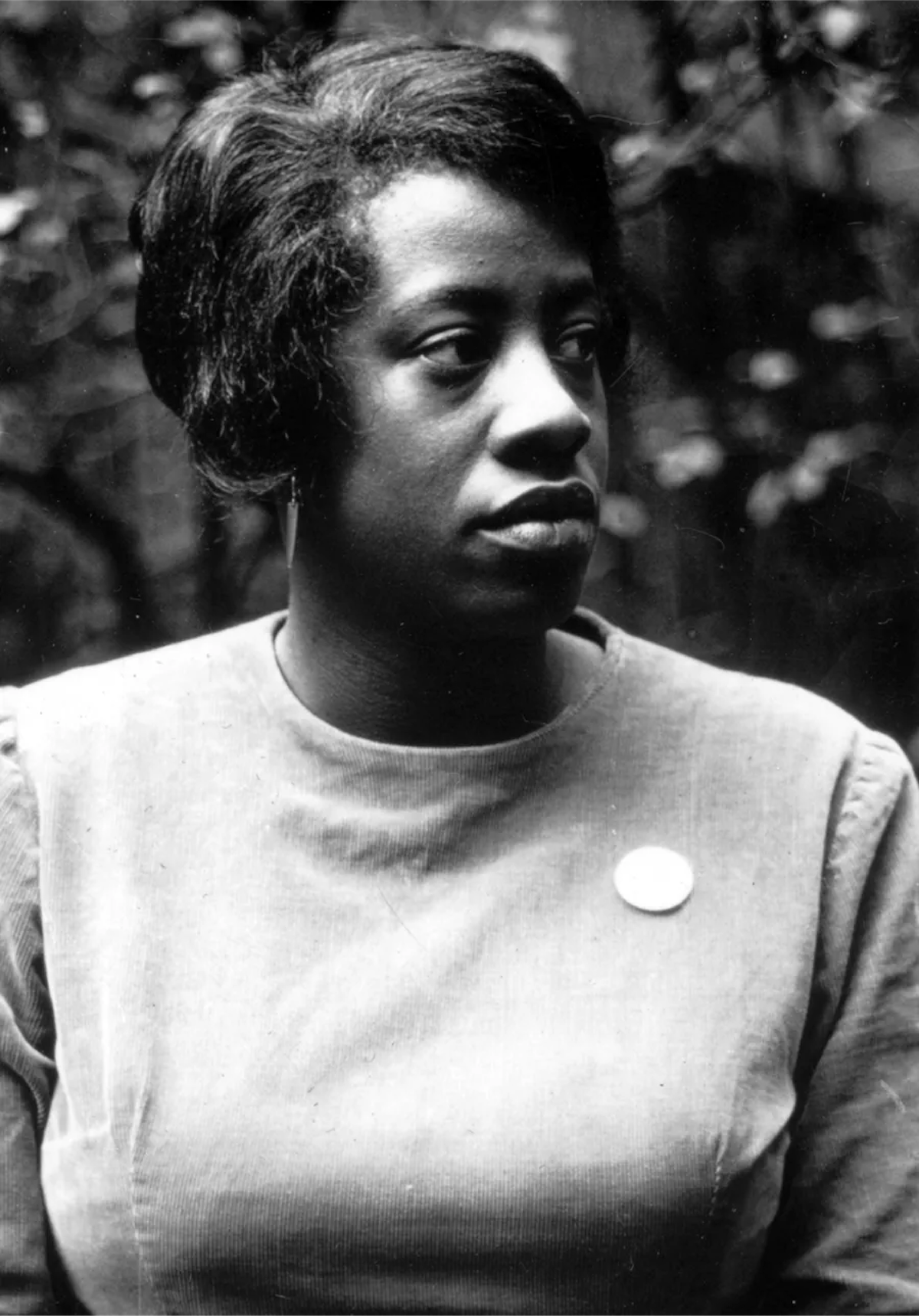

Unita Blackwell’s genius was not a mystical trait. It was a disciplined refusal to accept the limits set around her life. She was born into a Mississippi that treated Black people as labor without citizenship. She helped break that system’s hold on the ballot. Then, when the nation congratulated itself for change, she kept insisting on the unfinished work: the water, the streets, the housing, the basic infrastructure that makes a life something other than survival.

Unita Blackwell’s genius was not a mystical trait. It was a disciplined refusal to accept the limits set around her life. She was born into a Mississippi that treated Black people as labor without citizenship. She helped break that system’s hold on the ballot. Then, when the nation congratulated itself for change, she kept insisting on the unfinished work: the water, the streets, the housing, the basic infrastructure that makes a life something other than survival.

By KOLUMN Magazine

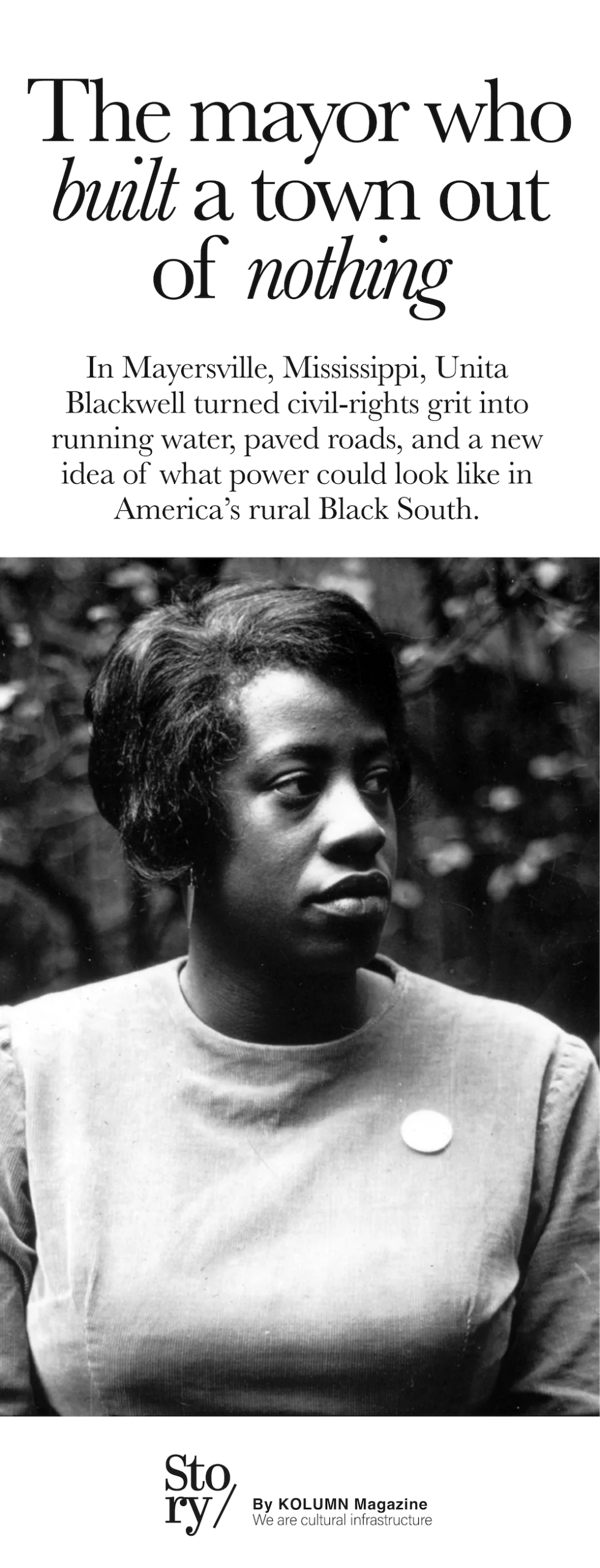

When Unita Blackwell took office as mayor of Mayersville, Mississippi, in 1976, the setting looked less like the post–civil rights era than a holdover from the sharecropping economy that had long defined the Delta. Many residents lived in tin-roofed shacks without running water. Streets were unpaved. A sewer system didn’t exist. The town’s smallness—roughly 500 people in some accounts—was matched by its invisibility: Mayersville was the kind of place America drove past, if it noticed it at all.

Blackwell understood that invisibility as both a political condition and an administrative problem. The civil rights movement taught her that power could be denied through violence and law, but also through neglect—through the slow, grinding absence of the basics. In Mayersville, the same country that could pass landmark legislation still allowed communities to go without public water, paved roads, or adequate housing. Blackwell’s mayoralty would become an argument—made not in rhetoric alone, but in grant applications, planning meetings, and incremental construction—that democracy had to be physical. It had to show up in pipes and streetlights, in fire protection and public housing, in whether a grandmother could turn a faucet and trust what came out.

This is part of why Blackwell’s significance doesn’t sit neatly in a single box labeled “civil rights leader” or “first Black woman mayor.” She was both. And she was something else, too: a translator between two eras of American struggle. She carried the movement’s language of rights into the stubbornly practical world of municipal governance, insisting that the promise of the ballot had to be paired with the promise of livable community.

The Delta that made her—and tried to break her

Unita Zelma Blackwell was born in 1933 in Lula, Mississippi, and raised in the Delta’s harsh logic of plantation labor and racial hierarchy. The Mississippi Encyclopedia’s account of her life emphasizes how early she entered the world of work and how thoroughly the “plantation” governed daily life—down to whether children went to school or the fields. The Delta was not simply poor; it was organized to keep Black families economically precarious and politically powerless.

If that sounds like background, it’s because America has learned to treat the rural South as background. Blackwell’s life makes that habit harder to defend. She came of age in a system where the lines between public and private coercion blurred: landowners, employers, and local officials could function as a single apparatus. Voting—where it existed in theory—was fenced off through tests, intimidation, and the knowledge that trying could cost you your job, your home, your safety.

In interviews and oral histories, Blackwell returned to the emotional texture of that world: the constant calibration required to survive around white power, the caution that seeped into Black life as second nature, the sense that rules could change at any moment and would never be changed for you. Her later insistence that people learn “how to move” no matter what was against them came out of that childhood training in constraint—then flipped into a philosophy of action.

Freedom Summer didn’t arrive like a rescue. It arrived like a spark.

Blackwell’s political awakening is often dated to 1964, when civil rights workers came through Issaquena County during Freedom Summer, meeting in churches and speaking directly about the right to vote. In the SNCC Digital Gateway’s profile, Issaquena is described as a place where no Black person was registered to vote—an index of how absolute the exclusion was. That detail matters because it helps explain why “registering voters” in Mississippi was not a polite civic project; it was an assault on a local regime.

Blackwell went with others to the courthouse to attempt registration, facing the familiar weaponry of Mississippi’s white resistance. The story turns quickly from civic instruction to punishment: she and her husband lost their jobs after participating in registration efforts, a pattern that activists across the state described—economic retaliation as a key enforcement mechanism. In other words, the movement was not simply asking people to vote; it was asking them to risk survival.

Blackwell took that risk, and she stayed. Over time she became a project director and field secretary for the Student Nonviolent Coordinating Committee (SNCC), helping organize voter drives and political education across Mississippi. Her work put her in the movement’s engine room, where strategy depended on local knowledge—who could be trusted, which roads were safe, which sheriffs were especially eager to arrest someone, which families might feed volunteers even when it endangered them.

Her significance here is also methodological: Blackwell represents the reality that the movement’s most consequential work was often done by people whose names weren’t going to become national shorthand. SNCC’s organizing model relied on local leaders who could endure a level of pressure outsiders couldn’t. The result was a movement that was “national” only because it was intensely local, multiplied across counties like Issaquena.

Atlantic City and the limits of American liberalism

Blackwell’s story intersects with one of the era’s most revealing confrontations: the Mississippi Freedom Democratic Party (MFDP) challenge at the 1964 Democratic National Convention in Atlantic City. She traveled as part of the MFDP delegation seeking to unseat Mississippi’s all-white “regular” delegation and force the Democratic Party to confront what it tolerated in the name of coalition politics.

The MFDP challenge is often remembered through the searing moral clarity of testimony—most famously from Fannie Lou Hamer—but its larger meaning is that it exposed the friction between civil rights demands and the party system’s instinct for containment. Blackwell, in interviews conducted for Eyes on the Prize, spoke directly about her role and the atmosphere around SNCC and the MFDP—how ordinary Mississippians found themselves pushed into extraordinary visibility, and how the machinery of national politics responded.

In retrospect, the MFDP fight reads like a dress rehearsal for later debates about representation: Who counts as the legitimate voice of a constituency? What happens when institutional processes are designed to recognize power, not justice? When the MFDP was offered a compromise that fell short of seating its delegation fully, many activists interpreted it as proof that moral arguments alone could not defeat entrenched political calculation.

For Blackwell, this wasn’t a reason to leave politics; it was evidence that politics had to be widened. If a national party could be forced to look at Mississippi—and still choose half measures—then local power mattered even more. It was not enough to shame the system. You had to build an alternative inside your own county, then inside your own town.

A lawsuit about school pins—and a lesson about strategy

The civil rights movement is sometimes narrated as marches and speeches, but its day-to-day reality included school boards, court filings, and the tight focus on a single local injustice that could expose the whole structure.

Mississippi Today recounts that in 1965 Blackwell became involved in litigation challenging the suspension of hundreds of students, including her son, for wearing SNCC “Freedom” pins—part of a broader struggle over speech, discipline, and desegregation. The case’s significance is not only legal. It shows the movement’s tactical breadth: a mother fighting a school punishment could be participating in the same democratic project as a delegate in Atlantic City.

This is the connective tissue that later made Blackwell an unusual mayor. She did not treat governance as separate from struggle. She treated it as another front. The same instincts—identify the mechanism of exclusion, confront it directly, build a coalition, force an institution to answer—apply whether the institution is a courthouse denying voter registration or a bureaucracy withholding infrastructure.

From movement to municipal power

In 1976, Blackwell was elected mayor of Mayersville, making her the first Black woman elected mayor in Mississippi. That “first” matters, but it can also flatten the story into symbol. The deeper point is what she did with the office.

The Washington Post obituary describes how she pursued incorporation as a prerequisite for federal funding—an example of her pragmatic understanding that dignity often requires paperwork. “You can’t get federal dollars for housing if you’re not an incorporated town,” she explained in later years, capturing the unromantic reality of rural development: communities are punished not only by discrimination but by administrative invisibility.

Once in office, Blackwell spearheaded the establishment of public water and sewer systems, oversaw the paving and naming of roads, and helped secure basic municipal services, including fire protection. The National Park Service biography highlights her ability to obtain federal grant money for infrastructure and public safety—police and fire departments, paved streets, housing for the elderly and disabled, and other improvements that changed what daily life could look like in Mayersville.

This work is easy to underestimate because it lacks the cinematic clarity of a march. But the politics of infrastructure is a politics of whose life is considered worth investment. For a town that had been functionally abandoned, pipes and pavement were not mere amenities—they were evidence that citizenship had material meaning.

The “genius grant” and the politics of rural visibility

In 1992, Blackwell received a MacArthur Fellowship—often called the “genius grant”—that brought national attention not just to her but to Mayersville and the ongoing conditions of rural poverty. The award was frequently framed as recognition of her imaginative approach to community development: securing housing, leveraging federal funds, and translating national programs into local benefits.

The MacArthur Foundation’s profile describes her as a leader who fought to incorporate Mayersville and raise money for water, sewerage, and housing—and it notes her leadership at the national level, including serving as president of the National Conference of Black Mayors. In other words, the fellowship wasn’t only a personal honor; it validated a style of leadership that mainstream America had not typically celebrated: the rural Black municipal leader as policy innovator.

What the MacArthur Fellowship also did was reverse the direction of attention. For decades, the movement had been about forcing the nation to look at Mississippi’s cruelty. Blackwell’s mayoral work forced the nation to look at Mississippi’s neglect—and at the creativity required to survive it.

“People think we’re backwards”: Defending rural life without romanticizing it

Blackwell resisted caricature in both directions. She rejected the condescension that treated rural communities as stuck in time. But she also resisted romantic narratives that made poverty look like authenticity.

In a Washington Post interview quoted in her obituary, Blackwell pushed back against urban assumptions: rural residents might not have “push-buttons,” she said, but those who live with the land can have a “real feeling for life.” Read carefully, this isn’t nostalgia—it’s a demand to be understood on one’s own terms, not through the lens of deprivation.

At the same time, her mayoral agenda was an indictment of the idea that rural life must be synonymous with scarcity. She didn’t defend Mayersville by arguing that it didn’t need infrastructure. She defended it by insisting the town deserved infrastructure without having to surrender its identity.

This is a critical part of her historical significance: she modeled a politics of rural Black self-determination that did not depend on escape. In American mythology, progress often means leaving. Blackwell’s progress meant staying—and changing the terms of what staying could mean.

Leadership beyond Mayersville: Networks of Black municipal power

Blackwell’s influence expanded beyond her town. The National Park Service notes that she was elected chair of the National Conference of Black Mayors in 1989 and served as president from 1990 to 1992. The MacArthur Foundation similarly emphasizes her national leadership and describes her as the first woman to hold that presidency.

These details matter because they show how Blackwell’s work fit into a broader ecosystem of Black governance that emerged after the movement’s legislative victories. In many cities, Black political power rose through mayoral offices and city councils; in rural America, that pathway existed too, but with fewer resources and less media attention.

The National Conference of Black Mayors functioned as a platform for sharing strategies and elevating municipal concerns—housing, economic development, infrastructure—often in communities that were simultaneously underfunded and overpoliced. Blackwell’s presence in that world signals that her genius was not only local; it was organizational. She understood that Mayersville’s fate was linked to policy decisions made far away, and that small-town leaders needed collective leverage to be heard.

A global dimension: China, diplomacy, and an expansive definition of citizenship

One of the more surprising threads in Blackwell’s biography is her involvement in U.S.–China cultural exchange and international travel. The MacArthur Foundation notes her activity with the U.S./China People’s Friendship Association, reflecting a public life that stretched well beyond the Delta.

It’s tempting to treat this as an eccentric footnote—“the Delta mayor who traveled abroad”—but it can also be read as part of her political philosophy. Blackwell’s life suggests a refusal to accept the boundaries assigned to her. The same system that tried to keep her from voting would have happily kept her from seeing the world. International travel, in this sense, becomes another form of citizenship: an insistence that rural Black leadership belongs in global conversations, not as charity cases but as participants.

This broadened frame also complicates the stereotype of rural politics as parochial. Blackwell’s ruralness didn’t mean narrowness; it meant she carried local knowledge into larger arenas, often reminding national and international audiences that poverty and power are not abstractions—they have addresses.

Memory, preservation, and the fight over what counts as history

In the years after Blackwell’s death in 2019, the question of how to preserve her legacy has taken on literal form. The National Trust for Historic Preservation has written about efforts to protect and interpret the Unita Blackwell Freedom House, framing it as a site where the movement’s local architecture—homes, meeting places, everyday spaces—can be honored as historically significant.

Preservation matters here because Blackwell’s story risks being flattened into a plaque and a first. The work of saving a structure linked to her life becomes a broader argument: that civil rights history is not only found in famous bridges and national monuments, but in rural homes where organizers lived, planned, and endured retaliation.

This is also a reminder that the struggle continues in the realm of narrative. What gets preserved gets taught. What gets taught shapes what future leaders imagine is possible.

What Unita Blackwell’s life tells us about power now

Blackwell’s life sits at the intersection of three enduring American questions.

The first is about democracy. Her organizing underscores that the right to vote is not self-executing; it requires protection, access, and a willingness to confront the local mechanisms of suppression. Her participation in the MFDP challenge underscores that even when marginalized citizens follow the rules, institutions can still deny them legitimacy.

The second is about political economy. Her mayoral record suggests that civil rights victories without material investment can leave communities in a new form of abandonment. The story of Mayersville—water systems, sewer lines, paved roads—makes the case that governance is not just representation; it is capacity.

The third is about scale. National narratives of progress often overlook the granular work of local officials, especially in rural places. Blackwell forces a recalibration: she demonstrates that some of the most consequential fights for equality occur in spaces where the cameras rarely stay. A small town can be a testing ground for whether democracy is real, and a mayor can be a civil rights figure not because she speaks in national arenas, but because she makes a town livable.

Her story also challenges a common misunderstanding of “post–civil rights” America. The movement didn’t end; it changed venues. In Blackwell’s life, the courthouse steps of voter registration become the city hall desk of grant writing. The confrontation with the sheriff becomes the negotiation with federal agencies. The moral drama becomes administrative persistence. None of it is less political. It is simply less celebrated.

The long arc is made of short distances

Unita Blackwell’s genius—if we use that word the way MacArthur did—was not a mystical trait. It was a disciplined refusal to accept the limits set around her life. She was born into a Mississippi that treated Black people as labor without citizenship. She helped break that system’s hold on the ballot. Then, when the nation congratulated itself for change, she kept insisting on the unfinished work: the water, the streets, the housing, the basic infrastructure that makes a life something other than survival.

In the popular memory of the civil rights movement, history moves through grand moments: a convention challenge, a televised testimony, a landmark statute. Blackwell’s story insists on another tempo. History also moves through the painstaking accumulation of small wins, through the insistence that a forgotten hamlet deserves the same public goods as any suburb. It moves through people who learn how to move, no matter what is against them—and then teach others how to do the same.

Mayersville is still small. The Delta still carries the weight of structural inequality. But the map of what was possible changed because Unita Blackwell decided that politics could be both a fight for rights and a plan for plumbing—and that dignity was not complete until it reached the ground.

More great stories

Ida B. Wells: The Case Against American Innocence