Wilma Rudolph teaches that a life can be both extraordinary and constrained—and that the job of history is not to smooth away that tension, but to tell it cleanly.

Wilma Rudolph teaches that a life can be both extraordinary and constrained—and that the job of history is not to smooth away that tension, but to tell it cleanly.

By KOLUMN Magazine

The day Clarksville tried to be bigger than its rules

By the time Wilma Rudolph came home as the most famous American woman athlete on earth, the town that raised her was still living by the small architecture of segregation—separate doors, separate counters, separate assumptions about who deserved the center of the street. Rudolph had already been cast, by newspapers and broadcasters and admirers who preferred their heroes uncomplicated, as a miracle: the sickly child who could not walk, now the sprinter who could not be caught. But miracles do not return to ordinary places without forcing those places to answer for themselves.

In Clarksville, Tennessee, the celebration became legend for its own reason: the parade in her honor was staged without the town’s usual racial separation—an insistence, by Rudolph and her supporters, that if the city intended to celebrate her greatness, it would do so in a way that did not split her community in two. The details of that day, told and retold across decades, matter because they show what Rudolph’s speed had already done: it had made the world watch her. Now she was asking her hometown to see her.

This is the first thing to understand about Rudolph’s significance. She is not simply a story about athletic excellence. She is a story about how excellence, arriving in a Black woman’s body in mid-century America, collides with the nation’s habits—its romanticism, its condescension, its appetite for redemption narratives—and sometimes bends those habits, if only for a day, toward something fairer.

A child of abundance and illness

Rudolph was born in 1940 in St. Bethlehem, a community that would later be incorporated into Clarksville. She arrived as the twentieth of twenty-two children in a blended family—an upbringing that meant, in practice, a kind of dense mutuality: older siblings helping younger ones, resources stretched across many mouths, care distributed in a household where necessity made cooperation nonnegotiable.

Her early years were shaped not by track lanes but by sickness. Accounts of her childhood repeatedly note a succession of illnesses—pneumonia and scarlet fever among them—before polio, contracted as a young child, attacked her leg and threatened the basic independence of walking. In an era when medical access was sharply unequal and disability often became destiny, doctors’ prognoses could sound like verdicts. Rudolph’s family refused to accept one. What followed was not a single cinematic moment of triumph but years of care: massage, exercise, improvised therapy, persistence. The mythology sometimes compresses this period into a slogan—she overcame polio—but what it really describes is a network of people who believed she should have a future spacious enough to run inside.

By the time she was a preteen, she was walking without braces. Soon, she was moving fast enough that the story began to change genre. The child who had fought for mobility became the girl who had discovered flight.

The coach who built a dynasty—and the system that made it necessary

Rudolph’s ascent is inseparable from the institution that shaped her most decisively: Tennessee State University, and the powerhouse women’s track program known as the TSU Tigerbelles. In the mid-20th century, historically Black colleges and universities did something the broader sports establishment frequently would not: they invested, with seriousness, in Black athletes and in women athletes, often at the same time. The Tigerbelles became a factory of world-class sprinters and jumpers not because the world was generous, but because the world was not.

At the center stood Ed Temple, the program’s architect and disciplinarian, a coach whose legacy is often described in dynastic terms. He was not simply developing fast women; he was developing a model for how Black women could dominate a sport even when the rest of the country treated them as an afterthought.

Temple’s methods—tough, attentive, exacting—are part of the Tigerbelles lore. But so is his presence as a stabilizing adult figure in the lives of young women who were often navigating racism, sexism, and the intense scrutiny that came with being visibly excellent. The Guardian’s portrait of Temple’s era emphasizes not only his competitive genius but the way the program created sprint “queens” in a nation that did not easily crown Black women.

Rudolph enrolled at Tennessee State in 1957, already an Olympian-to-be, and quickly became the program’s brightest star. In that context, her greatness was not an accident. It was cultivated—by coaching, by competition, by a culture that normalized ambition for women who had been taught to expect less.

Melbourne: A teenager enters the world

Rudolph’s first Olympics came in 1956 in Melbourne, where she was still a teenager. She returned with a bronze medal in the 4×100 relay—already remarkable, but easy to overlook in the shadow of what came next. The relay matters, though, because it introduced Rudolph to the biggest stage while she was still learning her own range. It also framed her early international identity as both individual talent and team contributor—an athlete whose speed could anchor a collective outcome.

The narrative arc that later hardened around Rudolph—sickness to stardom—sometimes skips too quickly past Melbourne. But the Melbourne medal is proof that Rudolph was not solely a late-blooming miracle of Rome. She was, even at 16, elite.

Rome, 1960: A week that became a myth

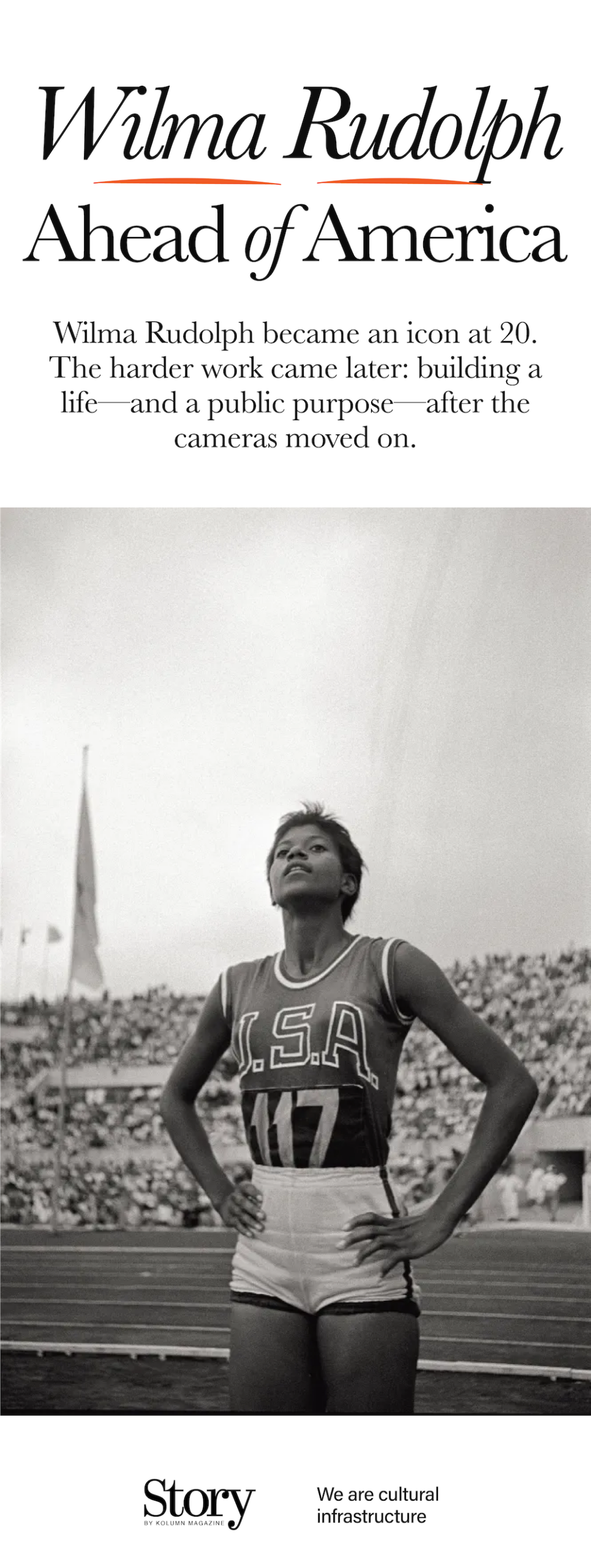

The Rome Olympics in 1960 were among the first to be carried widely by television, and the medium mattered. Track is a sport made for broadcast drama: clean lines, clear winners, time as an indisputable judge. In Rome, Rudolph delivered a spectacle that the camera could not improve because it was already perfect in its simplicity: she arrived in the lane, she exploded from the blocks, she separated from the field, she won.

She took gold in the 100 meters and the 200 meters, then anchored the 4×100 relay to another gold—three gold medals in a single Games. She became, as the U.S. Olympic & Paralympic Hall of Fame biography later summarized, the “Fastest Woman in the World” in the space of a week.

There is a detail that good storytelling sometimes fudges: Rudolph was the first American woman to win three Olympic gold medals in a single Games—not the first woman worldwide. The distinction matters not to diminish her feat but to keep the record honest. The Guardian itself published a correction years later clarifying that point, a small reminder that even celebratory sports writing can drift toward exaggeration when a story feels too satisfying.

Still, the core truth remains untouched: in Rome, Rudolph authored one of the defining athletic performances of the 20th century. A Guardian retrospective, written in the lead-up to another Olympics, captures the emotional logic of why it endures: the way Rudolph’s run reads as both personal vindication and universal metaphor, the idea that greatness can be hiding inside a body that the world once treated as broken.

Rome also made her an icon in Europe, where she was celebrated with a glamour that American society did not always extend to Black women. The international gaze, paradoxically, could feel less cramped than the domestic one.

The aesthetics of a Black woman champion

Rudolph’s fame in 1960 was not just about speed. It was about the way she looked while being fast.

This is an uncomfortable subject, but it is central to her historical role. Media accounts from the era often lingered on her beauty and femininity, as if to reassure audiences that a powerful female athlete could still be legible within conventional gender expectations. That framing carried its own trap. It attempted to domesticate her dominance—turning the fastest woman alive into a kind of acceptable celebrity, glamorous and smiling, rather than a figure who might disrupt deeper assumptions about race, gender, and power.

Rudolph navigated that attention with notable poise, but poise is not the same as freedom. When she became a star, she entered a marketplace where attention did not always translate into security. One widely repeated recollection attributed to her experience of the post-Rome celebrity circuit is that she was treated like royalty without being paid like it—praised, paraded, photographed, but not necessarily supported in a way that made her future stable.

In today’s sports economy—where a global sprint champion might leverage endorsements, appearance fees, and brand partnerships into generational wealth—it can be hard to remember how limited the infrastructure was for women athletes, especially Black women athletes, in Rudolph’s era. She was a world icon before the world had built a responsible way to compensate women for being icons.

The White House visit and the choreography of national pride

The United States, like most nations, has always enjoyed claiming champions as evidence of national virtue. Rudolph’s Rome triumph arrived during a period when American identity was being sold as a moral alternative to Soviet communism, and athletic success could be interpreted as ideological proof. Rudolph’s stardom thus became usable—an inspiring story of American possibility, suitable for ceremonies and invitations.

A White House Historical Association essay about Rudolph’s visit to the White House situates her within that tradition of national celebration, while also tracking how she moved through spaces that had not been designed with her in mind.

The choreography of such recognition is always double-edged. On one hand, it confirms achievement. On the other, it can flatten a person into a symbol. Rudolph’s life shows both dynamics in motion: she accepted public honors, and she also tried to use her platform to shape conditions back home, where symbolic inclusion did not automatically mean practical equality.

What it meant to insist on an integrated celebration

It is tempting to romanticize the integrated parade in Clarksville as a happy ending—proof that triumph can shame a community into decency. But the more rigorous interpretation is this: Rudolph understood that fame is leverage, and she chose to spend it on a principle.

For a Black woman in 1960 Tennessee, insisting on an integrated celebration was not an aesthetic preference. It was a political act. It forced local power structures to decide whether they wanted the prestige of honoring her more than they wanted the comfort of preserving segregation in public ritual. In that sense, Rudolph’s return home becomes part of the broader story of the Civil Rights era—not because she was a full-time activist in the conventional sense, but because she used her moment of maximum visibility to require a minimum of respect for her community.

This is a crucial correction to the standard “sports hero” template. Rudolph’s significance is not limited to what she did on the track; it extends to how she understood the track as a platform, and how she translated athletic capital into civic demand.

After the medals: The hard work of being a person again

Athletes who become icons young often face the same problem: they peak in public before they have finished growing in private. Rudolph retired from competitive track in the early 1960s, while still in her early twenties. The decision made sense—she had accomplished what few ever will—but it also meant she had to build a second life after the most famous chapter had ended.

A Tennessee State University library history of Rudolph and the Tigerbelles describes her later years with a tenderness that feels earned, noting her enduring connection to the program and to Ed Temple, even as illness later narrowed her world.

In the years after elite competition, Rudolph worked in education and community initiatives, and she remained a figure of inspiration—invited to speak, asked to appear, expected to embody resilience. Yet the burden of inspiration can be heavy, especially when public memory insists on the bright parts and neglects the complex ones: the financial uncertainty many athletes endured, the family responsibilities, the ways celebrity can complicate ordinary relationships.

Her story invites a broader question that American culture often avoids: what do we owe the people we turn into symbols?

Listening to her voice, not just her legend

For all the writing about Rudolph, one of the most valuable historical artifacts is simply hearing her talk about her life in her own words.

The American Archive of Public Broadcasting preserves raw footage from an interview conducted for a documentary called “Black Champions,” in which Rudolph discusses recovering from polio, playing basketball in high school, and transitioning into track at Tennessee State University, as well as her experiences at the 1956 and 1960 Olympics.

Interviews like this matter because they break the spell of the simplified narrative. They restore agency. They remind us that the “miracle” was not magic; it was work, memory, family, and the daily choice to persist.

They also show something else: Rudolph’s capacity to interpret her own story. She was not merely the subject of public meaning-making; she was a participant in it.

The Tigerbelles as cultural infrastructure

If you zoom out from Rudolph as an individual and look at the system around her, the Tigerbelles begin to resemble something larger than a sports program. They were a pipeline, an institution of belief—a place that treated Black women’s excellence as normal, not exceptional.

That is why the Tigerbelles story keeps returning in retrospectives about American sport. It is also why Rudolph’s legacy resonates beyond track. In an America that often debates what counts as “infrastructure,” the Tigerbelles are a reminder that cultural and institutional infrastructure can be just as decisive as physical structures. A track program, built with care, can change what becomes imaginable.

Rudolph’s significance, then, is partly architectural: she is proof of what happens when talent meets an environment that refuses to shrink it.

Death, grief, and the persistence of the symbol

Rudolph died in 1994 at age 54. Reporting at the time noted her death after a cancer diagnosis and emphasized both her continued involvement in sports-related initiatives and the depth of the loss felt by institutions that had long treated her as a living emblem of possibility.

A life that ends at 54 invites a particular kind of mourning. People do not only grieve the person; they grieve the imagined years that person should have had. With Rudolph, the grief was intensified by the narrative arc the public had assigned her: the girl who outran illness, the woman who outran history. Death feels, in that arc, like an interruption. But it is also a reminder that inspirational stories do not exempt anyone from the body’s vulnerabilities.

The Tennessee State account describes how, near the end, she still came to campus and walked with Ed Temple—a small, intimate image that counters the stadium-scale drama of Rome. It suggests what many athletes discover after the noise fades: the relationships matter as much as the records.

What she changed—and what she exposed

So what did Wilma Rudolph change?

She changed the record books, obviously. She changed the image of what an American champion could look like on television—Black, female, Southern, dazzling. She changed the way many young athletes, especially Black girls, understood the horizon of possibility. She helped make the case that women’s sprinting was not a sideshow but a main event. She made it harder for institutions to pretend that Black women’s excellence was rare.

But she also exposed the limits of celebratory narratives.

She exposed how quickly America will turn a Black woman into a symbol when she is useful, and how little structure exists to support her when usefulness fades. She exposed how media praise can carry conditions—that she be “feminine” in the right way, grateful in the right tone, triumphant without being too demanding. She exposed how the nation loves “overcoming” stories partly because they allow the nation to ignore the conditions that made overcoming necessary.

Rudolph’s life suggests that the most radical thing an athlete can do is not always to win. Sometimes it is to return home and insist that the celebration be honest.

The long afterlife of a sprint

Rudolph’s legacy continues to circulate through institutions and memory projects: halls of fame, museum exhibits, university archives, and youth education materials that keep her name in motion.

The Tennessee State University athletics site still frames her Rome performance as a defining moment in the school’s history. The Tennessee Historical Society–affiliated Tennessee Encyclopedia situates her not just as a champion but as a product of a particular place and era—a Black Tennessean whose achievements must be read alongside the state’s racial realities. The U.S. Olympic & Paralympic Hall of Fame biography crystallizes her achievements in the language of national sporting heritage.

Even the corrections—like the Guardian’s clarification about “first American woman” versus “first woman”—are part of that afterlife, because they show how her story is continually re-audited against the record.

In a way, that is the ultimate measure of her significance: the story stays alive enough to be argued with, refined, returned to. Icons who do not matter do not require maintenance. Rudolph does.

What her speed still teaches

Speed is often described as a gift. Rudolph’s life argues that speed is also a language.

On the track, her language was unmistakable: separation, control, inevitability. Off the track, the language became more complicated: navigating fame, insisting on dignity, translating personal triumph into communal meaning. If you reduce her to a single inspirational sentence, you miss the point. Her legacy is richer and more useful than inspiration.

Wilma Rudolph teaches that a life can be both extraordinary and constrained—and that the job of history is not to smooth away that tension, but to tell it cleanly. She teaches that greatness can emerge from scarcity, but also that scarcity is not romantic; it is a problem to be solved. She teaches that institutions like the Tigerbelles matter because talent alone is not a system. And she teaches that when a Black woman wins on the world’s biggest stage, the victory is never only hers. It becomes a referendum—on the country she represents, on the town that raised her, on the culture that watches her run and decides what, exactly, it is seeing.

Rudolph ran in an era that did not fully know what to do with her. The fact that we are still figuring it out is precisely why she remains essential.