KOLUMN Magazine

The drape is not simply “free”; it is a constructed freedom, engineered by a painter who understood both the seductions and the limitations of the frame.

The drape is not simply “free”; it is a constructed freedom, engineered by a painter who understood both the seductions and the limitations of the frame.

By KOLUMN Magazine

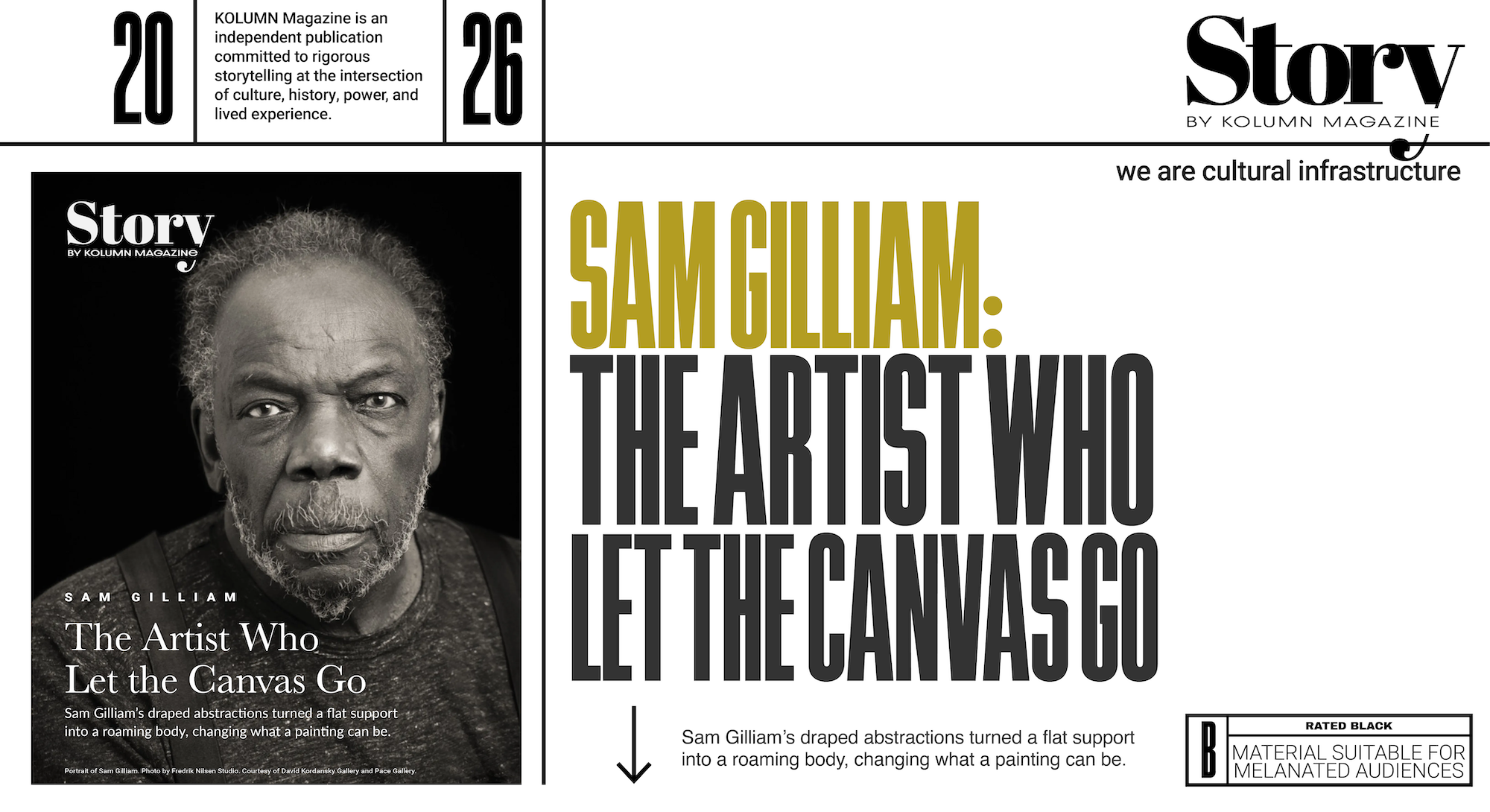

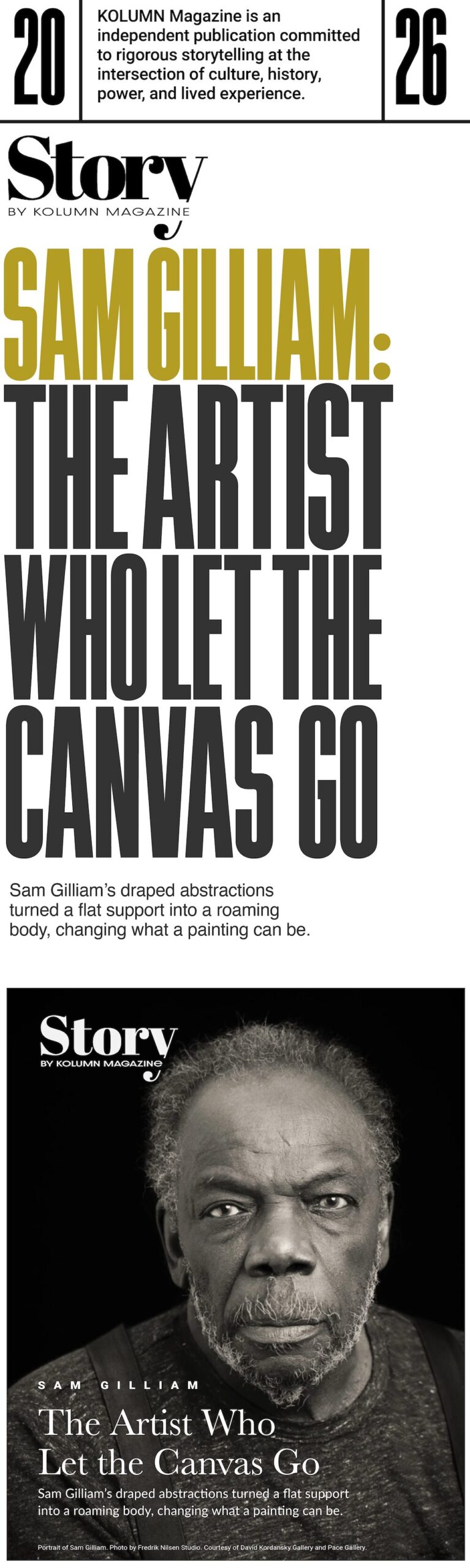

The first thing many people remember about a Sam Gilliam painting is not what it depicts, but what it does: it hangs, it sags, it billows, it spills into the viewer’s space. It refuses the polite posture of framed modernism. It behaves less like a window and more like an event—part curtain, part banner, part weather front. When Gilliam died in Washington, D.C., on June 25, 2022, at 88, obituaries reached quickly for the same verb: he “liberated” the canvas.

That word can sound like a tidy museum label, a slogan made safe by repetition. But “liberation” is only the surface story. Underneath is a longer, thornier narrative: a Black artist coming of age in the middle of 20th-century American abstraction—an arena that often proclaimed itself universal while practicing a narrower, whiter sense of who could stand for universality; a painter in Washington, not New York, making ambitious work at a distance from the art market’s loudest corridors; an innovator whose most famous breakthrough—the draped canvas—was easy to fetishize as a signature look, even as Gilliam kept trying to outrun it.

His career reads, in retrospect, like an argument conducted in color, fabric, and risk. For six decades, Gilliam tested how far a painting could stretch—literally, materially, architecturally—before it became something else. And he tested, too, how a Black artist could insist on abstraction without being conscripted into anyone else’s storyline about what Black art “should” do. Those pressures—critical, political, commercial—did not disappear as his acclaim grew. They simply changed shape.

Gilliam’s story matters now not only because his drapes are spectacular, or because the market eventually chased him, or because museums finally installed him as a pillar rather than an outlier. It matters because his work makes a stubborn, exhilarating claim: that form itself can be a kind of autobiography, and that the freedom to experiment—especially for an artist told, implicitly or explicitly, to stay in a prescribed lane—is never merely formal. It is social, historical, and hard-won.

A childhood between geographies, and an early education in looking

Sam Gilliam was born on November 30, 1933, in Tupelo, Mississippi, and was raised largely in Louisville, Kentucky—two places where the architecture of segregation shaped daily life and where the idea of a Black artist, let alone a Black abstract painter in the postwar sense, did not come pre-installed as an obvious future.

Louisville mattered because it offered a hinge between South and Midwest, between old racial hierarchies and newer industrial realities; it also offered, for Gilliam, an early encounter with institutions that could teach technique. He earned a B.F.A. at the University of Louisville, was drafted into the U.S. Army, and after his discharge returned to complete a master’s degree.

Those biographical milestones can read like a standard mid-century artist résumé: school, service, school again. But in Gilliam’s case, the arc signals something else: discipline and stubborn preparation in a world that did not guarantee him access to the broader art conversation. Abstraction, in the 1950s and early 1960s, was dominated by stories told in New York—by critics, by galleries, by the mythology of heroic individualism. The rhetoric of the era suggested that painting’s problems were purely internal: surface, color, gesture, composition. Yet the art world’s gatekeeping was profoundly external, entangled with race and geography, with who got visibility and who did not.

Gilliam entered that world from a slight remove: not just as a Black artist, but as one whose adult career would be built in Washington, D.C.—a city with its own cultural ecosystems, its own patrons, its own institutions, and its own fraught politics of representation. That remove would become both obstacle and advantage. It could marginalize him from the commercial center; it could also, paradoxically, give him room to invent.

Washington, D.C.: a city of institutions—and a laboratory for reinvention

Gilliam moved to Washington in the early 1960s. The Washington Post would later describe him as a “Washington artist” who helped redefine abstract painting, with a career marked by “restless experimentation.”

In Washington, he taught—work that paid bills, but also placed him inside a public-facing civic structure, in a city where government, policy, and culture constantly rubbed against one another. That proximity to institutions mattered. Washington is not only a city of museums; it is a city of decision-making, of rules and protocols, of official frames. Gilliam’s most famous gesture—getting painting “off the wall,” shaking it loose from its traditional support—can be read as a formal rebellion. It can also be read as an artist’s intuition about where he lived: in a capital thick with frames.

By the mid-1960s, Gilliam’s work became associated with the Washington Color School, a loosely connected group of painters invested in color as structure, in staining and pouring techniques, in the optical and emotional impact of large fields. The Smithsonian American Art Museum describes him as an “innovative color field painter” who advanced ideas linked to that scene.

To say “Color School” can make the work sound like an orderly movement. Gilliam was never orderly. Color, for him, was not just a retinal experience; it was a physical material—something that soaked into fabric, pooled, dried, cracked, clung, and could be forced to collaborate with gravity. In Gilliam’s hands, the Color School’s interest in pure hue became a platform for improvisation.

The drape: A breakthrough that changed the terms of painting

The draped canvases—often called “Drape” paintings—arrived in the late 1960s and quickly became Gilliam’s most influential invention. Tate notes that he became best known for these works, first developed in the late ’60s, in which the canvas is freed from a stretcher and treated like fabric.

The Metropolitan Museum of Art, discussing a major example from 1970, describes how Gilliam “liberat[ed] the canvas from its stretcher,” pushing a painted support into three-dimensional space; it also places the origin of the drape series in 1968, when the works began to draw acclaim.

It’s difficult now to recapture how radical this would have felt in that moment. Postwar painting—whether Abstract Expressionist or Color Field—was still largely tethered to the rectangle as a kind of faith. Even artists who attacked the canvas with gestural bravado still tended to accept the basic doctrine that painting belonged on a wall, stretched and bounded. Gilliam’s drapes didn’t just tweak that doctrine. They treated it as optional.

The drapes also changed the viewer’s body. You don’t look at them from a single correct distance. You navigate them. You notice how light catches a fold, how pigment thickens at a seam, how the work’s “composition” alters when the fabric slackens or tightens. The painting becomes, in effect, a choreography set by gravity and hanging decisions. It is the same work and not the same work each time it is installed.

Gilliam himself resisted the simplistic interpretation that he had turned painting into sculpture. The Madison Museum of Contemporary Art, in a teaching resource on his work, quotes him saying: “when I did the drape paintings, I wasn’t making sculpture, I was reacting against painting.”

That distinction is not pedantic. It’s philosophical. Gilliam wasn’t seeking a new category for its own sake; he was pressuring painting from inside, forcing it to admit what it had been hiding: that it is always already an object, always already subject to space and context, even when it pretends to be purely optical.

The Corcoran moment, and the scale of ambition

In Washington, Gilliam’s drapes found an institutional stage large enough for their theatricality. The Washington Post obituary credits a 1969 exhibition at the Corcoran Gallery of Art with catapulting him into national acclaim.

This is part of Gilliam’s particular story: that his breakthrough was not only a studio innovation but an architectural one. Drapes needed ceilings, atriums, stairwells—real space that could make the paintings feel like they were colonizing the room rather than decorating it. When the work succeeds, you don’t feel the institution swallowing the art; you feel the art temporarily rewriting the institution’s rules.

This ambition—scale, saturation, risk—also complicates an easy reading of Gilliam as merely a “beautiful” painter. Beauty is present, yes: the sensuousness of stain and fold, the surprising harmonies of color. But there is also assertion. In a period when Black artists were often expected to declare their politics through figuration or explicit iconography, Gilliam declared—through material and scale—that abstraction itself could be a site of Black presence, and that it could occupy monumental space without apology.

Venice, 1972: International recognition and a contested canon

In 1972, Gilliam represented the United States at the Venice Biennale—an event that sits, in the international art world, as a kind of recurring audit of who counts. The National Gallery of Art states that he became the first African American artist to represent the United States at the Venice Biennale that year.

Pace Gallery, which represented Gilliam late in his career, adds institutional detail, noting that he participated as part of a group presentation organized by curator Walter Hopps.

This moment is often presented as a triumphal milestone, and it was. But it also reveals the uneasy arithmetic of recognition. Being “first” does not guarantee being centered afterward. Many artists can testify to that: the first to break a barrier, then the one the canon forgets to keep making room for. Gilliam’s career would include periods of high visibility and periods when the broader market’s attention drifted elsewhere. The Washington Post, looking back on his life, emphasizes that he returned to the drape format throughout his career but remained restlessly experimental across media and construction.

The question, then, is not simply why Gilliam broke through. It is why the art world required, later, a kind of rediscovery.

Formalism, race, and the demand to “mean” in public

Gilliam’s art exists in the long shadow of modernist formalism—the idea that painting’s meaning is embedded in its formal properties, not in narrative or biography. That tradition promised a kind of purity; it also provided a convenient alibi for institutions that wanted to present art as above politics. But for a Black artist in America, “above politics” is rarely a neutral zone. It can become a trap: either your work is read as formal and therefore somehow racially unmarked (an illusion), or it is demanded to perform racial legibility in ways that satisfy curatorial expectations.

A 2020 essay in The New Yorker frames Gilliam as a complicated figure within formalist discourse—an artist influenced by that lineage but also one who exceeded and disrupted it, producing work that fused chance, control, and sculptural presence.

The tension is productive. Gilliam’s work can be approached through color relationships, through edge and stain, through composition in space. It can also be approached as a record of a Black artist insisting on the right to complexity—refusing to be reduced either to a token of “diversity” or to a spokesman obligated to translate his identity into didactic imagery.

This is not to claim Gilliam was apolitical. It is to claim that his politics were embedded in his method: in his refusal to let the art world dictate the acceptable forms of Black expression, and in his insistence that freedom—formal freedom—was itself a meaningful stake.

The work beyond the drape: Cuts, collages, and structures

One reason Gilliam can’t be contained by the drape is that he kept building other vocabularies. The Smithsonian American Art Museum notes that in the late 1970s he began cutting and rearranging geometric shapes from thickly painted canvases, expanding his experiments in color and improvisation.

These later strategies—cutting, patchworking, assembling—can be read as a continuation of the drape’s core idea: that a painting is not obligated to remain intact as a single, stretched surface. Gilliam treated paintings as material with afterlives. A finished canvas could become raw material for a new construction. In this, he anticipated later conversations about reuse, fragmentation, and process—ideas that would be central to many contemporary practices.

Artforum, in a feature on Gilliam’s work, describes pieces that resemble puzzle-like collages, made from cut-up fragments of earlier paintings assembled in a patchwork manner.

Patchwork is a word that carries cultural weight in the United States, especially in relation to Black American craft traditions and the broader history of quilting. It would be simplistic to force Gilliam’s abstractions into a single lineage. But it is also impossible to ignore the resonance: his work repeatedly returns to joining, layering, stitching—literal or implied—turning modernist painting into something closer to textile intelligence.

Museums, collections, and the slow process of institutional acceptance

Over time, Gilliam’s work entered major collections and institutions. The Museum of Modern Art lists multiple exhibitions and holdings, including a 1971 “Projects” presentation and later collection displays, while describing his signature unstretched works as paintings that can be draped, slung, or pinned.

The Met, in its description of Carousel State, emphasizes how Gilliam’s drapes straddle wall and three-dimensional space, showing how deeply his work challenged the assumptions of a “traditional painting support.”

But institutional acceptance is rarely a single event. It is a series of decisions—what gets shown, how often, in what context, next to whom. That context matters. A recent essay in The Atlantic mentions Gilliam’s enormous draped canvas Relative installed at the National Gallery of Art near Helen Frankenthaler’s Mountains and Sea—a placement that signals an argument about lineage and importance.

Placement is curatorial language. It is how museums speak in public without always saying explicitly what they mean. Putting Gilliam in dialogue with Frankenthaler—another pivotal figure in stain painting—suggests that Gilliam is not merely a derivative participant in Color Field history, but a central contributor whose innovations belong in the core narrative of American postwar art.

The late-career reappraisal—and what it revealed about the market

By the 2010s, Gilliam’s reputation experienced a pronounced resurgence: major gallery representation, increased critical attention, and rising prices. Part of this was overdue recognition; part was the art world’s broader reckoning with how it had sidelined artists of color. A 2020 New Yorker piece points directly to how racial bias and art-world trends shaped Gilliam’s uneven commercial recognition in New York, even as his innovations were undeniable.

This reappraisal also reframed the drape. Seen through a contemporary lens, Gilliam’s willingness to let the painting become environmental—responsive to architecture, activated by installation—looks prophetic. Many younger artists, working across painting, textile, and sculpture, operate in a space Gilliam helped open.

And yet there is a cautionary note here. “Rediscovery” can become a flattering story the art world tells about itself, as if the problem was simply a temporary oversight rather than structural exclusion. Gilliam’s career suggests something more bracing: that innovation does not guarantee centrality, and that the canon is not an objective record of greatness but a negotiated space where power and taste intersect.

Full Circle: the late work, and a final return to Washington

In 2022, the Hirshhorn Museum mounted Sam Gilliam: Full Circle, pairing his landmark 1977 painting Rail with a suite of circular works made in 2021—tondos that echoed the Hirshhorn’s own architecture and asked viewers to look closely rather than be overwhelmed by scale.

The exhibition reads, in hindsight, like a coda that refuses sentimentality. The title could have signaled a retrospective mood, a closing of the loop. Instead, it signaled continued experimentation—new formats, new surfaces, a late-career insistence on not repeating oneself.

A review in The Brooklyn Rail notes that the show opened May 25, 2022—exactly a month before Gilliam’s death—and would become his last institutional solo exhibition.

There is something starkly fitting about that timeline. Gilliam’s career was never about arriving at a final style and polishing it into legacy. It was about motion—color in motion, fabric in motion, a practice that kept changing. Even at the end, he was still altering the terms.

The civic artist—and the local importance of being “from” a place

Gilliam is often described as a Washington artist, and not merely because he lived there. He became woven into the city’s cultural identity, a figure of pride and proof. In a town dominated by federal narratives, he offered a different kind of monument: not bronze generals, but color that insisted on joy, complexity, and ambiguity.

That civic presence has a particular resonance for Black Washington, a community that has long wrestled with displacement, political manipulation, and the symbolic uses of Black culture by institutions eager to appear inclusive while participating in exclusionary power. Gilliam’s art did not solve those contradictions. But it offered a model of durability: a Black artist building a life and practice in the capital, not as an adjunct to the city’s official story but as a maker of a parallel one.

This is part of what makes his career so instructive for younger artists who choose to build their lives outside the presumed centers. Gilliam’s Washington was not a compromise; it was a studio at city scale.

Challenges that weren’t purely artistic

The “challenges” in Gilliam’s life cannot be reduced to a single obstacle. Some were structural: racism in institutions, market neglect, the frequent under-documentation of Black artistic networks. Some were interpretive: the pressure to have his work “mean” something legible to viewers who were suspicious of Black abstraction. Some were internal to the practice: how to avoid becoming trapped by the success of the drape, how to keep painting alive as a problem worth solving, rather than a brand worth repeating.

The Washington Post, in its obituary, emphasizes that even though Gilliam was most identified with drape paintings, he continually explored other forms—collage, hinged panels, and three-dimensional construction.

That restlessness can be framed as personality. It can also be framed as strategy: a refusal to be made predictable, a refusal to let the art world domesticate his invention.

Legacy as an institution: The Sam Gilliam Award

After his death, Gilliam’s legacy took on a formal philanthropic structure. In 2023, Dia Art Foundation established the Sam Gilliam Award—an annual prize of $75,000 intended to be transformative for an artist working in any medium, anywhere in the world. Dia notes that the first recipient, Ibrahim Mahama, was announced in March 2024.

It is difficult to imagine a more Gilliam-like form of legacy than one that funds future experimentation. The award does not insist that artists make drapes, or stains, or Color Field homages. It insists only on significance and possibility. It turns Gilliam’s own career—marked by risk and reinvention—into a continuing platform.

What the drapes teach us now

To stand before a Gilliam drape is to confront a paradox: the work feels exuberant and weightless, but it is built on control, labor, and decisions that had to be made against the grain of convention. The drape is not simply “free”; it is a constructed freedom, engineered by a painter who understood both the seductions and the limitations of the frame.

That is why Gilliam’s art continues to matter in the present tense. His work is frequently described as blurring painting and sculpture. That’s true, but incomplete. What it really blurs is a set of inherited assumptions: that abstraction is detached from identity; that innovation is rewarded automatically; that the canon is a neutral ledger; that a painting’s support is merely a support.

Gilliam’s answer—again and again—was to make the support speak. To make fabric carry history. To make color occupy space like a body. To make the wall insufficient.

And perhaps most importantly, to keep moving—through trends, through neglect, through acclaim—without surrendering the right to experiment.