KOLUMN Magazine

This is the story of ten men who, in different ways, carried a sport—and carried the weight of being asked to prove, over and over, what they had already proven.

This is the story of ten men who, in different ways, carried a sport—and carried the weight of being asked to prove, over and over, what they had already proven.

By KOLUMN Magazine

There is a temptation—especially now, in the glow of overdue institutional recognition—to treat the Negro Leagues as a sepia-toned prologue to “real” baseball. The temptation is tidy: it keeps the National and American Leagues at the center, and it turns Black baseball into a holding pattern, a waiting room where greatness killed time until the door finally opened.

But the Negro Leagues were not a waiting room. They were an industry, an improvisational economy, and—at their best—a highly sophisticated baseball culture built under the daily pressures of Jim Crow. They were also a nation-sized argument, conducted in spikes and wool uniforms, against the premise that the color line had anything to do with merit. What white baseball called a “gentleman’s agreement,” Black baseball experienced as theft: of wages, of championships, of security, of the ordinary dignity of being evaluated in the same marketplace as your peers.

When Major League Baseball announced that Negro Leagues statistics from the core “major” Negro Leagues era would be incorporated into the official record, the news traveled like a correction and a confession at once. Suddenly, the leaderboards looked different: Josh Gibson rose to the top of the career batting average list, passing Ty Cobb; the new framing also elevated other Negro Leagues stars whose accomplishments had been treated as adjacent to the sport rather than central to it. The numbers matter—particularly because baseball has always insisted that numbers are its truest language—but the larger truth is that these men were never “almost” major leaguers. They were major leaguers in a major league ecosystem that the country forced to operate beside, rather than inside, the white major leagues.

To write about the leading players of Negro Leagues baseball is to confront two realities at once. The first is the intoxicating artistry: the violence of a Gibson swing, the controlled mischief of a Paige windup, the complete-player authority of an Oscar Charleston, the aerodynamic speed mythology attached to Cool Papa Bell, the left-handed elegance of Buck Leonard, the five-tool quiet of Turkey Stearnes, the almost absurd versatility of Martín Dihigo, the menace and longevity of Smokey Joe Williams, the brainy precision of Pop Lloyd, and the bridging brilliance of Monte Irvin, who lived with one foot in the Negro Leagues and the other in an integrating Major League Baseball.

The second reality is the cost. For every story of a packed ballpark and a payday won, there is a story of travel that treated Black bodies as problems to be managed; of contracts that were informal enough to be broken at whim; of owners and promoters who sometimes protected their players and sometimes exploited them; of medical care that came late or not at all; of primes interrupted by wars, economics, and the exhausting necessity of playing everywhere because the league schedule alone could not reliably pay the bills.

This is the story of ten men who, in different ways, carried a sport—and carried the weight of being asked to prove, over and over, what they had already proven.

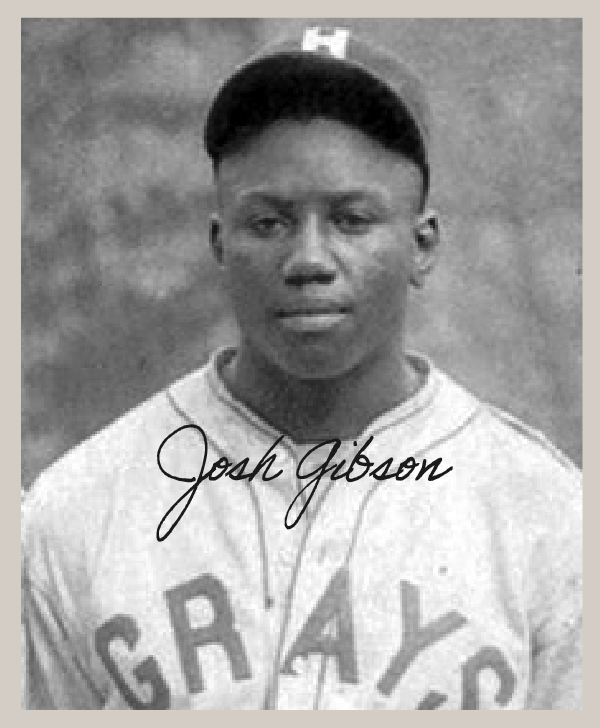

Josh Gibson, the catcher who bent physics and broke time

Josh Gibson is often introduced as myth: the “Black Babe Ruth,” the man said to have hit nearly 800 home runs, the slugger whose longest blasts feel like folklore because they were launched in a world that did not preserve its evidence with the same care it gave white stars. The framing can be flattering and reductive at once. Comparing Gibson to Ruth offers mainstream readers a measuring stick, but it also implies that Black greatness needs a white reference point to be legible.

The more accurate way to describe Gibson is simpler: he was a catcher who hit like an apocalypse.

In the Negro Leagues, Gibson became an imposing force for powerhouse clubs like the Homestead Grays and the Pittsburgh Crawfords, anchoring lineups that were built to punish pitchers and entertain crowds. Catching, in that era, was already a position of attrition—squatting through games, absorbing foul tips, managing pitchers, controlling the running game. Gibson did all of it while also serving as a middle-of-the-order terror. The Baseball Hall of Fame characterizes him plainly as a dominant two-way presence: a power hitter who also controlled the game behind the plate.

His career exists in the space between recovered statistics and unrecoverable circumstance. Negro Leagues record-keeping was uneven not because the baseball was casual, but because the infrastructure was. League games were only part of the business model; teams made money barnstorming, playing exhibitions, and taking guaranteed payouts wherever they could. That meant box scores were scattered across local papers, sometimes incomplete, sometimes lost. When modern researchers rebuilt databases from surviving records, they did not manufacture greatness; they documented what had been treated as disposable. The result is not a perfect ledger, but it is far more than legend.

When MLB incorporated Negro Leagues statistics into its record books after a multi-year review, Gibson’s greatness didn’t inflate—it clarified. He emerged as the career leader in batting average, and his single-season numbers became record-shifting landmarks. The point is not that Gibson needed MLB’s validation to be great. It’s that MLB’s record book needed Gibson to be honest.

And yet, the tragedy in Gibson’s biography is that his name now sits comfortably atop leaderboards while his life ended early, long before he could enjoy the safety and renown that came to some of his contemporaries. Gibson died in 1947—on the eve of the integration era—never getting the chance that would have made him, in the eyes of white America, “real.” The timing feels cruel because it is cruel: the country built a gate, then opened it just after one of the era’s most extraordinary talents was already gone.

If Gibson represents anything beyond raw ability, it is the way segregation didn’t merely exclude—it distorted the arc of a life. The question that hovers over him is not “How good was he?” but “What did it cost to be that good in that world?”

Satchel Paige, the pitcher as storyteller, scientist, and spectacle

Satchel Paige is baseball’s great character in the precise sense: not a mascot, not a gimmick, but a personality so large it became part of the performance, a pitcher who understood that dominance could be theatrical without being fake. He could sell a crowd and still carve a lineup.

Paige’s resume stretches across the Negro Leagues, barnstorming tours, and, eventually, the majors—arriving there in a way that remains almost absurd: he made his MLB debut at 42, signed by Bill Veeck’s Cleveland Indians, and became the oldest debutant in modern major-league history. That fact is usually delivered as trivia; it should be delivered as indictment. In a sane system, Paige is not a 42-year-old rookie. He is a 22-year-old phenom facing the best hitters in the world while he is still at his physical peak.

The Hall of Fame’s account of Paige’s debut emphasizes the distance he traveled—nearly two decades of barnstorming and Negro Leagues excellence before the American League finally paid him what white baseball had withheld. The Washington Post, writing around MLB’s 2020 recognition of the Negro Leagues as “major,” noted that Paige’s greatness never depended on the announcement; it existed in the grain of memory, in the testimony of people who watched him, and in the longstanding knowledge that the sport had been running a segregated talent embargo.

Paige’s style—hesitations, varied arm angles, late life fastballs that still had bite—invited myth. But the myths often sit on top of a more concrete reality: Paige was a working pitcher in an unstable labor market. He played where the money was, where the booking was, where the crowds would pay to see him. The hustle was not always romantic. It was survival.

Even after he reached MLB, Paige’s career remained a reminder of what had been stolen. Yes, he pitched in the World Series and earned the kind of national spotlight that segregation had denied him. But he did so with an entire prime already spent proving himself in a separate universe. When MLB eventually integrated Negro Leagues stats into the historical record, it wasn’t just Gibson who moved in the books; the story also reframed Paige’s place in pitching history, adding institutional weight to what Black baseball had long known.

Paige’s challenge was never only hitters. It was time. It was the calendar of a life bent by policy—forced to wait, forced to roam, forced to turn mastery into performance because performance was what paid.

Oscar Charleston, the complete player who belongs in any GOAT argument

If you want a single player who collapses the false boundary between Negro Leagues “legend” and baseball “history,” you start with Oscar Charleston. He played center field with a kind of muscular range that made the outfield feel smaller; he hit with power and control; and he managed, too, because Black stars were often asked to do more than star—they were asked to stabilize organizations.

Charleston’s Hall of Fame biography frames him as one of the greatest players in the Negro Leagues: a powerful hitter who could also bunt, a complete offensive presence who could beat you multiple ways. He played for major teams and remained a star across decades of shifting leagues and economic realities.

Charleston’s career also highlights a key truth about the Negro Leagues: these players were not merely playing baseball; they were constantly adapting baseball to the circumstances it was forced into. In white major leagues, a star could settle into a franchise and build continuity. In Black baseball, continuity was always fragile—subject to ownership changes, league collapses, and the financial logic of barnstorming. A player like Charleston had to be great and portable.

The challenge in writing Charleston is that his greatness is sometimes described in superlatives that feel abstract. So consider the skill set: center field defense that requires speed, routes, arm strength, courage at the wall; an offensive profile that includes power, contact, and situational intelligence; leadership in a segregated sport where leadership meant navigating racism on the road and responsibility at home. Charleston did not specialize. He commanded.

He belongs in any argument about the best all-around baseball players of the first half of the twentieth century. The fact that he is not routinely treated that way is not a baseball failure. It is a historical one.

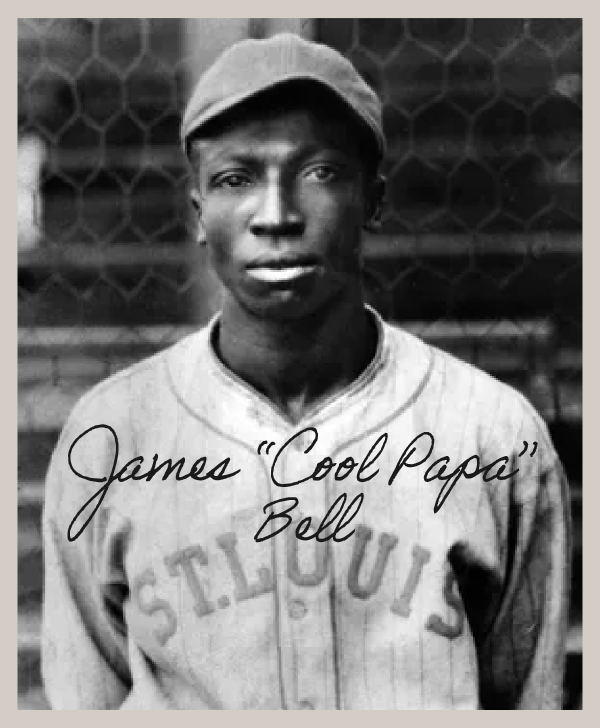

James Cool Papa Bell, speed as liberation and burden

James “Cool Papa” Bell is often introduced through a story about speed—a legend so sharp it feels like a punchline. The details vary, the exaggerations are part of the fun, and the point is always the same: Bell could run.

But speed, for a Black ballplayer in early twentieth-century America, was not merely a tool. It was a kind of freedom—temporary, conditional, hard-earned.

The Hall of Fame describes Bell as a player who confounded opponents with his ability to reach base, a description that is almost understated. Getting on base in that era meant beating gloves, beating throws, beating the assumptions that a smaller player could be bullied. It meant turning contact into chaos. Bell did it for teams like the St. Louis Stars and Pittsburgh Crawfords, moving through lineups as a spark and an engine.

Yet the “speedster” label can flatten him. Bell was not only a runner; he was a baseball intellect in a game where base-stealing requires reading pitchers, studying tendencies, and exploiting fear. The myth says he was fast enough to turn lights off and be in bed before the room got dark. The reality is that he was skilled enough to make professionals feel slow.

Bell’s challenge was that he played in an ecosystem that commodified spectacle. Black baseball needed crowds; crowds needed stars; stars had to deliver something unforgettable. For Bell, that “something” was often speed. It made him famous, but it also risked turning a complete player into a single adjective.

In the record-book era, the temptation is to chase his exact stolen base totals. But to understand Bell, you have to understand how speed functioned in Black baseball: it was strategy, entertainment, and sometimes a quiet protest. If you could not be allowed to hit in the same parks as white stars, you could still outrun everyone in yours.

Buck Leonard, the first baseman who made dynasty feel inevitable

Walter “Buck” Leonard spent the core of his career with the Homestead Grays, part of a sustained run of excellence that made the Grays feel like more than a team—they were a standard. The Hall of Fame calls Leonard one of the best pure hitters in the Negro Leagues and notes his unusually long tenure with one club, as well as his record-setting number of East-West All-Star appearances.

Leonard’s name is often linked with Gibson’s because the two formed a devastating middle of the order. Where Gibson brought explosive force, Leonard brought the kind of left-handed authority that can control a game even without fireworks. He was a first baseman, yes, but in the Negro Leagues the position was never just about defense at the bag; it was about anchoring lineups and stabilizing a roster that might be pulled apart by economics.

The Grays’ run to multiple Negro World Series—and their championships in the early 1940s—underscores Leonard’s significance not just as an individual but as part of a winning infrastructure. That matters because the Negro Leagues are too often told as a story of individual brilliance without the organizational competence that made that brilliance visible. Great teams require planning, scouting, leadership, and consistent execution. Leonard’s career suggests that Black baseball built those systems even when white baseball refused to acknowledge them.

Leonard’s challenge was not proving he could hit. It was living in a country that treated his excellence as unofficial. When he was inducted into the Hall of Fame, the honor finally arrived in the mainstream language of baseball immortality. But the delay is part of the story: Leonard had already lived most of his life by the time the institution said what Black baseball already knew.

Turkey Stearnes, the quiet five-tool star who hit like thunder

Norman “Turkey” Stearnes is sometimes described with a kind of affectionate curiosity—his nickname, his running style, his quiet personality. The Hall of Fame biography notes the lore around his nickname and emphasizes that he was a “five-tool player,” capable in every phase of the game.

But the most important line in Stearnes’s story might be the one attributed to Satchel Paige, who called him one of the greatest hitters and placed him in the same tier as Josh Gibson. In a baseball culture where pitchers rarely offer compliments to hitters, this reads like testimony under oath.

Stearnes played for the Detroit Stars and other clubs, shining in a Midwestern ecosystem where Black baseball was both deeply rooted and perpetually precarious. The Stars’ legacy is now part of a renewed public conversation because MLB’s integration of Negro Leagues statistics has also directed attention back to teams and cities that hosted this parallel major-league world.

Stearnes’s challenge was the classic Negro Leagues bind: to be extraordinary without the guarantee that extraordinary would be preserved. Quiet men are especially vulnerable to erasure because they do not cultivate their own mythology; they trust the game to speak. When the record-keepers are absent, that trust can be punished.

A five-tool player in a segregated sport carries a particular ache. The tool set is designed for the biggest stage. The stage was denied. Stearnes performed anyway.

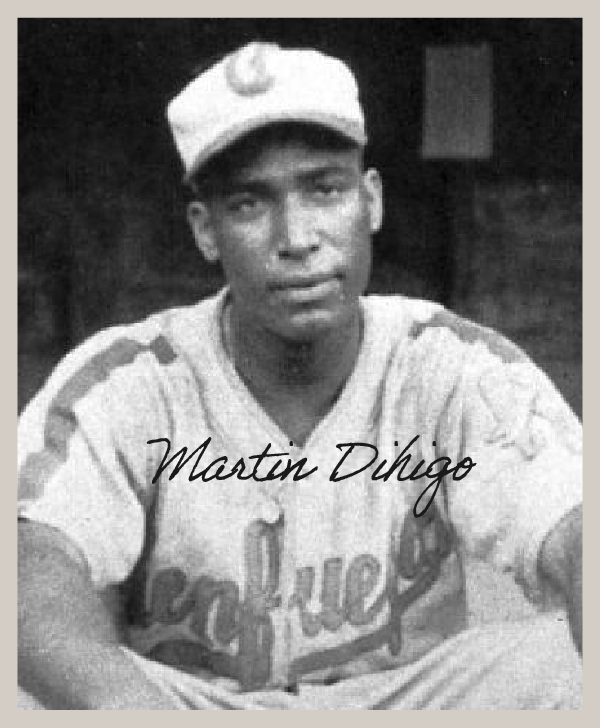

Martín Dihigo, “El Maestro,” and the international Negro Leagues reality

To understand Martín Dihigo is to understand that Negro Leagues greatness was often transnational. The United States did not merely segregate baseball; it pushed Black and Afro-Latino stars into a broader circuit—winter leagues, Caribbean seasons, Latin American professional leagues—where talent could sometimes find different forms of respect and compensation.

The Hall of Fame calls Dihigo “El Maestro,” and the nickname is not decorative. Dihigo’s legend rests on his versatility: he played multiple positions, including on the infield and outfield, and also pitched. In modern baseball, we treat two-way play as novelty; in Dihigo’s era, his ability was closer to an affront to the idea of specialization. He could beat you anywhere.

Dihigo’s career also signals how Black baseball complicates American parochialism about the sport. The Negro Leagues were deeply American in their relationship to Jim Crow, but their labor market was often hemispheric. Players moved to Cuba, Mexico, the Dominican Republic, and elsewhere not simply for adventure but for work and dignity. Dihigo’s biography, as preserved by major baseball institutions, emphasizes both his early U.S. Negro Leagues debut and his larger legend as a player whose grace and excellence traveled.

His challenge was that versatility can be hard to quantify in a culture that loves single-number arguments. What is the WAR of a man who could fill holes on a roster, pitch when needed, and still hit? How do you explain “indispensable” to a record book?

Dihigo makes the case that Negro Leagues greatness is not only about what was denied in the U.S. It is also about what was built beyond it—an Afro-Atlantic baseball world that treated Black skill as valuable even when America refused to.

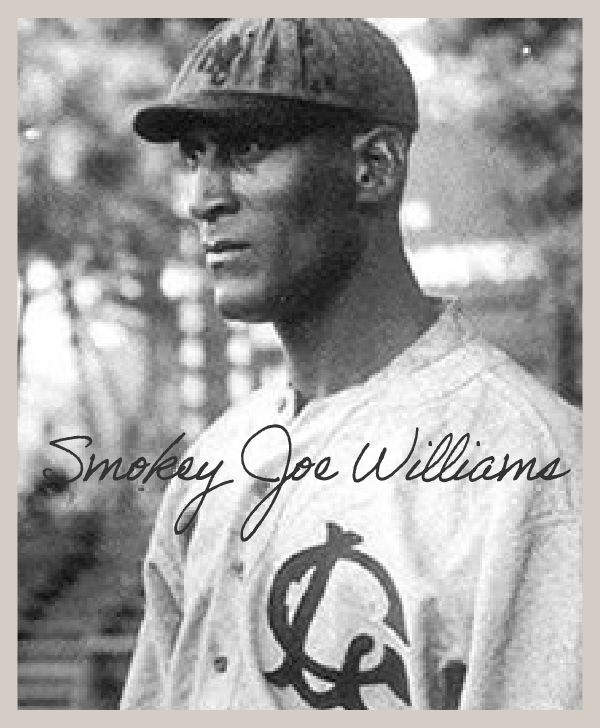

Smokey Joe Williams, the feared pitcher whose era predates the spotlight

If Satchel Paige is the charismatic icon of Negro Leagues pitching, Smokey Joe Williams is the embodiment of its earlier terror: a right-hander known for fastball dominance, control, and longevity. The Hall of Fame describes him as one of the most feared pitchers of the first half of the twentieth century, a drawing card whose talent traveled across teams including the Lincoln Giants and the Homestead Grays.

Williams’s career highlights an important structural fact: Negro Leagues baseball did not begin in 1920, even if the “organized” major Negro Leagues era is commonly anchored there. Black professional baseball existed before the formal league structures that historians often use for statistical boundaries. That means early stars are sometimes doubly disadvantaged—first by segregation, then by the fact that their prime occurred before the most widely documented years.

MLB’s historical pages on Williams emphasize his stature and his extended career, and also note the reputational evidence: in a 1952 poll conducted by the Pittsburgh Courier, he was voted the top pitcher in Negro Leagues history. That kind of peer-community recognition matters because it reflects how Black baseball evaluated itself: not as a consolation prize, but as a competitive ecosystem with its own standards and legends.

Williams’s challenge was that pitching dominance is the hardest thing to preserve without clean records. Hitters leave artifacts—distance, sound, memory. Pitchers leave gaps: games that were never fully documented, barnstorming performances that lived in rumor, matchups against white semi-pro clubs that were not treated as “official.” And yet, the testimony persists: fear is its own statistic.

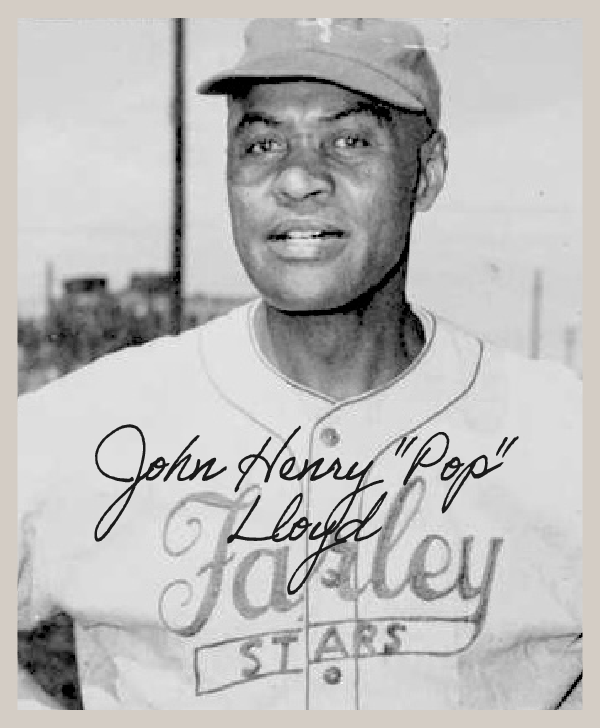

Pop Lloyd, the shortstop as engineer

John Henry “Pop” Lloyd is frequently described in almost architectural terms: “scientific hitter,” finest shortstop, a player who personified athletic quality and character. The Society for American Baseball Research, summarizing the language of his Hall of Fame plaque, captures how he was remembered: an elite shortstop, a precise hitter, a leader who also managed and helped open big stages—including Yankee Stadium—for Negro Leagues baseball events.

Shortstop is the position that reveals whether a player actually understands baseball. It is angles, timing, hands, footwork, arm strength, and decision-making compressed into fractions of seconds. To be an all-time shortstop is to be a kind of engineer. Lloyd’s greatness, by reputation and institutional recognition, sits precisely there.

Lloyd’s career also underscores the intellectual quality of Negro Leagues baseball. The popular imagination sometimes treats the leagues as raw athleticism unconstrained by strategy. In reality, Black baseball was intensely tactical, and its stars often developed an advanced feel for the game because they had to win not only the contest but the crowd. Fans were paying for excellence; excellence required craft.

Lloyd’s challenge was that craft is easy to overlook when the culture is hungry for spectacle. Gibson homers and Paige showmanship travel easily in story form. Lloyd’s genius—precision, positioning, consistency—requires writers and historians to pay attention. Thankfully, many did, and the record now holds him as one of the position’s standard-bearers.

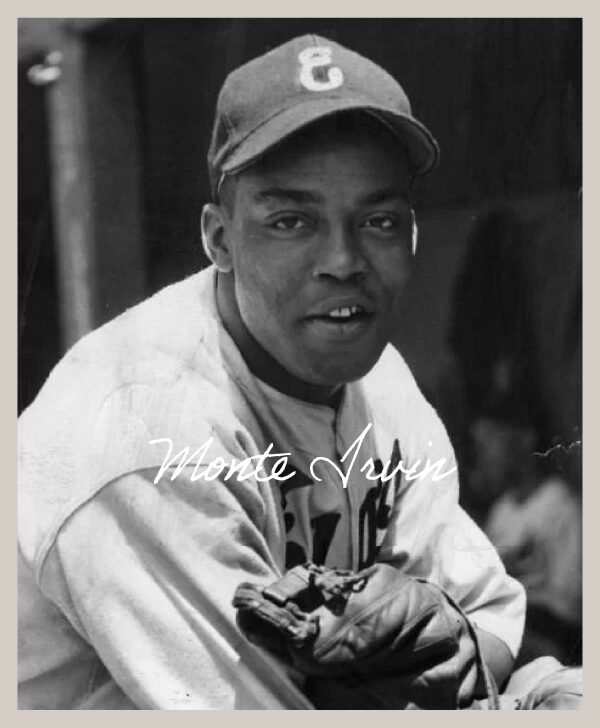

Monte Irvin, the bridge between worlds and the cost of delay

Monte Irvin belongs in Negro Leagues conversations not only because he was a star with the Newark Eagles, but because his life illustrates what integration did and did not fix. He is a bridge figure: brilliant in Black baseball, productive in Major League Baseball, and uniquely positioned to describe the absurdity of a segregated system that pretended to be about “ability.”

The Hall of Fame calls Irvin one of the top all-around athletes of his era and traces his path from the Newark Eagles to the New York Giants and beyond. But the most piercing evidence may be Irvin’s own words, preserved by the Hall of Fame: the disbelief that Black players felt when they beat white competition in exhibitions and still weren’t allowed in the league; the recognition that the difference wasn’t baseball but money and power; the humiliation of discrimination that followed even when a player finally wore a major-league uniform.

Irvin also represents the theft of time in a more literal way. His career was interrupted by military service in World War II, and by the broader delay imposed by MLB’s integration timeline. By the time he became an MLB regular, he was older than a typical star entering his prime. And yet he still performed at a level that made him an essential part of Giants teams that contended, and a veteran presence in a clubhouse that soon included Willie Mays.

Irvin’s challenge is that he is sometimes treated as a supporting character in larger stories—Jackie Robinson’s integration, Mays’s emergence, the Giants’ glory. But he was not a footnote. He was a star whose career demonstrates the full absurdity of segregation: even when the “barrier” broke, it broke late for many of the men who had been best suited to shatter it.

He is also, crucially, evidence that Negro Leagues greatness translated. There was never a question about whether it would. The only question was why it took so long for white baseball to admit what it already knew.

What these ten men shared: Excellence under conditions designed to distort it

The Negro Leagues were an arena of brilliance, but they were also a set of constraints that shaped every career. These players shared obstacles that white major leaguers rarely had to consider in the same way: constant travel with limited lodging options; unpredictable pay; the necessity of playing exhibitions and extra seasons to make a living; and the psychic burden of being asked to prove humanity through performance.

Institutions have begun, belatedly, to name the Negro Leagues as “major” in the official sense. The Guardian framed MLB’s 2020 reclassification as a correction of a “clear error,” and later coverage emphasized how the 2024 statistical incorporation reshaped baseball’s historical understanding. The Atlantic, in reviewing the documentary The League and in subsequent commentary around the record-book changes, has explored the “afterlife” of Negro Leagues baseball—what was lost when the leagues declined, what remains unresolved in public memory, and why the reckoning is as cultural as it is statistical. The Negro Leagues Baseball Museum continues to make the case, through preservation and storytelling, that this history is not a side exhibit but a central American narrative.

And still, it is important not to allow a record-book update to become the end of the conversation. Statistics are a tool; they are not closure. The Negro Leagues story is not only about who led in batting average. It is about why those averages were treated as unofficial in the first place.

That is why these ten players matter as a group. They represent multiple archetypes of greatness—power, finesse, speed, intellect, versatility, endurance—and they demonstrate that Black baseball did not produce one kind of star. It produced every kind. The only thing it could not produce was the structural permission that white baseball hoarded for itself.

The reckoning that baseball still owes

There is a final irony in the current moment. MLB’s incorporation of Negro Leagues statistics is framed, understandably, as an act of honor toward players like Gibson and Paige. But one Atlantic writer argued that the inclusion also flips the moral direction: it is MLB that is honored by being forced—finally—to tell the truth about who belongs in its history.

Because the Negro Leagues were never merely about baseball. They were about the American habit of building separate systems and then pretending the separation was natural. They were about the ability of Black communities to create institutions under pressure—teams, leagues, newspapers, traveling circuits, fan cultures—when exclusion was policy. They were about excellence that refused to wait for permission.

Josh Gibson’s swing, Satchel Paige’s pitch, Oscar Charleston’s complete command, Cool Papa Bell’s acceleration, Buck Leonard’s steadiness, Turkey Stearnes’s quiet power, Martín Dihigo’s boundless utility, Smokey Joe Williams’s menace, Pop Lloyd’s engineering, Monte Irvin’s bridging grace—each is a story of mastery. Together they are a story of a sport that was never whole until it admitted who had been playing it all along.

And if baseball wants the reckoning to be more than ceremonial, it has to keep doing what the Negro Leagues demanded by existing: tell the story in full, invest in preservation, teach the context alongside the highlights, and treat Black baseball not as nostalgia but as infrastructure—one of the most important cultural achievements American segregation inadvertently forced into being.

That, more than any corrected leaderboard, is what these men earned.