portraits already suggest: the Harlem Renaissance was not a static period label but a network of relationships and institutions that extended across decades. Van Der Zee’s longevity allowed him to witness the transformation of Harlem—from renaissance symbol to battleground of urban policy to site of nostalgia and gentrification—and to watch as museums reframed the neighborhood’s history through institutional lenses.

The meaning of Van Der Zee now

Why does James Van Der Zee matter in 2026, beyond the art-historical certainty that he belongs in the canon? He matters because the central conflict of his work—the battle over representation—has not ended. Communities still fight to control how they are seen. The line between documentation and caricature remains contested terrain. And the portrait, as a technology of self-fashioning, is more ubiquitous than ever: the smartphone selfie, the curated feed, the personal brand.

Van Der Zee offers an earlier, more deliberate model. His portraits remind us that images are made, not simply taken. They show how aesthetics can be a form of social defense, and how style can carry political weight. They also complicate any simplistic idea of authenticity. In Van Der Zee’s studio, authenticity was not the unguarded snapshot; authenticity was the self one chose to present, the self one needed the world to recognize in order to survive and advance.

Institutions continue to deepen scholarship around his techniques and materials, reinforcing that his work can be studied with the seriousness given to any major artist. At the same time, the ongoing organization of his archive and the continued circulation of his images in exhibitions and publications raise necessary questions about context, access, and community memory.

Van Der Zee’s photographs endure partly because they are beautiful, but beauty is not the endpoint. The deeper reason is that they preserve an argument: that Harlem contained multitudes, that Black life contained elegance and complexity, and that a people denied full citizenship still insisted on full portraiture.

More great stories

James Heming: Paris Trained, Virginia Owned