Toussaint's ethic: Give in ways that are effective, repeatable, and close to the ground. Not once, but always

Toussaint's ethic: Give in ways that are effective, repeatable, and close to the ground. Not once, but always

By KOLUMN Magazine

If you want to understand Pierre Toussaint, resist the temptation to begin with sainthood.

Begin instead with work—its indignities and its possibilities. Begin with the quiet, exacting labor that made him legible to the powerful, and the quieter labor still that made him indispensable to the vulnerable. Toussaint’s story has been told so often in the language of sanctity that it can flatten into stained glass: the saintly former slave, the pious immigrant, the benefactor of the poor. Those are not untrue frames. The Catholic Church has formally recognized his “heroic virtue,” declaring him “Venerable,” a major step on the road to canonization. But the religious arc, on its own, can obscure the more demanding truth: Pierre Toussaint lived in a world where Blackness was criminalized socially and constrained legally; where slavery’s logic persisted even in “free” states; where a person could be indispensable and still disposable. His moral imagination formed inside that contradiction.

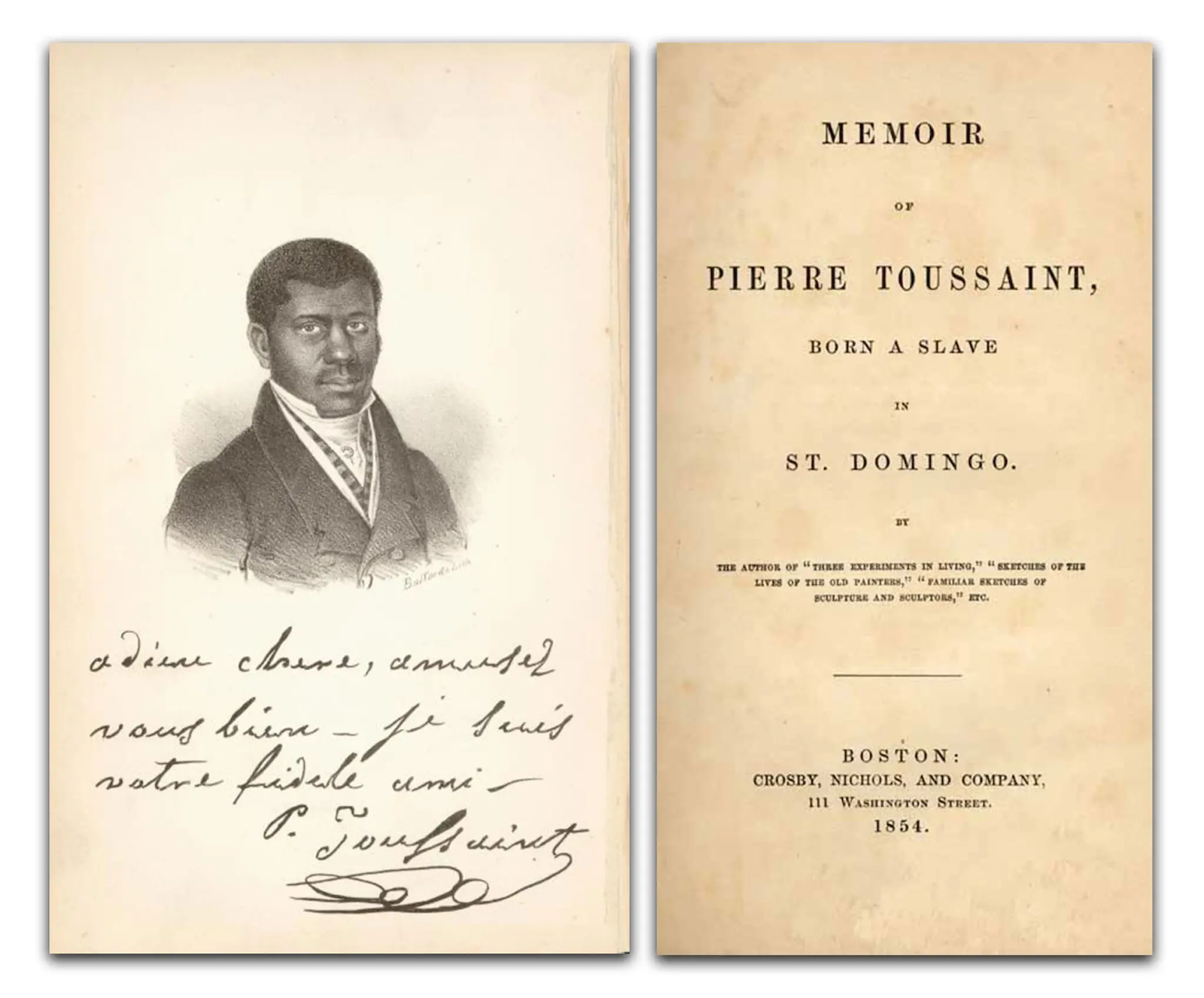

He was born in 1766 in Saint-Domingue—today Haiti—then France’s brutally profitable colony, a place where sugar wealth was extracted by coerced Black labor and secured by violence. Toussaint entered life as property in a society that turned human beings into balance-sheet entries. The details of his childhood are necessarily filtered through later recollections and early biographies, some written by white admirers who saw in him a model of Christian virtue and social order. The archival record, as with so many enslaved people, is uneven. Yet the broad outline is consistent across accounts: he was enslaved in Saint-Domingue, brought to New York City in 1787 by his enslavers, and apprenticed in the trade that would make him both visible and, in a narrow sense, powerful—a hairdresser serving the city’s elite.

The year matters. 1787 is a talismanic date in American civics: the Constitutional Convention, the machinery of a new republic. The same year, an enslaved Haitian teenager arrived in New York—an immigrant carried not by choice but by ownership. That coincidence has been noted in later commentary precisely because it exposes the republic’s doubleness: ideals of liberty built alongside the management of unfreedom.

New York, too, is often misremembered. It would eventually cast itself as a northern city of commerce, immigrants, and abolitionist righteousness. In the late eighteenth century, it was also a city where slavery was ordinary and profitable; where households purchased and hired out enslaved labor; where Black people—free and enslaved—moved under suspicion and surveillance. Toussaint’s life unfolded in that ambiguous space, where the economy depended on Black labor while the social order insisted Black people remain subordinate.

What made Pierre Toussaint unusual was not that he escaped those forces. He didn’t. It was that he learned to operate inside them with a precision that confounded the categories meant to contain him.

The apprenticeship: Scissors, salons, and social intelligence

Hairdressing in early New York was not merely grooming. It was intimacy, theater, and information. Elite women’s coiffures required time, skill, and trust; hairdressers moved through drawing rooms and bedrooms, heard the gossip of merchants and politicians, and learned the rhythms of status. When Toussaint became known as a premier hairdresser, he entered a rare occupational channel where a Black man—enslaved, then free—could earn significant income and cultivate relationships with wealthy households. Several accounts emphasize that he was “highly sought-after,” a reputation that in itself signals something startling: in a racially stratified city, his labor became fashionable.

But Toussaint’s visibility came with constraints. In many slave systems, skilled enslaved laborers were allowed to earn “tips” or wages beyond what was demanded by their enslavers—money that could sometimes be saved, sometimes confiscated, sometimes leveraged for survival. In Toussaint’s case, later narratives describe him using money he received through hairdressing to assist others—most notably to buy freedom for family members, including his sister. Even in those accounts, a key fact persists: his income flowed through a system that still claimed his body.

There is a moment in the Toussaint legend—repeated because it so perfectly dramatizes virtue under pressure—where he is said to have chosen to remain enslaved longer than necessary because he believed it would help him care for the widowed woman who “owned” him. Some retellings emphasize this as an act of Christian charity: he stayed to support a household that was collapsing, eventually becoming its primary breadwinner. Read sympathetically, it is a story of moral agency: a man refusing to let bitterness dictate his choices. Read skeptically, it is also a story of structural coercion: a Black man so entangled in a system that even his generosity is recruited to stabilize it. Both readings can be true at once, and any serious telling of Toussaint must hold that discomfort.

What’s less ambiguous is the pattern: by the time he was free—accounts commonly place his emancipation in the early nineteenth century, after the death of his enslaver—Toussaint had already developed a practice of distributing resources quietly and consistently. Charity, for him, was not an episodic virtue. It was a budget line.

A Haitian in New York: Revolution’s aftershocks

Toussaint’s migration from Saint-Domingue to New York cannot be separated from the Haitian Revolution’s long shadow. Saint-Domingue in the late 1780s and 1790s was a place in upheaval—enslaved people fighting for freedom, colonial powers scrambling, refugees fleeing. New York became one destination for displaced French and Haitian households and for free people of color navigating a new Atlantic world. Later Catholic and historical sources note that Toussaint, now in New York, encountered Haitian refugees bringing news of “murder and devastation” from the island—and that he responded materially, using his earnings to assist those in need.

Here again, the point is not merely that he was kind. It is that he understood displacement as a permanent condition of Black life in the Atlantic world—a condition that demanded infrastructure. Before modern social services, refugee aid was ad hoc: a room offered, a job arranged, a child placed with a family, a burial paid for. Toussaint worked in precisely that register. His charity reads less like philanthropy-as-brand and more like mutual aid stabilized by personal discipline.

A Washington Post report from 1990, written as the Church pursued evidence for his canonization cause, captures the peculiar collision of science, faith, and history: anthropologists digging for his remains near Old St. Patrick’s Cathedral as part of the investigative process around sainthood. That detail—bones sought in the earth, holiness pursued through documentation—suggests how Toussaint’s life has been continuously reinterpreted, repurposed, and verified. Even his body became an archive.

The Catholic layman and the city’s moral economy

Toussaint’s Catholicism is not incidental; it is the language through which he organized his obligations. He is frequently described as “devout,” and his modern cause for canonization is explicitly tied to a life understood as spiritually exemplary. But the more interesting question is what Catholicism offered a formerly enslaved Haitian man in early New York.

In part, it offered community. In part, a moral framework. But it also offered a transnational identity that complicated America’s racial caste system. Catholic New York was itself a minority culture in a Protestant-dominant nation; it was an immigrant church, often distrusted by elites. Toussaint’s position inside that church—particularly his association with St. Patrick’s—placed him at the intersection of multiple hierarchies: racial hierarchy within the city, class hierarchy within Catholic congregations, and ecclesial hierarchy that rarely centered Black laypeople.

And yet, he became central.

Multiple sources credit him with supporting Catholic charitable works and helping finance the construction of Old St. Patrick’s Cathedral in lower Manhattan. In a religious institution where wealth historically translated to influence, a Black hairdresser’s financial support carried both symbolism and leverage. It signaled that Catholic New York’s built environment—its stone and mortar—was partly funded by someone whom the wider society would prefer to keep invisible.

It is hard to overstate what a cathedral represents in a nineteenth-century immigrant city. It is not just a church; it is legitimacy made physical. To contribute to it is to claim a stake in the city’s moral architecture. Toussaint, whose origins marked him as foreign and enslaved, insisted—through his giving—that he belonged to the city’s future.

Marriage, domestic life, and the discipline of care

Toussaint’s life story often includes his marriage to Juliette Noel (sometimes spelled in variants), herself associated with experiences of enslavement and migration. Accounts note that they were buried together and later moved together to the crypt of St. Patrick’s Cathedral.

That detail can read like hagiographic romance, but it also points to the domestic and logistical labor that undergirded his public charity. Care is rarely a solo endeavor. If Toussaint’s home became a node in a network of aid—taking in orphans, housing the poor, supporting those in crisis—then marriage and household management mattered. The saint story tends to center individual virtue; the social history story asks who cooked, who cleaned, who nursed, who kept accounts, who made the home a functional refuge.

The record, again, is incomplete, and responsible reporting should name that limitation. Still, even the broad contours suggest that Toussaint’s philanthropy was not the distant giving of a benefactor. It was proximate. He gave not only money but space and time.

The paradox of proximity: Serving elites, serving the poor

Toussaint’s life is a study in proximity. He spent his days in the homes of the wealthy, tending to appearances, listening, learning. He spent his money and nights tending to the poor, the sick, the newly arrived. This dual proximity is the engine of his historical significance. It is also where many of his challenges lived.

Because to serve elites is to witness how wealth protects itself—how need is hidden, how suffering is aestheticized, how charity can function as a performance. Toussaint would have observed, intimately, the ways New York’s upper classes narrated themselves: their piety, their propriety, their fears. He would also have observed their contradictions: support for a church that preached universal dignity while tolerating racial hierarchy; compassion that extended only as far as social comfort.

His response was not public denunciation. It was redistribution.

Some will read that as accommodation. Others will read it as strategy. In the language of later admirers, he was “empty of resentments,” a phrase that appears in a Washington Post opinion piece reflecting on Haitian contributions to America and invoking Toussaint as emblematic of generosity. But the “no resentments” framing can be a trap; it can romanticize Black forgiveness as a requirement for recognition. The more challenging interpretation is that Toussaint’s restraint was not emotional emptiness but disciplined focus. He understood that rage, however justified, does not automatically feed an orphan. He chose to convert proximity to wealth into a kind of welfare system.

That conversion required navigating racism without letting it dictate the terms of his humanity. It required mastering an etiquette that was not designed for him. It required patience in a city where Black ambition could be punished as insolence.

A philanthropic practice before “philanthropy” had institutions

Modern readers often think of charity as institutional: nonprofits, foundations, donor-advised funds, annual reports. Toussaint lived in a time when much of social welfare was relational and church-based. Catholic charitable works in New York would eventually become formalized, and multiple sources claim Toussaint is credited as a foundational figure—some even calling him a de facto founder of Catholic charitable activity in the city.

Whether or not one accepts every superlative, the logic is clear: he was doing the work of social services before the city or church had robust systems for it. He supported orphanages, aided the poor, and directed resources to those excluded from mainstream help.

To call him “philanthropist” can mislead, because it implies surplus wealth and leisure. Toussaint’s wealth came from labor—labor performed in a racial order that often treated Black excellence as a novelty at best and a threat at worst. His giving was not a hobby; it was a second occupation. It demanded constant triage: who needed rent, who needed medicine, who needed food, who needed a burial. It demanded discretion in a society that might punish a Black man for appearing too influential. It demanded faith not just in God but in the fragile trust networks that made mutual aid possible.

The afterlife of his reputation: “Our Saint Pierre” and the making of a symbol

During his lifetime, accounts suggest that some people already referred to him as “our Saint Pierre.” That phrase is revealing. It implies familiarity and possession—saintliness as something a community claims for itself. It also implies that Toussaint’s reputation functioned as a moral argument within New York: evidence that holiness could emerge from a Black layman, from an immigrant, from someone the broader society ranked low.

But reputations are shaped by the needs of those who tell them. For Catholic New York, Toussaint offered a counter-narrative to anti-Catholic and racist assumptions. For Black Catholics, he offered representation in a communion that has often marginalized them. For white admirers, he offered a comforting story of Black virtue that did not threaten the social order—charity without rebellion. Each constituency could “use” Toussaint.

A journalist’s task is not to strip away all symbolic meaning—symbols matter—but to show how the symbol was made and what it costs. If Toussaint becomes only a “good” former slave, he risks being drafted into the very moral economy that made slavery palatable: the idea that the oppressed prove their worthiness through extraordinary virtue. Yet his life can also be read as an indictment: if it takes near-superhuman discipline for an enslaved person to become safe in public memory, what does that say about the society doing the remembering?

Death, burial, and a place where laypeople rarely go

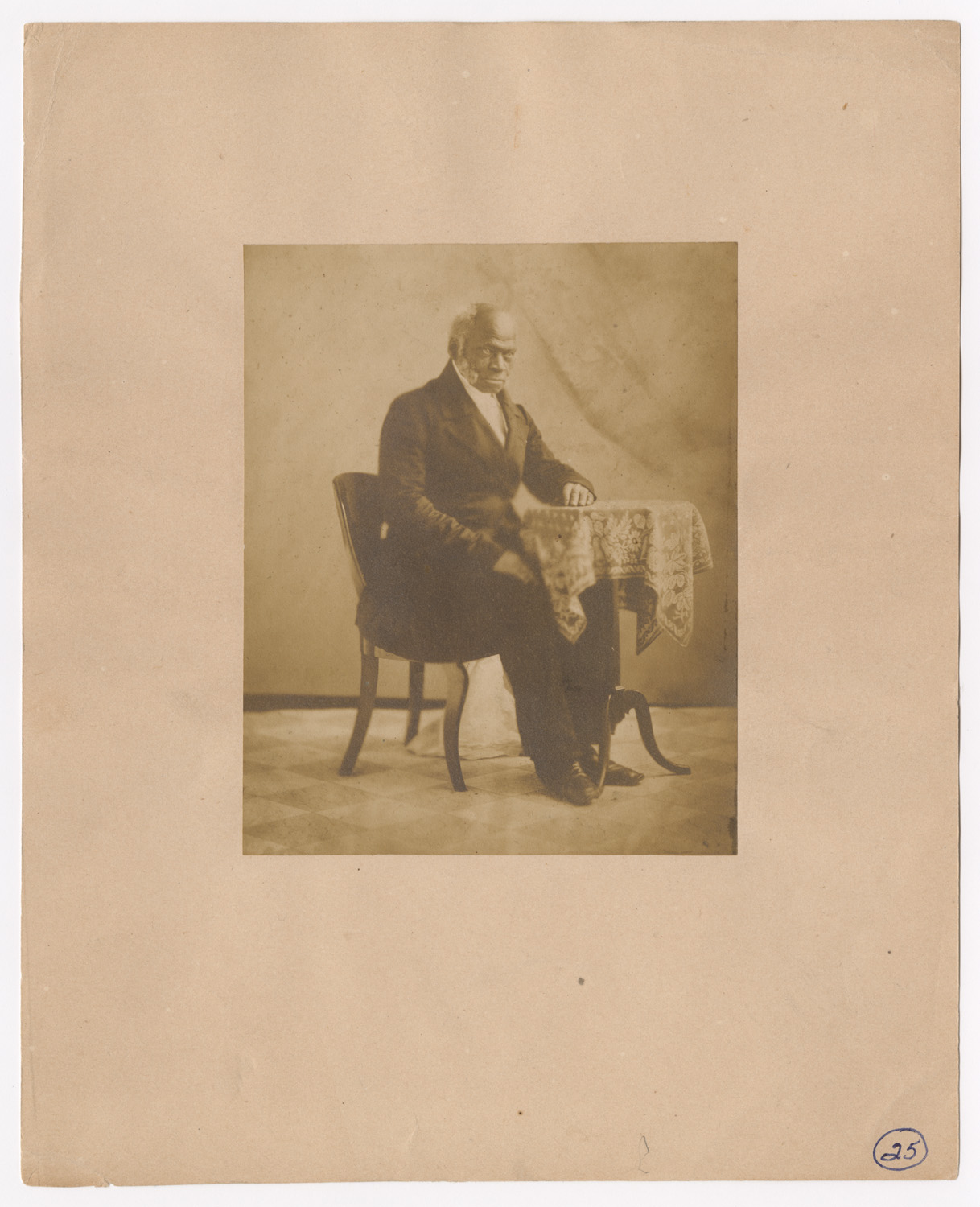

Toussaint died in New York City in 1853. The bare fact of his death is less interesting than what followed: his burial and reburial became part of his legacy.

Multiple sources note that he is the only layperson buried in the crypt of St. Patrick’s Cathedral on Fifth Avenue, beneath the main altar—an extraordinary honor in Catholic practice, generally reserved for clergy and bishops. He and his wife’s remains, originally associated with Old St. Patrick’s, were later transferred to the newer cathedral’s crypt.

Burial is politics. Where a person is placed in death reflects where institutions decide they belong. To place Toussaint beneath the altar is to make a statement about whose holiness can undergird the church—literally supporting it from below. It is also a statement about New York’s memory: the city that once treated him as property eventually enshrined him at its Catholic center.

Still, honor does not erase history. Toussaint’s burial location can be read as reconciliation, but it can also be read as a challenge: a reminder that the church, like the city, benefited from systems that degraded the people it now venerates.

Loremipsum

Lorem ipsum dolor sit amet, consectetur adipiscing elit, sed do eiusmod tempor incididunt ut labore et dolore magna aliqua.

The canonization cause: Verification, miracles, and modern longing

The Catholic process of making saints is often misunderstood as simple proclamation. It is, in fact, an investigation—part theological, part historical, part bureaucratic. Toussaint’s cause for canonization opened in the late twentieth century and culminated in his recognition as “Venerable” in 1996 by Pope John Paul II, according to several sources. (Some reporting places the declaration in the mid-to-late 1990s and ties it to the Church’s broader consideration of Black American candidates for sainthood.)

To move from “Venerable” to “Blessed” (beatification), Catholic tradition typically requires a verified miracle attributed to the candidate’s intercession, and another miracle for canonization. A Washington Post piece from 2000, discussing Black candidates for sainthood, lays out that basic structure while positioning Toussaint as a leading figure in that field. Another Washington Post story from 2000 describes a family praying for healing after reading about Toussaint—an example of how devotion forms in the space between story and need.

This is not merely ecclesial procedure; it is cultural longing. In an American church and nation wrestling with race, immigration, and historical violence, Toussaint becomes a figure through whom people ask: What would it mean for a formerly enslaved Black immigrant layman to be named a saint? Whose lives are legible as holy? Who gets to represent American Catholicism?

Contemporary writing about the Vatican’s “saint-making process” has used Toussaint as an anchor, precisely because his cause is longstanding and because it intersects with a renewed movement among Black Catholics advocating for multiple Black American candidates. The renewed attention is partly devotional, partly political: sainthood is a form of institutional recognition that can shift whose stories are told in parishes, schools, and national narratives.

Why Pierre Toussaint still matters now

Toussaint’s life sits at the intersection of the themes that continue to define American debate: race, immigration, labor, faith, and the moral responsibilities of wealth.

He matters to New York because he embodies an older, less romantic city: a city built not only by famous tycoons and immigrant strivers but by enslaved labor and Black skill; a city where a hairdresser could quietly finance a cathedral and an informal safety net.

He matters to American Catholicism because he challenges the assumption that holiness arrives primarily through clergy or through dramatic martyrdom. Toussaint’s claim is that lay life—work, marriage, budgeting, caregiving—can be a site of sanctity. He also challenges the racial imagination of the church by centering a Black immigrant not as a peripheral figure but as foundational, even to the church’s material infrastructure.

He matters to Black history because his story complicates the standard binaries: North versus South, slave versus free, rebellion versus accommodation. Toussaint’s resistance was not armed revolt. It was sustained, strategic care—a redistribution that quietly undermined the idea that the poor deserve their poverty.

And he matters to anyone trying to understand philanthropy as more than branding. In a moment when charity is often narrated through billionaire pledges and high-visibility campaigns, Toussaint offers a different ethic: give in ways that are effective, repeatable, and close to the ground. Not once, but always.

A closing image: Beneath the altar, above the city

There is a scene that almost writes itself: Toussaint’s remains beneath the altar of St. Patrick’s Cathedral, the city’s noise above—taxis, tourists, commerce, spectacle. The symbolism is tidy, almost too tidy: the humble man elevated, the enslaved man honored.

But the more honest image is messier and, therefore, more instructive.

Imagine him walking the streets of early New York after finishing work—hands smelling faintly of pomade, pockets holding coins that were never truly his until they were. Imagine him pausing at a tenement door, passing money to someone who could not repay. Imagine him returning home to a household where care was practiced as routine. Imagine him rising the next morning to do it again.

Sainthood is often defined by miracles. Toussaint’s miracle, if you strip the story down to its human mechanics, was stamina: the ability to keep choosing other people in a society structured to deny his own humanity. That is not a miracle that suspends the laws of nature. It is a miracle that exposes the laws of society—and how one person, armed with skill and discipline and faith, can bend them toward mercy.