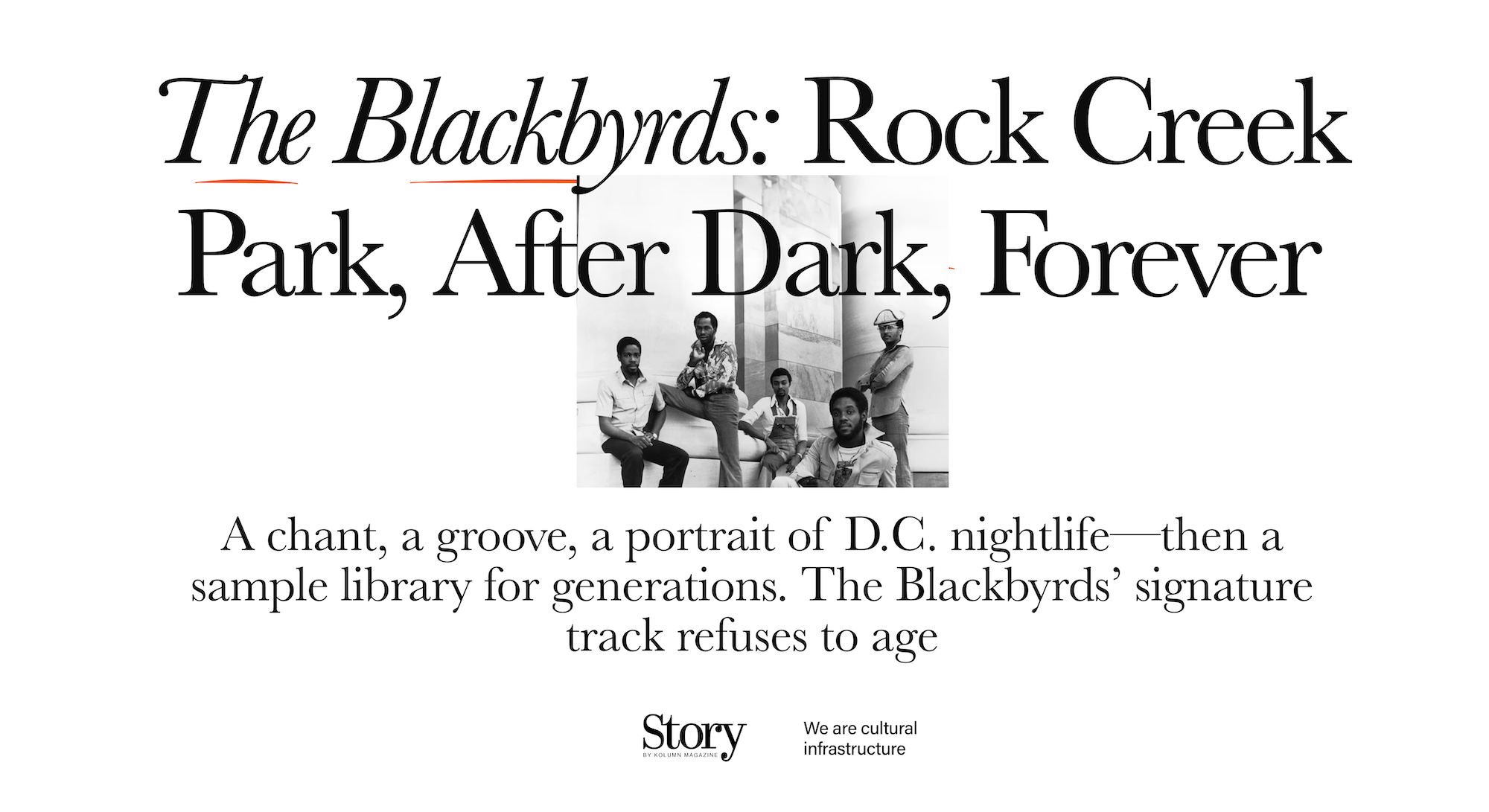

In a culture that cycles through trends at algorithmic speed, The Blackbyrds endure.

In a culture that cycles through trends at algorithmic speed, The Blackbyrds endure.

By KOLUMN Magazine

In the summer of 1975, a groove built for motion—light on its feet, precise in its pocket—crossed over in a way jazz-funk groups rarely managed without losing their identity. “Walking in Rhythm,” recorded the year before and released as a single, climbed into the upper reaches of the pop marketplace, hitting the Top 10 of the Billboard Hot 100 while also moving across R&B and adult-oriented formats. It sounded like ease, like a city that could still surprise you, like a band that knew how to be sophisticated without being precious. For listeners who came to it through the radio, The Blackbyrds could feel like an overnight success: a polished, hook-minded ensemble with horns that shimmered, rhythm guitar that clicked into place like architecture, and a sense that the air itself was warm.

But The Blackbyrds were never an accident of the charts. They were an argument—about what a Black jazz education could produce, about what a “crossover” could mean when it was driven by musicians who understood the lineage rather than running from it, and about how a group of young players from Washington could put their city into the nation’s headphones without asking permission. They were also a case study in the complicated bargain between artistry, economics, and mentorship in the 1970s: a decade when record labels hungered for funk’s immediacy, when jazz faced commercial pressure, and when a generation of Black musicians tried to build sustainable careers inside an industry that often profited most from their flexibility.

Half a century after their formation at Howard University under the guidance of Donald Byrd, The Blackbyrds remain one of the clearest examples of how institutional training and street-level rhythm can be fused into something durable—music that can sell records, fill dance floors, and later become foundational source material for hip-hop’s architecture of sampling. Their legacy is not simply that they had hits. It is that they built a vocabulary—bright, economical, unmistakably Black—that taught multiple eras how to move.

The origin story is a curriculum—and a business plan

The most important fact about The Blackbyrds is not a chart position or a gold certification, though they earned those. It is that they were designed. Their birth, as the group itself has described it, came out of a pedagogical idea: expose students to the “real world” of music, bridge the gap between academia and professional life, and do it not through abstract exercises but through the actual machinery of recording, touring, and selling records. That framing matters because it positions the band as a project with stakes—an experiment in what happens when a university’s talent pool is treated not as a finishing school but as a launchpad.

In this telling, Donald Byrd is not merely a famous name attached to the backstory. He is the architect. Byrd was already a major figure in jazz long before the band assembled, and by the early 1970s he had become deeply engaged in questions that were both musical and economic: how to keep jazz musicians working, how to speak to a younger Black audience, how to make records that could live in clubs and on radio without feeling like compromise. The Guardian’s obituary of Byrd notes that he formed The Blackbyrds from a pool of his students at Howard University and pursued commercial success through funk and soul-inflected projects, a move that could be “lucrative” even when critics questioned its artistic direction.

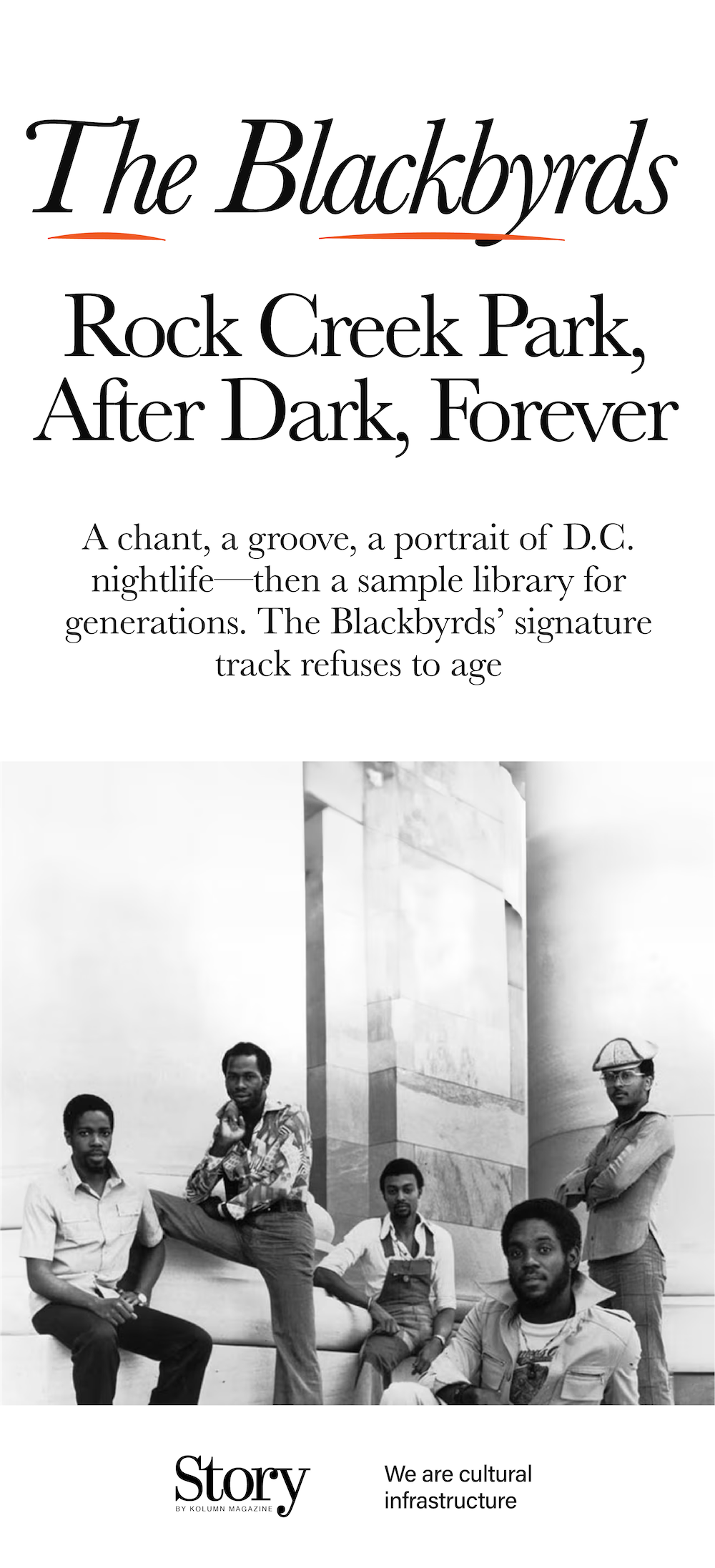

That tension—lucrative versus respected, danceable versus “serious”—was not unique to Byrd. It was the atmosphere of the decade. But Byrd’s approach made the classroom an engine for the marketplace. The Blackbyrds were assembled from Howard’s music department, with members who could read, arrange, and execute, but who also understood groove as a language and not a theoretical concept. A widely circulated biography describes the initial lineup as young musicians—including Keith Killgo, Kevin Toney, Joe Hall, Allan Barnes, Barney Perry, and Pericles “Perk” Jacobs—brought together through Byrd’s mentorship alongside label figures and producers who recognized what the combination could yield.

Even their name carries the imprint of a strategy. The group’s name was derived from Byrd’s successful album “Black Byrd,” tying the ensemble to a proven brand identity—jazz credibility with a funk-forward sheen. In other words, the project did not hide from commerce; it was built with commerce in mind, not as capitulation, but as survival and reach.

The most revealing detail in the group’s own account is how quickly the “real world” asserted itself. The Blackbyrds describe their formation as something that involved record executives and producers, including people associated with Fantasy Records and influential producer Orrin Keepnews. From the start, the band existed at the intersection of mentorship, institutional prestige, and label expectations. That is the intersection where many Black artists have historically been asked to perform: be excellent, be accessible, and do it fast.

But if The Blackbyrds were designed, they were not manufactured. Their sound—crisp, layered, hospitable to melody—reflects a group that understood how to write for the listener without flattening the musicianship.

Washington, D.C., as both setting and subtext

It is easy to flatten Washington into symbols: monuments, power, bureaucracy. But the Washington that made The Blackbyrds possible was a Black city with a dense ecosystem of schools, go-go incubation, jazz lineage, churches, parks, and neighborhoods that held both aspiration and pressure. The Blackbyrds’ story is inseparable from that D.C. reality, even when the band recorded elsewhere or toured nationally.

Listen to “Rock Creek Park,” and you hear a city rendered not as politics but as sensation. The hook is famously minimal—more chant than narrative—and that is part of the point. The song is about atmosphere: nighttime, bodies, breath, the park as a space where people move outside surveillance and into their own rhythms. Decades later, in a Washington Post interview, drummer and vocalist Keith Killgo recalled that the groove emerged while the band was opening for The Commodores, that two ideas (“Rock Creek Park” and “Happy Music”) took shape as grooves first, and that the lyrics arrived almost as an instinctive response to feel. The song, he suggested, sounded like the park—an embodied geography.

That interview also contains the kind of detail that signals genuine legacy: Killgo recounting a young person in France telling him he had “never been to Rock Creek Park” but went there “every day” through the record. This is what it means for music to export a place. You do not need a passport; you need a loop.

A later profile of the group in Howard’s student newspaper, published around the band’s 50th anniversary, underscores how central “Rock Creek Park” and “Walking in Rhythm” remain to the group’s identity and how explicitly the band is still understood as a Howard-born project. It is notable, too, that community memory keeps attaching their songs to local pride. The Blackbyrds are often described, especially in Washington-area coverage, not as a national act that happened to come from D.C., but as a D.C. act whose success validated the city’s musical sophistication.

This matters because Washington’s Black cultural history is often narrated through politics—the civil rights movement, federal employment, the language of representation. The Blackbyrds insist on a different story: the story of Black leisure, Black romance, Black nightlife, Black musicianship as craft, and Black public space as inspiration.

The sound: Where jazz discipline meets funk’s democracy

The Blackbyrds are sometimes grouped into “jazz-funk,” a label that can be either useful or reductive. Useful because it signals the blend—horn-driven lines, improvisational fluency, R&B backbeat. Reductive because it can imply a generic fusion project. The Blackbyrds were more specific than that. Their records are filled with decisions that show how carefully they managed complexity.

One way to describe the band is to listen for what they don’t do. They rarely indulge in the kind of extended soloing that would satisfy a traditional jazz audience at the expense of the groove. They do not play funk as raw chaos; their funk is arranged, clean, and often luminous. Their melodies are not afterthoughts; they are structural beams.

“Walking in Rhythm” is a masterclass in this approach. Its writer, according to standard discographical notes, is guitarist Barney Perry, and its producer is Donald Byrd. The track’s success—Top 10 pop, significant adult-format traction—was not achieved by sanding off the musicianship, but by making the musicianship serve the song. The arrangement leaves space for the vocal, for the bass to be both anchor and dancer, and for the horns to speak in concise phrases rather than virtuoso monologues.

This was, in a sense, an answer to a broader industry question: could a band rooted in jazz education make records that worked on pop radio without becoming novelty or surrender? The charts suggested yes. A recent retrospective notes the song’s multi-chart climb and emphasizes how it moved across categories—soul, easy listening, pop—illustrating the breadth of its appeal.

But the deeper significance lies in how the band framed that crossover as normal. There is nothing defensive in the sound. The Blackbyrds do not sound like they are trying to prove they belong. They sound like they assume they do.

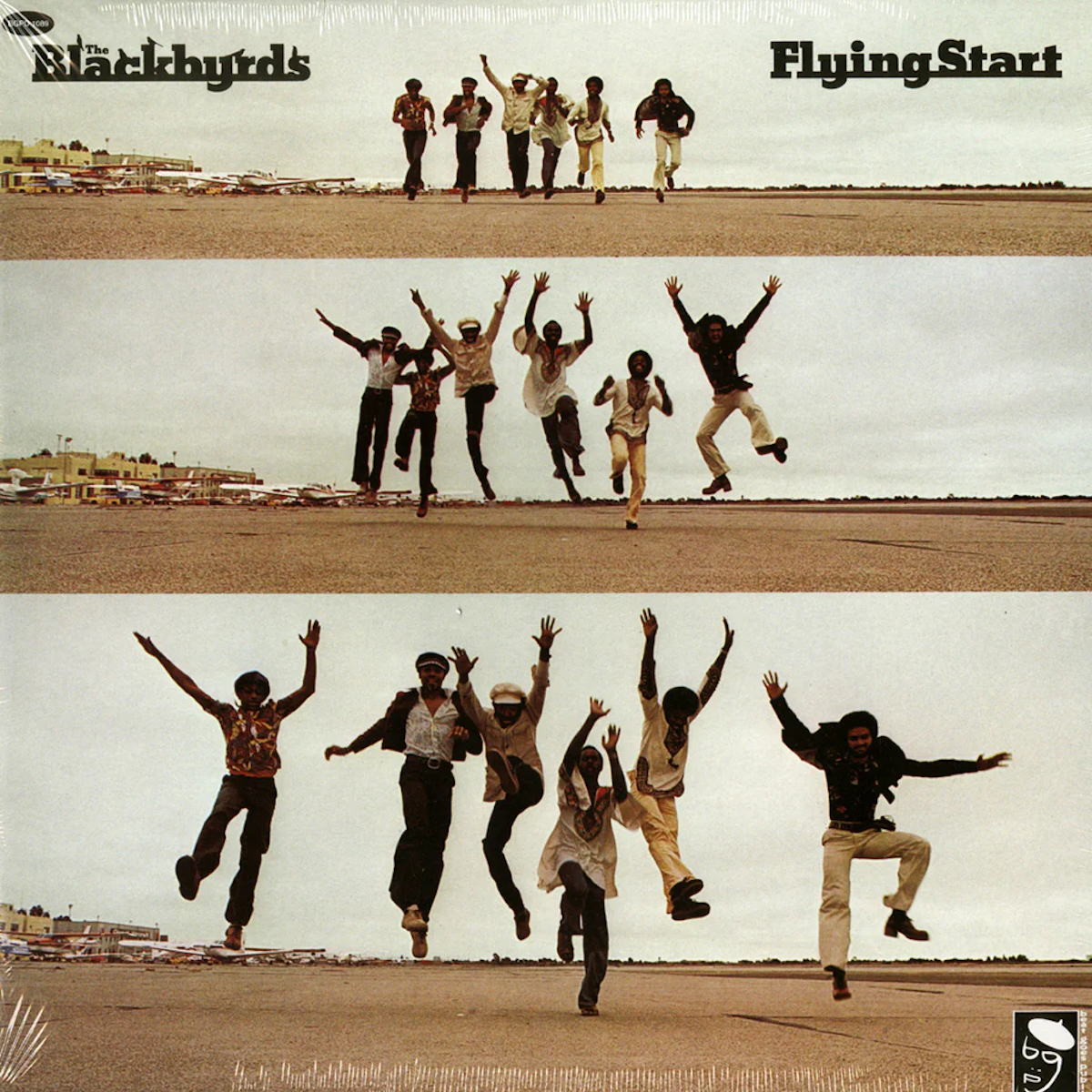

The early albums: A run built like a story arc

The Blackbyrds’ discography reads like a decade’s worth of negotiations between identity, marketplace, and growth. The band’s third album, “City Life,” is often treated as a pivot point, and the numbers support that. The album charted strongly across categories—jazz, R&B, pop—and achieved a Gold certification, as documented in standard chart and certification summaries. “City Life” is also the album that contains “Rock Creek Park” and “Happy Music,” tracks that function as both local anthem and dance-floor directive.

The Gold status of “City Life” is not just an industry plaque; it signals that an ensemble of young Black musicians—students turned professionals—could sell a sophisticated hybrid at scale. In the 1970s, that was not guaranteed. The record business was increasingly segmented by format, and “jazz” could be both a mark of prestige and a commercial trap. “City Life” slipped through that trap by sounding like the city it invoked: layered, kinetic, and full of movement.

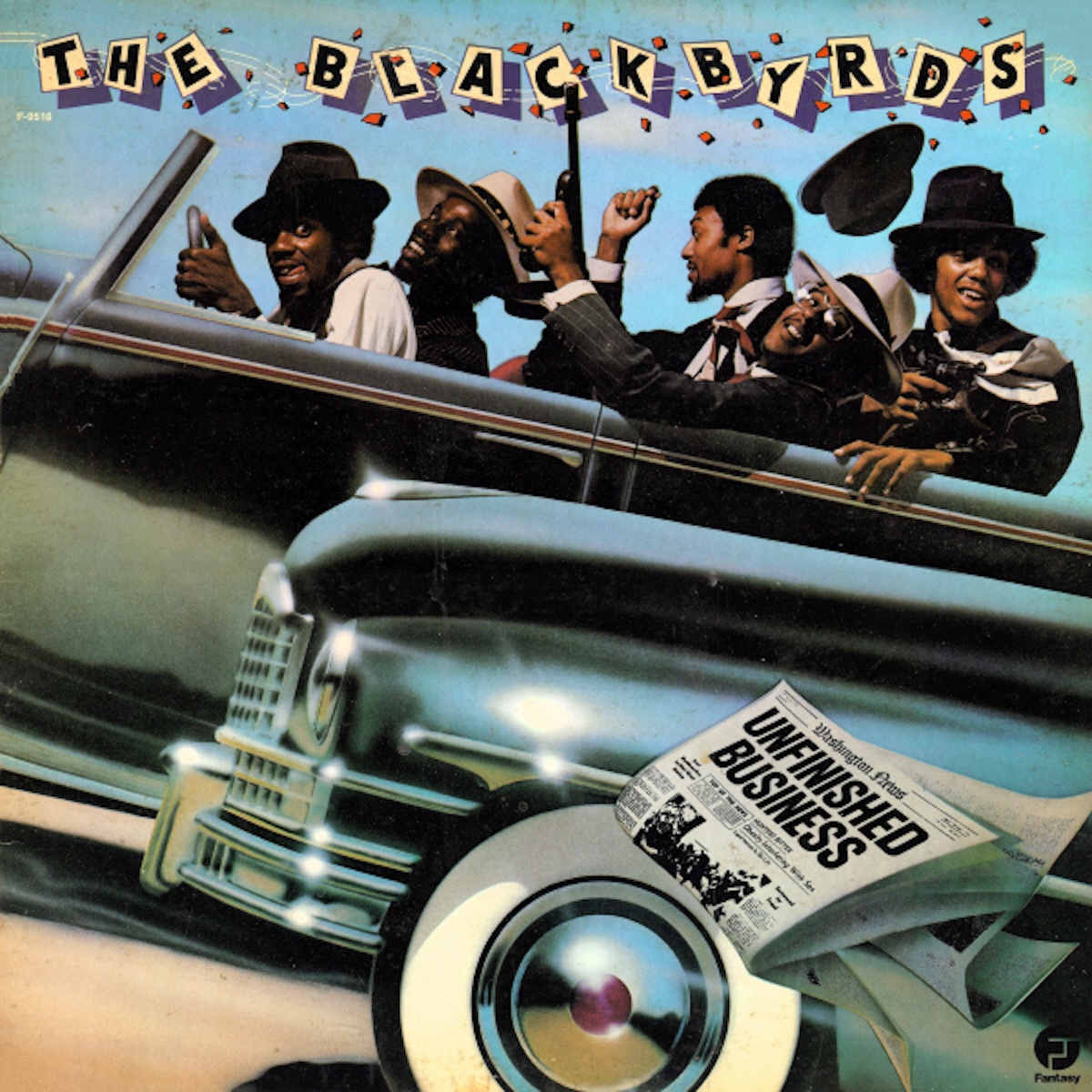

The following year’s “Unfinished Business” also achieved Gold certification and charted high on R&B and pop album rankings. Even the title reads like a statement: the band understood itself not as a one-off project but as a continuing proposition. Singles like “Time Is Movin’” and “Party Land” performed on R&B charts, indicating that the group could sustain momentum beyond the initial crossover miracle.

Meanwhile, coverage from The Washington Post during the era framed The Blackbyrds as Washington’s own nationally known jazz/R&B band and described the group’s trajectory as a kind of coming-of-age story—years of touring “behind Byrd’s jazz trumpet,” multiple albums produced by Byrd, and a sense that the group was ready to step out as an independent entity. That phrasing—ready to “fly the coop”—is telling. It acknowledges both the benefit and the constraint of mentorship. Byrd opened doors; Byrd also occupied the center.

The tension between mentor and band is not merely gossip; it is a structural theme in Black music history. Producers, label executives, and famous patrons have often served as gatekeepers. When the gatekeeper is also a genuine educator, the dynamic can become even more complicated: gratitude and obligation braided together.

Mentorship, control, and the question of artistic adulthood

The Blackbyrds were not the first band to navigate the “who owns the sound?” question, but their case is unusually clear because the group’s origin is explicitly tied to an educational mission. The mentor was also, for years, the producer. The group was both students and colleagues. That can create a fertile environment—rigor, access, guidance. It can also create friction: creative autonomy, economic equity, recognition.

Washington Post coverage from late 1978 describes the group after years of touring behind Byrd and multiple albums produced by him, suggesting they were preparing to strike out on their own. That moment—the desire to become a band in full, not a project—arrives in many ensembles’ lives. But for The Blackbyrds, it carried additional weight because the band’s very existence had been framed as part of Byrd’s “brainchild.”

It is tempting to narrate this as a simple break: father figure versus sons. Real life is usually messier. Byrd’s guidance helped the band develop a sound that could travel. He also, according to multiple biographies and label notes, produced their key records. Yet, a band that lasts cannot remain in apprenticeship forever. Artistic adulthood requires room to fail, to drift, to take risks that are not approved by the teacher.

The way The Blackbyrds navigated this reflects a larger Black cultural pattern. For Black musicians, institutional access has historically been limited, which means mentorship—formal or informal—can be both lifeline and leash. The success of a student ensemble can also become an argument about what the institution itself produces, which can lead to additional pressures: represent the school, represent the city, represent the genre, represent the benefactor. The Blackbyrds, by achieving commercial success, became representatives whether they asked for it or not.

“Pedestrian vocals” and the aesthetics of accessibility

One of the quirks of The Blackbyrds’ self-mythology is their embrace of what they call “pedestrian vocals,” a phrase attributed in the band’s biography to Keith Killgo’s father. The phrase can be read as self-deprecating humor, but it also captures an aesthetic choice. The Blackbyrds’ vocals—often communal, chant-like, unpretentious—are part of what makes their records feel welcoming. They do not aim for the gospel explosiveness of a soul revue or the virtuosic theatrics of a progressive rock act. They aim for something closer to what you would hear if the best musicians in your city decided to make the party feel inevitable.

This matters because a common critique of jazz-fusion projects is that they can feel like musicians playing at the audience: impressive, distant, cold. The Blackbyrds avoid that distance. Their singing is frequently more about vibe than narrative, more about invitation than confession. In “Rock Creek Park,” the lyrics are famously spare—so spare they become almost percussive, one more rhythmic layer. That minimalism is not laziness; it is a strategy for embodiment. You can join in after hearing it once. The groove becomes communal property.

In that sense, The Blackbyrds were quietly radical. They made music that assumed the audience was capable of sophistication but not obligated to labor. You could dance without decoding.

The hit that traveled: “Walking in Rhythm” as cultural artifact

“Walking in Rhythm” has aged in a particular way: it retains its sheen. It does not feel trapped in the 1970s in the way some funk records do, where the production choices mark them like bell-bottoms. Part of that longevity comes from arrangement discipline. Part comes from the song’s emotional focus: a forward-moving devotion, an insistence on getting back home, a mood of tenderness that does not collapse into sentimentality.

But the song’s cultural significance is also tied to what it represented in its moment. A band of young Black musicians—rooted in a historically Black university, guided by a jazz legend—had created a record that could thrive in mainstream radio. The crossover was not framed as a betrayal; it was framed as an expansion of what was possible.

The language of “crossover” itself is loaded. It often implies crossing a line from Black formats to white ones, from “urban” to “mainstream,” from the margins to the center. The Blackbyrds complicate that narrative because their music does not sound like it is assimilating. It sounds like it is bringing its own center with it. The horns still speak in jazz syntax. The rhythm section still respects funk’s body-first authority. The harmonic choices still reflect a trained ear. The “center” simply had to deal with it.

This is one reason the band continues to be referenced in contexts that go beyond nostalgia. They are not merely a “’70s band.” They are evidence that Black musical intelligence, when given resources and room, can invent new mainstreams rather than chase old ones.

“Rock Creek Park” and the afterlife of a groove

If “Walking in Rhythm” is the band’s most obvious pop monument, “Rock Creek Park” is their long tail—an asset that has traveled through decades, genres, and technologies. One measure of this is sampling culture. Standard biographies and retrospectives frequently note how often “Rock Creek Park” has been sampled or referenced, and contemporary reissue marketing explicitly calls it “heavily sampled,” positioning the track as a signature.

Sampling is sometimes discussed as a form of homage, sometimes as a form of extraction. In practice, it is often both. When hip-hop producers pull a loop from The Blackbyrds, they are pulling more than sound; they are pulling a mood of Black urban life that is both specific and malleable. The groove can become a backbone for different narratives—braggadocio, protest, memoir—without losing its underlying warmth.

The point is not to litigate every sample credit. The point is to understand how The Blackbyrds became part of hip-hop’s inheritance. In a sense, they were built to be sampled before sampling existed as a mainstream practice. Their records are cleanly recorded, rhythmically tight, melodically memorable, and arranged in sections that lend themselves to looping. That is not an accident; it is what happens when musicians are trained to think structurally.

A recent essay reflecting on “Rock Creek Park” argues that its continued sampling demonstrates the enduring relevance of the group’s themes of city life and Black agency, and frames the track as a kind of mapping of Washington’s cultural terrain. Even if one debates the essay’s emphasis, the larger point stands: the track has become a cultural resource, a reusable piece of Black musical infrastructure.

That is a different kind of significance than awards. It is significance as raw material for future art.

The Blackbyrds and the economics of “smooth”

There is a temptation to treat The Blackbyrds as purely joyous—happy music, sunny horns, park-after-dark flirtation. But embedded in their story is a hard economic reality. Jazz musicians in the 1970s were navigating shrinking mainstream attention and the rise of rock as a dominant commercial force. Fusion offered a route to relevance, but it also came with gatekeeping: labels wanted product, formats wanted categories, critics wanted purity, and audiences wanted pleasure.

The Guardian’s writing on Byrd frames his foray into funk and soul as commercially significant and sometimes artistically contested. The same dynamic shadows The Blackbyrds because their existence was part of Byrd’s response to the era. That does not mean the band was merely a commercial tool. It means they were created in a moment when commercial viability was itself a form of power.

What The Blackbyrds accomplished, then, was to turn “smooth” into something respectable on its own terms. “Smooth” is often used dismissively, as if accessibility is the enemy of depth. But in Black music history, accessibility has frequently been the means of survival and community building. A groove that welcomes the casual listener can also carry sophisticated musicianship underneath. The Blackbyrds specialized in that duality.

Their success also demonstrates the role of Black institutions—especially historically Black colleges and universities—in producing not only leaders and professionals but artists whose work enters the national bloodstream. That matters for cultural policy as much as for music criticism. When we talk about the arts ecosystem, we often focus on elite conservatories or major-city scenes. The Blackbyrds remind us that an HBCU classroom can be an incubator for innovation that reaches far beyond campus.

The long arc: Reunions, anniversaries, and local stewardship

By the early 1980s, the band’s first major era had cooled, and like many groups, they faced the realities of changing tastes, internal shifts, and industry churn. Yet the name did not disappear. A Washington Post piece from 1999 describes a moment when a venue wanted the Blackbyrds, only for the promoters to realize the band had not played a show in years; the article then recounts how Killgo contacted old members and rebuilt enough of the unit to perform, effectively reactivating the brand and the brotherhood. That story is less about nostalgia than about stewardship. The music remained valuable enough to summon the work of reunion.

Later community and festival descriptions continue to frame the band as a cutting-edge 1970s act whose boundary-pushing fusion still resonates, emphasizing their Washington roots and the guiding hand of Byrd at their founding. The 50th anniversary framing—“born at Howard,” still performing—signals that the group has become part of an institutional memory, not just a discography.

There is also a second-order impact: the members’ careers as educators and mentors. A profile published via Word In Black highlights Keith Killgo’s work teaching high school students about music careers and underscores how his experiences with The Blackbyrds inform his approach—an echo of the band’s origin story as education meeting industry. In other words, the band’s founding principle—bridge the gap—became a life practice.

This is how legacies become sustainable: not only through reissues and playlists, but through people who carry the ethic forward.

Why The Blackbyrds matter now

To write about The Blackbyrds in 2026 is to write about several intertwined histories at once: Black Washington’s cultural life, the evolution of jazz-funk and fusion, the economics of the 1970s record industry, the role of HBCUs in arts production, and hip-hop’s relationship to its sample-based ancestors.

The band’s significance is clearest when you resist the urge to file them under “classic grooves” and instead treat them as a model.

They are a model of how mentorship can be structured as opportunity rather than charity, even when that mentorship carries complex power dynamics. They are a model of how musical education can be used to make popular music that does not insult the audience. They are a model of how a band can become a place-maker—turning Rock Creek Park into an international sonic reference point. They are a model of how “crossover” can be reclaimed as a process of bringing your world into the mainstream rather than leaving your world behind. And they are a model of durability: the way a track recorded in the mid-1970s can become a component in music that did not exist yet.

Even the small details in archival and retrospective coverage reinforce this. When a Washington Post interview quotes Killgo describing the song’s origin—two grooves discovered backstage, lyrics arriving spontaneously, the feeling of the rhythm “made you feel the park”—you hear the band’s core skill: taking lived experience and turning it into a reusable musical design. When label and reissue material highlights “Rock Creek Park” as a signature and “City Life” as a chart-topping, gold-certified album, you see how industry validation followed the craft. When a 1978 Washington Post piece frames the group as ready to “fly the coop,” you see the human reality of musicians trying to own their trajectory.

And when contemporary festival and community write-ups still lead with the same essentials—formed in 1973, brought together by Donald Byrd, rooted in Washington—you see how origin stories harden into public memory because they contain a truth worth repeating.

The Blackbyrds’ greatest accomplishment may be that they created music that performs two functions at once. It documents a world—Black Washington in motion, students stepping into professional life, parks as nighttime sanctuaries—and it remains usable, in the most literal sense, by musicians and listeners who keep returning to it for pleasure, for samples, for atmosphere, for proof that sophistication and accessibility do not have to be enemies.

In a culture that cycles through trends at algorithmic speed, The Blackbyrds endure because they solved a perennial problem: how to make music that respects craft and still invites the room in. That invitation—open, rhythmic, confident—might be the most radical thing a band can offer.