Hayes keeps making the same argument, in different forms, across different arenas: public education is how a democracy tells the truth about itself.

Hayes keeps making the same argument, in different forms, across different arenas: public education is how a democracy tells the truth about itself.

By KOLUMN Magazine

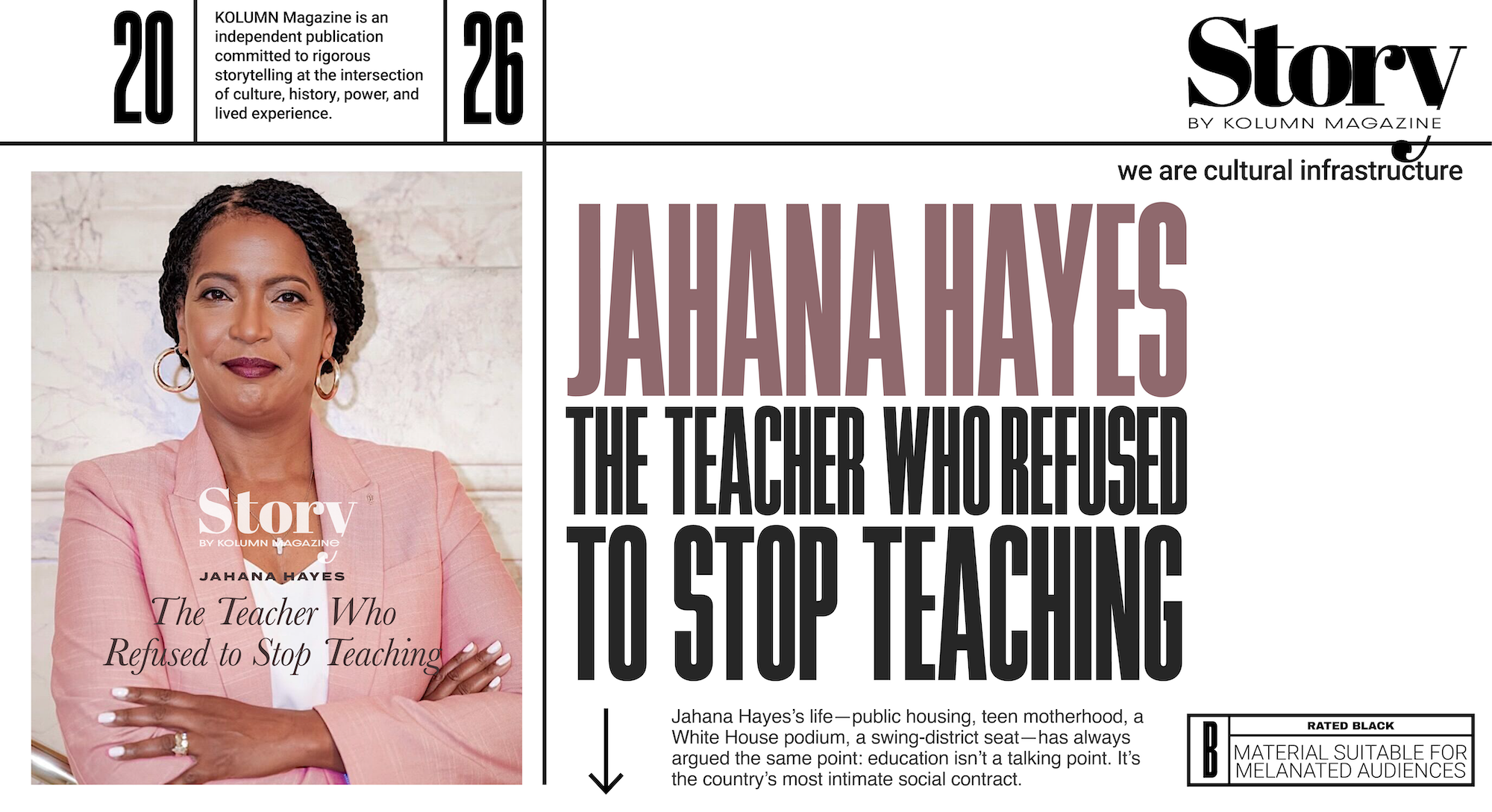

The photograph from May 2016 is the kind of image a country keeps on file for itself: the teacher in the White House, smiling in the Blue Room, as if American democracy is—at least for a moment—still capable of honoring the people who hold it together. President Barack Obama is there, and beside Jahana Hayes stands one of her students, a quiet reminder that the national story is always being drafted in local rooms by people whose names will never trend.

Hayes had been named National Teacher of the Year, a title that can read like a coronation if you want it to, but is better understood as an assignment: carry the profession into public view without letting it be reduced to sentiment. In the years that followed, she would accept another assignment that was less ceremonial and more punishing: carry the logic of public education into Congress, and insist—again and again, through legislation, committee work, campaign cycles, and racialized harassment—that school is not a side issue. It is the issue that tells you what kind of country you are living in, and what kind of country you are willing to build.

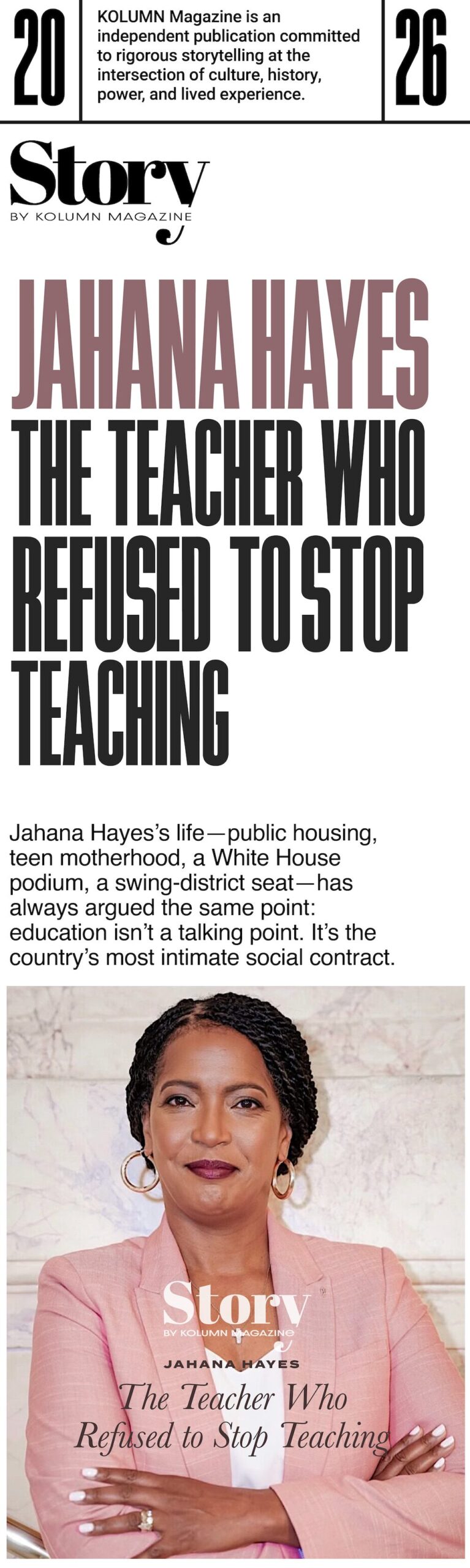

To tell Jahana Hayes’s story with accuracy is to resist the temptation to make it too clean. Her biography is frequently packaged as uplift: a girl raised in public housing in Waterbury, Connecticut, becomes a teen mother, finds her way through college, returns to the classroom, and rises to national recognition before winning a seat in the U.S. House—becoming the first Black woman elected to Congress from Connecticut.

But the neat version, the one built for speeches and campaign mailers, blurs the more durable truth: Hayes’s life is an extended argument for what public education can do when it is resourced and respected—and what it cannot do when it is treated as disposable. That argument began long before Washington, in the specific pressures of Waterbury and in the more universal experience of being a teenager who needed adults to see her as more than the worst thing that had happened to her.

Waterbury’s lesson: Schools as the last stable institution

Waterbury is the kind of American city that politicians invoke when they want to gesture at “forgotten places”—a former industrial hub that has carried economic decline in its body for decades. Hayes grew up in public housing there, in a childhood shaped by poverty and the instability that often shadows it.

When Hayes talks about her early life, she often returns to the adults who intervened without fanfare: teachers who understood that school is not only where children learn content, but where they learn whether they are worth the effort. In a 2016 Washington Post profile published when she was named Teacher of the Year, Hayes described becoming a teen mom and the way educators helped her keep moving forward rather than treating pregnancy as an ending.

This is the first place the throughline becomes visible. Hayes did not emerge from hardship with an abstract belief in “education.” She emerged with a practical belief in public institutions—because, for her, public school was one of the few institutions that could plausibly stabilize a life. In her own White House blog post that week, she framed the “promise of public education” as something real enough to change the course of a student who had every statistical reason to fall through the cracks.

Her path through higher education—via Naugatuck Valley Community College and later four-year and graduate programs—also matters because it reflects the route most Americans actually take, not the elite pipelines that dominate political mythology. It is difficult to build a political identity around that reality; it does not flatter donors or prestige. But it explains why, even as a federal lawmaker, Hayes tends to talk about education as infrastructure rather than aspiration: community colleges, credentialing programs, special education supports, Title I funding—things that determine outcomes more reliably than motivational slogans.

Before she became a national symbol, she became a local teacher. At John F. Kennedy High School in Waterbury, she taught government and history—subjects that, in her hands, were less about dates than about agency: who gets power, how citizens participate, and what it means to be counted. Her classroom was the sort of place where “civics” couldn’t stay theoretical. Students arrived carrying the country’s unanswered questions—poverty, policing, immigration, addiction, racism—and the teacher’s job was to help them translate those conditions into language, analysis, and possibility.

That work shaped Hayes’s politics before she ever ran for office. Teachers learn quickly that policy is not distant. It is the difference between a counselor who has time to call a parent back and a counselor who is responsible for hundreds of students. It is the difference between a classroom with up-to-date materials and a classroom that functions like a salvage operation. It is the difference between a child who has reliable internet access and a child who is asked to “log on” to a future that does not reach their address.

Becoming the nation’s teacher—and refusing the easy story

When Hayes became National Teacher of the Year in 2016, the honor arrived at a volatile moment for education politics. “Reform” had become a blunt instrument. Teachers were publicly celebrated and privately blamed. Debates about evaluations, charters, testing, and union power had turned the profession into a proxy battlefield.

Hayes used the moment to insist on a more honest narrative. In that same Washington Post coverage, she argued for shifting public attention away from a constant focus on “what’s not working” and toward what is working—and what it would take to scale it. It was an educator’s move: diagnose without demeaning, critique without surrender.

She also spoke plainly about technology and resources, refusing to treat inequity as a moral failure of students rather than a material failure of systems. In an EdSurge interview that summer, she described schools’ struggle to keep up with technology—an issue that would later explode into national crisis during the pandemic.

At the National Education Association’s annual meeting, Hayes framed teachers as the adults students look to when deciding what the world will allow them to become. The language was inspiring, but the implication was harder: if the country keeps disinvesting in public education, it is not only underfunding schools—it is undercutting a civic promise.

In Washington, the White House ceremony formalized her as a national representative of the profession. Obama’s remarks that day emphasized the moral seriousness of teaching and the way schools can serve as refuge, particularly for children who need stability most. Hayes herself, in her White House blog post, put the emphasis where it belonged: on the promise of public education, and on the idea that teachers, when supported, can help students translate hardship into trajectory.

Still, being celebrated is not the same as being empowered. The Teacher of the Year platform gives you a microphone, not authority. Hayes could travel and speak, but she could not write budgets or pass laws. And as 2016 gave way to 2017 and 2018—years defined by political acceleration, rising teacher activism, and sharper cultural conflict—the limits of symbolic honor became harder to ignore.

“Can Ms. Hayes go to Washington?” The teacher as candidate

By 2018, teachers across the country were entering politics in visible numbers, fueled by walkouts, funding fights, and the sense that public officials treated schools like an afterthought. The Atlantic’s reporting on the “teacher politician” phenomenon noted both the momentum and the risk of romanticizing it; educators were being turned into symbols in a political culture that consumes symbols quickly.

Hayes became one of the movement’s most high-profile faces—not because she had been looking for a political career, but because her public profile made her candidacy legible. Chalkbeat followed her run closely, framing it as a test case: could a National Teacher of the Year translate classroom credibility into electoral power?

The question was never only about Hayes. It was about whether voters would accept an educator as a lawmaker in a country that often treats education as women’s work—essential, underpaid, and easily dismissed. It was also about whether Hayes could survive the machinery of modern campaigns, which rewards simplification and punishes nuance. Teachers are trained to keep students in the room; campaigns are trained to win the room by any means.

Local reporting in Connecticut captured the moment she decided to run as a kind of epiphany rooted in responsibility: she wanted her students to see that citizenship is participatory, not performative. That impulse—teach by doing—was consistent with her classroom ethos. It also made her candidacy unusually values-forward. She wasn’t running as a technocrat; she was running as a person whose life had been shaped by public systems and who felt obligated to defend them.

Ebony, covering her candidacy that year, presented Hayes as a history teacher on the brink of making history: potentially the first African-American woman to represent Connecticut in Congress. The framing mattered. It placed her campaign within a tradition of Black political firsts, where the candidate is asked to carry both individual ambition and communal symbolism. That burden can mobilize support—and invite backlash.

Hayes won. Education Week called it a historic victory for the nationally recognized teacher, emphasizing both her biography and the symbolic significance of her becoming the first Black woman from Connecticut in Congress.

What came next was the real test: could she legislate education not just as a former teacher, but as a member of Congress operating in a polarized institution?

In Congress, education stops being metaphor and becomes jurisdiction

Hayes entered the House in January 2019, representing Connecticut’s 5th District, a politically competitive seat spanning cities like Waterbury and Danbury and more rural stretches of the state. She joined the committees that made sense for her life and priorities: Education and the Workforce, and Agriculture.

To an outsider, Agriculture can look like a detour. To a teacher, it is part of the same map. Hunger is an education issue. Food systems shape attendance, concentration, and behavior. Hayes’s later leadership role as ranking member on the Agriculture Subcommittee on Nutrition and Foreign Agriculture underscored that she understood the classroom’s dependencies: children learn best when their basic needs are met.

But her defining work has consistently circled back to education—specifically, to the question of whether the federal government will behave like it believes public schooling is a public good.

During the COVID-19 crisis, that question became unavoidable. Schools closed buildings and attempted to open remote classrooms. The country watched, in real time, as inequality became a technical problem: who had internet, who had devices, who had adult supervision, who had quiet space, who had stable housing. Hayes, speaking at an Axios event in 2020, described a brutal data point from her district: after virtual learning began, a school system with roughly 19,000 students had been unable to reach about 30% of them because they lacked the necessary technology or connectivity.

That statistic is not only about broadband. It is about what the country had been willing to tolerate for years: uneven investment that left some districts ready to adapt and others stranded. Hayes framed it as the consequence of long-term disinvestment finally “catching up.”

In January 2021, she introduced the Save Education Jobs Act, legislation designed to stabilize the education workforce by creating an Education Jobs Fund to help retain and create education jobs through fiscal year 2030. In a press release, her office framed the bill as a response to potential layoffs, economic instability, and learning loss.

The bill’s architecture—federal grants flowing to states and then to local educational agencies—was an acknowledgement of what educators know: school staffing is not an abstract line item. It is whether a student has a reading specialist, a counselor, a paraprofessional, a nurse. In a crisis, those positions are often the first to go, precisely because they are not always protected by the same political attention as more visible roles. Hayes’s bill treated those jobs as essential to recovery.

This is where her advocacy for education looks less like rhetoric and more like a theory of governance: protect the workforce that makes schooling possible, because schools are not only places of instruction but places of care.

Clean buses, dirty air, and the politics of the school commute

Hayes’s education advocacy has also been unusually attentive to the physical environment of learning. In 2021, she helped introduce the Clean Commute for Kids Act, proposing major federal investment to transition school buses from diesel to zero-emission vehicles. The bill, as described by her office, emphasized children’s health and the scale of investment required to replace aging fleets.

This is education policy the way teachers often understand it: children arrive at school carrying what the environment has already done to them. Diesel exhaust, asthma rates, missed days—these are not separate from educational outcomes. They are upstream causes.

In 2024, her office highlighted the Biden administration’s nearly $1 billion clean school bus funding announcement and framed it as the payoff of advocacy she had pursued since arriving in Congress, including pushing for inclusion of clean bus funding in the Infrastructure Investment and Jobs Act. She linked the policy to practical outcomes: saving school districts money, creating jobs, reducing emissions, and affecting millions of students.

In a political culture that often treats “education” as curriculum fights and culture wars, Hayes’s approach has been insistently operational. She legislates education through labor, infrastructure, health, and civil rights—the parts of schooling that shape whether any classroom idealism can survive contact with reality.

The Department of Education as a battleground

By 2025, the battle over public education had sharpened into an institutional fight: whether the federal Department of Education should be weakened, decentralized, or dismantled. Hayes introduced the Department of Education Protection Act early in the 119th Congress, pitching it as a shield against efforts to reduce or restructure the department.

Congress.gov’s summary of the bill describes its core mechanism: prohibiting the use of appropriated funds to decentralize, reduce staffing, or alter the department’s responsibilities or functionality compared to its organization on January 1, 2025.

A one-page explainer from Hayes’s office makes the underlying argument explicit: the department is “vital” for ensuring access to quality education, protecting student rights, and supporting programs including Title I and supports for students with disabilities; it frames the act as necessary amid renewed efforts to abolish or weaken the agency.

The policy dispute here is not technical—it’s philosophical. The federal role in education is often misunderstood as a desire to control curriculum, when much of it is about enforcing civil rights and distributing funds designed to reduce inequity. Hayes’s bill treats the department as a civil-rights instrument and a stabilizing force. Her critics, by contrast, often treat federal involvement as an intrusion.

In that sense, Hayes’s legislative posture is consistent with her biography. She knows what it means for a student to need systems to work: special education enforcement, Title I funding, support for English learners, teacher training pipelines. Those are not abstractions to her; they are the difference between “equal opportunity” as language and equal opportunity as lived experience.

The politics of this fight have also been immediate. Coverage in early 2025 captured House Democrats attempting to confront Education Department leadership amid concerns about executive actions aimed at dismantling the agency; Hayes was among the lawmakers present, according to Politico. Connecticut reporting described Hayes condemning plans to hollow out the department and emphasizing the stakes for special education and other programs.

In a different kind of politician, this might read as party-line defense of bureaucracy. In Hayes, it reads like a teacher’s instinct: protect the institution that protects students, because the students do not get a second childhood if adults choose ideology over services.

The backlash curriculum: Racism, visibility, and “Zoom-bombing”

Hayes’s education advocacy has unfolded alongside another reality: she has been forced to navigate the costs of being a Black woman in public office, particularly in an era when political violence and harassment increasingly take digital form.

In October 2020, a virtual town hall hosted by Hayes was hijacked by racist trolls who shouted slurs and flooded the chat with abuse. The Washington Post reported the incident in detail, capturing both the ugliness of the disruption and Hayes’s effort to continue discussing her work in the face of it.

The Root covered her response under a blunt headline, emphasizing that Hayes did not treat the attack as normal or acceptable—and that she spoke about its emotional impact. CT Mirror’s local reporting framed the incident as part of a broader reality for Black officials: the racism was shocking but not surprising.

This matters to the education throughline because Hayes’s public identity is inseparable from her former profession. Teachers are culturally coded as caretakers, expected to absorb harm and keep going. Hayes, the politician, has often been confronted with that same expectation: to be attacked and then to remain composed, grateful, and productive.

In education policy debates, especially those shaped by culture-war rhetoric, that expectation can turn into a trap. If she is angry, she is framed as divisive. If she is calm, the harm is minimized. Hayes has had to learn, in public, what many Black educators already know privately: the work often includes managing other people’s discomfort while advocating for children who do not have political power.

A swing district and the constant test of legitimacy

Hayes represents Connecticut’s most competitive congressional district, and her elections have forced her to make the education case not only to supporters, but to persuadable voters who may not share her party identity. In 2024, she defeated Republican George Logan in a rematch, winning a fourth term. The Associated Press framed the race as closely watched, and as evidence of how difficult it has been for Republicans to win federal races in Connecticut—even while targeting her seat.

The larger context is that Hayes’s district forces her to practice a kind of politics that resembles teaching more than national punditry. In a classroom, you do not win by preaching to the students who already agree with you. You win by keeping the room together long enough for learning to happen. In a swing district, you do something similar: you talk about jobs, health care, schools, and daily life—issues that can still cross partisan identity when presented in human terms.

That’s also why education remains her most credible lane. She can argue about policy with authority that is not easily dismissed as partisan performance. She can talk about technology gaps, staffing shortages, special education compliance, and the relationship between hunger and learning with the authority of someone who has sat in the rooms where those problems show up as faces, not data.

At the same time, close races increase vulnerability. Competitive districts invite heavy outside spending and heightened scrutiny. For a politician like Hayes—whose public story includes poverty and teen motherhood—scrutiny can slide quickly into moral judgment and coded attacks about deservingness. In modern politics, biography is both asset and target.

The educator’s governing style: practical, relational, systems-minded

One way to understand Hayes’s approach is to view her as an education advocate who happens to work in Congress, rather than a politician who occasionally speaks about schools. Her legislative agenda has repeatedly treated education as a system with dependencies.

If schools cannot retain staff, students lose continuity. That’s the logic behind the Save Education Jobs Act.

If students are breathing diesel exhaust twice a day, they lose health—and attendance—and then lose instruction. That’s the logic behind clean bus legislation and her sustained advocacy for clean school bus funding.

If the federal department tasked with enforcing civil rights and distributing key funds is hollowed out, the most vulnerable students lose protection first. That’s the logic behind the Department of Education Protection Act and its emphasis on maintaining the agency’s structure and functionality.

Even her early public messaging as Teacher of the Year foreshadowed this systems view. She spoke about narratives, yes, but she also spoke about resources and technology and the gap between what schools are asked to do and what they are given to do it.

This is a less glamorous kind of education advocacy. It does not generate viral soundbites as easily as culture-war fights. But it aligns with what educators recognize as reality: the success of a classroom often depends on logistics no one wants to fund.

The national frame: Teachers as symbols, education as battleground

Hayes’s rise coincided with a national moment when teachers were pulled into political symbolism. The Atlantic’s skepticism about the “teacher politician” narrative was partly a warning: the public tends to romanticize educators when they serve a story, and to discard them when they complicate it.

Hayes has lived that dynamic. She has been praised as a role model and attacked as a partisan operative. She has been lifted up as proof the system can work and confronted as evidence that the system is under threat. That contradiction is not personal—it is structural. Public education itself is treated that way in American politics: celebrated as an ideal, contested as a budget line, weaponized as a cultural stage.

Word In Black’s coverage of Congressional Black Caucus strategy in the face of “Project 2025” politics and far-right plans placed Democratic lawmakers—including CBC members—in an explicitly defensive posture, fighting to protect institutions and rights that are framed as targets. Hayes’s DOE legislation sits comfortably in that landscape: it assumes, plainly, that public education institutions can be politically dismantled if defenders treat the threat as rhetorical instead of operational.

That’s the deeper throughline: Hayes advocates for education the way someone advocates for something fragile and essential—because she has seen how quickly the promise can be withdrawn.

The unfinished work: What she can and cannot change

A realistic portrait of Hayes also requires acknowledging limits. In Congress, even well-designed bills can stall. Committee power is shaped by party control. Education policy is fragmented across federal, state, and local levels. Teachers can identify problems in minutes that legislatures take years to address.

And then there is the cultural headwind. In the years since Hayes entered Congress, education has become an increasingly intense site of national conflict—over race, gender, curriculum, book bans, and the role of teachers themselves. Those fights can swallow oxygen that could otherwise be used to address staffing shortages, infrastructure, and student supports.

Hayes has not always been at the center of those national headline clashes, and that may be strategic. Her education advocacy tends to live where teachers live: in the practical conditions that make learning possible. That choice is both principled and politically risky. In an attention economy, the work that matters most often gets the least airtime.

Still, Hayes’s persistence suggests she believes education advocacy is a long game—a multi-term project built on repetition, coalition, and incremental wins. That belief is, at heart, pedagogical. Teachers do not teach assuming mastery will arrive tomorrow. They teach assuming growth is possible, and they return the next day prepared to try again.

What her story ultimately insists on

Jahana Hayes is often introduced as a former Teacher of the Year who went to Congress. The more accurate framing reverses the emphasis: she is a public education advocate whose life has forced her to keep proving that schools are worth defending.

She grew up close enough to systemic failure to understand that slogans do not feed children or staff classrooms. She became a teacher close enough to student lives to understand that “achievement” is frequently a proxy for stability. She became a national education figure close enough to power to understand that recognition without investment is performance. And she became a lawmaker close enough to the machinery of government to understand that public education is not self-sustaining—it is sustained by political decisions, year after year.

When she defended remote-learning connectivity as a civil necessity during COVID, she was defending the idea that students without devices still count.

When she introduced a bill to protect education jobs, she was defending the idea that adults in schools are not expendable.

When she pushed for clean buses, she was defending the idea that student health is part of student success.

When she moved to protect the Department of Education, she was defending the idea that civil rights and federal support are not optional features of schooling.

There is a final irony in Hayes’s career: as a teacher, she once had the luxury of believing that if she could reach the student in front of her, she could change an outcome. As a member of Congress, she is forced to operate in a system where outcomes are shaped by forces no single person can control—partisanship, money, media, resentment, and the country’s deep ambivalence about public goods.

And yet she keeps making the same argument, in different forms, across different arenas: public education is how a democracy tells the truth about itself. Not in speeches, but in budgets. Not in rhetoric, but in staffing. Not in slogans, but in whether a child in Waterbury has the same chance to be reached—actually reached—as a child in a wealthier zip code.

That argument is not flashy. It is stubborn. It is, in the most literal sense, educational.