What is at stake is not the Obamas’ reputation; it is the public’s moral boundary. Dehumanization at the top of the political system does not remain “symbolic.” It contributes to the conditions under which people accept anti-Black policy outcomes—voter suppression framed as “integrity,” unequal policing framed as “order,” social abandonment framed as “personal responsibility.”

What is at stake is not the Obamas’ reputation; it is the public’s moral boundary. Dehumanization at the top of the political system does not remain “symbolic.” It contributes to the conditions under which people accept anti-Black policy outcomes—voter suppression framed as “integrity,” unequal policing framed as “order,” social abandonment framed as “personal responsibility.”

By KOLUMN Magazine

Late Thursday night, President Donald Trump shared a video on social media that included a racist animation depicting former President Barack Obama and former First Lady Michelle Obama with the bodies of apes. By Friday, after widespread condemnation, the White House removed the post.

To describe what happened as merely “offensive” is to understate how imagery like this functions in American life. The ape depiction is not a random insult that flared up in the heat of partisan argument; it is a revival—made frictionless by digital circulation—of one of the oldest dehumanizing tropes in the Western racial imagination. It belongs to a repertoire of racist stock figures that white Americans helped build, refine, and export through slavery, Jim Crow, advertising, popular entertainment, and political messaging. Those figures have names. They come with costumes, gestures, and scripts. And they have always done work—cultural work, commercial work, and, again and again, political work.

A useful place to start is with a distinction that often gets blurred in everyday conversation: the difference between an archetype and a stereotype.

An archetype is a recognizable story-shape: a recurring character model that shows up across texts and eras, a template audiences learn to identify almost instantly. Archetypes can be heroic or monstrous, comic or tragic, but they are durable because they feel “natural,” as if they were simply part of the way stories must be told. In the American racial context, many anti-Black archetypes were engineered precisely to feel inevitable—so that domination could be read as common sense.

A stereotype, by contrast, is a generalized belief about a group: a flattening claim that treats individuals as interchangeable examples of a presumed type. Stereotypes are cognitive shortcuts that become social weapons. They don’t just misdescribe; they constrain. They seep into hiring decisions, policing, schooling, housing, and healthcare; they shape what counts as “reasonable fear,” “credible testimony,” or “appropriate punishment.”

The relationship between the two is intimate. Archetypes are how stereotypes get dramatized. Stereotypes are how archetypes get smuggled into everyday judgment. Institutions then launder both into “culture”: a familiar cast in films and TV, a shorthand in headlines, a wink in campaign ads, a meme in a president’s feed.

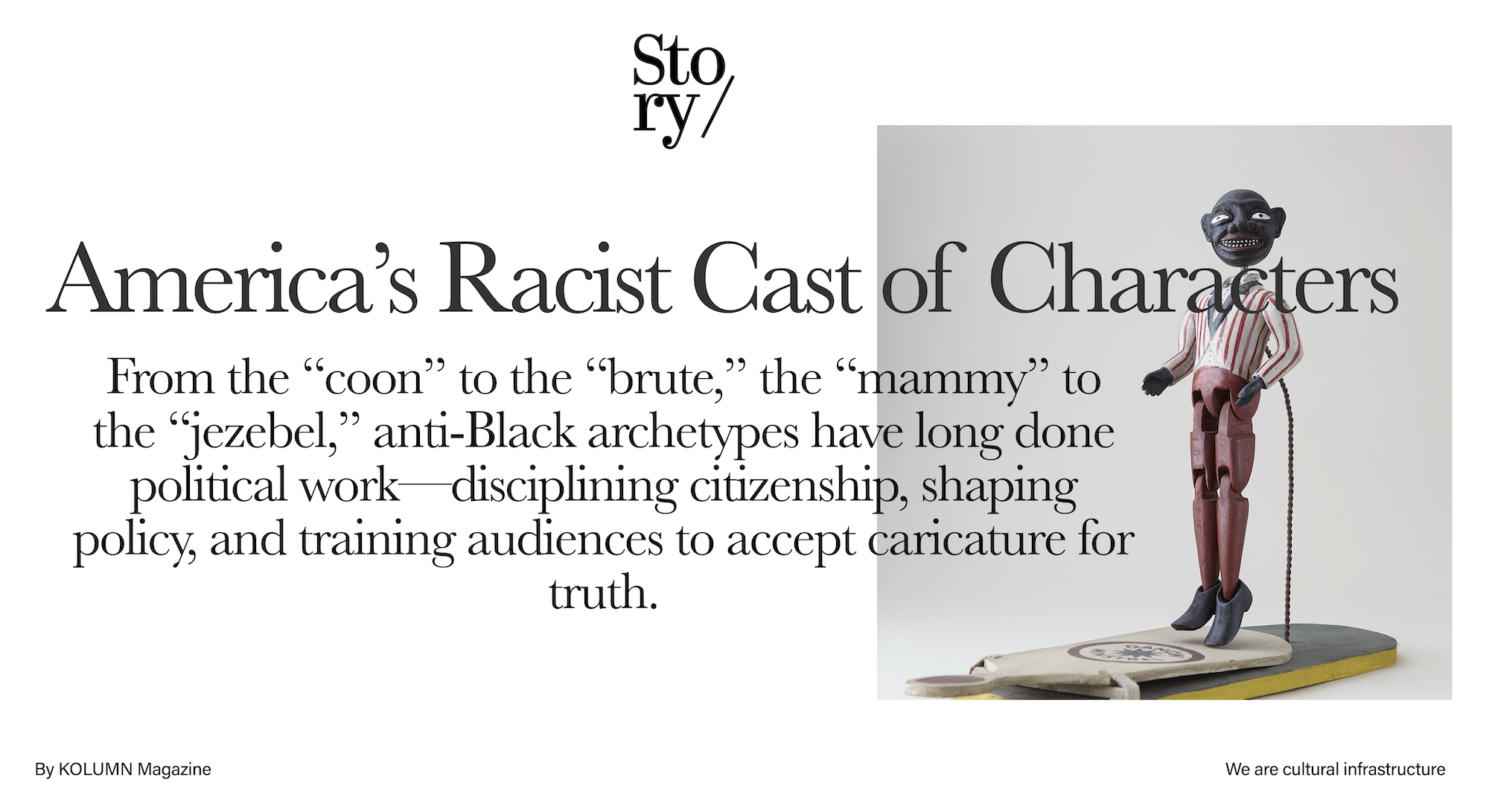

The National Museum of African American History and Culture has traced how these figures—especially those that emerged from slavery-era rationalizations and minstrel entertainment—became “popular and pervasive” scaffolding for American racial thinking, reinforcing social hierarchies in ways that outlast the eras that produced them.

What follows is not an exhaustive catalog of racist imagery. It is a focused look at seven depictions that have repeatedly organized anti-Black feeling in the U.S.—the Ape, Coon, Mammy, Brute/Black Buck, Jezebel, Pickaninny, and Uncle Tom—and at how each has been mobilized in politics and media, sometimes subtly, sometimes with brutal explicitness.

The ape: Dehumanization as political technology

Comparing Black people to apes is among the most direct forms of racial dehumanization, and that directness is part of its function. Dehumanization lowers the social cost of cruelty. It turns policy brutality into “order,” turns exclusion into “common sense,” turns laughter into permission. The power of the ape trope is not only that it insults; it that it suggests Black people are outside the moral community—less entitled to dignity, safety, and democratic belonging.

Researchers have documented how the Black–ape association has operated in U.S. culture and cognition even when people deny explicit prejudice; a prominent public discussion of this dynamic appeared in work by Phillip Atiba Goff and Jennifer Eberhardt, who examined the “ape image” as a persistent racial cue with real consequences for perception and punishment.

Historically, ape imagery draws from older European and American pseudo-scientific racial hierarchies and popular culture that depicted Africans as closer to animals than to Europeans. But in the United States it gained a particular political edge: it functioned as a justification for slavery and, later, for segregation and racial terror by presenting Black people as naturally unfit for citizenship, self-government, or equal rights.

That is why the president’s repost matters beyond the immediate outrage cycle. The office does not simply “share content.” It confers legitimacy—especially in the high-velocity, irony-soaked ecosystem of digital media, where the very act of posting can be defended as “just a meme.” When a president circulates an ape depiction of Black political figures—figures who symbolize Black accomplishment at the highest level of the state—he is not only insulting them. He is signaling to audiences that a core democratic boundary is negotiable: who counts as fully human within the political community.

And because archetypes are sticky, the ape does not stay confined to the post. It bleeds outward, connecting to older storylines: Black leadership as illegitimate, Black aspiration as laughable, Black intimacy as grotesque. It is a dehumanizing shorthand that becomes a permission slip for everything from harassment to policy retrenchment.

The coon: Comic degradation and the politics of “harmless fun”

If the ape trope is blunt-force dehumanization, the coon is a more socially agile weapon: it disguises contempt as humor. The Jim Crow Museum describes the coon caricature as one of the most insulting anti-Black caricatures—an adult figure portrayed as lazy, buffoonish, inarticulate, childish, unreliable. This caricature is dehumanizing in a different register: not animalization but ridicule, the insistence that Black adults are inherently unserious—incapable of discipline, intellect, or civic responsibility.

The coon’s political usefulness has always been its plausibility as entertainment. If the brute helps justify violence, the coon helps justify exclusion by “proving” that Black people cannot meet the demands of citizenship, professionalism, or leadership. It is the comic frame that turns inequality into a punchline, that makes “not taking them seriously” feel natural.

In the 19th century and into the early 20th, blackface minstrelsy was the mass medium through which these caricatures were standardized and sold. One influential character variant—“Zip Coon”—mocked free Black people who dressed well, spoke formally, or sought social mobility, portraying them as ridiculous imitators of white refinement. The Morgan Library and Museum notes that “Zip Coon” was a stock blackface character used to denigrate the manners of free Blacks, flourishing in minstrel repertoires in the 1830s.

Politically, this mattered because it targeted Black advancement itself. It trained audiences to see Black respectability not as dignity but as deception—Black aspiration as fraud. That sensibility has migrated into modern political rhetoric: the insinuation that educated Black leaders are “phony,” that they are performing a role they did not earn, that they are unnatural occupants of power. The coon archetype, updated, becomes the “clown” frame through which some media ecosystems treat Black politicians: their seriousness presented as a kind of audacity.

In film and television, Donald Bogle’s foundational work on Hollywood’s recurring Black character types traces how “coon” roles—variants of the comic fool—reappeared across decades, shaping what audiences came to expect from Blackness on screen. The deeper harm was not only that Black actors were limited to these roles, but that the public learned to consume Blackness as entertainment rather than as full humanity.

The mammy: A propaganda image of “happy servitude”

The mammy is one of the most enduring racist archetypes in American life because it packages domination as affection. She is imagined as loyal, nurturing, asexual, content to serve—proof, in the mythology, that slavery and later domestic servitude were not exploitation but a kind of family order. The Jim Crow Museum describes how the mammy image served the political, social, and economic interests of mainstream white America, deployed as evidence that enslaved Black women were “contented, even happy” in bondage.

This is an archetype with clear political utility. During slavery, it softened brutality with sentimentality: if the mammy loved the white family, then the plantation could be imagined as benevolent. During Jim Crow, it helped normalize Black women’s restricted labor options—especially in domestic work—by naturalizing service as “their place.” And in the consumer marketplace, mammy became a brand asset: an image used to sell food, household goods, and nostalgia.

The afterlife of mammy in American consumer culture is not theoretical. It has been visible on grocery shelves for generations—most famously in branding built around the “mammy” figure, which multiple outlets have described as rooted in minstrel-era imagery and racial stereotype, prompting corporate rebranding decisions in recent years.

Media has often treated the mammy archetype as “comfort”: the Black woman whose love and labor stabilize white households, whose interior life is secondary, whose own family is often absent or treated as irrelevant. In politics, the mammy’s logic echoes whenever Black women are expected to be the caretakers of democracy—mobilized as the party’s “base,” called on to rescue institutions that do not rescue them, praised for endurance while being denied structural change.

Patricia Hill Collins famously described “controlling images” of Black women—stereotyped roles that justify oppression while appearing natural—and the mammy sits near the center of that framework, shaping assumptions about Black women’s labor, temperament, and proper place.

The mammy archetype also clarifies something crucial about racist imagery: its harms are not only emotional or symbolic. They are material. An archetype that presents Black women as made for service can rationalize wage theft, workplace abuse, and the devaluation of Black women’s professional ambition. It can shape whose pain is believed and whose exhaustion is dismissed as normal.

The brute and the Black buck: Fear, sex, and the justification of violence

If mammy sentimentalizes domination, the brute—sometimes overlapping with the “Black buck”—does the opposite: it weaponizes fear. The Jim Crow Museum describes the brute caricature as a figure used to present Black men as menacing, dangerous, and violent, a portrayal that was prominently advanced in early American film and helped structure racial panic.

The brute is political propaganda with a body. It attaches danger to Black masculinity itself, often linking violence with sexual threat. In the Jim Crow era, this archetype worked in tandem with lynching culture: the story of Black male savagery—especially the alleged threat to white womanhood—functioned as a pretext for racial terror, disenfranchisement, and the expansion of coercive policing.

In media history, the brute’s influence is impossible to separate from early blockbuster filmmaking. The brute archetype was embedded in narratives that presented white supremacy as public safety, and Black presence as a problem requiring containment. That storyline did not vanish; it evolved. It shows up in crime reporting that overstates Black criminality, in political campaigns that frame urban Black communities as zones of disorder, in policy debates where punishment is treated as the primary form of governance.

The brute’s contemporary relevance is visible in how easily the word “thug” can operate as a racial proxy, or how images of Black protest can be framed as inherent violence while other forms of political rage are granted nuance. The brute archetype turns Black anger into a threat rather than a political claim, and Black self-defense into aggression.

The “Black buck” variant adds another layer: it casts Black men as physically powerful, sexually predatory, closer to animal impulse than human reason. It is an archetype that has long been used to police interracial boundaries and to justify surveillance, incarceration, and violence. And it affects media not only in what is shown, but in what is presumed: which suspects look “dangerous,” which victims look “innocent,” which neighborhoods look like targets.

This is one reason ape imagery is especially combustible when it touches political leadership. The ape trope and the brute/buck trope share a family resemblance: both are dehumanizing frames that justify exclusion and force. The medium changes; the function remains.

The jezebel: Sexual mythology as moral alibi

The jezebel stereotype constructs Black women as hypersexual, promiscuous, and sexually available—sometimes predatory—an image historically used to rationalize sexual exploitation under slavery and to blame Black women for the violence done to them. The Jim Crow Museum notes the jezebel’s centrality in popular culture, describing a persistent portrayal of Black women as sexually deviant, often reinforced by mainstream film tropes and pornography.

In politics, the jezebel functions as a moral alibi. If Black women are presumed sexually available, then white men’s abuse can be reframed as mutual desire; rape becomes “affair,” coercion becomes “temptation,” exploitation becomes “choice.” That is not just history—it is a continuing logic that can shape credibility in courtrooms and in public opinion, where Black women’s victimization is more easily doubted and more readily sexualized.

Media has recycled jezebel in multiple forms: the “video vixen” frame, the “fast” girl trope, the hypersexualized supporting character whose sexuality is treated as her defining feature. Even when presented as empowerment, these scripts can remain constrained by what the culture is prepared to recognize as Black femininity: either desexualized caretaker (mammy) or excessive desire (jezebel), with little room for complexity.

The Atlantic has explicitly connected modern media moral panics around Black women’s sexuality to the historical jezebel tradition, noting how public vilification can reproduce older narratives about Black female sexual excess. That line matters because it shows how archetypes do not require explicit racist language to operate. They can be activated through tone, framing, innuendo, and selective outrage.

Politically, jezebel also shapes “respectability” demands—who is allowed to be seen as a “good” woman worthy of protection. When Black women are punished for sexuality while other women are granted complexity, the jezebel archetype is doing its work.

The pickaninny: Anti-Blackness trained on childhood

The pickaninny—often spelled “picaninny” in archival contexts—is the caricature of Black children as dirty, animal-like, comical, and disposable. The Jim Crow Museum describes it as a dominant racial caricature of Black children, frequently depicted with exaggerated features and shown in grotesque scenes of danger or harm—chased, attacked, even used as “bait” in racist ephemera like postcards and advertisements.

This archetype matters because it reveals something chilling: racism does not wait for adulthood. It trains cruelty early by treating Black childhood as inherently unworthy of tenderness. The pickaninny image made it possible for mass audiences to laugh at Black children’s suffering, to see them as objects rather than children with inner lives.

In media history, the pickaninny is tied to the broader architecture of minstrelsy and commercial culture—dolls, toys, games, postcards—material that put racist training aids in the hands of families. The public broadcasting project “Many Rivers to Cross” has documented how Jim Crow–era racist images and messages served as propaganda to demean African Americans and legitimize violence.

Politically, pickaninny logic appears whenever Black youth are denied the presumption of innocence. It echoes in “adultification,” in school discipline disparities, in media coverage that frames Black children as older and more threatening than their peers. The caricature is old, but the habits it trained—what looks dangerous, what looks disposable—remain present.

The pickaninny is also a reminder that racist archetypes do not only police labor, sexuality, and crime. They police empathy. They tell the audience whose suffering counts.

The Uncle Tom: Loyalty as containment and betrayal as accusation

Finally, the Uncle Tom—or “Tom” caricature—is among the most politically charged archetypes because it is fundamentally about Black behavior in relation to white power. The Jim Crow Museum describes the Tom caricature as portraying Black men as faithful, happily submissive servants—born in antebellum America as part of slavery’s defense: if enslaved people were contented and loyal, slavery could be framed as humane.

Over time, “Uncle Tom” also became a common insult used within political discourse to describe a Black person perceived as excessively deferential to white authority or complicit in anti-Black systems. That evolution is complicated, in part because Harriet Beecher Stowe’s novel “Uncle Tom’s Cabin” has been interpreted in many ways, and because the stage and film versions often stripped the character of nuance. But the political function of the archetype is clear: it frames certain forms of Black accommodation as natural and others as betrayal, and it offers white audiences a comfort figure—proof, again, that the racial order is acceptable because some Black people appear to affirm it.

In media, Tom roles historically constrained Black male characters to servility—dependable, nonthreatening, grateful. In politics, the Tom archetype can become a tool for coalition management: rewarding Black leaders who reassure the status quo and punishing those who challenge it. It also becomes a wedge within Black communities, weaponized to police political strategy and identity.

Modern media still plays with this axis: the “safe” Black spokesperson versus the “angry” one; the “reasonable” Black voice that confirms dominant narratives versus the one described as radical or divisive. The Tom archetype is the shadow companion to the brute: one is the terror figure used to justify punishment, the other is the obedience figure used to justify paternalism.

Politics and media: Where these archetypes do their most reliable work

It is tempting to treat racist archetypes as relics—ugly antiques from a less enlightened time. The truth is harsher: they are durable because they are useful. They have been embedded into American political persuasion and mass media for so long that they can be activated quickly, sometimes with a single image, sometimes with a single insinuation.

Consider how neatly each archetype maps onto a political need:

The ape says Black leadership is illegitimate at the level of species.

The coon says Black civic capacity is unserious, laughable, unfit for power.

The mammy says Black women’s labor and sacrifice are natural and should be gratefully accepted without structural change.

The brute/Black buck says Black men are danger incarnate—policing and punishment are public safety.

The jezebel says Black women’s violation is self-inflicted—desire becomes guilt.

The pickaninny says Black children are disposable—empathy is optional.

The Uncle Tom says compliant Blackness is the only “good” Blackness—dissent becomes disloyalty.

This is why the modern meme ecosystem is not a break from history but, in certain ways, its acceleration. A racist postcard and an algorithmically boosted clip share a purpose: both distribute a script. Both invite the audience to feel something quickly, without evidence, and to treat that feeling as knowledge.

The Jim Crow Museum’s documentation of how old racist images are reproduced on new objects—and how “new racist forms” borrow from older caricatures—captures the continuity: images of “Sambos, Mammies, Toms, and Coons” repackaged for later eras, the archive constantly updated for new markets.

Digital culture intensifies a dynamic that has always defined racist caricature: plausible deniability. Minstrelsy could claim it was “just entertainment.” Advertising could claim it was “just branding.” Political campaigns could claim they were “just telling it like it is.” Memes can claim they are “just jokes.” But the function—disciplining who is recognized as fully human and fully American—does not depend on sincerity. It depends on repetition.

The presidential megaphone and the ethics of the moment

The fact pattern here matters. Multiple news organizations reported that President Trump shared a video containing a racist depiction of the Obamas as apes, that it sparked backlash, and that the White House later removed it. That is not an internet rumor; it is a documented event within the current political news cycle.

For journalists, the ethical challenge is twofold. The first is to cover the event without laundering the harm—without reproducing the imagery gratuitously, without turning spectacle into free distribution. The second is to supply the context that the meme format tries to erase. A meme wants to be consumed in isolation: a punchline with no history. Reporting must restore the missing history, because history is how the public understands what is at stake.

What is at stake is not the Obamas’ reputation; it is the public’s moral boundary. Dehumanization at the top of the political system does not remain “symbolic.” It contributes to the conditions under which people accept anti-Black policy outcomes—voter suppression framed as “integrity,” unequal policing framed as “order,” social abandonment framed as “personal responsibility.”

In that sense, the racist archetype is not merely an image. It is a political instrument—one the country has seen before, even when it pretends it hasn’t. The platform is new. The cast is old. The work remains the same.

The Long Arc of Anna Julia Cooper