Fifty-plus years after its premiere, Sanford & Son continues to matter because it captures a transitional moment in American media: when networks flirted with social realism

Fifty-plus years after its premiere, Sanford & Son continues to matter because it captures a transitional moment in American media: when networks flirted with social realism

By KOLUMN Magazine

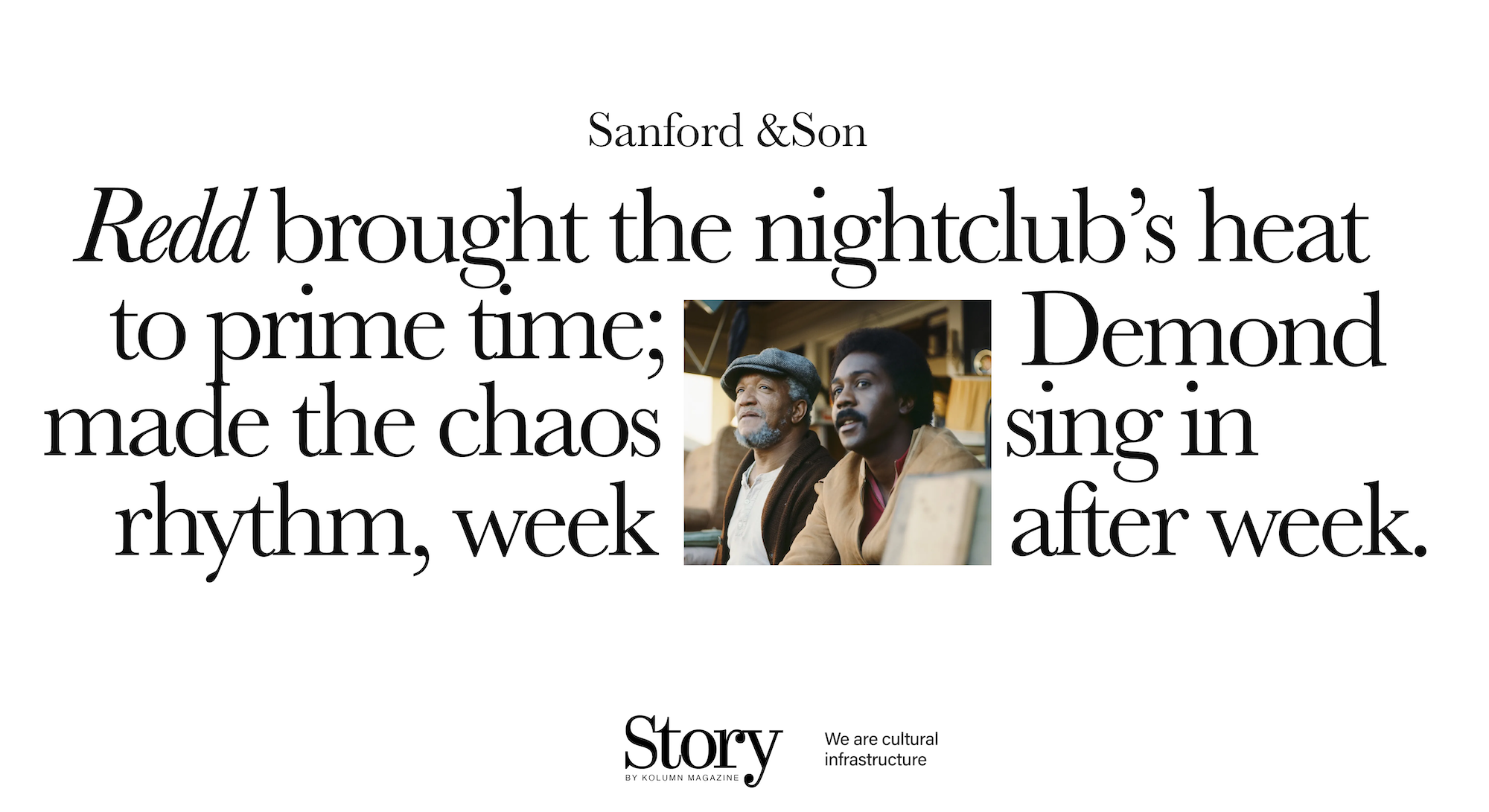

The easiest way to remember Sanford & Son is through its loudest artifacts: a junkyard gate, a cheap living room set, a theme you can hum after two notes, and a constellation of lines—“You big dummy,” “I’m coming to join you,” “This is the big one”—that became shorthand for an entire era of television comedy. But the show’s real story is less tidy than its reruns suggest. It was a production built on adaptation and improvisation, a cultural experiment funded by network anxiety, and a workplace shaped by the combustible chemistry between its two centers: Redd Foxx, the seasoned “chitlin’ circuit” performer whose nightclub act had to be “sweetened” for broadcast America, and Demond Wilson, the Broadway-trained actor who made the chaos work by refusing to match it beat for beat.

To call it groundbreaking is accurate, but incomplete. It was groundbreaking in the way a pickaxe is: it breaks a surface by force, not finesse. The series took a setting that network television had rarely treated as comedic real estate—South Central Los Angeles, in the shadow of the Watts uprising and the continuing political debates about policing, poverty, and Black life—and insisted it could hold jokes that were not polite and characters who were not designed to reassure.

And it did all of that while operating inside the strictest constraints of its time: three networks, a small handful of gatekeepers, and an industry that, even as it began to sell “relevance,” still treated Black-centered stories as conditional—hits when they performed, risks when they demanded anything in return.

This is the long arc of Sanford & Son: development as translation, production as negotiation, and a lifespan that tracks not only ratings but the limits of what prime time could absorb before it snapped back into safer forms.

From “Steptoe” to “Sanford”: The art of importing a premise without importing its meaning

Sanford & Son began as an American answer to a British question. The source material, Steptoe and Son, had already proven that a two-hander about a junk dealer father and his son could carry comedy and pathos in the same breath. The American version kept the skeleton—father, son, salvage business, domestic claustrophobia—but rebuilt the muscles and nerves to fit U.S. race, class, and broadcast standards.

The show was developed under the umbrella of Tandem Productions, with Bud Yorkin in a day-to-day leadership role and Norman Lear associated with the project (often described as an uncredited guiding hand, given his wider production slate). The series aired on NBC beginning January 14, 1972, and ran for six seasons, ending March 25, 1977.

Adaptation wasn’t merely a business move; it was a creative strategy that fit the early-1970s network environment. Lear’s biggest successes of the era were built on taking British formats and reengineering them for American politics and American friction—most famously All in the Family. In that context, Sanford & Son wasn’t an outlier; it was part of a pipeline: import a sturdy premise, then wire it into American anxieties.

But the transformation from “Steptoe” to “Sanford” required a decision with cultural weight: the father at the center would be a Black man in Watts, and the comedy would be allowed—encouraged—to swing at race, prejudice, and intra-community tension without the softening balm of a weekly moral lesson. The Television Academy’s retrospective notes that, unlike many Lear-era comedies, Sanford & Son didn’t consistently lean into drama; it mined conflict for jokes and often left the bruise visible.

This tonal choice is central to the show’s identity. It explains why some early reviewers described the adaptation as “sweetened” for American viewing—network television demanded that Foxx’s raw nightclub persona be reshaped—yet the finished product still felt sharper than most sitcom fare.

Casting the contradiction: Why Foxx was both the point and the problem

From a production standpoint, Redd Foxx was the premise. Foxx had built a career on party records and stand-up that pushed language and sex and insult beyond what television normally allowed. The idea that he could anchor a prime-time sitcom sounded, even to people in the business, like a dare. A 50th-anniversary account drawn from an Associated Press interview captured the skepticism in a line that stuck: inviting Foxx onto network TV, Wilson said, would be “like bringing a dog to a cat party.”

Networks didn’t just buy Foxx’s talent; they bought his danger and then tried to insure against it. In practice, that meant calibrating the edge without dulling the blade. The Television Academy’s production history points to the tension between “reality” and comedy—how the show could begin with an ordinary setup and then launch into outsized situations—because the series was never intended to be documentary-realistic. Its realism was emotional: the desperation behind a hustle, the sting behind a joke, the mourning behind a widower’s theatrics.

Foxx’s performance made that emotional realism possible because he played Fred Sanford as a man who weaponized comedy to avoid vulnerability. The fake heart attacks were funny, but they were also a manipulation tactic, a form of control in a world where Fred had very little. That’s one reason Foxx mattered culturally: he brought a working-class Black patriarch to prime time who wasn’t tidy, aspirational, or sanitized. He was messy, hilarious, selfish, affectionate, and scared.

It’s also why he became a production risk. When you build a series around a star whose public identity was built in spaces television historically treated as too Black, too adult, too unruly, you inherit the volatility of that identity. And eventually, the volatility arrived as labor conflict.

Finding Lamont: Demond Wilson as the show’s discipline and moral tempo

If Foxx was the explosion, Demond Wilson was the architecture that kept the building standing.

The most revealing way to talk about Wilson’s contribution is not to say he “played the straight man,” because that term can sound passive. Wilson played the stabilizer. Lamont Sanford is the character who understands consequences—rent, debt, reputation, police attention, community judgment. He’s the one who hears the lie as it leaves Fred’s mouth and tries to stop it before it becomes a disaster. The show’s comedy depends on that friction: the father’s appetite for chaos against the son’s insistence on order.

The Television Academy’s retrospective emphasizes the series’ “prickly” father-son relationship and the absence of the late wife, Elizabeth, as a persistent emotional presence. That absence matters because it gives Lamont a grief he can’t quite name. He’s not simply managing his father; he’s living with the fact that the one person who might have managed Fred is gone. In that context, Wilson’s restraint becomes not just comedic technique but character truth.

Wilson also carried the show in a literal, industrial sense during moments when Foxx did not show up. In 1974, Foxx walked off the series in a salary dispute, and press coverage of Wilson’s death this week underscores that reality plainly: Wilson kept the show “humming” during Foxx’s absence.

That kind of endurance often goes uncelebrated because television history tends to worship the “star.” But sitcom production is not a solo sport. When the lead is missing, the show either collapses or it reveals what the ensemble can do. In those weeks, Wilson’s value was not theoretical. It was the difference between an airable season and a crisis.

The writers’ room problem: Representation on camera, scarcity behind it

The story of Sanford & Son can’t be told honestly without confronting a structural contradiction noted by the Television Academy: despite the predominantly Black cast and the show’s immersion in Black working-class life, the writing staff in that era was often mostly white, in part because there were so few Black writers established in Hollywood.

The retrospective also notes that major Black comedy figures—including Richard Pryor and Paul Mooney—contributed scripts. That detail is crucial: it suggests the show’s voice was not monolithic. It was a negotiated sound, shaped by a mostly white production apparatus that nonetheless sought Black comedic authenticity, often by borrowing it from Black geniuses who were sometimes treated as contractors rather than power-holders.

This is one reason the show feels double-edged in retrospect. It expanded the visibility of Black characters and Black humor, but it did so within an industry system that still concentrated creative authority elsewhere. In other words: the show pushed boundaries, but the boundaries were still owned by someone.

Borrowed episodes, new rhythms: How the first season was built

One of the least sentimental but most informative aspects of the show’s development is the mechanics of adaptation. A critical analysis from The A.V. Club notes that Sanford & Son reinterpreted an unusually large number of Steptoe and Son episodes early on—so many, the piece argues, that it bordered on a kind of repeated stage translation rather than a loose inspiration.

That practice was not unique in TV history—imports often begin by shadowing source material—but the scale matters because it reveals how networks and producers manage risk. In a new series, especially one with a Black lead in a prime-time environment that still questioned broad audience appetite, the safest creative move is to rely on proven story engines. Early “borrowed” plots are a form of insurance.

But even when the skeletons were imported, the show’s rhythms had to be invented. Foxx’s insult-comedy cadence did not sound like British class satire. Wilson’s exasperated patience did not mirror the same father-son dynamic as in the original. And the American setting—Watts, South Central Avenue—changed the stakes of every hustle and every insult. The show was borrowing structure while forging tone.

The Quincy Jones factor: The theme as a branding weapon

The show’s opening theme, “The Streetbeater,” composed by Quincy Jones, is more than a catchy hook. It’s a sonic branding decision: it signals urban cool, movement, and confidence, telling the audience in seconds that this world is different from the pastel suburban sitcoms that dominated earlier decades.

It’s easy to treat theme music as trivia. But in the broadcast era, a theme was a contract with the viewer. It taught you how to watch. Jones’ theme makes the junkyard feel like a stage, not a sad lot. It frames the characters as kinetic rather than defeated. And it helped embed the show into pop memory, making Sanford & Son instantly recognizable even to people who can’t name an episode.

Making Watts legible to America: Setting, stereotype, and the tightrope of “ghetto-com” television

The Television Academy analysis situates the show in a lineage: it arrived before a wave of network comedies centered on Black families in poor neighborhoods—sometimes dismissed as “ghetto-coms”—and it mined laughs in a setting still politically charged after the Watts uprising.

This is where the show’s reputation becomes complicated. On one hand, it brought working-class Black life to the center of prime time. It gave America a Black father and son whose relationship was the story—not side characters orbiting a white lead. On the other hand, some of its humor leaned into broad caricature, and some of its storylines chased farce at the expense of grounded community detail. Both can be true.

What’s often missed is that the show’s setting functioned as both representation and provocation. The junkyard is not merely a workplace; it’s a metaphor for salvage—what you can rebuild from what the country discards. That metaphor lands differently depending on who is watching. For Black audiences, it can read as recognition, sometimes uncomfortably so. For white audiences, it can read as an exoticized backdrop, a safe way to “visit” poverty via jokes.

The show’s genius—and its ethical challenge—was that it could be enjoyed without being understood. It could be consumed as catchphrases while carrying, underneath, an argument about class pressure and Black survival strategies. That dual readability is part of why it became a hit.

The production as a workplace: Speed, control, and the cost of being “sweetened”

Network sitcom production in the 1970s was an assembly line disguised as artistry. Episodes were written fast, rehearsed hard, taped efficiently, and revised constantly to satisfy sponsors, standards departments, and audience expectations. Foxx’s comedy, by reputation and by design, resisted containment. He came from live performance traditions where a comic could stretch time, ride a crowd, and improvise. Television required marks, timing, and a language that wouldn’t trigger censors.

A 1972 trade review republished by The Hollywood Reporter described the adaptation as “sweetened somewhat for American viewing.” That phrase is polite, but it signals a serious production labor: translating Foxx’s adult persona into a version that could air at 8 p.m. without spooking advertisers. The “sweetening” wasn’t only about profanity; it was about intent. Nightclub Foxx could be meaner, darker, more sexual, more direct about white hypocrisy and Black pain. Network Foxx had to be sharp without being radioactive.

Wilson’s performance helped manage that transformation because Lamont could receive insults and redirect them into a family dynamic rather than a broader social confrontation. In effect, Wilson helped domesticate Foxx’s danger—without removing it entirely.

Ratings as power: Why the show’s success mattered inside the network

Sanford & Son wasn’t merely popular; it was strategically important. It ran in what’s often called a tough timeslot and still landed in the Nielsen top ten for multiple seasons, peaking at number two in the ratings in the early- to mid-1970s, according to compiled ratings histories.

From a network perspective, that kind of hit does two things at once. It gives you confidence and it creates dependency. Confidence because the show proves an audience exists for something executives feared might be “too niche.” Dependency because the show becomes an anchor: the programming around it, the ad sales tied to it, the brand identity a network builds around “Friday night” or “must-see” lineups.

The wiki-sourced production history (which aggregates multiple reference works) notes how the show helped lift NBC’s Friday night lineup and how its ratings strength made it a pillar for the network. Even if you treat those aggregated accounts cautiously, the broader fact is well supported by multiple retrospective sources: the series was one of NBC’s defining hits during its run.

That success also changes negotiations. A hit show gives actors leverage—until the network decides it doesn’t.

The walkout: Redd Foxx, contracts, and a show forced to improvise

In the midst of taping for the 1973–74 season, Foxx walked off the show during a salary dispute. Production histories describe a high-stakes conflict: Foxx sought more money and, by some accounts, an ownership stake; the producers responded aggressively, including litigation; and the show wrote Fred Sanford out temporarily by sending him to St. Louis for a funeral, letting supporting character Grady fill the space.

This is a crucial chapter because it exposes the difference between public mythology and industrial reality. The public sees a “family” sitcom. The industry sees a product with human labor attached. When a lead actor leaves midstream, the product is threatened, and the response is not sentimental. It is legal, financial, and logistical.

It’s also the period that clarifies Wilson’s contribution as more than acting. When Foxx was gone, Wilson wasn’t simply “still there.” He was the continuity mechanism. He had to keep the show’s emotional stakes coherent while the writing staff re-engineered storylines around an absence. That’s not glamorous work, but it is the kind of work that keeps a hit from collapsing into chaos.

Later reporting and obituaries continue to cite this moment as evidence of Wilson’s steadiness, and of how much the show relied on the Fred–Lamont axis even when only one half was available.

What the audience didn’t see: Labor politics inside a “groundbreaking” sitcom

The show’s behind-the-scenes tensions were not unique. What makes them significant is their relationship to race and value.

In the 1970s, Black performers were winning visibility on network television, but visibility did not automatically translate into equitable power. When a Black-led show became a major hit, it created a new question: who gets to profit from proving the network wrong? Often, the answer was still shaped by old hierarchies—producers, studios, and networks, with performers fighting for a larger share.

Foxx’s dispute fits that pattern. So does the broader imbalance the Television Academy points to: a mostly white writing infrastructure generating Black dialogue, with a few Black writers brought in but not necessarily positioned as decision-makers.

This is not an argument that the show shouldn’t be celebrated. It’s an argument that celebration should include an accounting.

The ensemble as a second engine: Aunt Esther, Grady, Bubba, and the world beyond the gate

A common mistake in retelling Sanford & Son is to treat it as a two-man show with occasional visitors. In reality, the series built a durable ecosystem of supporting characters that functioned as pressure valves—bringing in new kinds of conflict so the father-son dynamic didn’t exhaust itself.

The Television Academy’s history notes how the show introduced audiences to comics and actors who had often been sidelined by Hollywood, and it names key presences, including Aunt Esther and Grady. The significance is twofold. First, it widened the range of Black comedic archetypes on prime time: not one “respectable” Black character to reassure, but a messy, quarrelsome community. Second, it built narrative resilience. When Foxx walked, the show could lean on the ensemble. When storylines needed variety, these characters expanded the world.

Wilson, again, served as the bridge. Lamont was the character who connected Fred’s chaos to the wider community, and who could plausibly interact with everyone—from the churchgoing moralists to the hustlers and opportunists. Without Lamont, the ensemble could have turned into pure sketch. With him, the world felt like a neighborhood.

The lifespan question: Why it ended when it did

The series ended in 1977. Production histories commonly attribute the ending to a mix of factors: ratings softening late in the run and Foxx leaving for another opportunity—often cited as a move toward a new project with a rival network—creating the conditions for NBC to conclude the show rather than rebuild it indefinitely.

Here, it’s important to avoid oversimplification. Shows rarely die for one reason. They die because the economics and the personalities and the schedule calculus converge. A star’s willingness to stay matters. A network’s willingness to pay matters. The audience’s size matters. And the industry’s appetite for risk matters.

What we can say with confidence, based on mainstream reference histories, is that Sanford & Son ran six seasons, ended in 1977, and that Foxx’s career decisions and contractual conflicts were central to the show’s instability and ultimate closure.

What we can also say—based on Wilson’s career arc and public accounts—is that the end of the show did not end its cultural life. The series continued in reruns, influenced the business logic of Black sitcom greenlights, and became a permanent reference point in American comedy.

Afterlife: Spin-offs, revivals, and the long shadow of a hit

The show’s official run ended, but the brand did not. Reference histories point to attempts to extend or revive the universe: spin-offs, continuations focused on supporting characters, and later efforts to relaunch the concept under related titles.

These afterlives reveal how networks and studios think about “legacy” television: as intellectual property that can be repackaged when nostalgia becomes bankable. But they also reveal an emotional truth about the original: the chemistry between Foxx and Wilson was not easily replicable. The show’s engine wasn’t merely the premise. It was the relationship—Foxx’s storm and Wilson’s levee.

What Foxx and Wilson built together: A performance system, not just a show

When people talk about the show’s “chemistry,” they often mean something vague: that the leads “worked well together.” The more precise claim is that Foxx and Wilson built a performance system.

Foxx’s Fred Sanford is a master of escalation. He begins at complaint and climbs to insult, feigned illness, spiritual melodrama, and self-pity, often within one scene. That kind of performance can easily become exhausting, even alienating. Wilson’s Lamont functions as a regulator. He absorbs the attack, responds with a look or a line that resets the rhythm, then pushes the scene forward. Without that regulation, Foxx’s style might have overwhelmed the form; without Foxx’s aggression, Wilson’s restraint might have lacked tension. Together, they created a rhythm that could carry 22 minutes a week for years.

The Television Academy’s retrospective frames the show as a bridge: it helped make space for later Black-centered sitcoms and helped establish the template of the stand-up comic turned sitcom star. Foxx fits the second claim; Wilson fits the first in a quieter way. Wilson helped prove that a Black co-lead could be more than a sidekick—could be the moral center, the competent adult, the character an audience trusts to tell them what is real.

That’s a contribution that doesn’t always win awards, but it wins longevity.

The show’s ethical legacy: Boundary-pushing, and what it pushed aside

If you’re writing a rigorous history of Sanford & Son, you can’t treat it as either pure progress or pure stereotype. It is both a breakthrough and a compromise.

It was progress because it put Black working-class life at the center of prime time and proved a Black-led comedy could draw mass audiences. It was compromise because it operated within a production ecosystem that often lacked Black creative control at the highest levels, and because network standards required a translation of Foxx’s authentic persona into a less threatening version.

Those contradictions are not incidental. They are the story. The show’s development and production reveal how television “advances”: not by suddenly becoming enlightened, but by discovering profit in what it once avoided, then negotiating the terms of that profit.

Why it still matters now

Fifty-plus years after its premiere, Sanford & Son continues to matter because it captures a transitional moment in American media: when networks flirted with social realism, when Black performers gained unprecedented visibility, and when comedy became a vehicle for arguments that couldn’t yet be spoken plainly elsewhere.

It also matters because of the partnership at its center. Foxx, the veteran of a pre-television Black entertainment economy, brought the unruly power of the club to the living room. Wilson, trained for precision, brought craft, patience, and an emotional intelligence that turned insult comedy into family narrative. The show needed both. American television history needed both.

And if you want a clean moral, it refuses to provide one. Instead it offers something more useful: a case study in how culture gets made—by artists, yes, but also by contracts, schedules, standards departments, and the quiet labor of the person whose name is second on the call sheet and first in the work of holding the scene together.