KOLUMN Magazine

In that caring—steady, unsentimental, demanding—we learned to fish

In that caring—steady, unsentimental, demanding—we learned to fish

By KOLUMN Magazine

In our Norfolk, Virginia childhood—the 1970s folding into the 1980s like pages turned with a thumb damp from summer sweat—time was not kept only by clocks. It was kept by who was working, who was watching, who was waiting at the curb, who was riding in the front seat because they were grown, and who was riding in the back because they still had learning to do. We lived in an economy of hours: my mother’s long shifts, school bells, dinner plates, streetlights, and the quiet bargains families make when the calendar refuses to cooperate with a paycheck.

My mother was a bank manager full-time and an accountant on the side for small businesses, which meant she carried other people’s numbers all day and then brought more numbers home at night. She was not the kind of woman who romanticized exhaustion, but she understood it as a cost of entry. The job gave us stability; the hours took her away. If childhood is often narrated as a private world of scraped knees and cartoon theme songs, ours had an additional soundtrack: the click of a briefcase latch, the scratch of a pen against ledger paper, the sigh that came from deep in the lungs when she leaned over the kitchen table late and checked one more column.

That’s where the Parkers came in.

Mr. and Mrs. Parker were older than my mother by enough years that they moved through the neighborhood with a kind of earned authority. They were working-class, not by aesthetic but by lived fact: the sort of people who understood the difference between wanting and needing, who could fix things with what was on hand, who treated waste as a moral failure and generosity as a practice. In the language of many Black communities, Mr. Parker was an elder—not merely old, but recognized. He didn’t need a pulpit for people to listen when he spoke. His physical presence helped: he was a large man, broad enough to make a doorway look narrower when he filled it. But it wasn’t just size. It was the calm that sat on him like a well-worn coat.

Mrs. Parker, in contrast, held her authority in motion. She didn’t formally work outside the home, but to say she didn’t work would be to misunderstand what the neighborhood asked of her. She cared for elderly people around her—fresh produce from community gardens, meals, companionship—small acts that were not small at all when you added them up across weeks and months. If Mr. Parker was the elder you measured yourself against, Mrs. Parker was the one who measured whether you were fed, washed, and made right.

They took care of my brother and me when my mother worked late. Some families call that babysitting; in our memory it feels closer to stewardship. It wasn’t just supervision. It was training in what to notice: how to greet adults, how to accept correction without taking it as humiliation, how to act in public so that the public did not act upon you.

And in the spring months—Fridays, specifically—the Parkers’ care came with a ritual that turned an ordinary school week into a story worth retelling for decades.

They took us fishing.

There are childhood experiences that arrive as gifts and others that arrive as assignments. Fishing with the Parkers was both. It was an adventure we looked forward to all week, and it was also work—real work, with dirt under fingernails and the possibility of failure. Some Fridays the fishing meant a small city reservoir. But the nights that stamped themselves into the bright metal of memory happened at the fishing piers in Virginia Beach.

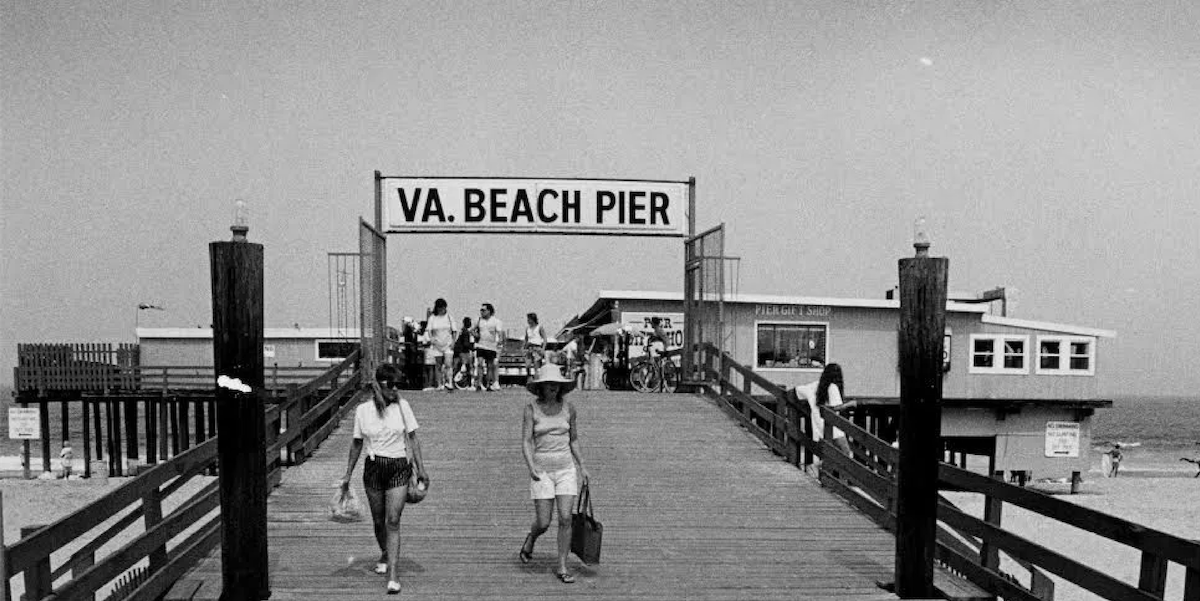

The Virginia Beach Fishing Pier—at the end of 15th Street—has long been a landmark where tourists and locals meet the Atlantic on a platform of planks and faith. Accounts of its history note it first opened in the summer of 1950, built as a place to step beyond the shoreline and look back at the resort strip. In the decades that followed, it became its own small economy: bait, tackle, food, conversation, the occasional spectacle of a surprising catch.

But before it was history to us, it was simply the place the Parkers drove to late on Fridays, after we did the necessary things—worms, dinner, nap, packing—that made the night possible.

The first part of the story begins with a curb

It was late afternoon when the Parkers would pick us up from elementary school—spring sunlight slanting through the bus lane, kids spilling out with book bags and the last of the day’s energy. The Parkers’ car arrived like a signal flare. We’d spot it and feel our bodies lift with anticipation because we knew what kind of Friday it was. Our mother might not be there—she’d be at the bank or headed to a client’s books—but the Parkers were there, and that meant the night belonged to the water.

Mr. Parker’s greeting was never excessive. He didn’t perform affection; he practiced responsibility. He’d check that we were presentable, that we had what we needed, and then we’d get in. It always felt like entering a different jurisdiction: the Parker jurisdiction, where rules were clear and where the adults were not negotiating with children.

We rode to their house with the windows down if it was warm enough. Norfolk air carried the faint industrial tang of a port city, mixed with whatever neighbors were cooking for supper. The Parkers’ place was familiar, and yet on fishing Fridays it transformed. The house was not simply where we waited for our mother. It was where the night assembled itself.

At around 4:30 p.m., as soon as we arrived, my brother and I would walk across the street to a vacant lot to dig for worms. The lot wasn’t scenic. It wasn’t the kind of place you’d photograph for nostalgia. It was dirt, mounds of soil, an unclaimed patch of earth doing what unclaimed earth does: growing weeds, holding secrets, hosting life you didn’t see until you disturbed it.

We carried a coffee can—one of those repurposed objects that working-class households turn into tools. The lid would scrape and pop, and the sound meant readiness. We used whatever we had—sticks, hands, sometimes a small shovel if it was available—to turn the soil. The worms were there, deep enough to feel like discovery but close enough to make the hunt successful. The lot, we learned, was filled with them, as many as we could store.

Digging worms is a kind of apprenticeship in itself. It teaches you that bait doesn’t appear because you want it. It teaches you to touch things that make you briefly uncomfortable because the goal requires it. It teaches you to be practical about life: you are taking living creatures to tempt other living creatures, and you do it without apology because you intend to eat what you catch.

When we returned with the coffee can heavy with its writhing contents, the Parkers didn’t praise us like we’d done something extraordinary. They simply accepted that we’d completed the first task. That was the Parker way: don’t inflate effort into ego; make effort normal.

Around 5:30 p.m., Mrs. Parker would tell us to “Wash Up.” The instruction came with a tone that made it less a suggestion than a resetting of the world. Wash up meant more than soap and water. It meant you were transitioning from outside boyhood—dirt, worms, vacancy-lot freedom—into inside boyhood—manners, dinner, preparation.

Dinner at 6:30 p.m. was another quiet ritual. The meal grounded us. It was the last full stop before the long sentence of the night. The food was simple and serious, and the table was where you learned to listen more than you spoke. In many homes, dinner is family time; in the Parkers’ home, dinner was also training time. You learned to say “yes ma’am,” “no sir,” to ask for what you needed without acting entitled to it, to chew without rushing. In the background was the unspoken understanding that the night ahead would ask for stamina, and stamina is built on routine as much as excitement.

After dinner, we took a nap for a few hours. This was not indulgence; it was strategy. Children resist sleep when they feel something good waiting for them. But the Parkers had no interest in our resistance. They knew the pier wasn’t a place where you could fall apart at 1 a.m. because you refused to rest at 7. So we slept, the house quieting, the day folding down.

When we woke, the world had changed. It was 9:30 p.m., and the Parkers were up and packing the car. The trunk and back seat filled with the practical artifacts of a long night: tackle, fish and crab bait, sandwich bread, fried chicken wrapped in foil, water. Each item had a purpose, and the purpose was survival—if not survival in the life-or-death sense, then in the endurance sense. You don’t fish overnight without fuel.

Packing was a choreography. Mr. Parker handled the heavy gear with a steadiness that made everything look easy. Mrs. Parker checked the food like a quartermaster. My brother and I hovered, pretending we were in the way less than we were, trying to look useful. In the air was excitement—ours, certainly, but also theirs, though the Parkers wore excitement differently. Adults of their generation rarely announced joy; they embedded it in doing.

By 10:30 p.m. the pier appeared, and the story stepped into a different scale.

To two boys from Norfolk, the Virginia Beach Fishing Pier seemed like a small city: long, bright in places, busy with conversation and foot traffic, with small shops and food and gear and people committed to catching as much as they could. That sense of it as a city wasn’t only metaphor. Piers are built environments, and the built environment shapes behavior. On land, adults tell children to be careful; on a pier, caution becomes physical. The edge is right there. The water is dark. The boards can be slick. And yet the place hums with life—families, solo anglers, groups of men who look like they’ve been doing this for decades, teenagers trying to impress one another by casting far.

The pier’s history is often told through dates—its 1950 opening, its place as a centerpiece of the resort strip, the businesses that have operated on it. But on that night, to us, it was history in motion: a living archive of coastal ritual. You could smell bait and salt, fried food and the sharp clean scent that rises off the ocean when the wind shifts.

We stepped onto the planks and felt the slight give beneath our shoes. A pier teaches you immediately that the ground is not always solid. The boards vibrate faintly with footsteps, a collective pulse. We carried coolers that seemed too big for our arms and rods that felt like extensions of responsibility.

From 11:00 p.m. to 7:00 a.m., the night became routine, and routine became proof.

There’s a version of fishing you see in magazines, where the angler is alone in serene daylight, reflecting on life. Our fishing was communal and nocturnal. It was loud with human presence and quiet with concentration. It wasn’t about philosophical solitude. It was about competence.

The routine asked us to demonstrate, again and again, that we weren’t just kids brought along for charm. We had jobs. We had expectations. We were learning the full chain of tasks that made fishing possible: pointing out which rods bent suddenly toward the ocean when fish taunted, changing lines, picking the proper sinker, baiting each hook, reeling in, casting, pulling up and emptying crab cages.

Each action had its own lesson

Pointing out a bending rod taught vigilance. You weren’t allowed to drift into daydreams. The ocean didn’t care about your attention span. Fish strike when they strike. If you missed it, that was on you. You learned to scan the line angles like a guard scanning a fence line.

Changing lines taught humility. Sometimes the line snapped. Sometimes it tangled. Sometimes you made a mistake. The point was not to blame the equipment; the point was to fix it, quickly, without drama.

Choosing a sinker taught judgment. Too heavy and you lost feel; too light and you lost position. This is what elders teach without naming it: most choices in life are not about right or wrong but about fit.

Baiting hooks taught steadiness. The worm squirmed, the hook was sharp, your fingers were small. You had to hold the bait firmly enough to thread it but gently enough not to destroy it. There was an ethical lesson hidden in the practical one: don’t be cruel because you’re in charge of something smaller than you.

Casting taught confidence measured by caution. You had to swing the rod and release at the right moment, but you also had to look behind you to make sure you weren’t about to hook someone. The pier demanded awareness of others.

And crabbing—pulling up and emptying cages—taught that the ocean’s gifts are never clean. Crabs fight. They pinch. They cling. The basket comes up heavy and alive, and you have to manage it without panic. The Parkers’ equipment, the kind used for crabbing from a pier, belonged to a broader coastal tradition regulated to protect the blue crab fishery—gear rules, size limits, and other constraints that have evolved over time. But in our memory the regulation was simpler: don’t get careless with your hands, and don’t waste what you catch.

What made the night feel like a rite of passage wasn’t only the work; it was the Parkers’ quiet evaluation. They didn’t clap. They didn’t narrate our growth in sentimental language. They watched. And when we did something right, we got a subtle smile and nod. That was the reward: recognition without spectacle.

Other people noticed us too. On a pier, strangers become witnesses. Someone would see my brother manage a line change without snarling it. Someone would see me call out a rod bend fast enough to prevent a missed catch. Compliments would come—directed at the Parkers, really, as much as at us. The Parkers would receive those compliments with pride. Not pride that puffed them up, but pride that confirmed their investment was paying off.

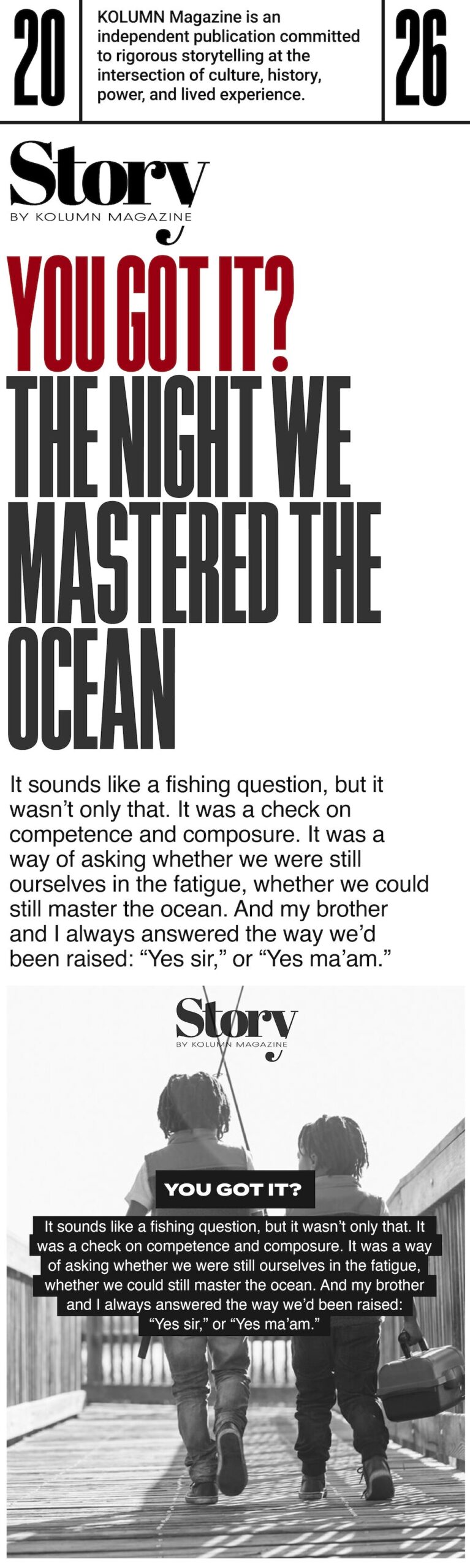

Every so often they’d ask, “You got it?” It sounds like a fishing question, but it wasn’t only that. It was a check on competence and composure. It was a way of asking whether we were still ourselves in the fatigue, whether we could handle what we’d agreed to. And my brother and I always answered the way we’d been trained: “Yes sir,” or “Yes ma’am.”

Hope was the fuel we started with

At the beginning of the evening, we carried the fantasy of abundance: coolers filled with trout and spot fish by morning; crab baskets heavy enough to justify their own cooler. Some of that hope was childish exaggeration. Some of it was based on real possibility. Piers along the Virginia coast are known for a rotating cast of species—spot, croaker, Spanish mackerel, and others depending on season and conditions—and the very act of fishing from a pier is a way of meeting that variety without owning a boat.

But hope doesn’t guarantee results, and fishing teaches that better than most childhood hobbies. You can do everything right and still come up light. The ocean is not a vending machine. It’s a system. It gives and withholds on its own terms.

Around 2:00 a.m., our bodies would finally settle into the quiet part of the night. This was the hour when the pier thinned a little, when conversation softened, when you could hear more clearly the steady hush of water moving beneath the boards. We would sit with homemade sandwiches—built from the bread the Parkers packed, maybe supplemented by the foil-wrapped fried chicken that had cooled into a different kind of delicious.

We’d open the coolers and peek at our progress, smiling. There is a specific pleasure in checking a cooler at night: the flash of fish scales under a weak light, the cold air spilling out, the sense that your effort has become inventory. It’s part triumph, part reassurance. You haven’t been awake for nothing.

And then you go back to work

The hours between 2 a.m. and dawn were the true test. This is the part people don’t romanticize because it’s too honest. Your hands get stiff from handling wet line. Your eyes burn from staring into darkness. Your stomach doesn’t know whether it’s hungry or tired. The pier’s lights carve the night into zones: bright where people cluster, dim where solitude gathers.

Mr. Parker moved through those hours with the same steady pace he’d had at 10:30 p.m. Mrs. Parker, too, was awake and attentive, not as a passenger but as a participant. Their endurance wasn’t performative. It was practiced—grown from years in which you did what had to be done regardless of what you felt.

In that way, fishing with them was not separate from the rest of our lives. It echoed the larger world we were growing up in, a world where Black families—especially working families—often relied on extended networks of care, neighborly arrangements, elders who stepped in when the formal economy extracted too much time from parents. The Parkers’ care for us fit within that ecology: informal but dependable, personal but structured.

Norfolk in the 1970s and 1980s was not only a backdrop of childhood play; it was also a city shaped by policy decisions and development pressures that landed hardest in Black neighborhoods. Public history accounts describe how predominantly Black areas like East Ghent were cleared in the late 1960s and early 1970s through redevelopment and eminent domain, displacing residents and remaking the landscape. We were children, not urban historians, but you could feel—without having language for it—that the ground under a community could shift. In a world like that, elders mattered. Stable homes mattered. Routines that you could count on mattered.

On the pier, that stability took the form of small commands and repeated checks: tie this, watch that rod, don’t run, keep your knife closed, wash your hands before you eat again, don’t waste bait, pay attention.

Fishing is often described as patience. But what we learned was closer to discipline.

As the night moved toward morning, the ocean’s darkness began to thin at the edges. You could sense dawn before you could see it. The air changed first—cooler, sometimes wetter. The sky shifted from black to a deep bruised blue, then to something that promised color.

By the time we approached 6:00 a.m., the end was in sight. Not the end of fishing as an idea, but the end of this particular night’s campaign. And endings have their own ritual: gather the gear, collapse the small city you built around your spot on the pier, pack up what you caught and what you didn’t use, make sure nothing gets left behind.

Leaving is work too

We gathered rods and tackle, bait containers and the remains of dinner, towels damp with saltwater. The coolers that had felt ambitious at 10:30 p.m. now felt heavy with proof. Even when the catch wasn’t as full as our first-hour fantasies, it was still weight earned. The walk back to the car was long, and the coolers trailed behind us, pulled like reluctant luggage.

The pier, in daylight’s first reveal, looked less like a city and more like what it was: a structure stretching into the Atlantic, a man-made extension for human wanting. But the feeling of it—the community of strangers, the shared goal, the quiet competitiveness, the mutual respect for anyone who could handle the work—lingered.

We always promised ourselves we’d stay awake during the drive home. Kids say that the way they say they’ll remember to do homework over the weekend. The promise is sincere at the moment of making it. But exhaustion is persuasive. The car’s motion, the warmth, the relief of sitting still after hours on your feet—those things conspire.

We drifted away

Sleep in a moving car is a strange kind of travel. You leave one world and wake in another without experiencing the miles in between. When we woke, we were arriving back at the Parkers’ place. The night had folded itself into morning. The gear was still in the car. The coolers were still heavy. The ocean was now something behind us.

And there, in that moment—waking up not at home but at the Parkers’, with the taste of salt still faint in the mouth and the ache of staying awake still in the eyes—was the quiet truth of what they had given us.

They had given us more than fishing.

They had given us a model of care that was rigorous, not indulgent. They had given us a way of understanding work as something you could do with pride rather than resentment. They had shown us that masculinity—if that’s what the world insisted we were growing into—could be practiced as responsibility, attentiveness, and respect rather than loudness. They had shown us that joy could be built, intentionally, out of ordinary materials: a coffee can, a vacant lot, a foil-wrapped bundle of chicken, a pier that first opened decades before we were born, and an overnight commitment to see something through to the end.

A childhood memory like this can be told as a sweet story—two boys fishing with a kindly older couple. But that would make it smaller than it was. The Parkers’ Fridays were a structure around our lives at a time when our mother’s work demanded structure from everyone. They were a bridge between childhood and whatever came next. They were a way of teaching us to hold steady through the long middle hours of anything—whether that anything was a fishing night or a life.

In the years since, I have met people who speak of fishing as escape, as retreat, as a private conversation with nature. I understand that version. But our fishing was a public education. It was a classroom where the curriculum was competence and the grading scale was respect.

The ocean, after all, doesn’t care who you are. The pier doesn’t care how old you are. The hook doesn’t care if your hands are small. The night doesn’t care if you’re sleepy.

The Parkers cared

They cared enough to pick us up from school. Enough to trust us with sharp tools and real responsibility. Enough to ask, again and again, “You got it?” and to accept our “Yes sir” as a promise we were expected to keep.

And in that caring—steady, unsentimental, demanding—we learned to fish. We also learned how to be held by a community, how to hold ourselves, and how to walk, cooler in hand, toward a car at dawn knowing that whatever was inside the cooler was only part of what we were bringing home.