It teaches that segregation did not merely restrict Black life; it also forced Black innovation in the form of institutions and spaces that created joy under constraint.

It teaches that segregation did not merely restrict Black life; it also forced Black innovation in the form of institutions and spaces that created joy under constraint.

By KOLUMN Magazine

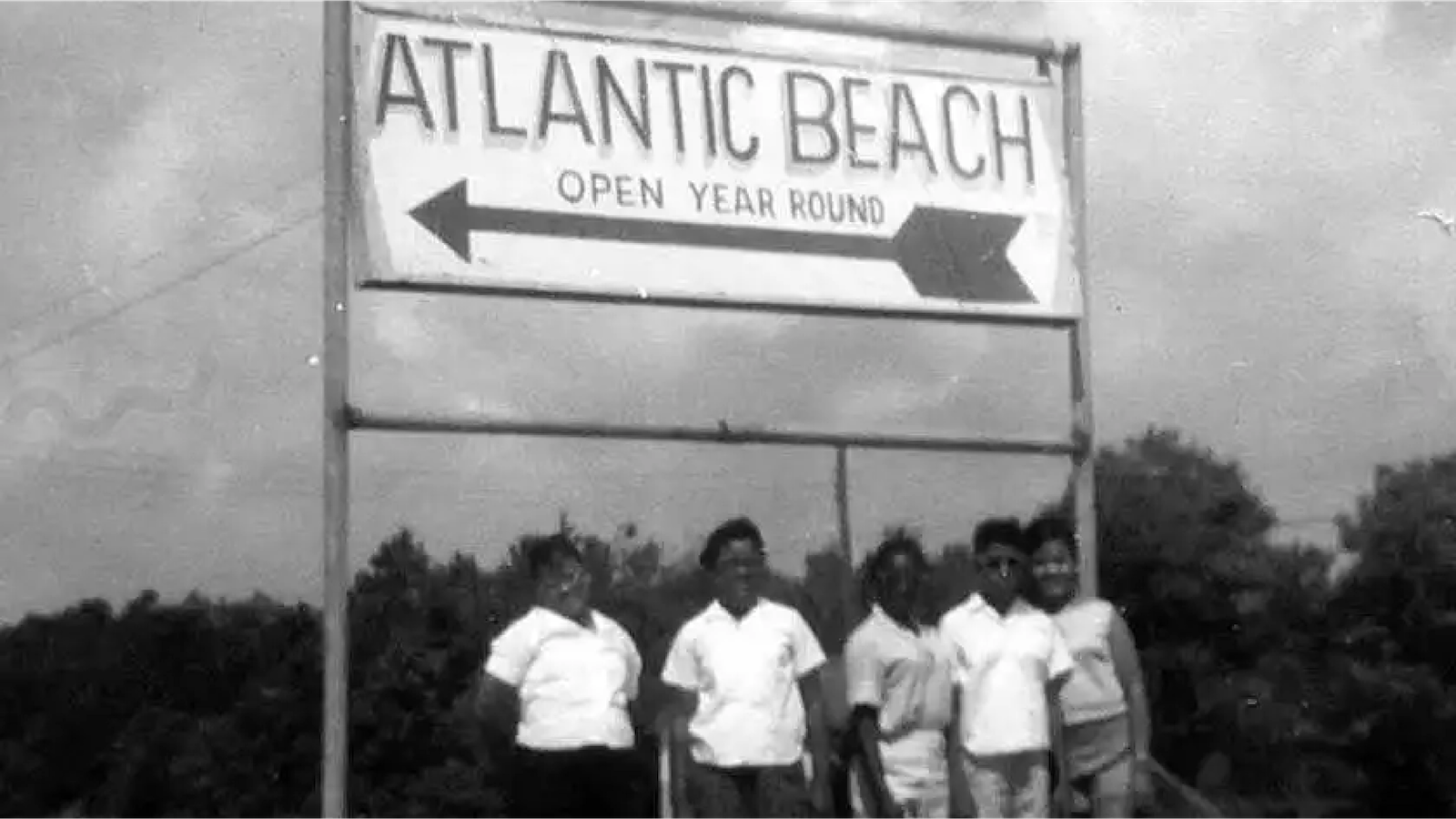

On the Grand Strand, where South Carolina’s coast has been engineered into one long invitation—condo towers, golf packages, neon seafood, and the kind of vacation abundance that feels permanent—there is a place that does not quite behave like the rest of the beach. Atlantic Beach is small enough to miss if you’re not looking for it. It’s also too consequential to treat as a curiosity.

From an aerial view, reporters have described it as a “cutout” of coastline—a small 92-acre municipality embedded inside the larger sweep of North Myrtle Beach, with the surrounding city wrapping around it in a way that makes Atlantic Beach look like a remnant of an earlier map. If you’ve ever driven Ocean Boulevard and wondered why the rhythm of the beachfront road breaks—why a familiar strand of pavement stops and starts again—that interruption tells you you’ve approached a seam in local history. In the South, seams are rarely accidental.

Atlantic Beach exists because, for much of the 20th century, the ocean itself was segregated. The coast was not merely land and water; it was access, it was dignity, it was who could rest without consequence. Atlantic Beach—nicknamed “The Black Pearl”—was created as an answer to that world: a Black-owned seaside retreat, built in the Jim Crow era so Black families could have something as ordinary, and as radical, as a summer at the shore.

It flourished for decades as a pocket economy of Black hotels, restaurants, bars, and nightclubs, a place where music and leisure made a kind of civic statement: we are here, we belong to the coast, too. Then it declined—buffeted by hurricanes, by the unintended consequences of desegregation, by regional tourism that scaled up and away from a small town’s capacity to compete. And now it faces a modern paradox: how to preserve a heritage born of exclusion without letting that heritage be flattened into branding—or priced out by the very real estate attention that comes for any remaining open piece of American coastline.

To write about Atlantic Beach is to write about the country’s relationship to Black space: the ways Black communities build refuge, the ways markets and politics test that refuge, and the ways memory must be defended not only against forgetting, but against “revitalization” that arrives with terms and conditions.

A refuge founded on purpose, not accident

Atlantic Beach’s founding story, like many Black community origin stories, begins with a mix of entrepreneurship and constraint. In 1934, a Black businessman named George W. Tyson purchased oceanfront land—47 acres—from a white landowner, R. V. Ward, paying $2,000 for property that would become the nucleus of Atlantic Beach. This wasn’t a sentimental purchase. It was an infrastructure decision. Segregation made leisure a problem to solve.

Tyson owned businesses serving the Black community in nearby Conway, and he understood something that is easy to overlook when we talk about travel during Jim Crow: movement required systems. To take a trip as a Black family in the segregated South wasn’t only to save money for gas and lodging; it was to calculate risk—where you could stop, where you could eat, where you could sleep without humiliation or danger.

So Tyson did what Black entrepreneurs have so often done in the face of closed doors: he built a door. He created a place, and he helped seed an economy around it. After the land purchase, he built the Black Hawk Night Club, a venue that became popular precisely because so many other venues were off-limits. He encouraged other Black buyers to purchase plots and develop them, leading to early sales and subsequent expansion—including the purchase of additional adjacent land.

In this early period, Atlantic Beach was not yet a town in the formal sense. It was a project—an oceanfront community assembled from parcels and aspiration. The National Trust for Historic Preservation has documented how these parcels were sold to Black buyers across a range of professions, from physicians to factory workers; sometimes people pooled resources to buy property together, a form of collective investment that reads like both necessity and strategy.

The cultural roots of many early residents were also tied to the Lowcountry’s distinctive African American heritage. The National Trust account notes that buyers included descendants of Gullah Geechee people, whose communities and traditions developed along the southeastern coast and Sea Islands under slavery and its aftermath. The Gullah Geechee Cultural Heritage Corridor—designated and supported through the National Park Service framework—exists to protect and interpret this coastal culture shaped by captive Africans and their descendants. While Atlantic Beach is not synonymous with the Sea Islands most commonly associated with Gullah Geechee culture, the corridor’s broader geographic and cultural logic—coastal Black communities preserving distinct traditions under pressure—helps explain why Atlantic Beach’s story resonates far beyond its size.

Atlantic Beach emerged, then, as part real estate, part sanctuary, part cultural stage.

The Black Pearl in its heyday

Every historic place has two histories: the one told in documents—incorporation dates, land transfers, zoning decisions—and the one told at family reunions, in remembered smells and sounds, in the body’s memory of freedom. Atlantic Beach has a particularly vivid second history, because the first history was shaped by a society that tried to deny Black people ordinary pleasures.

From the 1940s through the 1960s, Atlantic Beach entered what many residents and historians describe as its heyday: a thriving resort community where Black tourists came not only from nearby South Carolina towns but from across the country. The National Trust story, drawing on local oral history, describes a seasonal surge—April to October—when visitors fished, danced, gathered on open-air patios, and helped sustain a local business ecosystem.

That ecosystem mattered because it was an economy Black people could control. In white resort areas, Black labor often powered tourism—cleaning rooms, cooking food, maintaining grounds—without sharing in ownership or leisure. Atlantic Beach inverted that arrangement. It created a space where Black entrepreneurship could profit from Black joy, and where Black families could experience the coast without performing deference.

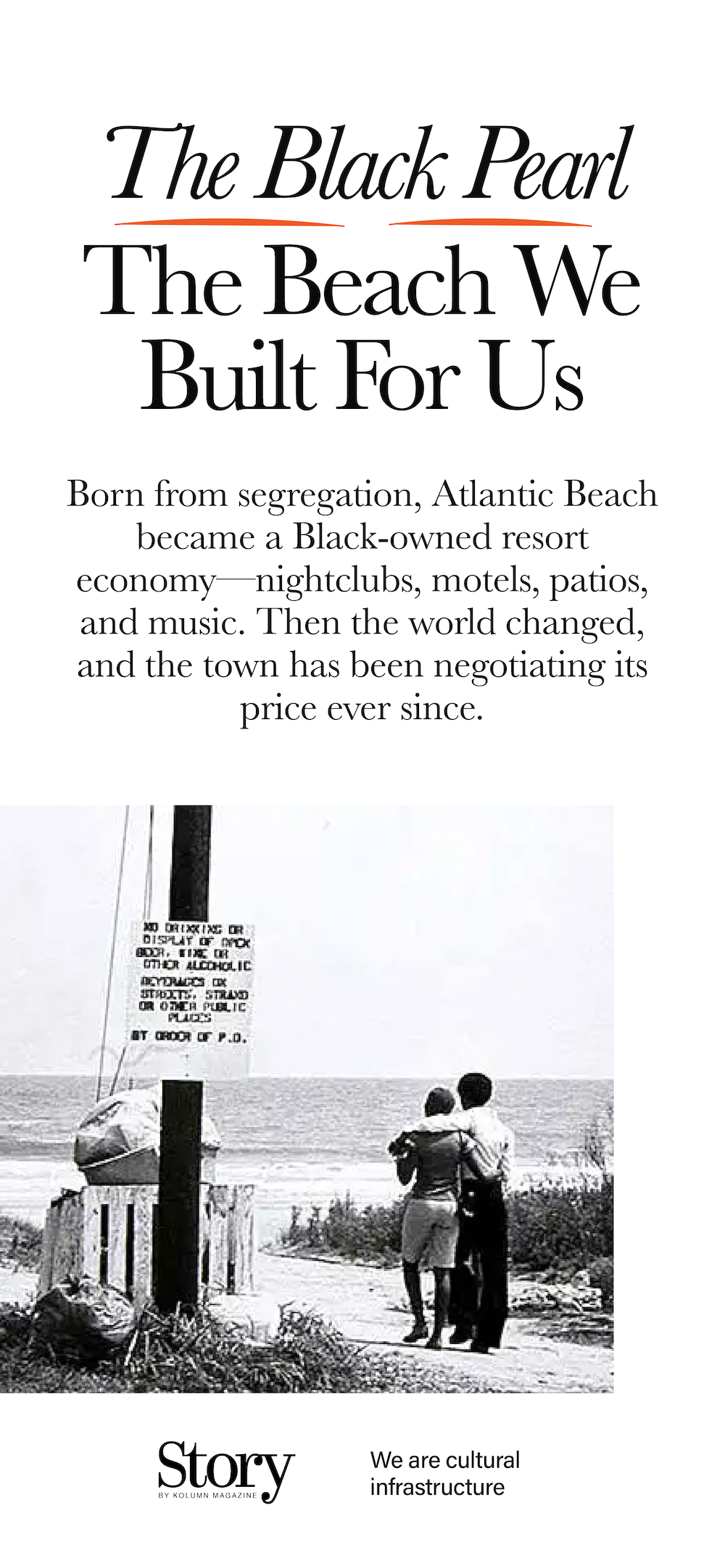

The Washington Post, in a 2023 feature, emphasizes how Atlantic Beach functioned as a “safe haven” when surrounding white beach towns enforced segregation through barriers like ropes and fences along the shoreline. That image—literal lines on a beach—captures the era’s brutality. It also underscores Atlantic Beach’s significance: not as a quaint “historic district,” but as a geographic exception to a racial regime.

If you want to understand why a four-block town can carry such weight, consider what it meant for a child to run into the Atlantic Ocean and not be told, in some direct or indirect way, that the water belonged to someone else.

Atlantic Beach also became a cultural node. The National Trust account notes that, because of segregation, the town hosted prominent R&B singers who performed nearby in Myrtle Beach. That detail suggests a familiar pattern in Black cultural history: artists navigating segregated circuits, performing in or near white venues while relying on Black spaces for lodging, community, safety, and after-hours life. The Black Pearl, in that sense, was both audience and backstage.

And then there were the storms—literal and political—that re-shaped the town.

Hurricane Hazel, desegregation, and the complicated cost of “access”

In 1954, Hurricane Hazel struck the Carolinas with devastating force, and the National Trust account describes how it leveled wood buildings erected in earlier decades. Hurricanes are part of coastal life, but for small communities they can be existential: the destruction is physical, and the rebuilding tests whether capital and patience still exist.

Some entrepreneurs rebuilt, and there were moments of renewed hope. Yet the larger shift came from something that, on paper, was progress. When civil rights gains and enforcement of anti-segregation laws in the 1960s and 1970s opened previously white-only beaches and venues, Black travelers gained access to more of the coast. That expansion of freedom is undeniable—and it is also true that it changed the economics of a place like Atlantic Beach.

The town’s own historical summary, posted by municipal sources, puts the point bluntly: desegregation “destroyed” parts of the community’s identity as the Black Pearl. That word—destroyed—is worth sitting with, not because desegregation was a mistake, but because freedom in America often comes with uneven market consequences. When Black travelers could go elsewhere, many did. The result was disinvestment in the very Black-owned spaces that had been built to compensate for exclusion.

This is the paradox of Black refuge spaces across the country: they are formed under constraint, then forced to compete under “open” conditions that do not automatically correct historical inequities in capital, marketing, infrastructure, or political power.

Atlantic Beach responded, in part, by formalizing itself.

Incorporation as self-defense

In 1966, Atlantic Beach incorporated as an independent municipality—a decision framed by local history as a choice to maintain its own governance rather than merge into the larger North Myrtle Beach area. The town’s history page notes that the original Atlantic Beach and Pearl Beach joined and incorporated on June 15, 1966, with Emery Gore as the first mayor.

Municipal incorporation is not glamorous, but for small communities—especially historically Black communities—it can be a form of protection. Zoning, policing, taxation, public works: these are the levers that shape who benefits from land and who gets displaced. By incorporating, Atlantic Beach asserted a right to make decisions about its own space.

But incorporation alone cannot solve broader regional dynamics. The Grand Strand tourism economy expanded dramatically over the late 20th century. Myrtle Beach and North Myrtle Beach grew into major destinations, with development patterns that favored scale, high-rise density, and brand-driven marketing. Against that machinery, Atlantic Beach’s intimate geography—four blocks, limited buildable land, a small municipal budget—was both its charm and its vulnerability.

Still, Atlantic Beach tried to create new engines of attention and revenue.

Bikefest, celebration, and the burdens of being a destination

In 1980, town officials initiated an event that would become one of Atlantic Beach’s most widely known cultural touchstones: Bikefest, tied to Memorial Day weekend and often associated with the broader phenomenon known as Black Bike Week. The National Trust notes Bike Fest as an effort to stimulate tourism and bring in revenue.

Over time, the event grew into a massive regional draw, often spilling beyond Atlantic Beach itself into the greater Myrtle Beach area. The Washington Post reported years earlier that the rally began with a small group and then ballooned in size, shaped in part by broader cultural currents and the shifting geography of Black leisure gatherings.

But big events bring complicated math. They can be lifelines for small towns and logistical nightmares at the same time. Traffic management, policing, vendor control, public safety, reputational risk—these pressures can overwhelm a municipality with limited resources. Bikefest, in other words, became part of Atlantic Beach’s identity and part of its challenge: a celebration that also forces the town to answer what it wants to be known for, and who benefits financially when crowds arrive.

Local and regional coverage in South Carolina has tracked the town’s continuing efforts to navigate Bikefest’s legacy while pursuing broader redevelopment and preservation strategies.

Preservation as a living practice, not a plaque

If the Black Pearl is to be more than a nickname, preservation has to operate as something more than signage. In the early 2000s, residents formed the Atlantic Beach Historical Society with a mission to preserve coastal African-American heritage through oral histories, memorabilia, and events. The National Trust account documents initiatives including the Gullah Geechee Festival and an oral history effort sometimes known as the “Colored Wall Oral History Project,” capturing residents’ memories of the town’s vibrant past.

That work matters because so much of Black coastal history is vulnerable—physically, to storms and rising insurance costs; economically, to speculative development; culturally, to the flattening of heritage into tourist-friendly shorthand.

More broadly along the South Carolina coast, news organizations have reported on how Black landownership—often rooted in heirs’ property passed down without formal wills—faces intense development pressure as coastal real estate values climb. These pressures aren’t unique to Atlantic Beach, but they shape how Atlantic Beach residents interpret any new proposal: not simply as “growth,” but as a test of whether the town’s founding purpose—Black access and Black control—will remain intact.

And then there is the national context of cultural preservation. The Gullah Geechee Cultural Heritage Corridor, supported through federal designation and interpretation, is one example of how preservation can be formalized. Recent reporting has also highlighted how Gullah Geechee communities face threats from climate change, development, and gentrification, even as institutions pursue grants and programs meant to support preservation. Atlantic Beach sits within that larger story of coastal Black communities trying to keep land, memory, and cultural practice from being treated as disposable.

The new fight: Development, height, and the meaning of “revitalization”

When a place has limited land, every proposal becomes existential.

In recent years, Atlantic Beach has faced contentious debates over development—particularly proposals that would change the town’s skyline and density, including high-rise plans. Local reporting has described town council actions to advance approvals for a controversial high-rise hotel, made possible by earlier amendments to land use. These debates, in turn, become arguments about what kind of future Atlantic Beach should have: a low-rise heritage enclave, a boutique cultural district, a modernized resort node, or some hybrid that tries to reconcile memory with market demand.

The Washington Post captured this tension in human terms, describing how condos and hotels in the surrounding area can overshadow what was once a self-contained haven, and how residents and officials debate how to preserve history while reinvigorating tourism.

In the language of city planning, this is the classic preservation-development conflict. In the language of Atlantic Beach’s history, it’s more personal: a community founded because Black people were denied access is now negotiating whether new access—new visitors, new investment—will bring empowerment or erasure.

That negotiation is happening amid broader political and developmental struggles reported by local South Carolina outlets, which describe persistent battles over governance and growth. For small towns, politics can be intimate: disagreements aren’t abstract; they are neighbors and family lines and property boundaries. For historically Black towns, those disagreements can also carry the added weight of historical distrust—who is at the table, who is profiting, who is being asked to compromise, and whose version of “progress” is being prioritized.

A place built for Black joy—and the problem of being remembered

One of the most haunting aspects of Atlantic Beach is that its decline is, in part, the result of the country getting “better” in a narrow legal sense. If you only measure progress by whether Black travelers can now go to any beach, Atlantic Beach can look like an artifact—an old solution to an old problem.

But that reading misunderstands what Atlantic Beach actually produced. It didn’t just provide access to sand and water. It provided proof of concept: that Black people could build, own, govern, and define a resort town on their own terms.

In that sense, Atlantic Beach belongs in the same national lineage as other historically Black leisure enclaves—places that grew during segregation because Black people were forced to create parallel infrastructure for rest and recreation. These places are often discussed as nostalgic footnotes. They should also be discussed as economic history: as examples of Black enterprise and Black spatial strategy.

A 2025 essay in Places Journal—written in a reflective, first-person mode—captures something that formal histories sometimes miss: the emotional texture of Atlantic Beach as a “refuge of sorts,” and the complicated relationship people have to nostalgia when the refuge existed because the outside world was violent. You can miss the sanctuary without missing the segregation that made the sanctuary necessary.

Atlantic Beach’s present-day challenge is that America is very good at consuming Black history as aesthetic while neglecting Black communities as living political entities. A “Black Pearl” can be marketed. A Black municipality—arguing about zoning, struggling with infrastructure costs, defending land tenure—is harder to romanticize, and easier to pressure.

What the Black Pearl teaches now

Atlantic Beach is small enough that you can walk it quickly. But you can’t “finish” it that way. Its meaning accumulates.

It teaches that segregation did not merely restrict Black life; it also forced Black innovation in the form of institutions and spaces that created joy under constraint. It teaches that legal rights, while essential, do not automatically preserve the Black-owned economies built to survive discrimination. It teaches that coastal land is a finite resource, and that in America, finite resources invite speculation—often at the expense of communities whose ownership is rooted in history rather than liquidity.

And it teaches a more uncomfortable truth: that preservation is not simply about saving buildings. It is about saving decision-making power—keeping enough control, locally, so that the story of the Black Pearl is not rewritten by outside interests with better lawyers, bigger budgets, and a smoother vocabulary for displacement.