KOLUMN Magazine

She understood that the vote is not merely a right; it is the visible edge of a deeper capacity: to interpret the world, to navigate institutions, to demand services, to persuade neighbors, to sustain collective action after the cameras leave.

She understood that the vote is not merely a right; it is the visible edge of a deeper capacity: to interpret the world, to navigate institutions, to demand services, to persuade neighbors, to sustain collective action after the cameras leave.

By KOLUMN Magazine

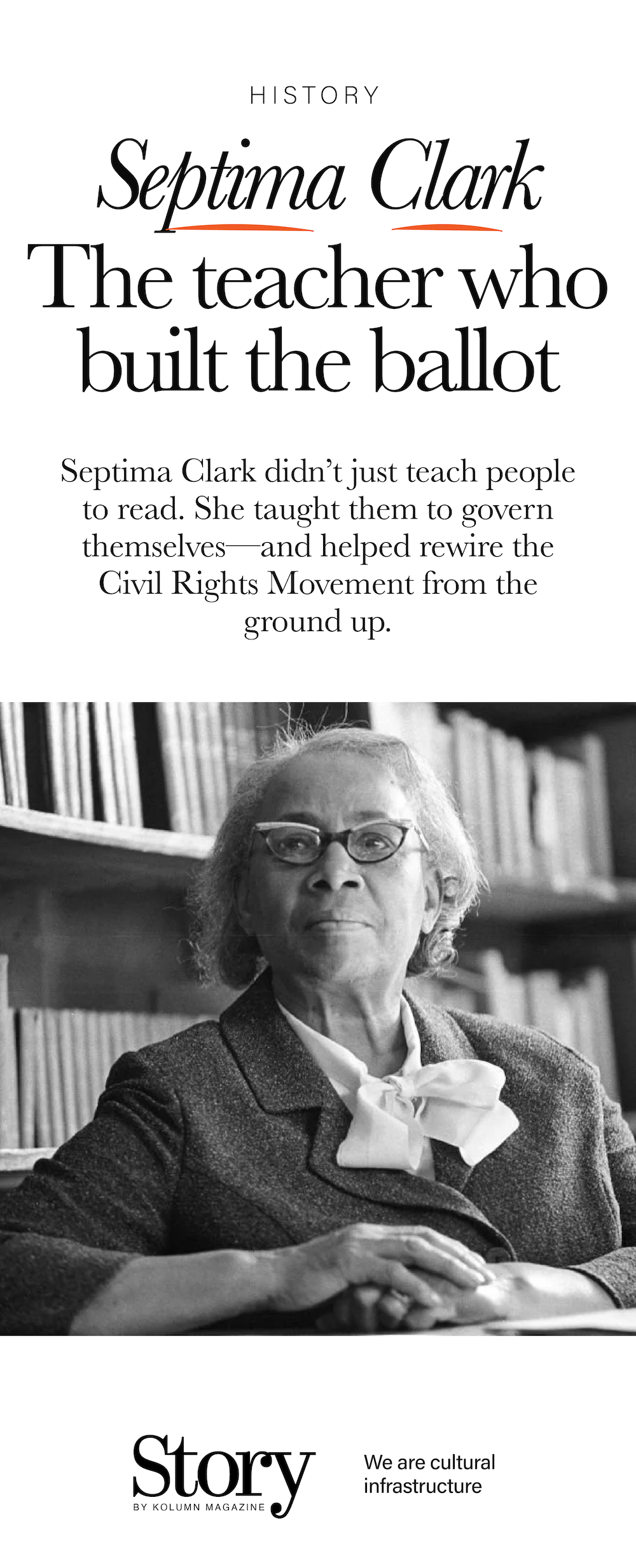

Septima Poinsette Clark lived long enough to watch the Civil Rights Movement become a national myth—flattened into a few names, a few marches, a few climactic speeches. She also lived long enough to see, at least in fragments, the country begin to acknowledge what the movement’s insiders had always known: that its power came not only from charisma at the microphone, but from infrastructure—patient, local, improvisational work that trained ordinary people to act like citizens in a system built to keep them from the ballot. Clark’s name is often offered now as an honorific, a correction, a belated gesture: “Mother of the Movement,” Martin Luther King Jr. called her, praising her “expert direction” of the Citizenship Education Program that became, in his words, a “bulwark” of the Southern Christian Leadership Conference’s program work.

But the title can mislead if it becomes merely sentimental. Clark’s story is less about being a symbolic matriarch than about building a replicable technology of democracy. In the mid-1950s and into the 1960s, she helped engineer a model of political education that merged literacy training with civic practice—teaching adults to read, to write, to fill out forms, to understand local government, to interpret the obstacles placed in front of them, and to organize with their neighbors anyway. The Citizenship Schools—taught in kitchens, beauty parlors, church basements, and wherever safety and discretion could be negotiated—became the movement’s quiet engine, producing the confidence and competence that allowed mass registration drives, local political leagues, and durable grassroots leadership to take root.

Clark’s life also clarifies a harder truth: the movement’s internal hierarchies often mirrored the country’s. Women—especially Black women who did not fit the era’s public-facing leadership archetype—were indispensable and frequently undervalued. Clark understood this with particular acuity, because she had been both celebrated and constrained: widely respected for her teaching genius, often sidelined as a decision-maker; heralded as essential to voter education, yet expected to accept diminished visibility. She did not romanticize the work. “Don’t ever think that everything went right,” she warned, acknowledging failure as a companion to strategy.

To tell Septima Clark’s story well is to treat it as more than biography. It is an instruction manual in how democratic power is built when formal institutions are hostile—and how a teacher, rooted in the realities of segregated classrooms, can become one of the most consequential political organizers of the twentieth century.

Charleston beginnings: A childhood shaped by constraint, and by insistence

Septima Poinsette Clark was born on May 3, 1898, in Charleston, South Carolina, into a world where Black possibility was constantly negotiated against white control. She was the daughter of a mother who worked as a laundress and a father who had been born into slavery. The family’s circumstances were not unique for the time, but Clark’s memories of childhood are precise about what deprivation felt like in institutional form: overcrowded classrooms; minimal instruction; the sense that the system was designed not to cultivate, but to contain.

In an oral history interview years later, Clark described her earliest public-school experience in Charleston with an almost cinematic clarity: children seated on bleachers in what she called an “ABC gallery,” so many packed together that the teacher’s main task seemed to be marching them to the bathroom and back before dismissal. Her mother, Victoria Warren Anderson Poinsette, responded as many Black parents did when the state failed their children—by finding alternatives. Clark was pulled from that public school and sent to a small home-based school run by an older woman, where she learned to read and write through strict discipline and close attention.

Even here, the story refuses sentimentality. The home school was effective, but harsh, and the methods reflected an era when education was both a pathway and a battleground. What mattered was outcome: literacy as protection, literacy as mobility, literacy as a form of dignity.

Clark’s family history also carried the complexities of the Atlantic world into a Charleston neighborhood. In her oral history, she spoke of her mother’s connections to Haiti and of an upbringing shaped by layered identities and migrations. These details are not incidental; they hint at a worldview that was never purely local. Clark would become an organizer deeply rooted in Southern communities, but her understanding of citizenship—what it should mean, and what it did mean under Jim Crow—was always expansive, tested against broader ideas of human rights and democratic promise.

The making of a teacher—and an early lesson in the politics of employment

Clark graduated from secondary school in 1916 and passed the teacher’s exam, beginning her career on Johns Island outside Charleston, teaching in a Black school at a time when Charleston restricted Black teachers’ access to city public-school jobs. The detail matters because it foreshadows one of her core insights: education was never separate from power. Who gets to teach, where they get to teach, what they are paid, what they are allowed to say—these are political questions disguised as administrative policy.

For decades, Clark worked as an educator across South Carolina, including long stretches in Columbia and Charleston. She was not merely a classroom instructor; she was a civic actor in a profession that, for Black women, carried both prestige and vulnerability. Teachers were community leaders, but also easy targets for retaliation, because their salaries came from public institutions controlled by white officials.

Clark continued her own education during summers, eventually studying under W. E. B. Du Bois at Atlanta University and earning a bachelor’s degree from Benedict College in 1942 and a master’s degree from Hampton Institute in 1946. Her academic persistence underscored a philosophy she would later systematize for others: learning is not simply self-improvement. It is a tool that widens the range of choices available under constraint.

Her growing political consciousness found an organizational home in the NAACP. Through the NAACP and allied campaigns, she pushed against structural inequities embedded in Southern schooling—pay disparities between Black and white teachers, hiring restrictions, and the broader architecture of segregation that treated Black education as a budgetary afterthought.

This is where Clark’s story begins to resemble many others in the era: activism paired with punishment. South Carolina’s political establishment understood that teachers were dangerous precisely because they were credible. A teacher who taught adults to read was one kind of threat; a teacher who taught adults to demand rights was another. Clark became both.

Paying for membership: Firing, pressure, and the cost of refusing to recant

In the 1950s, as Cold War suspicion fused with Southern segregationist backlash, civil-rights activism was increasingly framed by opponents as subversive. Organizations like the NAACP were targeted through legal harassment, public intimidation, and loyalty-style requirements aimed at public employees. Clark, a public-school teacher, was put in the crosshairs.

Accounts of this period consistently emphasize a defining moment: Clark was fired from her teaching job in the early 1950s after refusing to renounce her NAACP membership. Losing a job was not just an economic blow; it was an attempt to exile her from legitimacy, to separate her from the institutional platform that made her influence scalable. It also carried the threat of long-term insecurity, including the loss of accumulated benefits and professional standing. The message from the state was simple: political participation would be punished through livelihood.

Clark responded in the way she most often did—by moving her work to places the state did not control as easily. If formal classrooms could be taken away, she would build informal ones. If the public system refused to treat Black adults as full citizens, she would teach them how to claim citizenship anyway.

The irony is that what the state tried to suppress became, through Clark’s next chapter, one of the movement’s most effective tools.

Highlander: The training ground, the controversy, and the laboratory for citizenship

By the mid-1950s, Clark’s path led her to the Highlander Folk School in Tennessee, an interracial training center devoted to labor organizing and civil-rights education. She began working there full time in 1956, and the institution became the laboratory where her most enduring innovation took shape.

Highlander was controversial in the way effective institutions often are—especially in a South where interracial organizing was treated as provocation. The school drew surveillance and political attacks; later it was forced to close in 1961 under state pressure. But in the years before that closure, Highlander offered Clark something rare: space to build curriculum with the explicit goal of political empowerment.

One famous photograph captures the convergence of personalities and purpose—Septima Clark and Rosa Parks at Highlander in 1955. The image has become a shorthand for Highlander’s role in the movement: a place where local people and emerging icons shared training, strategy, and the kind of quiet reinforcement that makes courage sustainable. Clark’s role there was not as a celebrity instructor but as a designer of method—how to teach people, quickly and effectively, what they needed to know to confront voter suppression.

Clark understood that literacy tests were not neutral assessments; they were political weapons. The Smithsonian’s National Museum of American History notes that literacy tests were used in the South to prevent African Americans from registering to vote, and that the Voting Rights Act ended their use in the South in 1965 (and later nationally). The tests’ power was not only in the questions, but in the discretion granted to registrars—subjectivity masquerading as standards.

So Clark built a counter-weapon: instruction that treated literacy as civic armor. Not theoretical literacy, but functional literacy tied to forms, to constitutions, to the vocabulary of local governance. In Southern Cultures’ account of her work, the citizenship education program linked self-help to politics: teachers used charts to explain government structure and led discussions about what citizens do; they taught practical skills like budgeting, balancing checkbooks, and applying for Social Security benefits. These details reveal Clark’s sophistication. She was not simply preparing people to pass a test. She was teaching them to navigate—and reshape—the administrative state that governed their lives.

The first Citizenship Schools: Everyday materials, extraordinary consequences

The Citizenship Schools emerged from a core premise that was both radical and pragmatic: if the state designed barriers that relied on illiteracy and intimidation, then literacy and confidence were forms of direct action. Clark’s approach was adaptive. The SNCC Digital Gateway describes how she used “everyday materials” to teach big questions—reading catalogues, writing on dry cleaner bags when chalkboards were unavailable, and insisting that the process of learning could happen anywhere.

That “anywhere” mattered because visibility could be dangerous. In many communities, formal “political meetings” drew scrutiny, threats, and violence. A class, however—especially one hosted in a home or a community space—could appear less provocative, even as it quietly produced political capacity. Over time, Citizenship Schools operated in kitchens, beauty parlors, and under trees, as later recollections underscore.

Clark’s genius was not merely that she taught people to read. It was that she designed a system that could reproduce itself. Train local teachers; those teachers train others; communities become less dependent on outside organizers. This model aligned with Clark’s broader distrust of top-down leadership. Real power, she believed, was durable only when it was locally owned.

It is difficult to overstate how disruptive this was. Voter suppression depended on isolation: make people feel alone in their confusion, alone in their fear, alone in their failure to interpret the state’s requirements. Citizenship Schools created the opposite condition—collective learning that normalized competence, that turned intimidation into a shared problem with shared strategies.

Her work relied on spaces and networks that women often controlled—homes, churches, beauty shops—and it was powered by relational labor, the art of persuading someone who is tired, embarrassed, or afraid to try again. Clark built political infrastructure out of social infrastructure, honoring what already existed in Black communities rather than importing a model that required permission.

From Highlander to SCLC: Institutionalizing the model, and fighting for respect

When Tennessee forced Highlander to close in 1961, the Citizenship Education Program did not disappear. It migrated. The Southern Christian Leadership Conference established its own Citizenship Education Program modeled on Clark’s workshops, and Clark became SCLC’s director of education and teaching.

Here, Clark encountered another set of challenges—less about white hostility and more about movement hierarchy. The SCLC, dominated by male ministers, valued her work but did not always value her authority. Later reflections note bluntly that the organization “didn’t respect women too much,” and Clark herself confronted sexism within activist circles while continuing to nurture women leaders and teachers.

This tension is part of what makes Clark’s story so instructive. Movements are not automatically just because they seek justice. They carry the biases of their time. Clark navigated this by focusing on outcomes and by protecting the work’s integrity: the curriculum, the teacher training, the local leadership pipeline. King’s praise of her “expert direction” was real, and he understood the program’s strategic value. Yet praise did not necessarily translate into power-sharing.

Still, under SCLC’s umbrella, the Citizenship Schools expanded dramatically, reaching across the South and helping generate the skill base that made major registration drives possible. Accounts vary on the exact number, but multiple sources describe the program’s growth into the hundreds of schools, with Clark central to training teachers and shaping curriculum.

The point is not the statistic; it is the scale. Clark took what could have remained a localized experiment and helped turn it into a movement-wide infrastructure.

Citizenship as practiced life: Why Clark taught budgets, forms, and local boards

One of the easiest ways to misunderstand Septima Clark is to reduce her to a voting-rights technician—as if her work began and ended with registration. In fact, she taught citizenship as an everyday practice, an orientation toward public life. The Southern Cultures account emphasizes that students learned not only rights, but responsibilities: establishing local voting leagues, paying taxes, lobbying for municipal services, and understanding citizenship as something exercised on behalf of the broader community.

This is where Clark’s work begins to resemble what modern civic educators call “capacity building.” She wasn’t simply moving people through a pipeline toward a single act—casting a ballot. She was building a public: people who could interpret a problem, identify decision points, and act in coordinated ways.

The curriculum’s emphasis on household budgets and Social Security forms was not a diversion from politics; it was politics. It taught people how the state touched their lives and how to demand fair treatment inside those systems. It also restored dignity. A person who has been told, repeatedly, that they are incapable begins to believe it. A person who successfully fills out a form, reads a document, understands a chart, explains local government to a neighbor—that person begins to see themselves differently. Clark recognized that self-conception is a political resource.

It is also why the Citizenship Schools could outlast specific campaigns. Once you teach someone how to learn—and how to teach—your program becomes less dependent on your presence. Clark was building generational knowledge transfer, a tradition of community education as movement work.

Recognition and erasure: Why “unsung” became a recurring descriptor

Many retrospectives describe Clark as “unsung,” “little-recognized,” or “unknown” outside specialist circles—even while acknowledging her centrality. The pattern is familiar in American history: work coded as educational, domestic, or “supportive” is treated as secondary to the work coded as leadership. In movement storytelling, the microphone often outranks the chalkboard.

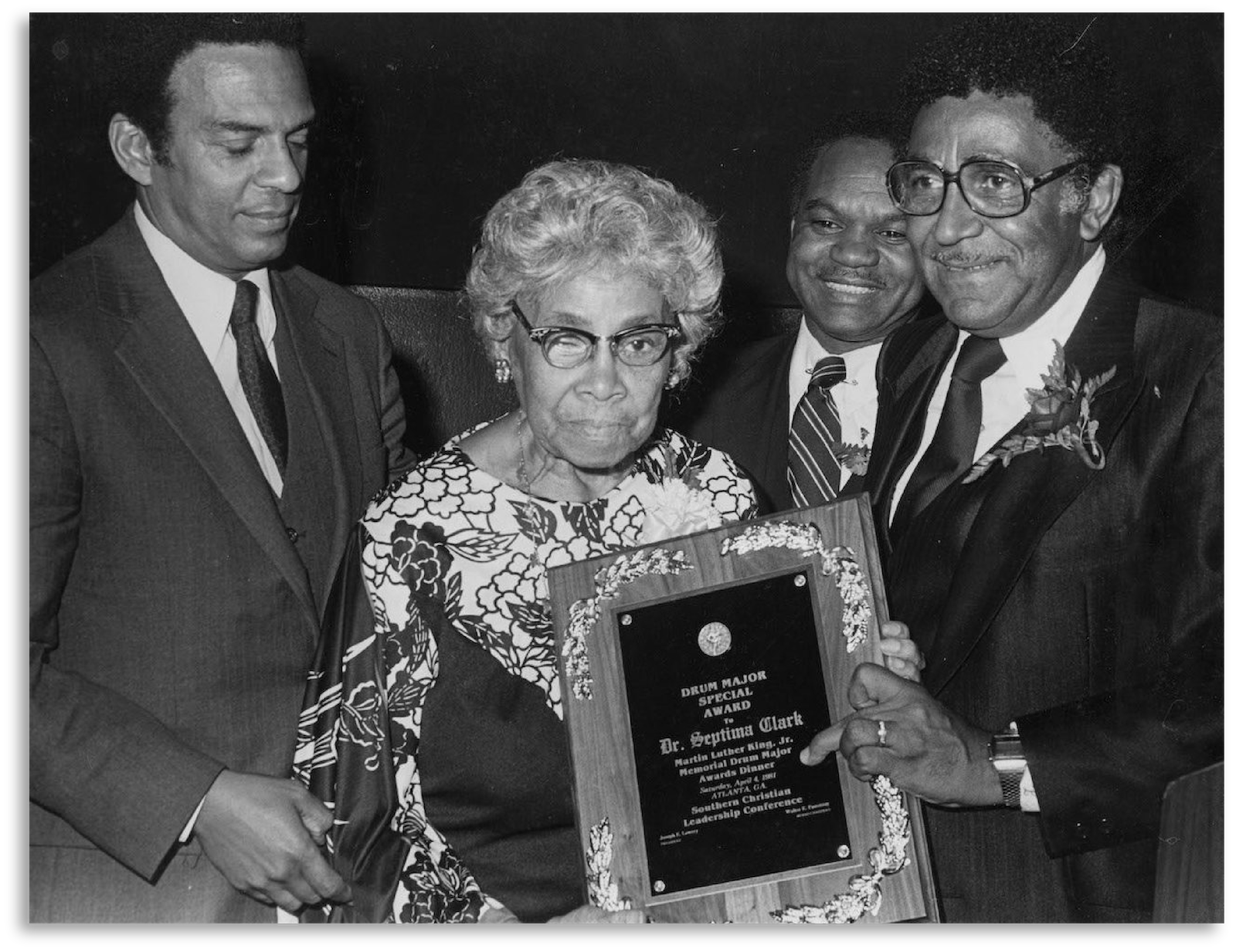

Clark’s marginalization was not total. She received awards later in life, including recognition noted in contemporaneous reporting and institutional histories. She was active enough in public life to be elected to the Charleston school board in the 1970s, according to The Washington Post’s obituary listing. But the arc of recognition lagged behind the arc of impact.

Part of the delay stems from how the country prefers to narrate social change. It likes heroes who look like singular forces of nature. Clark’s heroism was procedural. She built systems. She trained trainers. She made other people powerful.

This is also why she resonates now, in an era once again defined by fights over access to voting, control of curriculum, and the weaponization of administrative rules. Clark’s story suggests that democratic regression is often bureaucratic, and so is democratic resistance. You fight paperwork with knowledge. You fight intimidation with competence. You fight disenfranchisement with organized, local instruction.

A teacher’s realism: Grief, setbacks, and the discipline of continuing

Any serious account of Clark’s life must resist turning her into a plaster saint. She carried personal burdens, faced repeated institutional retaliation, and worked within movements that did not always honor her. Southern Cultures notes “personal tragedies” that followed her earliest political involvement and created setbacks, even as relocation and networks of Black women helped her regain footing. Clark herself acknowledged failure as part of the work, warning against narratives that treat movement-building as a straight ascent.

This realism is essential to her legacy because it is transferable. A movement built on myth requires constant inspiration; a movement built on method can survive disappointment. Clark’s gift was not optimism alone. It was the discipline of continuing, of iterating, of training others to do the same.

The broader landscape: Literacy tests, suppression, and why the Citizenship Schools mattered

Clark’s work emerged in direct response to a voter-suppression regime that used literacy tests and registrar discretion to keep Black citizens from the ballot. The Smithsonian details how such tests functioned as exclusionary tools and how federal law later curtailed them. The Guardian, in a historical look at voter suppression, notes that across the South Black voters prepared for these tests by attending Citizenship Schools—linking Clark’s model to the regional reality it was designed to confront.

The Citizenship Schools mattered not only because they helped individuals pass tests, but because they undermined the psychological architecture of suppression. Literacy tests depended on shame—on convincing adults that it was too late to learn, too risky to try, too humiliating to fail. Clark’s classes turned learning into a collective act that could absorb embarrassment and transform it into progress.

They also mattered because they produced local leadership that could sustain organizing beyond charismatic interventions. The SNCC Digital Gateway highlights Clark’s insistence that education was key to political, economic, and social power, and that her approach preceded and influenced later movement educational efforts, including Freedom Schools.

In other words, Clark helped build the movement’s civic spine.

Later years: Local governance, public honor, and an afterlife in institutions

Clark remained engaged into her later decades. The Washington Post’s 1987 obituary listing describes her long activism, her role at Highlander in developing the citizenship program, her work with SCLC, and her election to the Charleston school board in 1974. That local officeholding is easy to overlook, but it is symbolically consistent: a woman who taught people to understand school boards eventually sat on one, bringing movement experience into governance.

Recognition accumulated as well. Accounts note honors including President Jimmy Carter’s Living Legacy Award and state-level recognition. These awards were meaningful, but they also reveal how often American recognition arrives after the most dangerous years have passed—when it is safer to celebrate a dissenter than to listen to her.

Clark died on December 15, 1987, on Johns Island, South Carolina. By then, the movement she helped build had already been absorbed into national narrative, sometimes in forms that minimized the kind of work she represented. Yet her methods continued to circulate—through training traditions, adult education programs, and the broader idea that political power can be taught.

Septima Clark in the present tense: What her work explains about today

It is tempting to treat Septima Clark as a historical correction—one more name to add to the canon. The more urgent reading is that she offers an analytic framework for the present.

Consider what her career reveals:

She shows how suppression is often enforced not by spectacular violence alone but through administrative friction—forms, tests, discretionary gatekeeping, and the quiet threat that “you don’t belong here.”

She shows how resistance can be built out of ordinary spaces and ordinary relationships—kitchens and beauty parlors, neighbors teaching neighbors—so long as the pedagogy is serious and the strategy is scalable.

She shows that civic education is not neutral. Teaching someone how government works is not simply “information.” In a society structured by exclusion, it is redistribution—of competence, of confidence, of agency.

And she shows, uncomfortably, how even righteous movements can reproduce inequality inside their own ranks, requiring women like Clark to fight two battles at once: against the external system of white supremacy and against internal patterns of sexism that limit who is recognized as a strategist.

In that sense, Clark’s legacy is not a monument. It is a set of tools.

The democracy Septima Clark tried to build

Septima Clark’s genius was that she treated democracy as something you could practice. Not in the abstract, not as a slogan, not as a promised inheritance, but as a learned behavior—like reading, like writing, like teaching. She understood that the vote is not merely a right; it is the visible edge of a deeper capacity: to interpret the world, to navigate institutions, to demand services, to persuade neighbors, to sustain collective action after the cameras leave.

She was called the “Mother of the Movement,” but the better descriptor may be architect. She designed structures that held. She built a model sturdy enough to survive her firing, sturdy enough to migrate from Highlander to SCLC, sturdy enough to scale across communities that were told—by law, by custom, by violence—that they did not have the standing to claim full citizenship.

And she did it in the most radical way imaginable in a country addicted to spectacle: she taught.