A truthful retelling of the Kentucky Derby demands. It demands precision about the facts: the date, the distance, the purse, the crowd, the people, the time. It demands honesty about the context: slavery’s legacy in horse culture, Reconstruction’s fragile openings, Jim Crow’s closing fist.

A truthful retelling of the Kentucky Derby demands. It demands precision about the facts: the date, the distance, the purse, the crowd, the people, the time. It demands honesty about the context: slavery’s legacy in horse culture, Reconstruction’s fragile openings, Jim Crow’s closing fist.

By KOLUMN Magazine

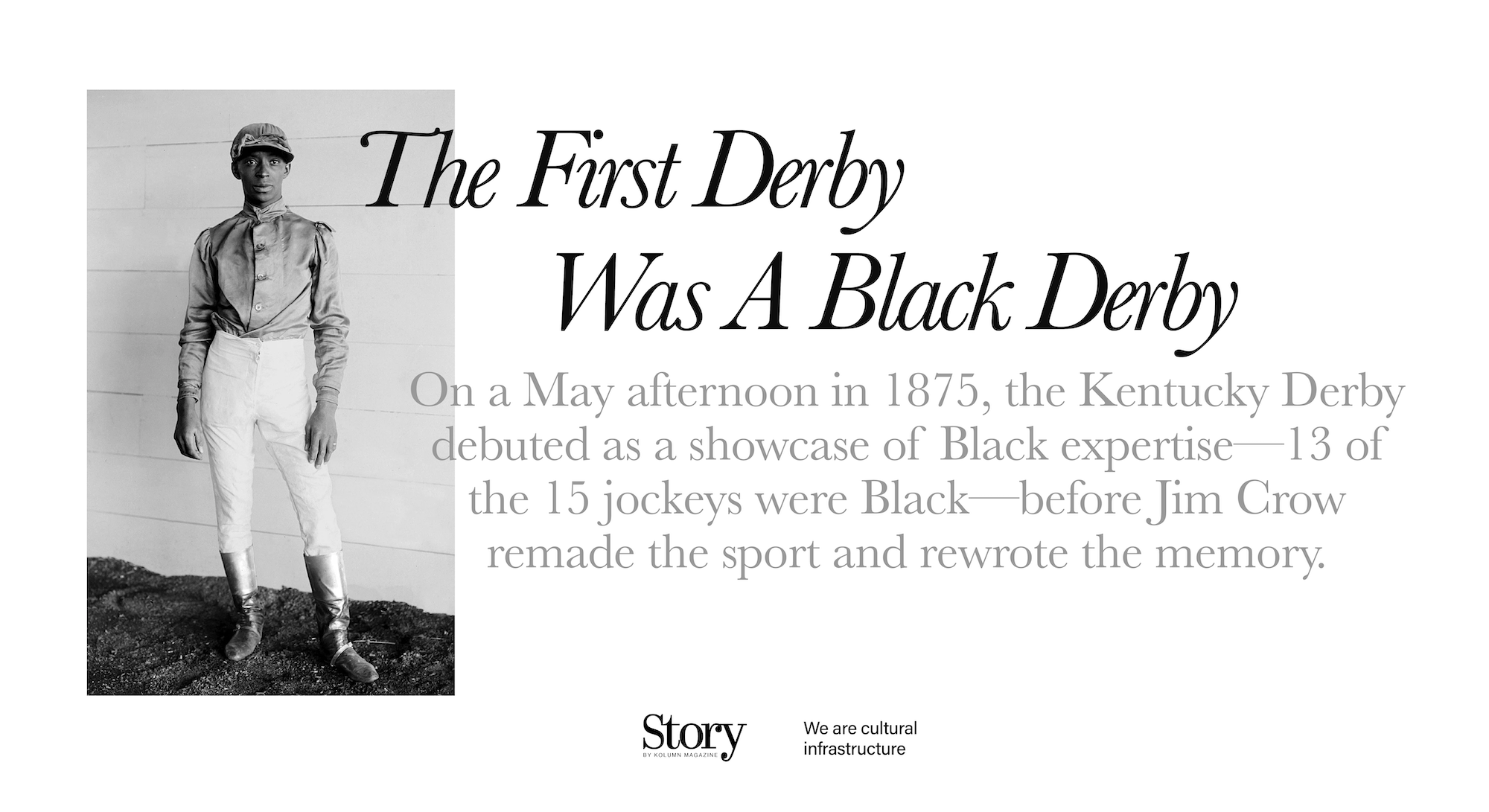

On May 17, 1875, Louisville unfurled a new kind of spectacle. Ten thousand people, give or take, poured toward the Louisville Jockey Club grounds—what the city would later call Churchill Downs—to watch fifteen three-year-old thoroughbreds run a mile and a half. The day reads now like the opening line of an American ritual: a springtime crowd, a single race, a winner crowned into instant legend. Yet if you freeze that scene and let your eyes adjust, what emerges is not the story modern Derby mythology prefers to foreground. Thirteen of the fifteen jockeys who climbed aboard those horses were Black.

That fact—at once plain and startling to contemporary viewers accustomed to a Derby starting gate dominated by riders from Latin America and a sport whose marquee stages rarely feature Black athletes—was not a curiosity in 1875. It was, in many ways, the baseline. In the decades before and after the Civil War, Black horsemen had been the backbone of Southern racing: grooms, exercise riders, stable hands, trainers, and jockeys, carrying forward a body of knowledge that had been demanded under slavery and then repurposed, fitfully and precariously, into paid expertise during Reconstruction.

The inaugural Kentucky Derby, then, is best understood not only as the birth of a race but as a snapshot of an American contradiction: a public celebration built on Black skill at the precise historical moment when the nation was arguing—often violently—about what freedom would mean, and for whom. In that frame, the first Derby becomes something larger than “the most exciting two minutes in sports.” It becomes a scene in a longer drama about labor, ownership, celebrity, and erasure; about how Black excellence could be indispensable and still disposable; about how the people closest to the animal—those who understood its nerves and lungs and limits—could be central to a sport’s rise and nearly absent from its modern image.

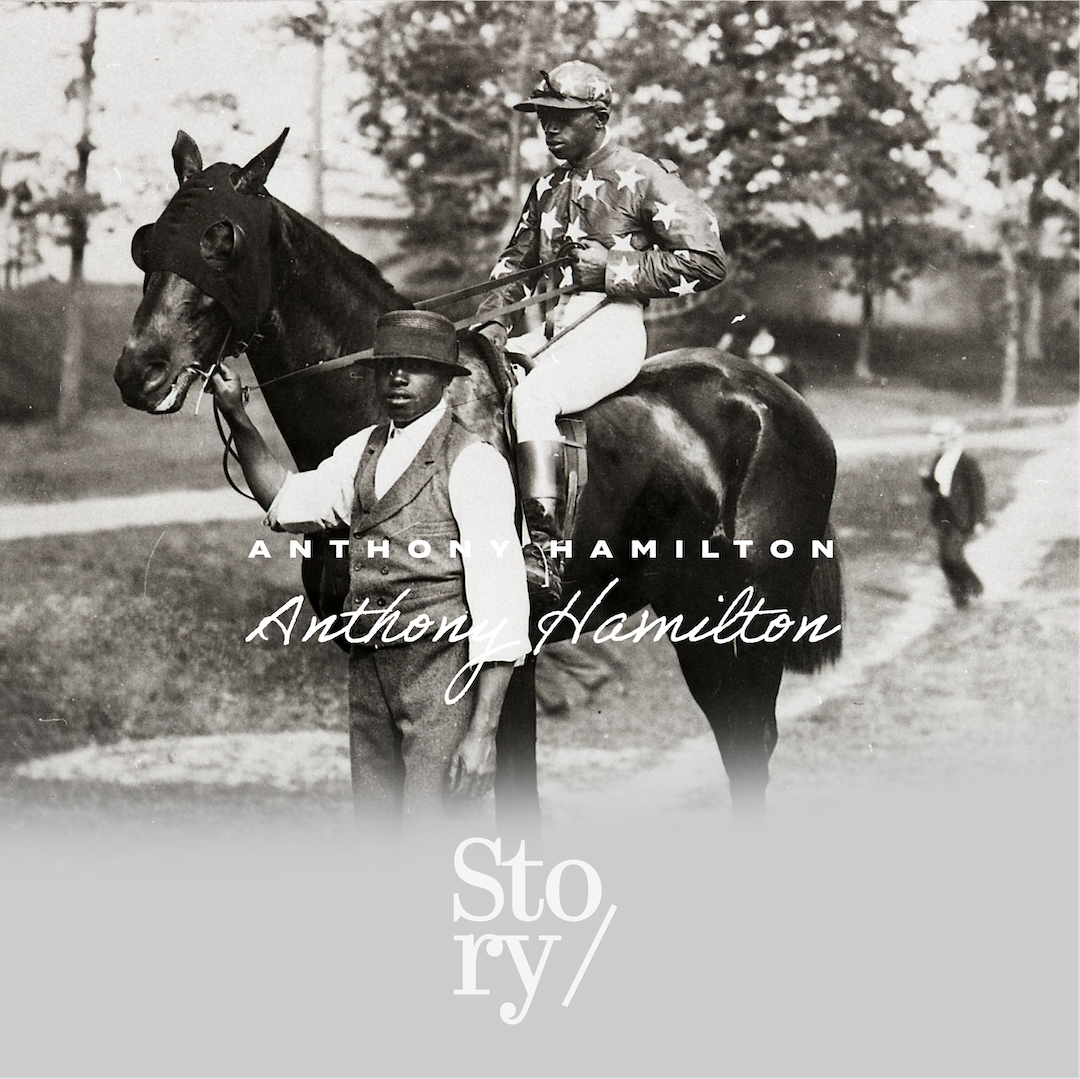

The winner that day was a chestnut colt named Aristides, owned by H. Price McGrath and ridden by Oliver Lewis. Aristides won by about two lengths in 2:37.75, a time widely reported as extraordinary for the distance. Lewis became the first Derby-winning jockey; his trainer, Ansel Williamson, was also Black, a horseman whose career had begun in slavery and extended into the sport’s highest tiers.

And yet even the origin story contains the seeds of how Black agency was often constrained inside white-controlled systems. Multiple accounts of the 1875 race describe a strategic design in which Aristides was intended to set a punishing pace to benefit a stablemate, Chesapeake—McGrath’s other entrant—who was favored by some bettors. In that telling, Lewis was supposed to be a “rabbit,” a role that can sound like a footnote until you notice what it implies: even when a Black jockey held the reins, the architecture of profit and prestige still belonged elsewhere.

That day, the plan—if it was the plan—fractured. Chesapeake did not deliver the late charge the strategy required. Aristides, driven by Lewis and trained by Williamson, did. The “little red horse,” as later retellings would call him, crossed first, and the inaugural Derby produced its first paradox: a race founded in part to import European aristocratic pageantry to Kentucky ended up enshrining a victory that depended on Black expertise.

A race imported from Europe, built in a Reconstruction America

Meriwether Lewis Clark Jr., the grandson of William Clark of the Lewis and Clark expedition, is generally credited as the driving force behind the Derby’s creation. He traveled in Europe in the early 1870s and, by several accounts, drew inspiration from England’s Epsom Derby and France’s Grand Prix de Paris—events that blended sport with social theater and helped the upper classes see themselves on public display. Back in Louisville, Clark sought to build a track and a signature race that could rival those classics, raising money and founding the Louisville Jockey Club. The track sat on land associated with the Churchill family—hence the name that would eventually stick.

But the Europe-inspired aspirations of the Derby met an American racing reality shaped by slavery and its aftermath. Thoroughbred racing in the South had long been a sport of elites. Horses were expensive, and the track—like the plantation—was a stage on which wealth and power performed itself. Yet the daily intimacy with horses, the handling, feeding, grooming, and conditioning, as well as the dangerous athletic act of jockeying, had often been delegated to enslaved Black men and boys.

The logic was brutally practical. Owners who held human beings as property also treated horses as valuable property; they wanted their best animals cared for by people who could be compelled to work with total, relentless attention. Over time, a knowledge system grew in the stables—how to calm a nervous colt, how to read a stride, how to understand the difference between a horse that was stubborn and a horse that was hurting. After emancipation, much of that expertise did not vanish. It followed the horses.

In the 1870s, the United States was still living in the unsettled wake of the Civil War. Federal protections for Black citizenship were being contested in law and in blood; white supremacist violence operated as an unofficial counter-government; and in many places, Black people negotiated “freedom” inside economic systems designed to keep them dependent. Horse racing did not sit outside this history. It absorbed it. The track offered something rare: a public arena where Black skill could translate into wages, mobility, and sometimes fame. But it also remained entangled with white ownership and white-controlled institutions.

The inaugural Derby illustrates that tension in its personnel. Oliver Lewis, the jockey who rode Aristides, was a young Black Kentuckian. Many retellings describe him as 19; a Washington Post account notes census evidence and other records suggesting he was already a veteran rider despite his youth, with the physical lightness that racing demanded. His trainer, Ansel Williamson, belonged to an older generation—born enslaved in Virginia in the early 1800s, building a reputation as a trainer first in the South and then in Kentucky, navigating the shift from prewar heat racing to newer “dash” formats.

In other words, the first Derby was not merely a “diverse” field by some modern metric. It was a field that reflected who, in that moment, possessed the most hard-won practical knowledge about racing in Kentucky and the broader South.

Thirteen of fifteen: What the number does, and doesn’t, tell you

The statistic that has become a kind of headline—thirteen of fifteen jockeys were Black—appears in mainstream historical accounts, cultural reporting, and scholarship. Smithsonian Magazine, History.com, the Kentucky Historical Society’s public history writing, and academic work published through the National Bureau of Economic Research all state that thirteen of the fifteen jockeys were African American.

There is, however, a wrinkle that matters for journalists: some sources have reported different counts. The Library of Congress, in a “Today in History” entry about May 17, states that fourteen of the fifteen jockeys were African American. The existence of that discrepancy does not weaken the larger truth—Black riders overwhelmingly dominated the inaugural field—but it does hint at the historical conditions under which these stories were recorded and transmitted. Documentation from the 1870s is incomplete, sometimes inconsistent, and often filtered through institutions that did not prioritize accurate, respectful accounting of Black lives. When Black excellence is treated as unremarkable in its own moment and then inconvenient in later retellings, even counting can become unstable.

What is stable is the shape of the moment: the first Derby’s labor and athletic front line was overwhelmingly Black. The race was public; the contribution was visible; the later forgetting was not an accident.

If you want to understand why the inaugural Derby looked the way it did, you need to understand how American racing worked in that era and who controlled it. Owners like McGrath had the capital. They selected horses, hired trainers, and placed bets. The Louisville Jockey Club controlled the grounds and the social setting. Yet the decisive act—the split-second judgments at speed, the feel for pace, the ability to keep a horse balanced under pressure—sat with the jockey. In a world where a professional sports labor market was just beginning to take a recognizable form, jockeys were among America’s earliest professional athletes. Ebony, in reflecting on the history of Black jockeys, underscores this early dominance and the later fade from visibility.

The inaugural Derby is, in that sense, an early scene of Black athletic celebrity in the United States—one that complicates the standard story in which integration is imagined as a one-way march forward. Here the narrative runs backward: Black riders were central, then excluded; celebrated, then erased.

Aristides, Oliver Lewis, and the “rabbit” who didn’t stop running

Aristides’ victory is often retold as a straightforward triumph: the colt surged, the jockey urged, the crowd roared. In modern Derby culture, origin stories are frequently scrubbed into clean parables. But the first Derby, as chronicled by later historians and racing institutions, carries the smell of gambling, strategy, and manipulation—features that were not side shows but core ingredients in 19th-century racing culture.

Accounts collected and recirculated through racing historians describe McGrath’s interest in betting and a strategy that hinged on Aristides setting a fast early pace to aid Chesapeake, another McGrath horse. This is the kind of detail that can be sensationalized if handled crudely. The deeper point is structural: the jockey’s labor was frequently directed toward an owner’s financial plan. In an auction-pool betting environment—an early format in which people bid for the right to place wagers on a horse—the incentives to manipulate outcomes could be intense.

Oliver Lewis, riding Aristides, reportedly executed the early-pace role, pushing the field and keeping the tempo honest. Yet the race did not unfold as the strategy demanded. Chesapeake—expected to be the beneficiary—did not arrive in time. Aristides and another horse, Volcano, fought for the lead. Lewis, in the final stretch, rode for the line and won.

There is a human drama here that deserves more than a footnote. Imagine being a young Black jockey in 1875 Kentucky, operating in a sport where your physical risk is constant and your autonomy is conditional. Imagine being told you are the “setup,” not the star. Then imagine the moment when the race itself makes your supposed role obsolete. Lewis could not stop Aristides from being the best horse that day. He could only ride what was under him.

Lewis’ time—2:37.75—became part of the record, and the winner’s share of the purse, the trophies, and the headlines flowed upward through the sport’s hierarchy. Lewis’ biography after the Derby is thinner than it should be for an inaugural champion. Various accounts note that he did not ride in another Kentucky Derby and later left racing, turning to other work. That thinness is not simply a matter of personal choice. It is also a reflection of what the historical record tended to preserve: owners, institutions, winning horses—often more readily than the Black riders whose bodies, instincts, and courage made the spectacle possible.

Ansel Williamson and the long arc from slavery to Hall of Fame

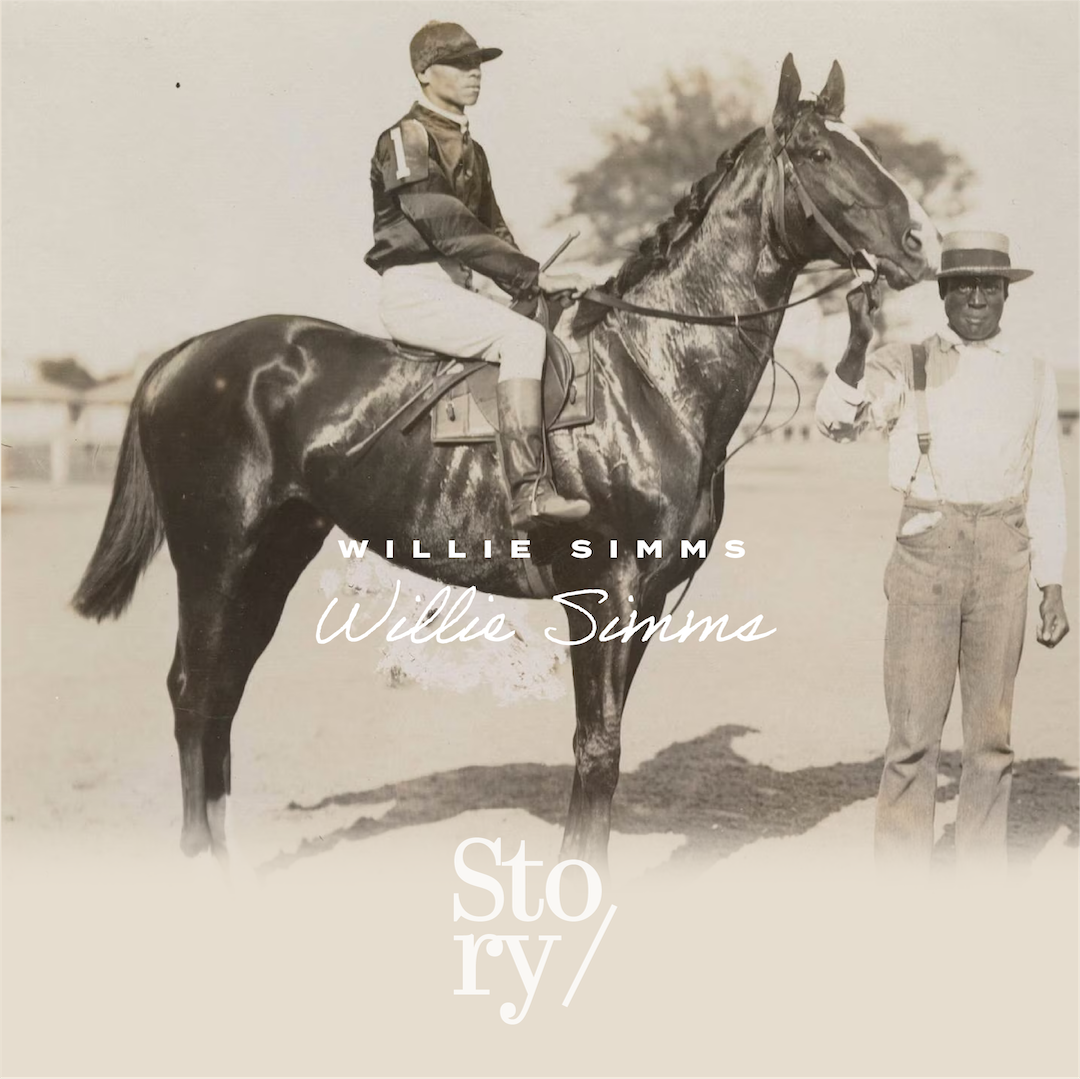

If Lewis’ life is partially obscured, Ansel Williamson’s career offers a broader view of how Black mastery of horse culture developed and was leveraged across eras. Williamson was born enslaved and became one of the most accomplished trainers of his time, spanning a period of racing transformation. The National Museum of Racing and Hall of Fame notes that his career bridged the older era of grueling multi-mile heat races and the later popularity of single-run “dash” races.

Williamson trained not only Aristides but other major winners, and he was inducted into the Hall of Fame in 1998. His story has also been revisited in modern journalism, including the Washington Post, which frames Williamson and Lewis as figures born into slavery who helped win the first Derby—an image that unsettles the genteel veneer Derby culture often projects.

Williamson’s rise was possible because the racetrack, unlike many other public institutions of the time, could be pragmatic about talent when money was at stake. Owners wanted winners. Trainers who could deliver winners held leverage, even in a society committed to racial hierarchy. But that leverage was always contingent. It existed inside white-controlled networks of capital and power. It could be revoked.

That contingency is part of why the inaugural Derby matters. It shows, in unusually clear relief, what Reconstruction sometimes allowed: moments when Black expertise could be publicly indispensable. It also hints at what would follow as the nation retreated from Reconstruction, and as segregation hardened into policy and custom.

The golden age that followed—and the mechanism of disappearance

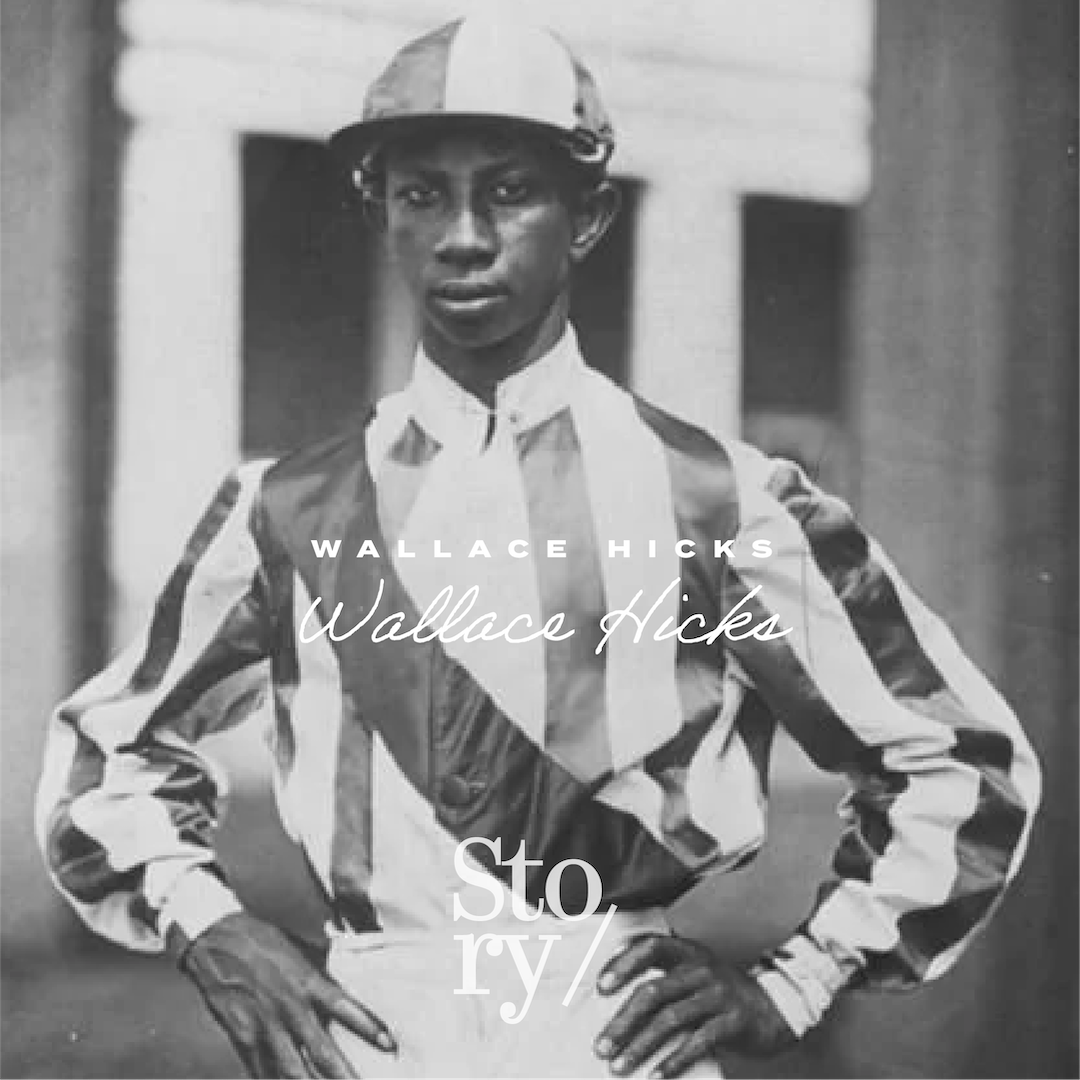

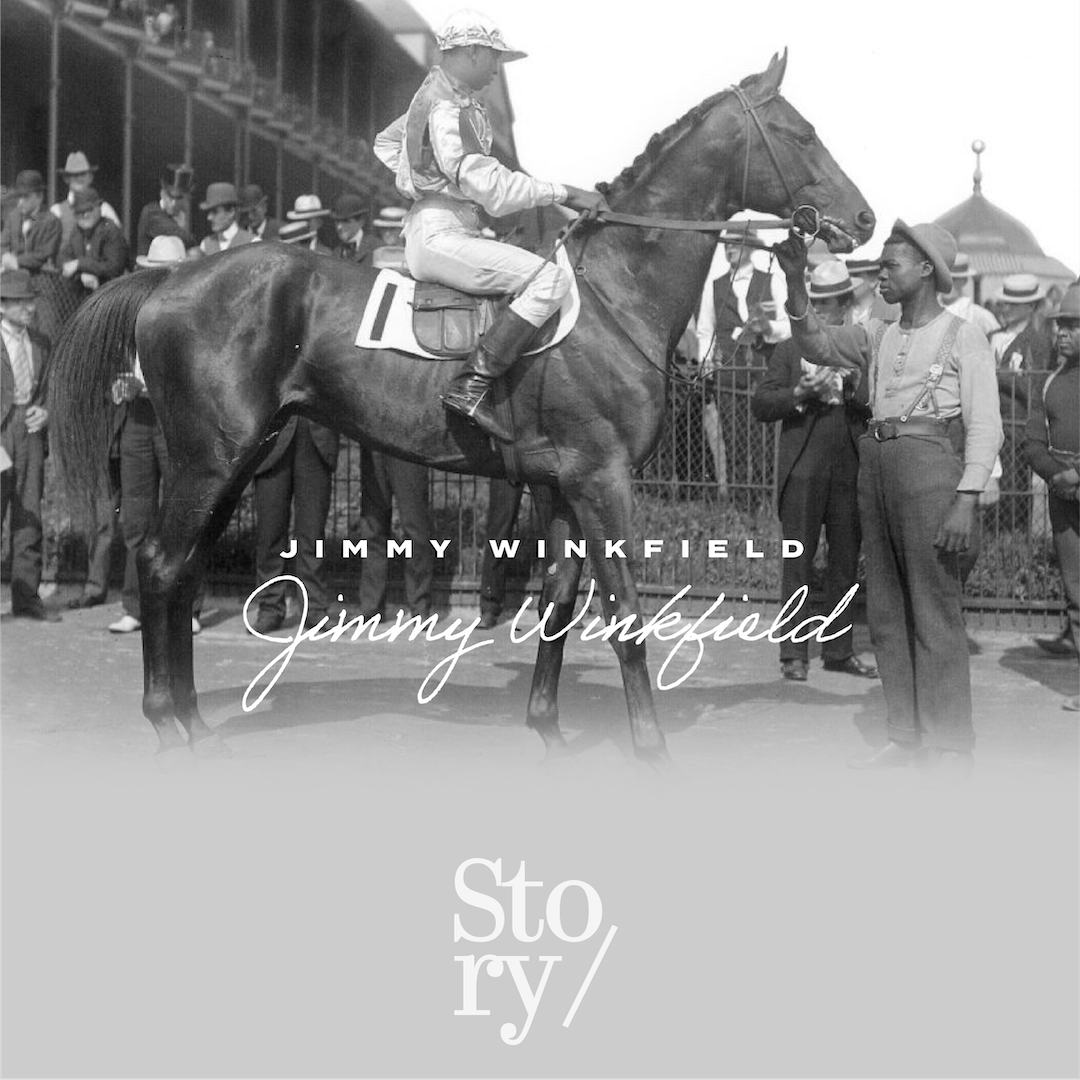

The inaugural Derby did not stand alone. In the late 19th century, Black jockeys won at an astonishing clip. Multiple sources note that African American riders won 15 of the first 28 Kentucky Derbies. Their names are not all household words now, but they were celebrities then, and their achievements shaped the sport’s tactics and style.

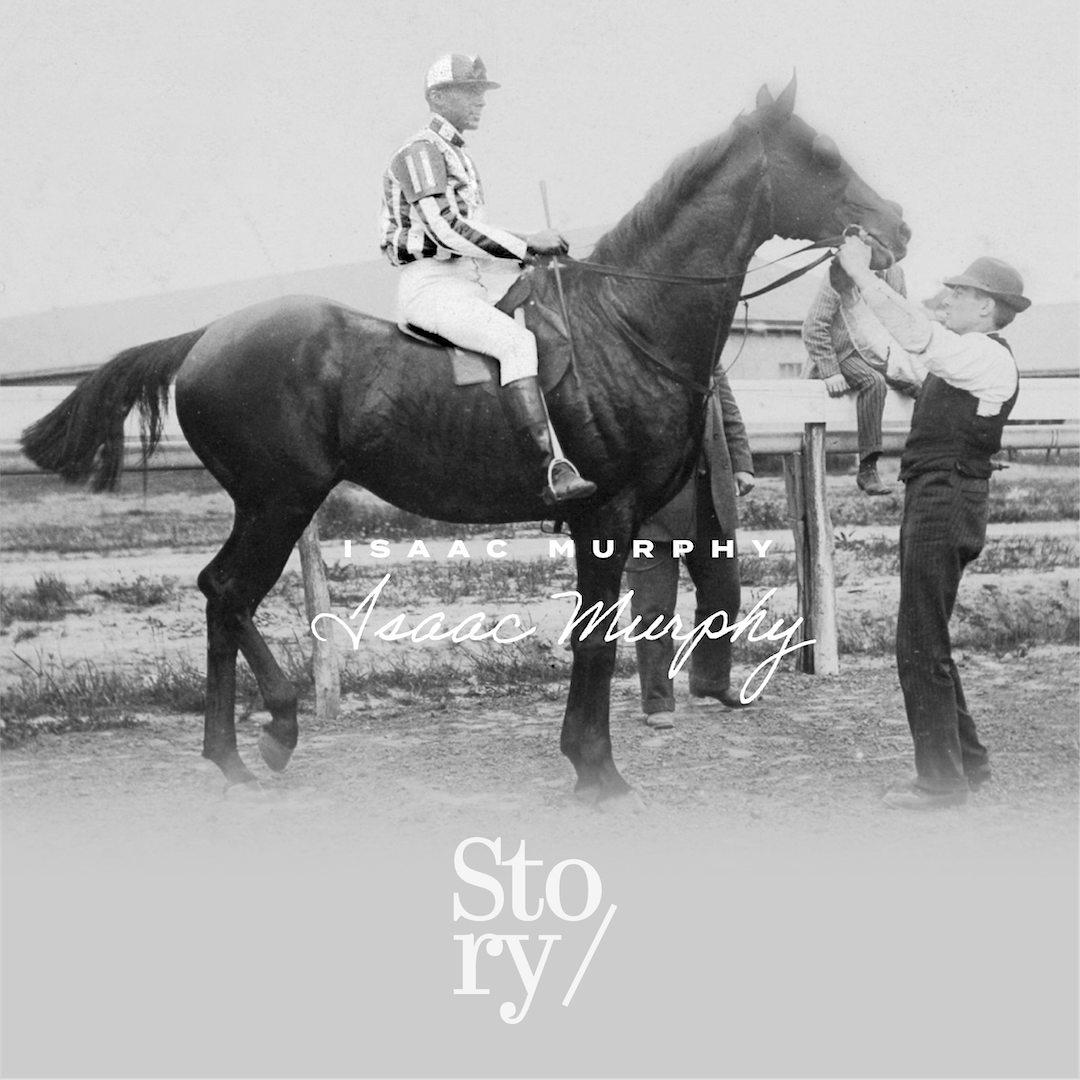

This is where Isaac Burns Murphy enters the broader narrative: a Black jockey who became one of the era’s most famous riders and a symbol of what Black stardom could look like in an America still determined to keep Black people “in their place.” Time magazine’s historical reporting describes Murphy as among the greatest jockeys ever, emphasizing both his brilliance and the sabotage and racial hostility that eventually hemmed in Black riders. The Washington Post has also explored Murphy’s life as a window into the possibilities and limits of Black heroism during and after Reconstruction.

Why, then, did the sport change? The simplest answer—racism—is true but incomplete. The better answer is that racism became organized, enforced, and economically rationalized through institutions once the sport’s financial stakes grew and once white riders and white power brokers decided jockeying was no longer “unsuitable” work.

Economic historians have tried to quantify this transformation. NBER research describes how Black jockeys were forced out of premier racing in the late 19th and early 20th centuries, situating the process within the broader rise of Jim Crow and the tightening of segregationist norms. The same body of work underscores that the inaugural Derby’s racial composition was a legacy of slavery-era labor patterns—and that the “regime change,” as the researchers frame it, became brutally apparent over subsequent decades.

Journalism has documented the mechanisms in more vivid terms: intimidation, violence, licensing barriers, and coordinated exclusion. Smithsonian Magazine recounts how, by the early 20th century, African American jockeys had largely disappeared from the Derby, despite their earlier dominance. The Guardian, writing about the “rise and fall of the black jockey,” points to the sharp contrast between 1875’s predominantly Black field and the near absence of Black riders in modern runnings.

These mechanisms were not unique to racing. They echo what happened across American society after Reconstruction: Black political power suppressed, Black economic advancement constrained, Black public presence policed. The racetrack is simply an unusually crisp case study because the scoreboard—wins, purses, trophies—made the contradiction undeniable. Black riders were not being pushed out because they were inferior. They were being pushed out because they were too successful, too visible, and too threatening to a racial order that demanded white supremacy, even in a game.

When you zoom back to the inaugural Derby, the statistic—thirteen of fifteen—begins to feel less like trivia and more like an index of what was taken. Not just jobs, but a birthright of expertise. Not just wages, but the right to be remembered as foundational.

The Derby as cultural theater—and why the origin story gets sanitized

The Kentucky Derby has always been more than a race. Clark’s model, borrowed from European events, aimed to fuse sport with spectacle. Even the later emergence of the Derby’s fashion culture reflects this impulse: to position the day as society, not just gambling; as tradition, not just commerce.

That framing has consequences. A high-society narrative often requires selective memory. It is easier to market an event as refined if its origins can be presented as quaint rather than complicated—if you can talk about hats and juleps without dwelling on the enslaved labor systems that produced the expertise that made the sport successful.

The erasure of Black jockeys fits neatly into that marketing logic. The story of thirteen Black riders at the starting line in 1875 interrupts the illusion that the Derby’s traditions are simply charming Americana. It forces a reckoning with where American “tradition” comes from: whose labor, whose risk, whose artistry, whose bodies.

That is why so many contemporary accounts of Black jockey history arrive with a tone of rediscovery—“forgotten,” “little known,” “overlooked.” Smithsonian literally calls them “forgotten jockeys.” The problem is not that the story was never told. The problem is that the institutions that control mainstream memory did not keep telling it, and in some cases may have preferred that it fade.

What it means to tell the 1875 story now

In recent years, there have been renewed efforts to foreground Black horsemen in Derby history. The Kentucky Historical Society has published accessible public history explaining the early presence of Black jockeys and the barriers that later excluded them. The racing world itself has made gestures toward recognition: exhibits, commemorations, corporate-sponsored initiatives that highlight Black Derby winners, and new awards named for Ansel Williamson.

There is a temptation to read these gestures as simple progress—belated but genuine. Some of it is. But a seasoned look requires noticing how memory work can also function as reputation management. A sport wrestling with modern critiques about equity, access, and representation may find it useful to celebrate a “diverse past,” especially if that celebration does not demand structural change in the present.

The inaugural Derby provides a way to hold both truths at once. It allows us to honor Oliver Lewis and the other Black riders not as symbolic figures but as working professionals whose skill shaped American sport at its inception. It also forces us to ask why their dominance did not translate into a durable, protected place in racing’s power structure. The answer, again, is not mysterious: power was never evenly distributed. Talent alone was not enough.

The question that remains, 150 years later, is what a truthful retelling demands. It demands precision about the facts: the date, the distance, the purse, the crowd, the people, the time. It demands honesty about the context: slavery’s legacy in horse culture, Reconstruction’s fragile openings, Jim Crow’s closing fist. And it demands care with what the record can’t fully provide—names and lives that remain only partially documented, not because they were unimportant, but because the nation that watched them win did not build archives as lovingly for Black champions as it did for white owners and institutions.

If you tell the inaugural Derby story straight, the line you end up writing is not only about Aristides. It’s about an America that once watched a predominantly Black field thunder down a Louisville stretch and accepted it as normal—until “normal” changed.

In 1875, the Derby’s starting gate offered a fleeting picture of what American sport could look like when skill was allowed to outrun the color line. The tragedy is not that the picture was blurry. The tragedy is that, for so long, it was tucked away.

More great stories

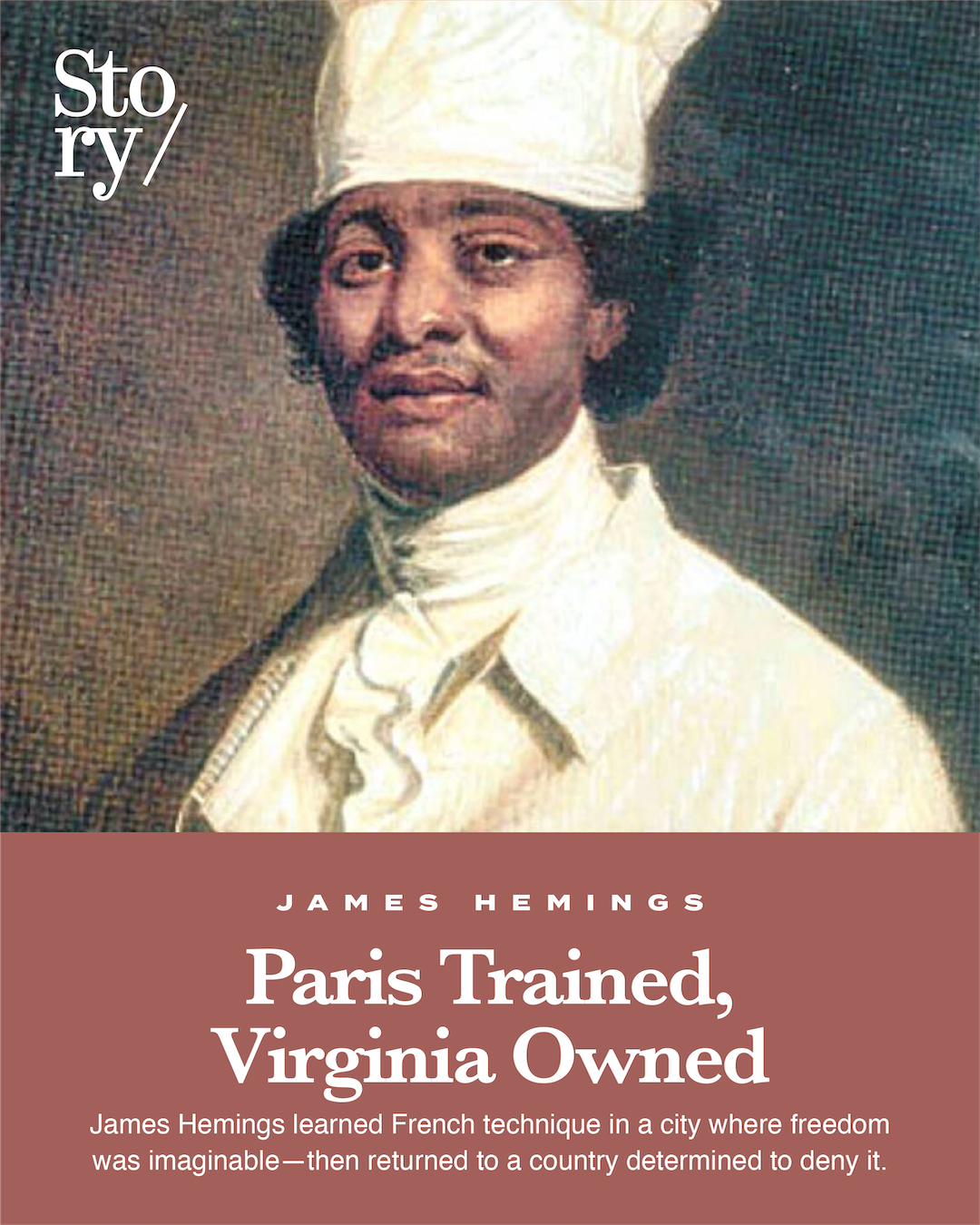

James Heming: Paris Trained, Virginia Owned