An unofficial public archive of Jazz

An unofficial public archive of Jazz

By KOLUMN Magazine

The alley as a doorway

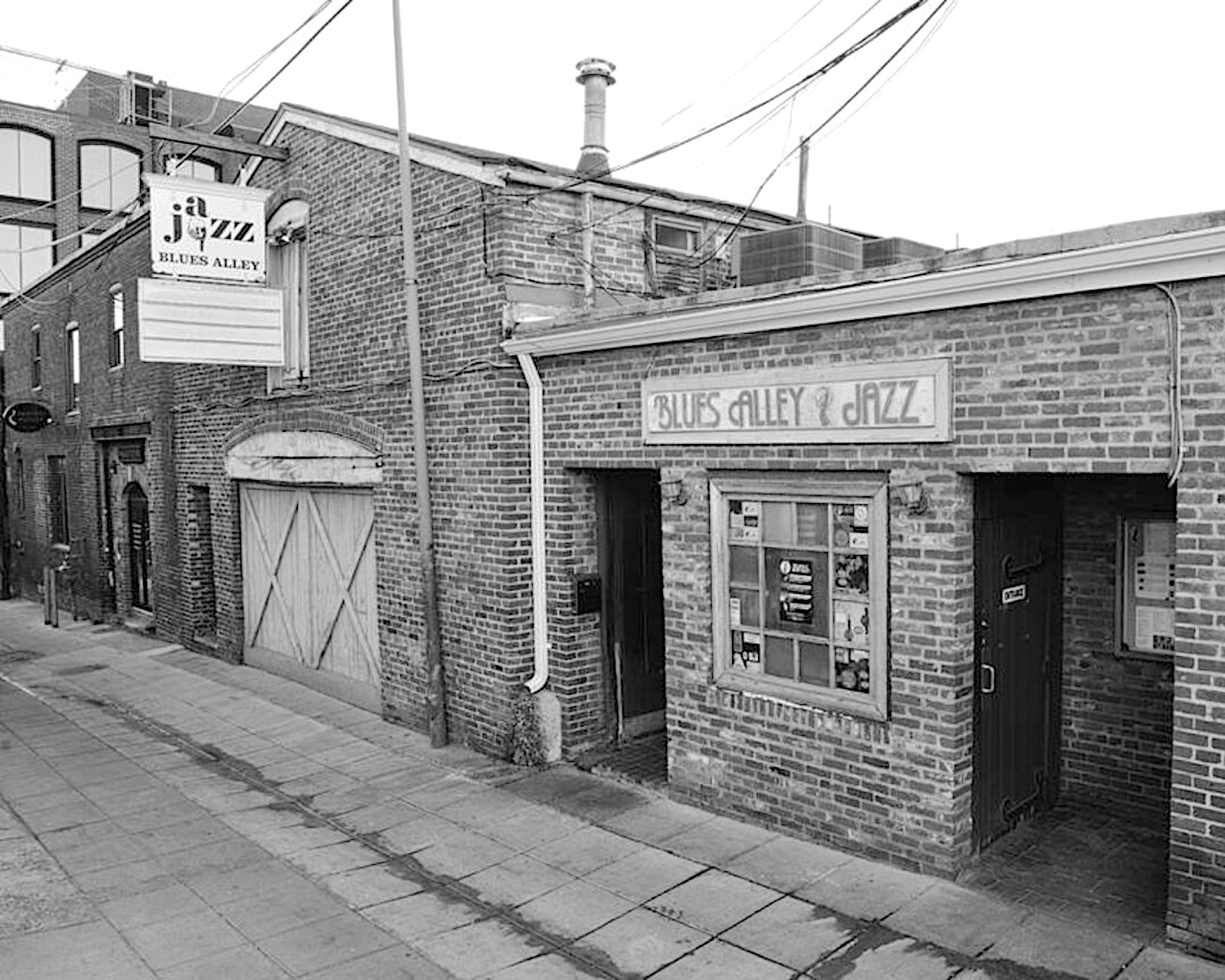

If you arrive the way most people do—late, hungry, slightly over-dressed—you may miss the place on purpose. That’s part of the design. The neighborhood above it sells visibility: bright retail windows, polished host stands, the choreography of Georgetown nightlife. The club itself sits back from the street, tucked into a rear carriage house. You step off Wisconsin Avenue and into a quieter corridor where the temperature seems to drop, the noise thins, and the city’s self-consciousness gives way to something older: brick, a small sign, a door that doesn’t try to persuade you. Inside, the room narrows and darkens as if the building is training your attention to fit the scale of what’s about to happen.

This is the basic technology of the jazz club—an architecture of focus. In the American imagination, jazz is often staged as spectacle: festival crowds, concert halls, gleaming institutions. But the art form’s native habitat has always been the room where the audience is close enough to hear the acoustic truth of a note: the breath behind the horn, the wooden click of a bass string returning to the fingerboard, the drummer’s soft argument with time. Blues Alley’s continued relevance rests on this intimacy. It is, by its own description, the nation’s “oldest continuing jazz supper club,” a distinction that is less brag than burden, because continuity has to be earned nightly.

To understand the significance of this club, you have to see it as more than a venue. It is a working cultural institution that has behaved, for decades, like an unofficial public archive. It has hosted the kind of artists whose names become shorthand for eras—legends who can fill theaters—and it has also served as a proving ground for emerging musicians who need a room that will hold them accountable. The club has been called “the house that Dizzy built,” a phrase that nods to the gravitational pull of Dizzy Gillespie and to a broader truth: in American music, certain rooms become reputations.

A Georgetown club with a D.C. story

It’s tempting to treat Blues Alley as a Georgetown curiosity—an elegant night out at the edge of a historic district. But its deeper story belongs to Washington. The city’s jazz lineage is not centered in Georgetown; it runs through a wider geography of Black cultural life that shaped the District in the 20th century. The historic U Street corridor—often remembered as “Black Broadway”—was one of the capital’s defining jazz zones from the 1920s through the 1940s, with venues like Bohemian Caverns serving as a gathering point for musicians and audiences during segregation and after.

Blues Alley arrived later, founded in 1965, at a hinge moment in American civic life. The mid-1960s were years of legislative breakthroughs and cultural pressure, of hope and backlash, of urban transformation that would only accelerate in the decades ahead. In Washington, jazz has long been entangled with the city’s identity—part entertainment, part social history, part commentary on who gets to belong where. That entanglement is visible in the way the city’s venues have opened, closed, moved, been redeveloped, been priced out, been reborn. Some, like Bohemian Caverns, became legends and then casualties of lease realities and neighborhood change.

Blues Alley’s significance is that it has endured through those cycles—through riots and redevelopment, through shifting tastes and industry collapse, through a pandemic that threatened live music’s basic business model. In that endurance is a particular lesson about the economics of cultural preservation: in America, art often survives not by being protected, but by being monetized just enough—night after night—to keep a door open.

1965: The founding and the form

The club’s origin story begins with a musician who wanted a room of his own. The venue was founded in 1965 by Tommy Gwaltney, described in multiple accounts as a traditional jazz clarinetist and vibraphonist who opened the space to celebrate the kind of jazz he loved and to play it regularly.

The “supper club” model mattered. A jazz supper club is not simply a bar with a stage; it is a hybrid institution whose revenue is structured around dinner service—food, tickets, and the promise of a full evening rather than a quick drink. That structure has always been both stabilizer and constraint. It stabilizes because it diversifies revenue. It constrains because it requires a specific kind of room-management: seatings, kitchen timing, audience turnover, the balance between dining conversation and listening culture.

Blues Alley’s physical plant reinforces that model. The club is housed, according to its own materials and multiple profiles, in an 18th-century red brick carriage house, an architectural detail that becomes more than ambience once you recognize what it implies: small rooms, low ceilings, irregular spaces, intimate distances. The building’s limitations are part of the club’s brand. When you hear that the venue is roughly 125 seats, you understand why artists often talk about the room as a test: there is nowhere to hide.

The club changed hands early in its life, and those transitions chart the difference between starting a room and sustaining it. By the late 1960s, Gwaltney sold the club to Bill Cannon, a retired Air Force colonel. Later owners included John Bunyan, and, eventually, Harry Schnipper, who has been central to the modern identity of the club and who purchased the building in 2021—an act that reads like real-estate strategy and cultural preservation at once.

Ownership matters because jazz clubs are fragile organisms. They depend on taste, tourism, local loyalty, and the availability of musicians willing to do the grind of multiple sets. They also depend on rent, which is often what kills them. The purchase of the building—rare in the club world—helps explain why Blues Alley could speak about survival with more leverage than many peers during the pandemic era.

“The house that Dizzy built” and the mythology of a room

Nicknames stick when they solve a problem: they compress complexity into something the public can remember. “The house that Dizzy built” does two things at once. It credits a star for the club’s aura, and it implies a particular kind of repertoire: jazz that treats history not as museum but as living language.

There is a promotional quote attributed to Gillespie on the club’s own materials—“Now THIS is a jazz club”—that speaks to the room’s self-understanding. When a venue places a legend’s voice into its marketing, it is doing what institutions do: borrowing authority. But the quote also sounds plausible because the club’s format aligns with the era in which Gillespie came up—rooms where you played multiple sets, where you entertained and experimented, where the audience learned how to listen as part of the night’s etiquette.

In practice, the club’s mythology has been built less by slogans than by repetition. Night after night, the same rituals: a front-of-house system that ushers people into tight seating; two sets; the subtle demand that diners treat music as more than background. Over decades, those repetitions form an identity powerful enough to become exportable. Accounts of the club’s influence mention international recognition, and the franchise attempts—such as a Tokyo outpost associated with Schnipper in the 1990s—suggest that “Blues Alley” became not just a place but a concept.

But the heart of the myth is local: the way Washington musicians and audiences have treated the room as a rite of passage. A landmark club does not simply host talent; it helps define what counts as talent in a city. And it provides continuity in a scene that is otherwise prone to fragmentation.

The house band era and the craft of backing greatness

One detail that often slips past casual fans is that many jazz clubs are as much about accompaniment as they are about headliners. Blues Alley’s history includes a house band tradition: the practice of maintaining a set of resident players who back up touring soloists. According to historical summaries of the venue, the club provided a house band beginning in the 1960s; lineups over time included musicians such as Gwaltney himself and players like Steve Jordan, Keter Betts, and John Eaton, with the house band discontinued in 1977.

In jazz, backing is an art and a discipline. A touring singer or instrumentalist might arrive with expectations and a book of arrangements, but the local band often has minimal rehearsal. They need to read charts, anticipate tempo preferences, follow cues, and recover gracefully from inevitable surprises. When a club maintains a reliable house rhythm section, it becomes more attractive to headliners. It also becomes a training ground for local players, who learn repertoire by doing it in public, in front of demanding audiences.

This is one reason a club can function like a conservatory without ever calling itself one. Young musicians learn how to support a vocalist, how to pace a set, how to handle a microphone, how to treat a gig as both craft and performance. When those musicians later become leaders themselves, the club’s influence persists as an invisible pedagogy.

Recording the room: When a venue becomes a label

If the club were only a room, it would still matter. But Blues Alley also became a recorder of performance—sometimes literally, through live albums that carry the club’s name into the world.

The phrase “Live at Blues Alley” appears on multiple albums across decades, turning the venue into a kind of brand for authenticity. One of the most widely known is Live at Blues Alley by Eva Cassidy, recorded at the club in January 1996 and released that year. The album became foundational to Cassidy’s posthumous rise, an example of how a local performance can become global legacy when the recording captures something irreducible—voice, vulnerability, a room’s attentive silence.

There are other “Live at Blues Alley” recordings tied to the venue as well, including releases connected to Wynton Marsalis and other artists, reinforcing the club’s role as a kind of acoustic signature.

Separately, discography listings and venue histories also reference recordings attributed to the club under its own banner, such as a “Live! At Blues Alley” association with Gillespie in the recorded marketplace. The precise lineage of each release varies by label and reissue history, but the larger point remains: the club’s name has been used as evidence. It tells listeners, “This wasn’t polished into existence; it happened in a room.”

That “room sound” has cultural meaning. In an era when jazz records could be assembled through overdubs and edits, the live album asserts a different value: risk. A supper club is not a laboratory; it is an arena where meals are served, glasses clink, and mistakes cannot be deleted. When a performance still lands—when a singer holds a ballad steady against ambient noise—that becomes part of the proof of artistry.

The Georgetown paradox: Prestige and displacement

Georgetown confers a particular kind of prestige. It is historic, wealthy, tourist-heavy, and, in the contemporary imagination, curated. A jazz club in Georgetown can benefit from that foot traffic and spending power. But Georgetown also carries the pressures that come with expensive neighborhoods: rising costs, strict expectations, the constant churn of retail and hospitality trends.

Blues Alley’s long tenure there highlights a paradox of cultural geography. Washington’s most celebrated Black cultural corridor is not Georgetown; it is U Street and adjacent neighborhoods where Black intellectual and artistic life flourished in the early 20th century. Yet one of the country’s most enduring jazz clubs sits in Georgetown, a neighborhood often read through a whiter and more affluent lens. The club’s history, then, becomes a story about how Black art circulates across spaces that have not always been built to center Black communities.

This is not to suggest the club lacks Black audiences or Black performers—quite the opposite. It has hosted an extraordinary range of artists, and recent coverage underscores its continuing efforts to feature emerging talent and to celebrate jazz’s lineage, including during Black History Month programming and anniversary events.

But the Georgetown setting shapes the club’s survival calculus. Tourism helps. High rents hurt. Neighborhood reputation can attract first-timers, while local loyalty keeps the calendar alive. In 2021, as the pandemic strained venues nationwide, reports described the club as searching for options tied to lease realities and survival strategy, a reminder that even iconic status does not eliminate structural vulnerability.

The pandemic years: Existential threat and the meaning of “reopening”

For live music venues, the pandemic was not merely a bad season; it was a direct attack on the basic premise of gathering. In jazz, where margins are already thin, the effect was devastating. A 125-seat supper club relies on bodies in chairs and food sold to those bodies. Remove the bodies and the business model collapses.

In early 2021, journalism about endangered jazz history framed the risk in cultural terms: the potential disappearance of rooms that carry intangible heritage, and the vulnerability of recordings and archives that often sit in private hands. Blues Alley appeared in this coverage as a symbol of what could be lost—an iconic site put under extreme pressure.

By September 2021, local reporting described the club’s return in language that carried both relief and defiance. The owner paraphrased Mark Twain—“rumors of our demise have been greatly exaggerated”—as the venue resumed shows in a limited schedule before broader national touring returned.

Reopening, in this context, is not a switch; it is a negotiation with risk, staffing realities, audience confidence, and the broader economy. Even after legal restrictions ease, the club has to rebuild habits: convincing people to sit close again, to buy dinner again, to treat live music as a normal part of life rather than an indulgence.

The pandemic also reclarified a hard truth about cultural institutions in America: many of them are privately owned businesses. They do not survive on public funding alone; they survive on nightly commerce. That makes them responsive to the market, but also vulnerable to shocks that have nothing to do with artistic quality.

Sixty years in: Celebration and a fight to survive

Anniversary celebrations can be sentimental—an excuse to run photos, quote famous names, and let nostalgia do the heavy lifting. But the club’s 60th year was reported not just as a party, but as a marker of ongoing struggle. Recent coverage described the anniversary week as a blend of legacy programming and economic anxiety: a room celebrating its history while facing higher costs and uncertain cultural funding landscapes.

That coverage also emphasized an aspect of Blues Alley’s significance that is easy to overlook: it helps “launch and revive” careers precisely because it offers a high-stakes, low-capacity stage. In a big theater, an artist can hide behind production. In a small club, an artist is exposed. That exposure can be career-making. It can also be career-recalibrating—a reminder of what an audience sounds like when they are close enough to be felt.

The anniversary programming referenced emerging talent alongside established artists, echoing a long-standing jazz ecology: the art form survives when stages are shared across generations, when young players can stand in the same room where the elders played. This continuity is part of what transforms a venue into a landmark. It becomes not just a place where famous people once performed, but a pipeline for the future.

The Blues Alley Jazz Society and the institutional turn

Landmark venues often evolve into something more institutional over time: festivals, competitions, nonprofit arms, educational initiatives. Recent reporting noted the presence of the Blues Alley Jazz Society as a nonprofit connected to investing in emerging artists, alongside anniversary references to events like competitions that bring new vocalists into the club’s orbit.

This institutional turn matters because it shifts the club’s identity from purely commercial enterprise to cultural stakeholder. It can create new funding pathways and new public value arguments: not just “come eat and listen,” but “support a pipeline of talent.” In an arts economy where philanthropy and public funding can be decisive, this kind of structure is also a survival strategy.

But it also creates a tension: jazz’s mythology thrives on the idea of the club as informal, spontaneous, ungoverned by bureaucracy. Institutionalization can protect, but it can also sanitize. The best version of this evolution is one where the nonprofit scaffolding supports the club’s rawness rather than replacing it.

What the room teaches: Listening as a civic practice

Jazz clubs teach audiences how to behave. That sounds moralistic, but it’s practical. Jazz is not always “easy listening.” It demands attention to shape and surprise. A supper club audience can be distracted by conversation, servers, menus. And yet, in the best nights, a room learns to quiet itself.

This is one of Blues Alley’s cultural contributions: it has kept alive a listening practice in a city where politics often dominates public attention. Washington is full of performance—press conferences, hearings, speeches, protests. Jazz is another kind of performance, one that insists on a different relationship to time. A solo unfolds; the audience waits; meaning is created not by message discipline but by risk.

In this sense, the club operates as a civic counter-space. It offers a setting where improvisation—not control—is the virtue. That matters in a capital city. It matters because it trains people, if only for an evening, to tolerate uncertainty and to find pleasure in it.

The wider D.C. jazz ecosystem: Survival through dispersion

Blues Alley’s endurance becomes clearer when you see it against the broader landscape of D.C. jazz. Over the years, the city’s scene has adapted through dispersion: multiple small rooms, pop-up series, festivals, universities, and cultural institutions sharing the burden of keeping jazz audible.

Local public media has pointed listeners toward a network of jazz joints and emphasized that, despite closures and challenges, the scene remains alive. In that network, Blues Alley is often framed as an anchor—long-running, recognizable, a destination for visitors and locals alike.

At the same time, the city’s jazz history is inseparable from the legacy of venues and corridors shaped by segregation. The U Street corridor’s history as Black Broadway, documented through cultural scholarship and public folklore work, reminds us that jazz in Washington was never just about entertainment; it was about community formation under constraint.

If Blues Alley is an anchor, it is not the whole ship. Its significance is partly symbolic: proof that a club can last. But the city’s jazz health depends on many rooms, including newer spaces and revived institutions. When a city loses venues, it loses more than nightlife; it loses the places where musicians develop in public.

A club as an archive of Black artistry

Any honest account of Blues Alley’s significance has to confront the racial realities of American music infrastructure. Jazz is a Black art form. Its global prestige has often been separated from the economic realities of Black musicians. The clubs and labels that profited from jazz have not always treated its creators equitably. A venue that celebrates jazz history, then, sits inside a larger American contradiction: Black genius as cultural treasure, Black labor as undercompensated work.

Blues Alley’s long list of performers—legends across eras—reflects the genre’s breadth and the club’s reputation as a must-play room. Summaries of the venue’s history and its own promotional materials name artists whose careers define American music: singers and instrumentalists whose presence in a 125-seat room collapses the distance between star and audience.

But the club’s deeper significance is not just that stars played there; it’s that the room helped translate jazz’s value to audiences who might otherwise treat it as background. In a city where Black culture is often consumed without being protected, the simple act of maintaining a dedicated jazz room is not trivial. It is a form of cultural stewardship, even when it is imperfect and market-driven.

The business of intimacy

A supper club is a business built on managing closeness. The tables are close, the sets are close, the margins are close. This creates a distinctive social atmosphere: strangers hear each other’s reactions, share the same narrow aisles, witness each other witnessing the music. The intimacy is not only musical; it is communal.

That intimacy also shapes the artist’s labor. Two sets a night, 60 minutes each, repeated across multiple nights—this is the rhythm of club jazz described in recent coverage. The format demands stamina and craft. It rewards artists who can build a narrative arc within an hour, who can adjust to audience energy, who can find variety across sets without losing coherence.

For audiences, the intimacy can feel like access. For artists, it can feel like accountability. That dynamic is one reason the club continues to attract performers: it offers a direct feedback loop, the kind that is increasingly rare in a music industry mediated by streaming metrics and social algorithms.

The fight for the next decade

In 2025, the club’s 60th anniversary coverage made clear that survival is not a solved problem. Economic headwinds—rising costs, uncertainty in arts ecosystems, shifts in tourism and nightlife patterns—still threaten small venues.

The club’s ability to endure will likely hinge on the same factors that have carried it through past crises: adaptability in booking, a balance of legacy acts and emerging talent, and the continued willingness of audiences to treat live jazz as worth leaving the house for.

There is also the question of what “significance” means in a city and a country that often only recognizes culture once it is endangered. The pandemic years made this painfully clear: Americans mourned venues at the moment they were closing, then moved on. The more difficult task is to value them while they are still open, still imperfect, still demanding.

Blues Alley’s story suggests that preservation is not always a plaque or a grant. Sometimes it is a Tuesday night with a modest crowd, a working band, and a room that still expects people to listen.

What it means that the door is still there

The most telling detail about Blues Alley is not the famous names—though there are many—nor even the age. It is the insistence on continuity. Founded in 1965, still presenting shows, still describing itself as a supper club, still leveraging an intimate room in a historic carriage house as the core of its identity.

In a country where cultural memory is often outsourced—to streaming platforms, to anniversary documentaries, to museum exhibitions that arrive after the fact—there is something radical about a place that makes history in the present tense. You don’t have to read about what happened there. You can sit down, order dinner, and watch a musician risk something in real time.

That is the club’s significance: it is an argument that jazz is not a chapter. It is an ongoing practice. And in a narrow alley behind Georgetown’s commerce, that practice still has a home.