Bearden moved through multiple idioms and multiple worlds: formal study and self-teaching, illustration and fine art, social realism and abstraction, studio solitude and civic cultural politics.

Bearden moved through multiple idioms and multiple worlds: formal study and self-teaching, illustration and fine art, social realism and abstraction, studio solitude and civic cultural politics.

By KOLUMN Magazine

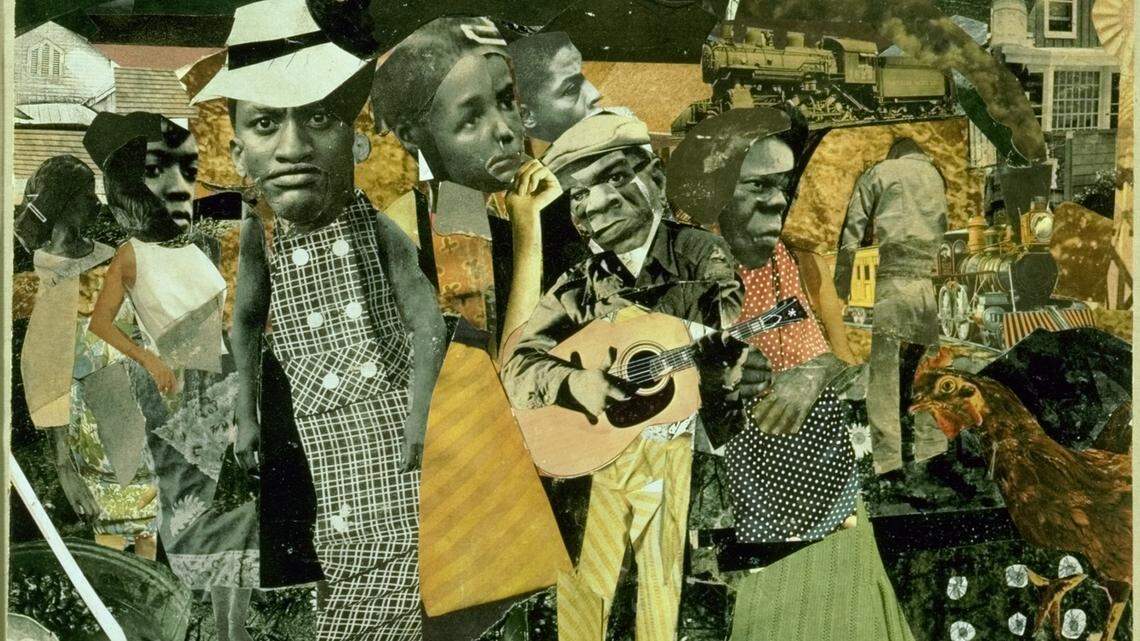

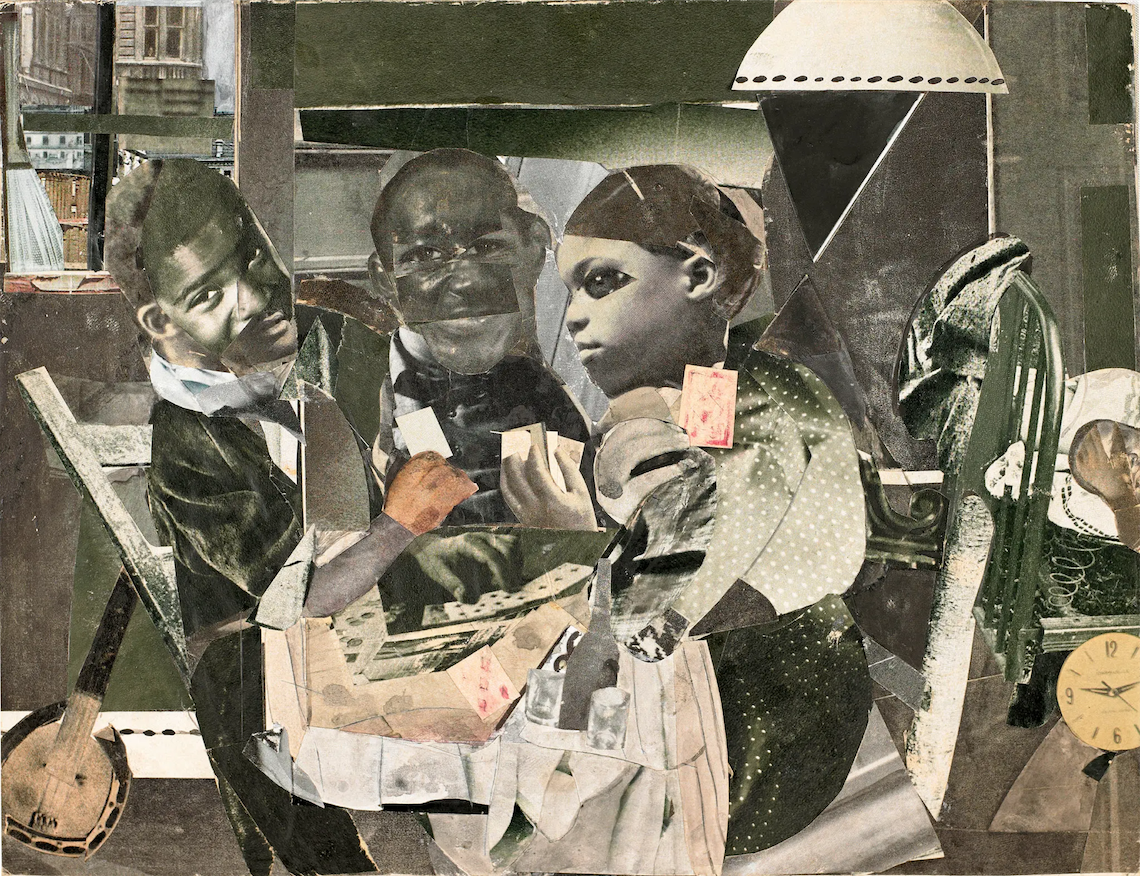

Romare Bearden’s art does not ask to be looked at politely. It insists on being entered. The figures in his collages—women leaning into a kitchen conversation, men gathered in a doorway as if a horn section is about to count off, a child’s face peeking out from a cut-paper window—feel less like characters arranged for our viewing than neighbors caught mid-sentence. The trick, and the power, is that Bearden built these lives out of fragments: magazine clippings, painted papers, printed textures, photographic eyes and hands, slices of patterned cloth turned into architecture. He made pictures the way memory works, the way history survives, the way Black life in America has so often had to be reconstructed from what was torn away.

That reconstructive force—part aesthetic, part politics, part personal archive—explains why Bearden remains a central figure in American art and why each return to his work feels less like revisiting a “style” than re-entering a method of seeing. In the second half of the twentieth century, when abstraction’s cool authority and Pop’s commercial glare could flatten human particularity, Bearden devised a language that kept the lived world intact. He took the modernist logic of collage—its leaps, its ruptures, its refusal of seamless illusion—and transformed it into a narrative engine capable of carrying ancestry, migration, church ritual, street music, and domestic intimacy all at once. In doing so, he offered not only a new formal vocabulary but a corrective: a visual record that made Black interior life, Black neighborhoods, Black mythmaking, and Black modernity impossible to dismiss as peripheral.

He was, as contemporaries in mainstream press would later describe him, a “preeminent” painter and collagist whose work fashioned stories about the dignity of Black people and the textures of Southern living, even when those stories were being ignored or caricatured elsewhere. But the story of Bearden’s significance is bigger than the familiar arc of genius recognized late and canonized after death. It is a story about how one artist threaded together three Americas that often pretended not to know one another: the rural South of ancestral memory, the urban North of the Great Migration and Harlem’s crowded vitality, and the art-world America where Black artists were routinely asked to explain themselves rather than simply be taken seriously.

Bearden understood early that the stakes were not just personal. They were infrastructural. Who gets to be seen? Who gets to be collected, taught, exhibited, written into the record? Who gets to experiment without being told their work must represent an entire race? These questions run beneath his pictures, and they run beneath his organizing work as well—most notably in the late 1960s, when he helped co-found Cinque Gallery as a platform for artists of color shut out of mainstream spaces. To look carefully at Bearden is to watch an artist refuse the false choice between art and advocacy. He practiced both, and he did it with a feel for rhythm that critics have long associated with jazz: improvisation within structure, variation on a theme, the surprise of a cut that becomes a chord change.

If Bearden’s work feels inevitable now—if it is easy to forget that collage once sat awkwardly in the hierarchy of “serious” painting—his own path to that language was anything but linear. He moved through multiple idioms and multiple worlds: formal study and self-teaching, illustration and fine art, social realism and abstraction, studio solitude and civic cultural politics. Like many Black artists of his generation, he did not inherit an art system designed to receive him. He had to make his own.

He was born in 1911, a date that places him at a hinge in Black American life: post-Reconstruction backlash had hardened into Jim Crow; the Great Migration was beginning to gather force; the cultural ferment that would become the Harlem Renaissance was still a few years away. By the time Bearden came into artistic maturity, Harlem was no longer a single “movement” but an ecosystem—clubs and churches, newspapers and rent parties, political meetings and salon conversations—that shaped how Black culture would speak to itself and to the nation. Bearden’s later collages, so often read as nostalgic or lyrical, can also be read as documents of this ecosystem’s durability: not a postcard version of Harlem, but a working model of Black social life as an engine of survival.

One reason the work carries that density is that Bearden approached collage not as decoration but as an epistemology: a way of knowing. In the collage, there is no single authoritative viewpoint; there are multiple sources, multiple scales, a visible record of construction. When you can see the seams, you can see the labor. That matters in a country where Black experience has so often been made invisible, flattened, or appropriated. Bearden did not offer invisibility. He offered assembly.

In the 1960s, that assembly became the defining gesture of his career. Critics and scholars have often described the “Projections” era—Bearden’s breakthrough with photomontage and collage—as a moment when he chose a medium that could hold both the ready-made and the imagined, allowing him to reconstruct the world rather than simply depict it. The timing was not incidental. The decade’s political turbulence—civil rights, Black Power, the urban crises and cultural awakenings of the period—forced American institutions to confront questions they had long dodged. Museums, galleries, and critics were not exempt. Bearden’s collages met that turbulence with a form built for rupture and repair.

A useful way to understand his leap into collage is to see it alongside his earlier experiments. Bearden could paint, and paint well. He had made work in a social realist mode in the 1930s and 1940s, when artists across the country were grappling with poverty, labor, and the human consequences of economic collapse. Social realism offered directness: bodies, streets, workplaces rendered with legibility. But for Bearden, legibility was not enough. His subject—Black life—was legible to Black communities already, and often illegible to the white institutions that controlled cultural prestige. To simply “show” Black life within existing frames risked reinforcing those frames. Collage offered a more radical proposition: it could break the frame and rebuild it.

The scholar Lee Stephens Glazer, writing on Bearden’s “Projections,” describes how questions of art and race in his work are inseparable from the strategy of signification—the way Black cultural expression encodes meaning through layering, reference, and transformation. That is, Bearden’s collage is not just a formal technique borrowed from European modernism; it is also a visual cousin to practices embedded in Black culture—call-and-response, sampling, quilting, improvisation, and the remixing of inherited forms to speak present truths. This is one reason Bearden’s work does not feel like an imitation of Cubist collage or Dada photomontage, even when it shares their DNA. His collages are not primarily about shock or anti-art provocation. They are about the dignity of the everyday and the insistence that Black life contains multitudes: myth and mundanity, pain and celebration, private interiority and public performance.

Bearden himself leaned into the musical analogy. Galleries and institutions that have documented his practice note that he understood his process as akin to jazz and blues composition, beginning with a fragment and allowing the work to evolve spontaneously, the way a musician might build a solo from a motif. You can feel that improvisation in the way a face might be built from mismatched photographic parts—an eye that belongs to one person and a mouth that belongs to another—yet still resolves into a coherent emotional presence. The “wrongness” becomes right, because the picture is not claiming to be a single moment photographed. It is claiming to be a life remembered, a community assembled, a history made visible.

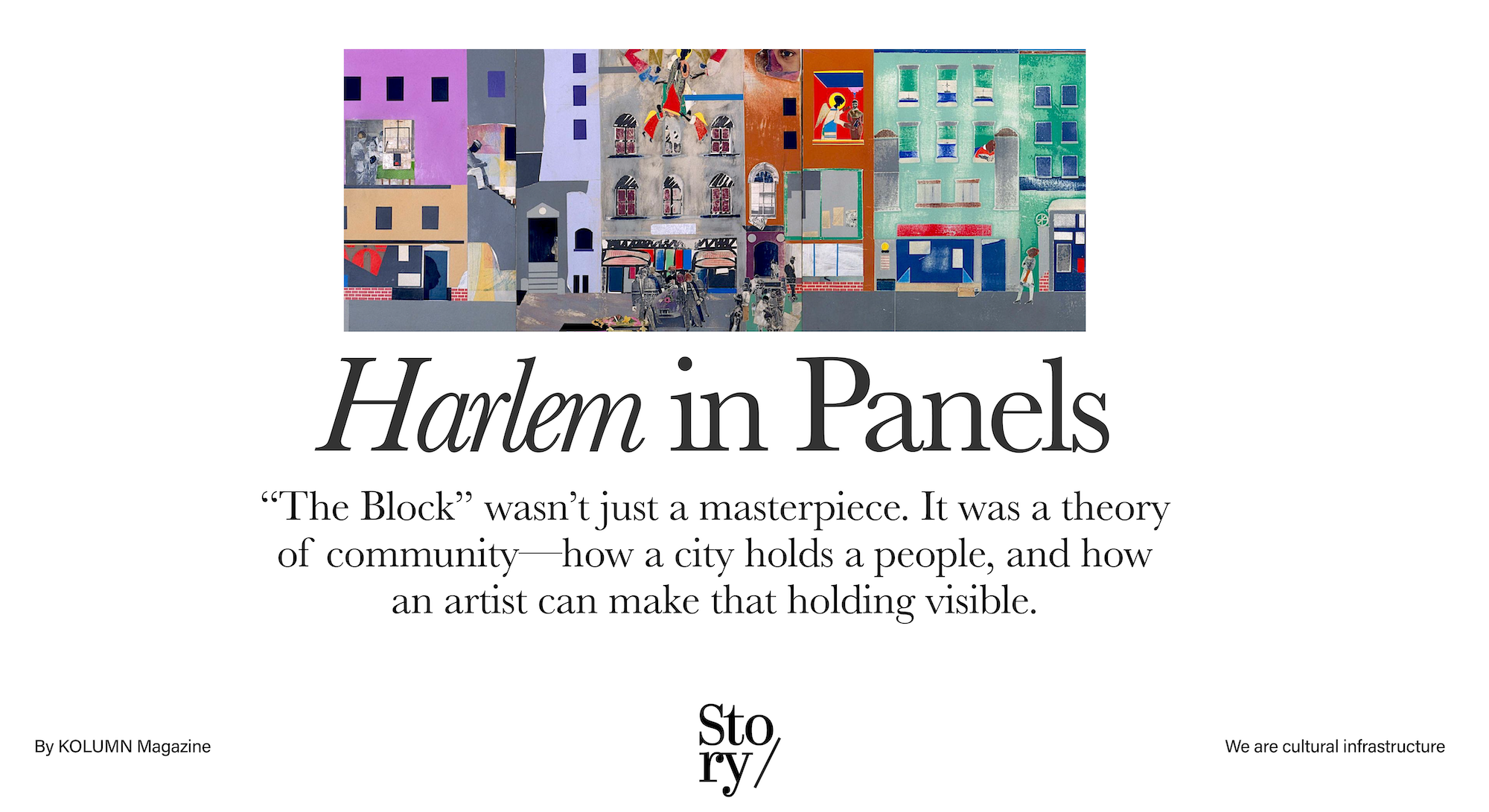

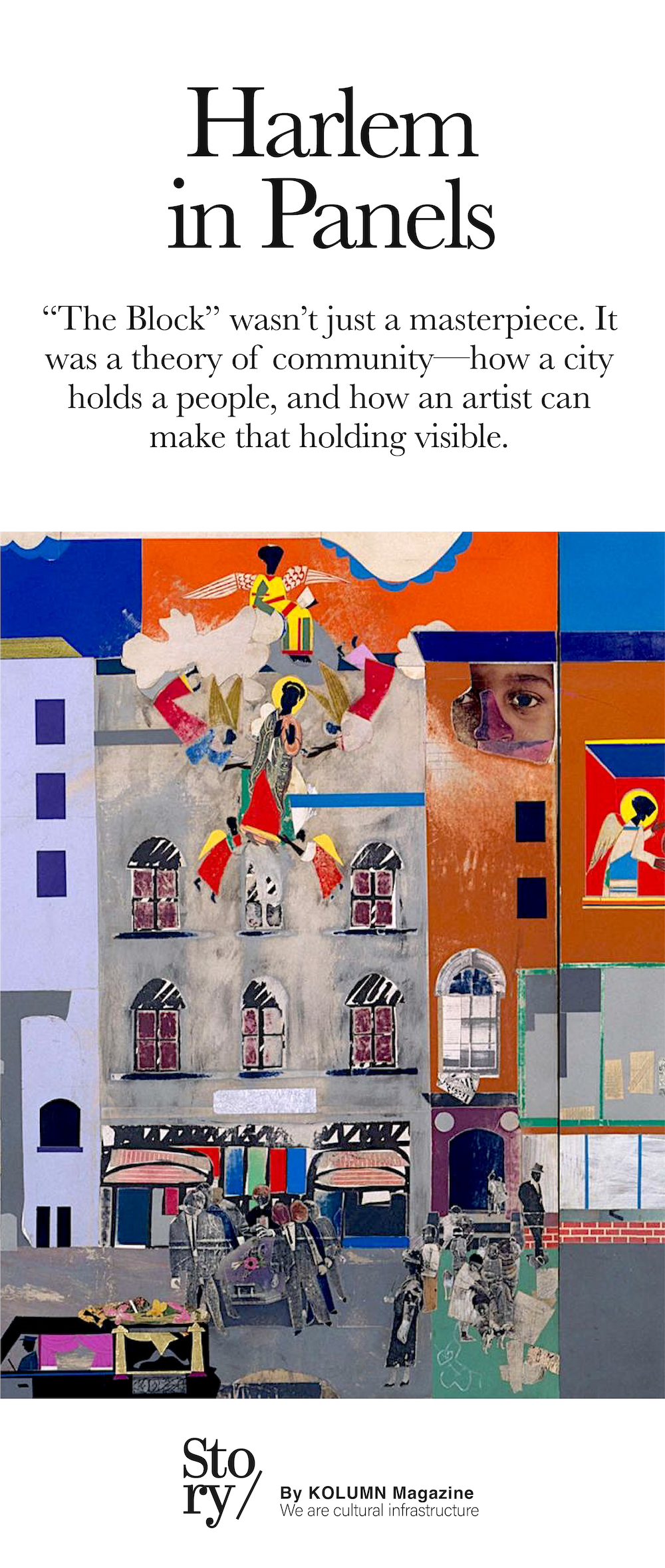

If you want to see this method at an epic scale, you go to “The Block.” Created in the 1970s, it stretches across multiple panels like a neighborhood seen in fragments, storefronts and stoops stacked into an urban hymn. The Metropolitan Museum of Art presents it not simply as a major work but as a bridge between art history and lived city life, a modernist mural that treats a Harlem streetscape as worthy of the panoramic tradition once reserved for pastoral Europe or heroic battle scenes. In “The Block,” Bearden’s collage logic becomes architectural. The street is built out of cuts, but it holds. The effect is not disorientation but recognition—especially for viewers who have known neighborhoods where life happens in public view, where the sidewalk is a living room, where the corner store is a community bulletin board, where music spills out of windows and church outfits turn the street into a runway.

That recognition is not accidental. Bearden’s work is often discussed as “representing” Black life, but representation can be a trap word—suggesting that the work stands in for something else, that it is a translation for outsiders. Bearden’s pictures do more than represent. They participate. They behave like the life they depict: layered, communal, improvisational, sometimes loud, sometimes intimate. A Bearden collage can feel like overhearing a conversation you are not meant to interrupt.

This participatory quality is one reason his influence extends beyond visual art. In KOLUMN Magazine’s reflection on August Wilson, the playwright’s famous “four B’s” are invoked—blues, Borges, Baraka, and Bearden—with Bearden specifically credited as a model for collaging fragments of Black life into a coherent whole. (KOLUMN Magazine) That is a striking line because it maps Bearden’s visual strategy onto narrative drama: separate scenes, separate voices, separate historical pressures brought together into a structure that feels inevitable only after you have heard it. Wilson’s America is a collage of decades. Bearden’s Harlem is a collage of afternoons. The kinship is real, and it underscores a broader point: Bearden did not just make images; he offered a formal grammar that other storytellers could borrow.

To understand how he arrived at that grammar, it helps to trace his movement through institutions—some welcoming, many not—and his navigation of Black cultural politics. Bearden lived in a period when Black artists were often forced into false binaries: either make “universal” art (code for work that did not foreground Blackness) or make explicitly racial art that could be pigeonholed as sociological rather than aesthetic. Bearden refused the binary. His work is full of Black specificity—church rituals, Southern memory, Harlem nightlife—and also full of formal exploration that places him in conversation with modernist peers. That refusal required a kind of double competence: the ability to move through the art world’s formal debates while remaining accountable to the community contexts his work drew from.

His community commitments were not confined to the canvas. The late 1960s brought a crisis of legitimacy for major cultural institutions, especially around their treatment of Black artists. The Smithsonian’s Archives of American Art notes that Cinque Gallery, founded in 1969 by Bearden along with Ernest Crichlow and Norman Lewis, was created to exhibit both new and established African American artists and to provide community educational programs; it was named after Joseph Cinqué of the Amistad rebellion. ArtNet, looking back on Cinque’s origins, frames it as a response to a lack of exhibition opportunities—artists taking matters into their own hands and creating a nonprofit space in downtown Manhattan. In other words: Bearden didn’t simply critique exclusion. He helped build an alternative.

This matters for how we talk about Bearden’s “significance.” Too often, significance is narrated as institutional validation: a retrospective, a museum acquisition, a stamp, a foundation. Bearden has all of these—The Root noted in 2011 that the U.S. Postal Service honored him with a set of Forever stamps during his centennial year, alongside a swell of exhibitions. But Bearden’s deeper significance is that he understood the ecosystem required for Black art to thrive. He was not only an artist but an architect of cultural infrastructure—someone who saw that talent alone is not enough when the gates are controlled elsewhere. That insight aligns with the ethos that many Black-led platforms—including publications like yours—have been advancing: the necessity of credible storytellers and durable institutions, not just individual “firsts.”

Bearden’s institutional skepticism also comes through in later accounts of the era. A New Yorker profile of curator Thelma Golden, for instance, recalls that when Bearden was asked to join the Studio Museum in Harlem’s board in the late 1960s, he refused, suggesting he believed white people were using the museum for their own purposes—an anecdote embedded in a broader discussion of the period’s cultural politics and the founding of Cinque Gallery. Whether or not one agrees with Bearden’s assessment, the refusal signals his seriousness about power: who controls the narrative, who benefits from institutions, who gets to define Black art’s terms.

The art itself—especially the work that emerged from his mature collage practice—operates like an argument about power and memory, but it does so without didacticism. One of the enduring misconceptions about politically charged art is that it must announce its politics loudly. Bearden’s politics are often quieter and therefore, in some ways, more radical. To place Black domestic life—kitchens, bedrooms, front porches—at the center of the pictorial field is to contradict an art history that has often treated Black people as background, labor, or spectacle. The Romare Bearden Foundation has recently emphasized precisely this point, framing his attention to “the Black interior” as a profound elevation of private life into worthy subject matter. In Bearden, the ordinary becomes monumental.

This interiority is also intertwined with ritual. The Paris Review, reflecting on Bearden’s “Projections,” describes the breakthrough quality of the series and the way collage allowed him to reconstruct the visual world, with the works resonating alongside America’s struggle with “old ways of seeing and knowing.” That phrase—old ways of seeing—lands hard when you consider the historical context. In the mid-century United States, old ways of seeing were not only aesthetic conventions; they were racial hierarchies enforced through housing policy, policing, schooling, employment. To challenge those ways of seeing is to challenge the story the country tells about itself.

Bearden did not do this by painting slogans. He did it by building a counter-archive—one made from the very materials of mass media and everyday life. The National Gallery of Art, in an article on his process, notes that Bearden collected old magazines like Ebony and Jet as well as other printed materials, and that these source materials became part of how he constructed his collages. There is a quiet brilliance in that fact. Ebony and Jet were themselves crucial twentieth-century Black archives—repositories of faces, fashions, tragedies, triumphs, ordinary glamour. By cutting them into his art, Bearden was not cannibalizing Black media; he was transforming it into a permanent visual record inside the fine-art canon that had so often excluded Black documentation.

The act also complicates the idea of originality. A collage is built from what already exists. Bearden’s originality lies not in pretending otherwise but in making the transformation visible, in demonstrating that Black cultural production has always involved making something from what you have, sometimes because what you were owed was withheld. The seams are part of the meaning.

There is another dimension to Bearden’s story that complicates the standard artist biography: his proximity to sports, and the alternate life he might have lived. The Atlantic published a piece in 2012 recalling that before his renown, Bearden had been offered a chance to play professional baseball, a path he declined as he moved toward art. This anecdote can be read in multiple ways. On one level, it’s a humanizing detail—the artist as young man at a crossroads. On another, it underscores the narrow bandwidth of opportunity often extended to Black talent in the early twentieth century. Sports and entertainment were legible routes; fine art was not. Bearden’s decision, then, was not only personal preference. It was a wager against the assumptions of his time.

That wager paid off, but not because the art world suddenly became equitable. Bearden’s career unfolded through a landscape where Black artists were regularly undervalued, under-collected, and under-reviewed. His eventual recognition—major exhibitions, critical acclaim, institutional holdings—came through persistence and through work that could not be easily categorized. By the time of his death in March 1988, the Washington Post described him as a preeminent abstract painter and collage artist who fashioned stories of Black dignity; another Post piece, written as a critical appreciation, emphasized the musicality of his “pieced-together pictures,” their “bluesy subjects” and jagged rhythms. Even in mainstream language, the metaphor returns: Bearden’s pictures sound like something.

Sound, in fact, is one of the most persistent presences in his work. Bearden’s collages often depict musicians, dancers, club interiors, parades, and church gatherings—spaces where sound organizes community. The Bearden Foundation has explicitly framed his work as moving with the rhythm of jazz, portraying music not as background entertainment but as cultural architecture. This matters because music has long been one of the most internationally recognized forms of Black American art, sometimes to the exclusion of visual art. Bearden’s genius was to translate that musical logic into images without reducing music to mere iconography. The pictures don’t just show musicians; they behave musically: repetition, variation, syncopation, call-and-response among visual motifs.

This musicality also helps explain why Bearden’s work is so frequently invoked as a template for contemporary practices like sampling and remix. Long before “sampling” became a dominant music production technique, Bearden was sampling images. He was pulling from printed culture, from personal memory, from art history, and re-composing those materials into a new arrangement. The method anticipates much of what we now think of as postmodern and contemporary: the collapse of high/low distinctions, the recycling of media, the critique of “original” authorship. But Bearden’s work avoids the cynicism that can accompany those gestures. His collage is not ironic. It is tender. Even when it depicts hardship, it refuses despair as the only story.

That tenderness is crucial to his lasting power, and it is one reason scholars resist reading him as simply “nostalgic.” Yes, Bearden’s work often draws on memory of the South and of earlier Harlem scenes. But memory, in his hands, is not escape; it is resource. It is material. It is a way of carrying what might otherwise be lost. The Romare Bearden Foundation has recently emphasized the relationship between his art and community building, framing creativity as a tool for cultural empowerment and a form of activism. Even when one reads such institutional framing with appropriate caution—foundations have their own narratives to maintain—the underlying idea aligns with what the work itself demonstrates: Bearden’s pictures are communities in miniature.

Consider his engagement with epic narratives and myth. In 1977, he created a cycle of collages and watercolors based on Homer’s “Odyssey,” often referred to as the “Odysseus Series.” Columbia’s Wallach Art Gallery describes the series as a bridge between classical mythology and African-American culture, rich in symbolism and allegory. This is not a simple act of “elevating” Black life by attaching it to a Western canon; it is a reshaping of that canon, an insistence that Black experience belongs not only to American history but to the deep structures of story. Bearden’s Odysseus is not a marble hero. He is a traveler shaped by displacement, improvising his way home through forces larger than himself. For a people whose history includes forced migration and the long search for belonging, the parallel is not decorative—it is structural.

The significance of that structural move becomes clearer when placed against the art-world debates of Bearden’s time. Modernism, in its most institutionalized form, often pretended to be universal while remaining culturally specific—white, Euro-American, classed. Bearden’s work exposes this pretense by proving that Black cultural specificity can generate formal innovation, not merely content. He does not “add” Black subjects to a preexisting modernist language; he reshapes the language. The result is a Black modernism that is not derivative but generative.

That generative force is also visible in the way Bearden’s work has been conserved, studied, and taught. Institutions like the National Gallery of Art now treat his materials—his piles of printed sources, his process artifacts—as crucial evidence of how the work was made. This is a form of validation that goes beyond hanging pictures on walls. It is an acknowledgment that process matters, and that the labor of constructing Black images is part of the historical record.

But Bearden’s legacy is not only about institutional embrace. It is also about what his work continues to make possible for artists navigating the same questions of visibility and autonomy. Cinque Gallery’s records, preserved and described by the Smithsonian, are one piece of that continuity: a paper trail of a space created to nurture artists who were “unknown” or neglected by mainstream systems. When we talk about Bearden’s significance, we should talk about that paper trail the way we talk about his collages: as an archive assembled against erasure.

This is where Bearden becomes especially relevant to contemporary conversations about representation, patronage, and gatekeeping. The last decade has seen waves of institutional reckoning—museums diversifying collections, galleries elevating overlooked artists, foundations funding “equity” initiatives. These shifts matter, but they can also mask a deeper continuity: Black artists have always had to build parallel structures when mainstream ones failed them. Bearden understood this, and his life offers a case study in how an artist can operate on both fronts—inside the canon and outside it, seeking recognition while also building alternative routes.

His death in 1988, reported widely, closed the book on a life that had spanned the better part of the American century. Yet his afterlife in American culture has only grown. Part of this growth is driven by exhibitions and scholarship. Robert G. O’Meally—editor of “The Romare Bearden Reader”—has written about Bearden and helped situate him within broader cultural histories, emphasizing his role not only as an artist but as a thinker whose work intersects with literature and music. This multidisciplinary framing is appropriate because Bearden’s art is itself multidisciplinary: a visual literature, a paper symphony, a city map made of remembered rooms.

Another part of his afterlife is driven by the way his work continues to feel contemporary. In an era dominated by digital collage—memes, Photoshop composites, algorithmic remix—Bearden’s analog scissors-and-glue practice can look prophetic. But it would be a mistake to treat him simply as a precursor to contemporary aesthetics. His work matters because it is ethically charged. It asks what it means to assemble a people’s image when that image has been distorted. It asks what it means to make beauty without making prettiness, to make celebration without denial, to make art that honors the ordinary.

His pictures insist that Black life contains epic narrative and small domestic drama, mythic archetype and personal idiosyncrasy. They insist that a Harlem block can be as worthy of monumental treatment as any classical landscape. They insist that fragments are not evidence of brokenness; they are evidence of survival.

To sit with Bearden’s collages is to confront a particular American paradox. The country has long celebrated “innovation” and “originality,” yet it has often forced Black Americans to innovate merely to exist within systems designed to exclude them. Bearden turns that forced innovation into a chosen language—one that makes the seams visible and thereby makes the truth visible. The truth is not only that Black life has been fragmented by history. The truth is also that Black life has been endlessly reassembled into community.

That may be Bearden’s most enduring gift: not a single image, not a single series, but an ethic of assembly. In his hands, collage becomes a way to say: we are here, we have always been here, and our stories can be built from what you tried to throw away.

And if his work can feel, at moments, almost unbearably generous—so much life packed into so many cuts—it may be because Bearden understood something profound about American memory. Memory is not a stable photograph. It is an argument, a reconstruction, a negotiation between what happened and what survives. Bearden made that negotiation visible. He made it beautiful without making it easy. He made it musical without making it mere entertainment. He made it American without letting America pretend it did not belong to him.

In the end, to call Romare Bearden a “collagist” is accurate but insufficient. Collage was his tool. His subject was a people. His accomplishment was to give that people—not as symbol, not as sociological category, but as living community—the scale, complexity, and formal invention that the American canon had too often reserved for others.

More great stories

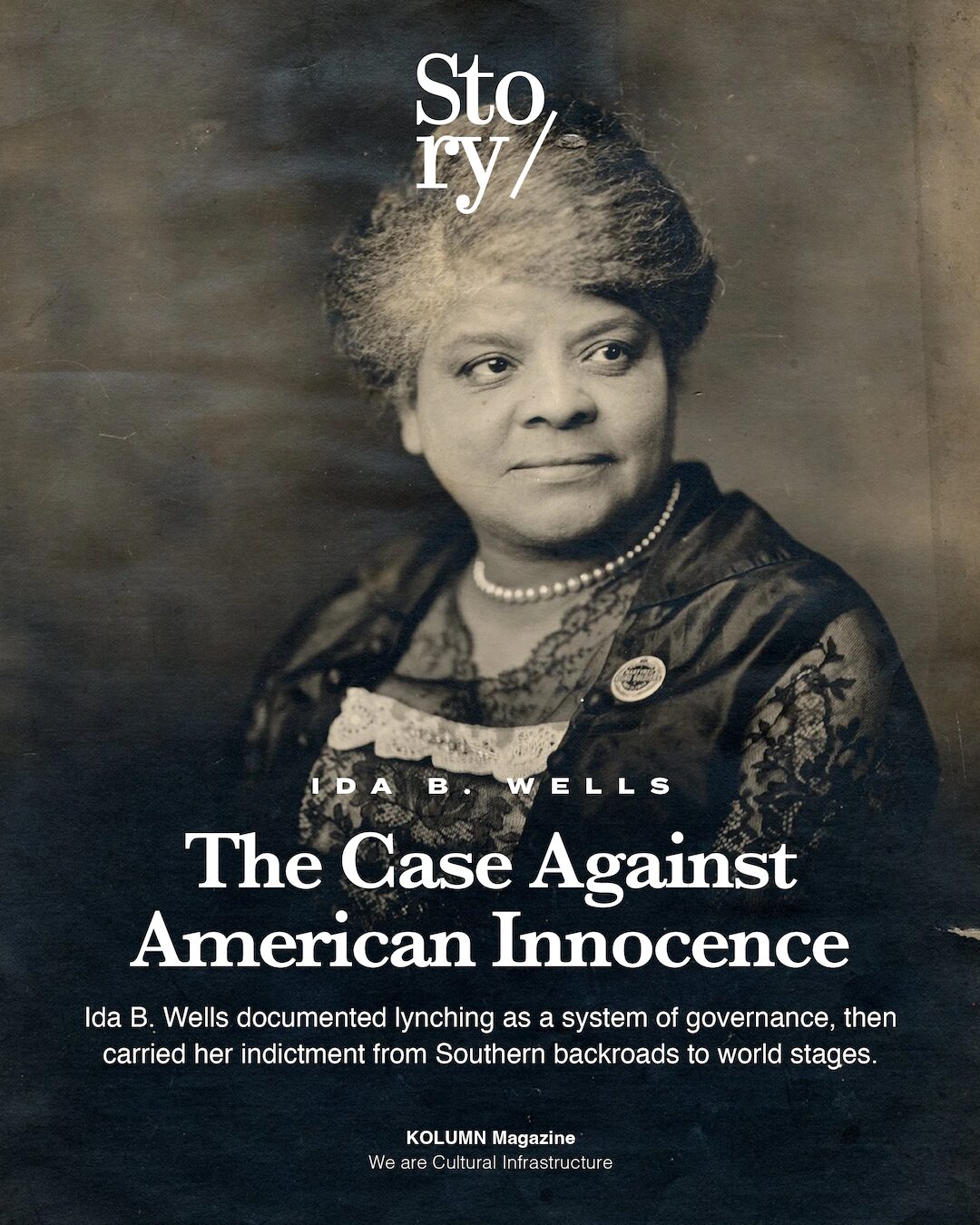

Ida B. Wells: The Case Against American Innocence