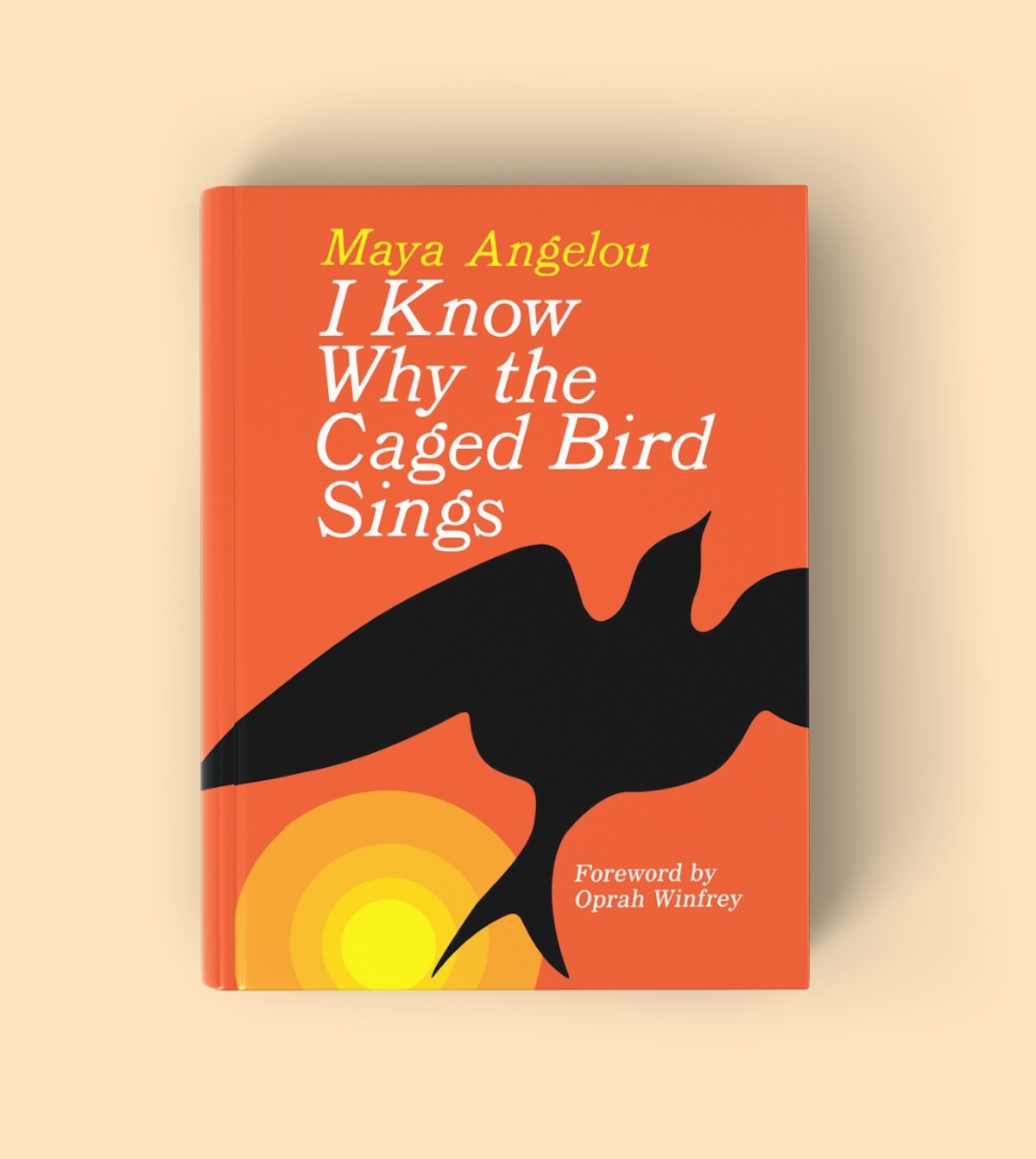

A work that has lived for decades in the double condition reserved for American classics by Black women: revered, assigned, and perpetually put on trial.

A work that has lived for decades in the double condition reserved for American classics by Black women: revered, assigned, and perpetually put on trial.

By KOLUMN Magazine

Every few generations, a single book becomes more than a book. It becomes a dispute, a ritual, a password. People who love it speak about the first time they encountered it the way others speak about a first church service or a first heartbreak: the room, the weather, the feeling that something permanent had been touched. People who want it removed rarely quote it closely; they tend to gesture at it—too explicit, too angry, too grown—like a warning label on a bottle they never opened. This is the long afterlife of I Know Why the Caged Bird Sings, Maya Angelou’s 1969 autobiography of childhood and adolescence, a work that has lived for decades in the double condition reserved for American classics by Black women: revered, assigned, and perpetually put on trial.

Angelou’s memoir begins in humiliation—young Maya imagining herself exposed before a congregation, a child trying to manage the public terror of being looked at and found lacking. That opening mood matters because it is not merely personal. It is a grammar of race and gender: the Southern Black girl as an early student of other people’s contempt, required to translate it before she is old enough to name it. The book ends, famously, with a birth—Maya at sixteen becoming a mother—an ending that refuses the tidy satisfactions of “overcoming” while insisting on something harder: continuation. That arc—shame to speech, silence to song—helps explain why the book has remained culturally adhesive for more than half a century, and why institutions keep trying to decide whether it should be publicly available at all.

To write about Caged Bird today is to enter a crowded room. There is the room of literature, where Angelou is discussed as a stylist and a structural innovator—an autobiographer who wrote with the pacing and scene-building of a novelist. There is the room of history, where her childhood map—Stamps, Arkansas; St. Louis; San Francisco—becomes a guided tour through the social architecture of Jim Crow and the war-era West. And there is the room of public policy and moral panic, where her memoir is repeatedly treated as contraband: among the American Library Association’s most frequently challenged books, and cited in reports documenting prison censorship and institutional bans that reframe depictions of sexual assault as “security threats.”

Angelou’s achievement is that the book survives all these rooms without shrinking to fit any single one. It is not only a coming-of-age story. It is not only a testimony of trauma. It is not only a political text, though it is political in the way any honest account of Black life in America becomes political the moment it is told plainly. Caged Bird is also, at its most durable level, a study of language itself—how it can be used to injure, and how it can be used, painstakingly, to rebuild a self.

1969: The moment a private life became public argument

Angelou published I Know Why the Caged Bird Sings in February 1969, at the hinge of an American decade. The Civil Rights Movement had made landmark gains, and the country was also deep in backlash, policing, and exhaustion. The assassinations of Martin Luther King Jr. and Robert F. Kennedy were recent wounds; cities were still burning in memory and sometimes in fact. A political vocabulary of “law and order” was hardening into national policy. In that landscape, Angelou offered not a manifesto but an interior. She wrote a Black girl’s childhood as a serious subject, full of specificity and bruised comedy and dread, and she treated the private details that polite society preferred to render invisible—rape, muteness, hunger, the daily calculations of dignity—as the actual material of American life.

Part of what made the book disruptive was its genre-bending clarity. Angelou was not inventing Black autobiography, but she was changing what many Americans believed it could contain—especially when written by a Black woman. The book’s critical reception, and its subsequent canonization, have often been described in those terms: a new kind of memoirist, someone who could place Black interior life at the center without apology. But the public conversation around the book also revealed something less flattering: that the same culture that praises “authentic stories” often panics when authenticity refuses to be discreet.

Even the title is a kind of argument. Angelou pulled it from “Sympathy,” Paul Laurence Dunbar’s poem in which a caged bird sings not because it is happy but because it is desperate—singing as longing, as protest, as survival. (The Poetry Foundation) In Dunbar, the bird’s song carries the paradox that becomes Angelou’s organizing principle: the voice that emerges under constraint. By adopting that line, she ties her personal narrative to a lineage of Black expression that had already learned how to translate captivity into art. The title is also a promise to the reader that the book will not be a mere catalog of suffering; it will be, in the end, an account of how a voice is made.

Stamps, Arkansas: The laboratory of Jim Crow

If Caged Bird is a national classic, one reason is that it is built like a sequence of rooms you can walk through. The Stamps chapters remain among the most vivid depictions of small-town Jim Crow in modern American literature: the general store operated by Momma (Annie Henderson), the rhythms of church life, the brittle boundaries between Black and white spaces, and the constant, ambient knowledge that white people can reach into Black life at will.

Angelou’s genius in these chapters is her double vision: she writes Stamps with the sensuous detail of a child—smells, textures, the comedy of local characters—and with the adult’s awareness of what that detail signifies. Her style is frequently described as novelistic, and it is: scenes unfold with dialogue that carries social meaning, and with descriptions that turn ordinary objects into symbols of a segregated economy. the book resists the sentimentality that sometimes attaches to memoirs of childhood. Stamps is not an Eden lost. It is a place where safety is partial, negotiated, conditional—and where the Black community’s cohesion is both a shelter and a response to threat.

One of the book’s most remembered Stamps sequences involves humiliation that is also theater: young white girls mocking Momma outside her store, attempting to provoke the kind of reactive anger that segregation could punish. Momma’s restraint reads, in Angelou’s telling, as a kind of weaponized dignity—an embodied lesson about survival in a system that is designed to criminalize Black feeling. Readers have returned to that scene for decades because it dramatizes a recurring Angelou theme: self-respect as something you practice in public even when nobody else is practicing respect toward you.

This is not the kind of “uplift” that denies reality. It is closer to what the memoir keeps revealing: that dignity under Jim Crow often required a choreography of withholding. You do not say what you think. You do not move too fast. You do not invite trouble, because trouble is already invited. That reality becomes the psychological groundwork for what happens later in the book—how a child can learn to equate silence with safety.

The rape, the trial, the muteness: A memoir that refuses euphemism

There is no way to discuss Caged Bird honestly without discussing the sexual assault that sits near its center. Angelou recounts being raped at eight years old by her mother’s boyfriend in St. Louis, and she narrates the aftermath with a precision that many readers encounter as both devastating and strangely controlled.

What follows is one of the most psychologically astute passages in twentieth-century autobiography: Maya’s decision to stop speaking after the man is killed—murdered, Angelou suggests, by relatives after he avoids serious punishment. Maya believes her words have killed him; she believes language is lethal. And so she retreats into a near-mute existence, speaking only to her brother, living inside a belief that silence can prevent further harm.

This is the portion of the book that has triggered some of the most persistent censorship efforts, often framed in the language of “protecting children.” The irony is painful and obvious: the memoir’s depiction of assault has been treated as more dangerous than the conditions that make assault possible. In school-board disputes and prison bans alike, “sexual content” becomes a label that collapses testimony into obscenity.

A report from Howard University’s Thurgood Marshall Civil Rights Center, for example, describes how prison systems have banned books through content-based rationales and cites Caged Bird specifically: the North Carolina Department of Public Safety once banned Angelou’s memoir because its depiction of sexual assault was deemed a “security threat.” That phrasing—sexual assault as security threat—illustrates how bureaucracies can transform a victim’s account into contraband, effectively punishing speech about violence as though it were violence itself.

The American Library Association’s challenged-books data places I Know Why the Caged Bird Sings among the most frequently challenged titles across multiple decades, a fact that functions like a cultural barometer. The book’s repeated appearance on those lists underscores that the controversy is not episodic; it is structural. The push to remove the memoir resurfaces whenever institutions feel pressure to sanitize narratives about race, sexuality, and power.

Yet Angelou’s depiction of the rape is also inseparable from the book’s core subject: what it takes to come back from the place where language fails. The story is not simply that trauma occurs; it is that trauma rearranges the relationship between a person and speech. That is why the character who becomes almost mythic in the memoir—Mrs. Bertha Flowers—matters so much.

Mrs. Flowers and the craft of being given back to yourself

In the cultural memory of Caged Bird, Mrs. Flowers is often recalled as a gentle rescuer. Angelou writes her more precisely than that: Mrs. Flowers is a pedagogue of voice. She does not only encourage Maya to read; she teaches her how to inhabit words as a living instrument. The scenes between them are some of the book’s most important because they show literature functioning not as escape but as re-entry into the world.

Angelou’s portrait of Mrs. Flowers insists that speech is not simply produced; it is cultivated. Words must be “heard” in the mouth, carried in the body. The lesson is aesthetic and moral at once: language can be a form of care, a method of restoring agency after violation. For generations of readers, those pages have been the memoir’s hinge, the moment when a book about pain becomes a book about technique—how a person learns, slowly, to translate experience into meaning without being consumed by it.

The memoir’s fascination with language also explains why it continues to resonate beyond the specific facts of Angelou’s life. It is, in part, a story about literacy as survival. Books appear in the narrative not as decorative references but as tools that stabilize an identity that the world keeps trying to rename, diminish, or erase. That theme has become more visible in recent years as the politics of what children are allowed to read has intensified—and as “banning” has moved from isolated complaints to coordinated policy and institutional purges.

San Francisco and the making of a modern Black girlhood

One of the quieter revolutions of Caged Bird is geographic. The memoir refuses to treat Black life as only Southern. It is a migration story as much as it is a childhood story: from Arkansas to St. Louis to California, from the rural South’s rigid caste system to the West Coast’s different, less legible forms of exclusion and possibility.

In San Francisco, Angelou becomes something else—still vulnerable, still encountering racism, but also closer to the idea of choice. She attends George Washington High School. She studies dance and drama. She pushes against the labor market’s racial barriers and becomes the first Black female cable car conductor in San Francisco, an episode that the memoir uses to dramatize determination as a daily practice rather than a slogan.

These chapters matter because they expand the book’s emotional palette. In Stamps, the cage is obvious: segregation is explicit, its punishments immediate. In California, the bars are different—employment discrimination, social alienation, the policing of Black girls’ bodies and ambitions—but the memoir suggests that the capacity to imagine a future can itself be an act of resistance. This is a key part of the book’s significance for readers who are not from the South, and for those who recognize that racism is not one regional style but a national system with local dialects.

The West Coast chapters also allow Angelou to explore adolescence as uncertainty rather than moral lesson. She writes about desire, confusion, insecurity, and the pressure to define oneself in a world that offers Black girls a limited menu of identities. One of the reasons the book remains taught is that it does not sentimentalize girlhood. It respects the complexity of becoming.

Style as strategy: Why the book reads like a novel and hits like testimony

Critics and admirers have long noted that Caged Bird is written from life but shaped with conventions of fiction: scene, character, suspense, humor, pacing. Angelou’s prose often moves with the momentum of oral storytelling—its punch lines timed, its repetitions purposeful, its metaphors tactile. She can describe a storefront, a Sunday service, a bus ride, and make each feel like a small stage where American power is performed.

This is not accidental artistry; it is part of how the memoir claims authority. In the United States, Black women’s testimony has often been doubted, minimized, or reframed as exaggeration. Angelou answers that cultural habit not by pleading but by composing. She gives the reader scenes that are difficult to dismiss because they are so fully realized. Even when a reader does not share her experience, the writing forces recognition: this is what it felt like; this is how it sounded; this is what it did to a child’s mind.

The Washington Post’s archival framing of the book’s early reception underscores how strongly critics responded to that composure. In 1970, the Post’s review praised the memoir’s “distance”—the sense that Angelou could be “outside and inside at the same time,” a double vision that allowed her to narrate her childhood without losing control of the story. That quality—control without coldness—is one of the memoir’s defining achievements. It is a trauma narrative that refuses to be sensational. It is candid but not confessional in the modern, performance-driven sense. It is closer to an architecture: she builds a structure strong enough to hold what she is willing to place inside it.

This also explains why the book can be, for many readers, physically affecting. It invites tears, yes, but it also invites a certain kind of steadiness: a sense that telling the truth can be an act of craft rather than an act of collapse. In the Post’s reprinted archival interview, Angelou described the writing process as emotionally punishing—crying through nights, forcing herself through the work. The book’s endurance suggests that readers can feel that labor embedded in the sentences.

The challenged-book phenomenon: What it means when a classic is treated like contraband

The most predictable chapter in the public life of Caged Bird is the recurring attempt to remove it from shared space. The American Library Association’s lists of frequently challenged books show the memoir appearing across multiple decades—ranked among the most contested titles in the 1990s, and remaining prominent in the 2000s and 2010s.

This recurring challenge is often described as a response to the book’s depictions of rape and to its frank treatment of racism and sexuality. But the deeper pattern is about authority: who gets to name reality, and where. When a school district removes Caged Bird, it is not only making a claim about “age appropriateness.” It is making a claim about whether students should be allowed to encounter a Black girl’s account of violence and survival as literature rather than rumor.

Word In Black, in a piece about banned books by Black women, describes Caged Bird as the first of Angelou’s autobiographical series and notes that it has faced a “string of bans and removals” in the United States, citing challenges dating back years, including a 2001 dispute over a high school reading list. The detail matters because it shows how these battles travel: one challenge becomes precedent; precedent becomes a script; the script is reused in the next town, the next year, the next political moment.

The same dynamic appears in a Word In Black item on Banned Books Week that quotes a bookstore card describing why Angelou’s memoir was added to a banned-book display—“language and portrayal of violence, racism, sexuality, and teen pregnancy”—a summary that reads like an indictment of reality rather than of writing. The categories are revealing: violence and racism are treated as pollutants, even when the book’s entire ethical argument is that refusing to name those forces does not make them disappear.

The prison context is even starker. The Thurgood Marshall Civil Rights Center report places Caged Bird within a broader pattern of arbitrary bans that restrict incarcerated people’s access to books significant to African American history and culture. When institutions ban Angelou’s memoir in prisons, they are not protecting children. They are controlling adults. They are treating narrative as a threat.

And in the current era, the book’s censorship story has moved into the realm of national news. In 2025, the Associated Press reported that I Know Why the Caged Bird Sings was among nearly 400 books removed from the U.S. Naval Academy library amid a directive to purge materials associated with diversity, equity, and inclusion. Whatever one thinks of the specific politics of that moment, the inclusion of Angelou’s memoir in such a sweep is symbolically blunt: a foundational American autobiography by a Black woman treated as suspect not because it is obscure, but because it is canonical—and because canon can be contested.

These episodes do not merely demonstrate that the book is “controversial.” They demonstrate that it functions as a diagnostic. When Caged Bird is targeted, it is often a signal that institutions are being asked—by organized pressure, by political climates, by administrative caution—to narrow the bandwidth of permissible truth.

Why the memoir keeps returning in the age of #MeToo and “DEI” backlash

Angelou wrote about childhood rape decades before contemporary movements created common language for sexual violence, consent, grooming, and trauma. That fact has become central to the book’s modern relevance, particularly for readers who encounter it as teenagers and suddenly recognize their own experiences in its pages. Time, reflecting on Angelou’s life and influence, has emphasized how her 1969 memoir addressed sexual trauma long before it was widely discussed in mainstream culture.

But Caged Bird also speaks to the current moment because it refuses the neat binary that public debate often demands: victim or hero, damaged or triumphant. Angelou writes a self that is complicated—sometimes ashamed, sometimes funny, sometimes cruel, sometimes bewildered, sometimes determined. That complexity is what makes the book a sustained education in empathy rather than a curated performance of inspiration.

In a Guardian review, the memoir’s emotional arc is framed as a movement from inferiority complex to confidence, aided by literature and by the intervention of Mrs. Flowers, and culminating in moments like Angelou becoming a trailblazing streetcar conductor. The review’s framing captures something essential: the book does not erase the pain; it simply refuses to let pain be the only plot.

At the same time, the book’s renewed targeting in modern censorship waves suggests that its frankness remains unsettling. If institutions are currently anxious about “DEI,” about what history should be taught, about what kinds of identity narratives belong in public education, then Caged Bird becomes an obvious target precisely because it is not abstract. It is not theory. It is a lived account of racism’s daily texture and sexual violence’s psychic aftermath. The book insists that America’s moral life is not primarily a set of ideals; it is a set of experiences distributed unequally.

That insistence is why the memoir still feels contemporary: it describes the kind of structural vulnerability that remains familiar to many Black girls, even when the surface conditions have changed. It also describes something that is not limited to race: how shame and fear can make silence feel like the only option, and how voice can be rebuilt through community.

Influence: What Angelou unlocked for Black women’s life-writing

When Caged Bird became widely celebrated, it did not merely launch Angelou’s own career; it also expanded the perceived possibilities of Black women’s autobiography. The broader critical conversation has frequently framed it as a watershed for Black women’s literature and for the public legitimacy of Black female interiority.

This influence is not only historical; it is formal. Angelou demonstrated that autobiography could be made with the tools of the novel without surrendering truth-claims. She showed that a Black woman could write her own body and mind as central text, not as supporting evidence for someone else’s narrative. She also helped normalize the idea that a life story could include sexual violence without being reduced to it—an aesthetic and ethical move that continues to shape memoir today.

The Root, in a Black History Month literary feature, describes Caged Bird as capturing the “longing of lonely children,” the “brute insult of bigotry,” and “the wonder of words” that can restore the world. That phrasing echoes what many readers experience: the book as a bridge between private loneliness and public recognition, between injury and art. It is also a reminder that the memoir is not a single-issue document. It contains joy, comedy, community portraiture, and the everyday ecstasies of language—precisely the things that make it literature rather than case file.

Ebony, writing in the aftermath of Angelou’s death, framed Caged Bird as the moment she “broke her silence,” emphasizing both the personal and cultural significance of that act—how fearlessness in telling her story carved out space for others. In another Ebony feature listing essential Angelou works, the magazine situates Caged Bird as a coming-of-age narrative in the Jim Crow South, foregrounding its role as a foundational text in a larger body of autobiographical work. Together, those pieces reflect how Black media institutions have understood the memoir not merely as a bestseller, but as cultural infrastructure: a text that helps people name their lives.

That phrase—cultural infrastructure—may sound contemporary, but it fits. Books like Caged Bird become part of the architecture of self-understanding. They travel through families, classrooms, book clubs, and libraries, offering language for experiences that might otherwise remain private and unprocessed. The battles over whether the book should be accessible are, in that sense, battles over infrastructure: who gets public resources for their reality, and who is told to keep it private.

What the cage reveals about the country that built it

The temptation, in writing about a beloved classic, is to treat its greatness as settled. But the story of I Know Why the Caged Bird Sings is not only a story of literary triumph. It is also a story about how the United States responds when a Black woman refuses to self-censor. The memoir’s “significance” is inseparable from the fact that it is still argued over—still challenged, still removed, still defended, still rediscovered by new readers who find in it not a relic but a mirror.

The easiest way to misunderstand the censorship controversies is to treat them as evidence of the book’s flaws. They are better understood as evidence of the book’s function. Caged Bird does what great memoir often does: it makes private pain public without turning it into spectacle. It insists on the moral seriousness of a Black girl’s interior life. And it demonstrates that voice is not the opposite of captivity, but one of the ways captivity is endured and resisted.

Dunbar’s caged bird sings “of freedom.” Angelou’s book sings of something even more specific: the slow, awkward, hard-won process of becoming someone who can tell the truth and stay alive afterward.

In that sense, the memoir’s continuing presence on challenged-book lists is not an embarrassing footnote; it is a continuation of the book’s central drama. The same culture that teaches children to admire “resilience” often recoils from the real narratives that resilience requires. Angelou’s memoir refuses to let readers enjoy the idea of survival without confronting the conditions that make survival necessary.

That refusal is why the book remains a classic. Not because it is comfortable. Because it is accurate. And because it reminds us—again and again—that the voice we celebrate is often the voice we first tried to silence.

More great stories

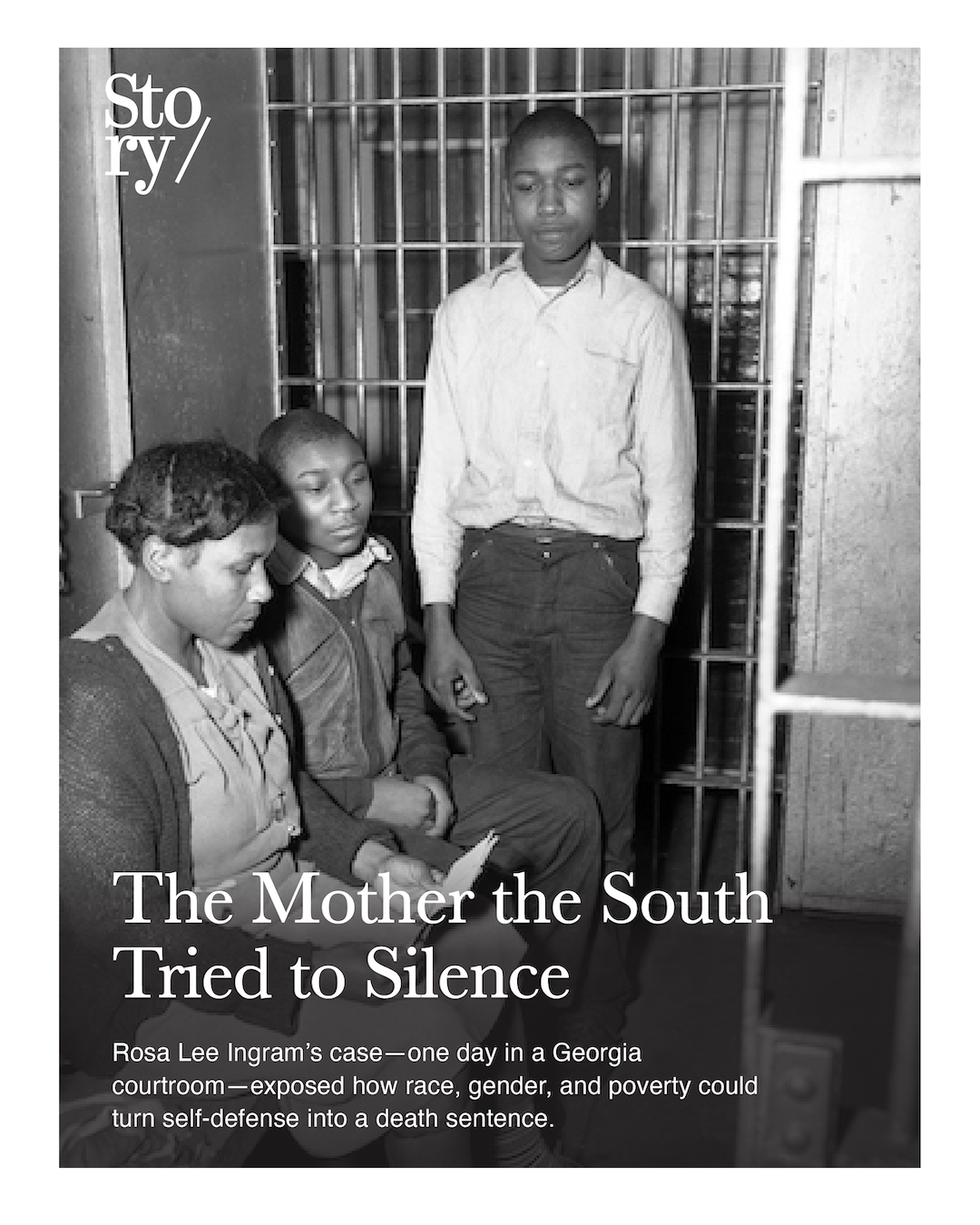

America’s Racist Cast of Characters